This study examines gender differences in the impact of low-stakes test penalties on academic performance for a first-year undergraduate applied economics course at a public university in Spain using a quasi-experimental design. The study explores how the presence or absence of these penalties for incorrect answers influences students’ grades and whether this impact differs by gender. Statistical analyses include descriptive statistics, permutation tests, bootstrap simulations and linear regression models with interaction terms to explore the complex relationships between test penalties, gender ratios and academic outcomes. The results reveal that removing penalties for incorrect answers increases students’ overall grades significantly and female students benefit relatively more from non-penalising environments. Furthermore, the interaction between the penalty level and the proportion of female students in the class shows that increased penalties affect their grades disproportionately, indicating a gender-specific sensitivity to risk. We also demonstrate that while the presence of female students has a positive influence on overall grades, the combined effect of high penalties and a higher proportion of female students results in diminished performance, underscoring the impact of assessment strategies on gender disparities in academic outcomes. These conclusions are based on simulated classroom configurations derived from resampled individual-level data. The observed interaction patterns indicate differentiated adaptive responses to institutional stressors.

The commitments of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 4 and 5 to eliminate gender disparities in education have intensified interest in understanding the factors that influence differential academic performance between men and women (OECD, 2023). Although significant progress has been made, gaps persist in various subject areas and educational levels, often attributed to sociocultural factors, expectations and learning styles (Chang, 2011; Delaney & Devereux, 2022). A key area of debate is the design of assessment systems and their non-gender-neutral impact. This study investigates the impact of assessment systems that penalise incorrect answers on the gender gap in academic performance in the context of continuous, low-stakes assessment in higher education.

The academic literature has offered divergent perspectives on this concern. First, some research has suggested that penalties for errors on multiple-choice tests do not necessarily harm female students and may even benefit them, since such formats favour better-prepared students and women are often overrepresented in this group (Funk & Perrone, 2016; Akyol et al., 2022). In contrast, a considerable body of research has argued that women, who tend to exhibit greater risk aversion, are more likely to skip questions in penalty settings, thereby disadvantaging their final grades, particularly in high-stakes assessments, where outcomes significantly impact students’ academic progression, admission to programmes or career prospects (Pekkarinen, 2015; Espinosa & Gardeazabal, 2020; Iriberri & Rey-Biel, 2021). This behaviour has been linked not only to risk aversion (Baldiga, 2014) but also to loss aversion (Karle et al., 2022) and psychological factors such as pressure response and anxiety (Shurchkov, 2012; Núñez-Peña et al., 2016).

Our research contributes to this debate by focusing on low-stakes assessments that are crucial for providing feedback and monitoring learning. We implemented a quasi-experimental design in a first-year subject of a Digital Business degree programme at a Spanish public university. Throughout the semester, seven continuous assessment questionnaires were administered, in which we randomly varied the imposition of penalties for incorrect answers (−1/4 or no penalty). Given the limited sample size (a single cohort of 63 students), we employed an innovative bootstrapping technique to simulate multiple risk scenarios and classroom gender compositions, thus enabling robust statistical inferences regarding the impact of penalties.

The results suggest that removing penalties for incorrect answers increases students’ overall grades significantly. Notably, students benefit relatively more from environments without penalties. Interaction analysis reveals that a higher proportion of female students in the classroom actively improves the group’s average performance; however, this positive effect is negatively attenuated by penalties. This outcome suggests that assessment environments with penalties affect female students’ performance disproportionately.

This study makes several contributions to the existing literature on academic performance, assessment design and gender-based disparities in education. Methodologically, we introduce a novel approach that combines within-subject comparisons with large-scale bootstrap simulations to model classroom-level outcomes under varying conditions of evaluative risk. This simulation-based strategy enables us to estimate how hypothetical changes in penalty structures and gender composition might affect group performance, offering a replicable framework for analysing institutional sensitivity to risk.

Our study complements Montolio and Taberner’s (2021) quasi‑experimental analysis of a high‑stakes test pressure—operationalised as exam weight and time constraints, showing that the gender gap widens under higher pressure and narrows or reverses when pressure is low. By contrast, we isolate evaluation risk by manipulating penalties for wrong answers within a low-stakes, continuous assessment environment, extending individual-level estimates with bootstrap classroom composition simulations to leverage a significantly smaller volume of data. This design reveals a robust risk × female‑share interaction at the group level that was not addressed in the authors’ framework (Coffman & Klinowski, 2020; Montolio and Taberner, 2021; Iriberri & Rey‑Biel, 2021).

Theoretically, the findings provide empirical support for the hypothesis that evaluation risk interacts with gender composition to shape academic outcomes. While previously cited research has demonstrated gender differences in risk aversion and test-taking behaviour, this study extends those insights from the individual to the group level.

Lastly, we interpret the results through the lens of academic resilience, highlighting heterogeneous adaptive responses to evaluation pressure. Although the study does not measure resilience directly, the observed interaction patterns indicate that institutional stressors may pose a greater challenge to female students’ performance sustainability. These insights have practical implications for designing fair and inclusive higher education assessment systems.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows. Section 2 presents a review of the literature. Section 3 details the theoretical framework and hypotheses. Section 4 describes the methodology and study cohort. Section 5 presents the statistical analysis results. Section 6 discusses the implications of the findings in the context of the existing literature, possible theoretical and practical implications and limitations. Finally, Section 7 concludes by summarising the main findings and avenues for future research.

Literature reviewThe design of higher education assessment systems is not a neutral process since decisions concerning how to measure knowledge can have far-reaching implications for gender equity. One of the most controversial areas is the use of penalties for incorrect answers on multiple-choice tests. The academic literature on this topic presents a dynamic and unresolved debate, with two main schools of thought offering competing explanations for the impact of such penalties on the gender achievement gap. Our theoretical framework breaks down that debate to frame the research questions and hypotheses of this study.

Incorporating penalties for wrong answers may improve assessments’ validity and accuracy. The underlying theory of this assumption is that such scoring systems isolate actual student knowledge more effectively by deterring random responses, thereby benefitting those who are more prepared (Espinosa & Gardeazabal, 2010). From this perspective, penalties favour female students. A substantial body of empirical evidence indicates that women tend to have higher than average academic performance and dedication (Fortin et al., 2015). Therefore, a system that rewards preparation and punishes guessing should benefit this group.

Following this logic, several empirical studies have not found any negative impact of penalties on female students’ performance. For example, Funk and Perrone (2016) concluded that although women show greater risk aversion and may skip more questions, their superior preparation compensates for this effect, and they obtain higher final scores than their male peers. Similarly, in a study using a large sample of college entrance data, Akyol et al. (2022) determined that female and better-prepared students are more risk-averse; however, this tendency does not translate into a significant disadvantage in final scores. From this perspective, risk aversion is not construed as an irrational behaviour, but rather, an adaptive strategy employed by good students who prefer the certainty of not risking possible penalties.

By contrast to the above view, a robust and extensive body of research firmly grounded in behavioural economics has argued that error penalties introduce a systematic bias that undermines female students. The central argument of this position is consistent and has demonstrated gender differences in decision-making under risk, showing that women are more risk-averse than men in a wide variety of economic and experimental contexts (Eckel & Grossman, 2008; Croson & Gneezy, 2009; Baldiga, 2014; Manian & Sheth, 2021).

In the context of an exam, increased risk aversion manifests as a lower willingness to answer questions when uncertain about the correct answer (Iriberri & Rey-Biel, 2021). The mechanism is straightforward: when doubtful about the answer to a question, a more risk-prone student (usually male) may choose to answer randomly, whereas a more risk-averse student (usually female) may choose to skip the question. As a result, female students tend to leave more questions blank than their male peers, which leads to a lower final score in a system with penalties, even when they possess an equivalent level of knowledge (Pekkarinen, 2015; Espinosa & Gardeazabal, 2020; Saygin & Atwater, 2021). Consequently, several studies have shown that eliminating the penalty for incorrect answers is an effective measure for addressing the gender gap in test scores (Coffman & Klinowski, 2020).

In general, idiosyncrasies regarding the risk of making a mistake in a decision can alter the result. In various fields, this idiosyncratic difference may be attributed to gender differences. From a broader perspective, a growing body of research has demonstrated that risk disparity persists in various areas due to a lack of understanding of how to address differing risk positions and circumstances. For example, one study (Enri-Peiró et al., 2024) revealed how the educational process and the conditions for women’s success determine different levels of female entrepreneurship and better or worse sustainable development and gender equality outcomes. Similarly, another study found that gender differences in entrepreneurship indicate variations in risk-taking capacity between men and women; for example, in the initial decisions and the methods used to finance an investment project (Figueroa-Domecq et al., 2020).

Closer to the field of education, concerning financial skills and knowledge, Muñoz-Céspedes et al. (2024) found that when endeavouring to classify results correctly, the design of interviews and questions reveals significant differences between men and women in terms of different financial considerations, such as risk and different perceptions of each group’s knowledge.

The tension between these two seemingly contradictory bodies of literature implies the existence of a key moderating factor in the level of pressure or ‘stakes’ on the assessment. Evidence has indicated that gender differences in performance are amplified in high-pressure environments, such as college entrance exams or tests that carry significant weight in awarding the final grade. Men’s performance tends to improve in such contexts, while women are more susceptible to underperforming—a phenomenon known as drowning or choking under pressure (Baumeister, 1984; Azmat et al., 2016; Montolio & Taberner, 2021). This differential effect has been attributed to several psychological factors that extend beyond simple risk aversion.

Regarding tests, the differing risk perception indicates that women experience stronger test anxiety in higher education, which may interfere with cognitive processes during testing (Eman et al., 2012; Núñez-Peña et al., 2016). The mechanism may be better described as risk and loss aversion (Karle et al., 2022). These latter authors indicate that loss aversion is a more intense concept of prospect theory, which posits that the psychological impact of losing something is significantly higher than that of gaining an equivalent amount. In a penalty test, students risk a potential loss of points (from an incorrect answer) and face the loss of points already earned if they fail. This framing as a loss can intensify caution and decision paralysis, particularly for individuals who are more pressure-sensitive (Shurchkov, 2012).

In summary, the literature remains divided on whether penalising wrong answers ultimately helps or harms students, especially with respect to gender disparities. One line of research argues that negative marking improves assessment fairness by rewarding well-prepared students (thus potentially favouring women), whereas the opposing view contends that such penalties deter risk-averse test‐takers (often female) disproportionately and thereby widen gender performance gaps. This unresolved debate points to the importance of examining assessment designs beyond high-stakes settings. Accordingly, a theoretical framework is needed to examine how these penalty effects play out in low-stakes environments. The methodology outlined in the following section has been designed to investigate the specific research questions posed in this study.

Theoretical framework and hypothesis developmentOur literature review reveals a critical gap wherein the majority of extant research has focused on high-stakes tests. However, much less is known about how gender dynamics operate in low-stakes settings, such as those used for continuous assessment.

This type of assessment, using questionnaires, assignments and partial tests, is a pillar of the existing learning model designed to provide continuous feedback for students and teachers (Ramsden, 2003). Although pressure is a key moderating factor, it is not possible to extrapolate findings directly from high-stakes studies to low-stakes studies.

This gap leads to our main research question. How does the introduction of penalties for incorrect answers affect academic performance in the context of low-stakes continuous assessment, and does this effect vary by students’ gender?

Although the study does not include direct measurement of individual resilience, the differential response to evaluation pressure, particularly the steeper performance decline observed among female students under penalty conditions, can be interpreted as an indirect indicator of academic resilience. In this context, resilience is understood not merely as a personal trait but as indicating students’ adaptive capacity to maintain performance under challenging assessment environments. The gender-based sensitivity to evaluative risk observed in this study expands the literature on resilience in academic contexts, particularly in terms of how institutional design may amplify or mitigate such disparities.

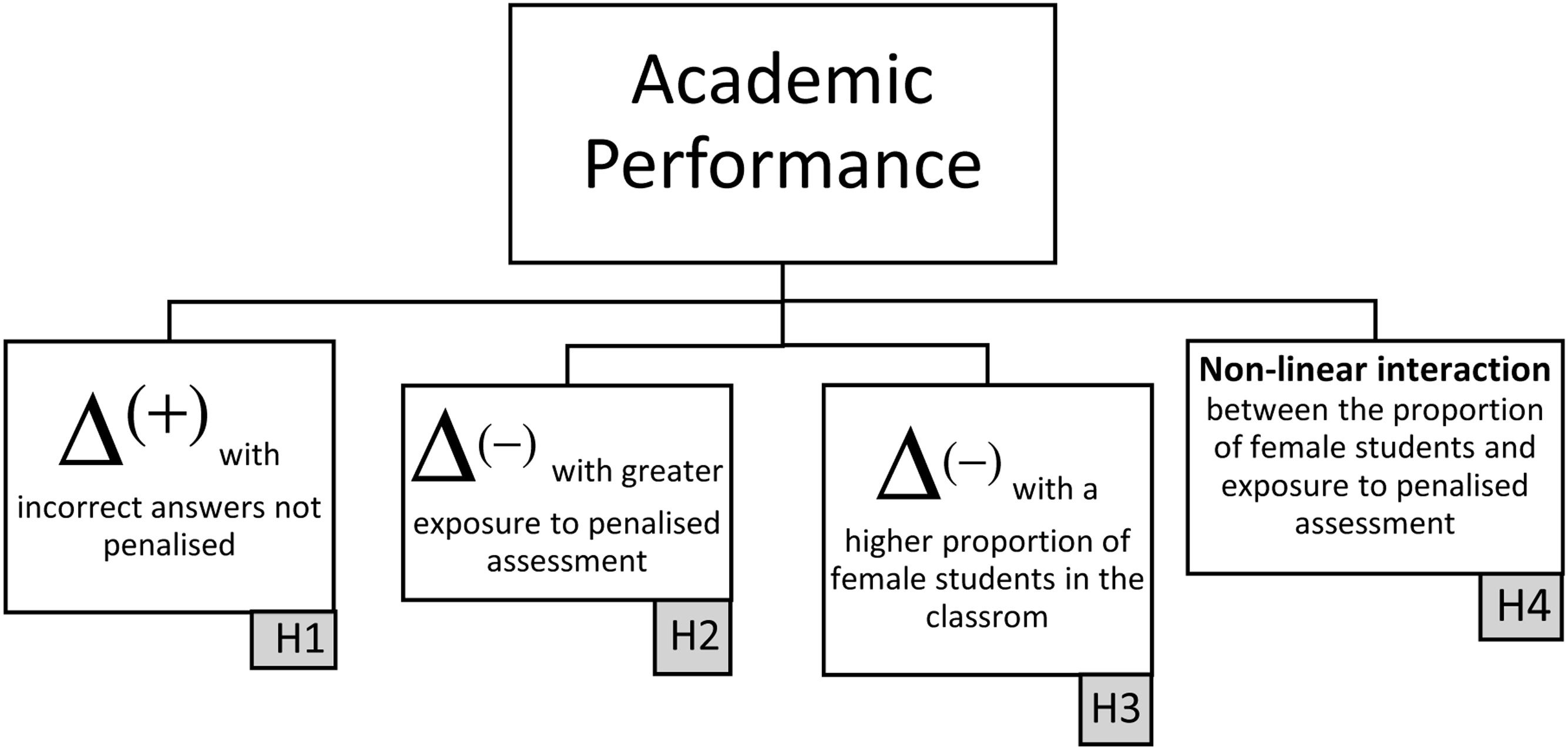

Research hypothesesAlthough this study adopts an exploratory and simulation-based approach, our empirical strategy is grounded in a set of testable hypotheses derived from the structure of evaluation systems and the previous literature on risk sensitivity and gender differences in the academic context. The following hypotheses guide our analysis:

H1. Students perform better on multiple-choice assessments when incorrect answers are not penalised.

This is examined using a within-subject design to compare students’ performance on penalised as opposed to non-penalised quizzes using observed data.

H2. In simulated classroom scenarios, greater exposure to penalised assessments is associated with lower group-level academic performance.

We assess the aggregated effect of evaluative risk, quantified as the proportion of penalised quizzes, using simulation-based regression models without considering gender composition.

H3. Classroom groups with a higher proportion of female students are expected to perform better in low-risk assessment environments (i.e. when no penalties are applied).

This hypothesis reflects gender-based differences in academic performance in neutral conditions.

H4. Classroom groups with a higher proportion of female students are expected to experience steeper performance declines as evaluative risk increases (i.e. where more quizzes apply penalties for incorrect answers).

This implies that predominantly female classes are more sensitive to risk-based assessment environments.

Although H1 and H2 are related conceptually, they operate at different analytical levels and rely on distinct methodological approaches. H1 is grounded in observed data, employing a within-subject design that compares individual student performance across both penalised and non-penalised quizzes. This direct comparison enables our assessment of the same individuals’ performance differences attributable to the presence or absence of penalties.

In contrast, our examination of H2 adopts a simulation-based strategy to examine the broader, systemic effects of evaluation risk. Specifically, we model how average academic performance varies in proportion to penalised assessments in hypothetical classroom scenarios. While H1 provides an empirical benchmark based on actual student behaviour, H2 extends the analysis through a controlled simulation to explore the aggregate consequences of varying exposure to penalties.

We also test H3 and H4 using simulated data via bootstrap resampling from a single real-world academic cohort. This approach enables us to construct a wide array of hypothetical classroom compositions with various gender ratios and the proportion of penalised assessments. Accordingly, references to ‘classrooms’ or ‘groups’ throughout the analysis should be understood as simulated constructs rather than independently observed educational settings.

It is important to clarify that the intent of these hypotheses is not to establish causal inferences in the strict sense, but rather, to uncover consistent empirical regularities under systematically varied conditions. Our analysis endeavours to provide insights into how academic performance may be influenced by the interaction between evaluation risk and gender composition across a spectrum of plausible academic environments.

Fig. 1 illustrates the framework of our four research hypotheses linking academic performance to assessment design and classroom gender composition. Each hypothesis is represented as a directional, positive or negative relationship, highlighting expected changes in performance under different evaluative conditions. The figure synthesises the study’s analytical structure, with particular emphasis on the influence of penalisation and gender on shaping academic outcomes.

This study is, therefore, situated at the intersection of these hypotheses, analysing the differing impact of penalties in the specific and under-explored context of low-stakes examinations that define formative assessment at the university level to provide valuable evidence and help resolve this theoretical tension.

Methodology and dataContext of the studyThe study was based on a first-year undergraduate applied economics module taught at a university in Spain during the 2023–2024 academic year as part of a Digital Business bachelor’s degree (ISCED 6). Out of the 69 students enrolled in the class, 63 (91.3 %) gave informed written consent to participate in this investigation. Participation was voluntary and not incentivised, and non‑participation incurred no grading consequences. The Research Ethics Committee of the Universidad Rey Juan Carlos of Madrid approved the study on 1 June 2023 (approval number 1104,202,317,723). The first quiz was administered on 14 September 2023, and the final quiz took place on 21 December 2023.

The course, comprising 14 weekly topics, evaluated students through seven bi-weekly quizzes and a final comprehensive exam. The quizzes featured 30 multiple-choice questions, except for the final exam, which included 50 questions, each with a one-minute time limit and assigned equal weight in the final grade. The quizzes were provided in class using the university’s Moodle platform under a Bring Your Own Device scheme, following the recommendations by Sundgren (2017). Multiple-choice questions were also designed under standard guidelines (Struyven et al., 2005; Brame, 2013). We implemented a within‑subject, between‑quizzes fixed assignment in which quizzes 1–3 and 8 applied no penalty, whereas quizzes 4–7 applied a − 0.25 penalty per wrong answer. Topic coverage and item difficulty were balanced across conditions via instructor review. Students knew this information in advance as the pedagogical strategy was to encourage them to start studying early (Ramsden, 2003). We expected that if the exam penalised incorrect answers, students’ strategy would be more conservative, answering only the questions they were sure would be correct. Similarly, we assumed that students’ effort would increase as the final exam approached.

Experimental designThe structure of the assessment system offered a quasi-natural experimental setting in which all students completed the same set of eight quizzes. This consistent exposure to both conditions enabled within-subject comparisons of individual performance across evaluative contexts.

As noted previously, we implemented a simulation-based approach using bootstrap resampling to extend the empirical analysis. Each student’s performance data included eight observed quiz scores, a gender indicator and binary flags indicating whether a quiz was penalised. The resulting data were then used to generate synthetic learning environments in which the proportion of penalised assessments varied systematically.

For each simulation, we computed a synthetic quiz average (meanindex_8) by randomly resampling (with replacement) eight quiz scores per student. This process was repeated to create a simulated classroom composed of 63 students. By varying the share of penalised quizzes (pr_risk) in each simulation, we modelled how different configurations of evaluative risk influenced academic performance.

Student gender was preserved across simulations, enabling us to examine potential gender-based differences in sensitivity to penalties. We also aggregated gender composition at the classroom level to compute the proportion of female students (female_proportion), enabling the analysis of how group-level gender dynamics moderate the relationship between evaluative risk and performance outcomes.

Our procedure simulated hypothetical scenarios of academic evaluations. We did not intend to estimate population parameters per se, but rather, to explore the behavioural and structural implications of assessment design through resampling-based experimentation.

Key variable definitionsTo analyse the effect of penalties and gender composition on student performance, we defined the following variables:

mean_risk: This variable represents each student’s average score obtained for the four quizzes that included a penalty for incorrect answers (quizzes 4–7).

mean_no_risk: The average score for each student across the four quizzes that did not include a penalty for incorrect answers (quizzes 1–3 and 8).

mean_8: The average performance of a simulated classroom group, which was calculated by first computing an individual mean based on the eight quiz scores for each resampled student, randomly selected with replacement from actual assessments (including penalised and non-penalised quizzes). We then averaged these individual means across all 63 students in the simulated group to produce a single group-level score. Therefore, mean_8 reflected a hypothetical class’s overall performance under a specific configuration of evaluative risk.

Evaluative risk (pr_risk): This variable denoted the proportion of penalised quizzes selected in each simulation, ranging from 0 (no penalised quizzes) to 1 (all quizzes penalised). This variable was a proxy for evaluative pressure intensity, capturing the degree to which students were exposed to loss-based assessment conditions. All references to ‘evaluative risk’, ‘risk intensity’ or ‘assessment pressure’ refer specifically to the pr_risk value.

female: A binary variable indicating the student’s gender (1 = female, 0 = male), used for individual-level analysis.

female_proportion: The proportion of female students in each simulated classroom, which was calculated in every iteration of the bootstrap simulation to allow our analysis of gender composition effects.

risk×female_proportion: An interaction term between pr_risk and female_proportion that was introduced into the regression model to assess whether the effect of penalties on group performance differed according to gender composition.

Our methodological strategy combined descriptive statistics, non-parametric inference, simulation-based resampling and regression modelling with interaction terms. This multi-method approach was chosen to provide robust exploratory evidence and simulation-driven insights, particularly considering the moderate sample size and mixed structure of the assessment environment.

Descriptive analysis of the original sampleWe began by examining the empirical distribution of actual quiz scores, comparing the average grades under penalised and non-penalised conditions. Table 1 in Section 5 presents the descriptive statistics (mean, median, standard deviation (SD) and range) for each condition. These initial comparisons present the observed sample differences in student performance under penalised and non-penalised conditions, providing the baseline descriptive evidence before the simulation analysis. In addition, we used graphical representations (histograms with density curves) to evaluate shifts in distributional shape and central tendency.

Permutation test for within-subject comparisonsWe implemented a paired permutation test to examine whether observed mean differences between penalised and non-penalised quizzes were statistically significant. This method is particularly suitable given that the assumption of normality is violated, as confirmed by the Shapiro–Wilk test. Permutation tests provide a robust, non-parametric alternative to classical parametric methods, particularly in small samples and non-normal distributions. Originally developed by Fisher and Pitman in the 1930s, permutation methods have gained traction in educational and behavioural research owing to their flexibility and minimal assumptions (Berry et al., 2025; D’Agostino & Massaro, 2003; Good, 2005; Chow & Teicher, 2012). The test relies on the principle of exchangeability, whereby the order of paired observations is randomly shuffled to simulate the null hypothesis of no effect. This approach provides a reliable alternative to the Student’s t-test, which is sensitive to deviations from normality.

Bootstrap resampling with replacementWe used a bootstrap algorithm to simulate a variety of plausible risk environments and evaluate performance under different penalty compositions. A detailed simulation procedure was implemented to examine how students’ performance may vary under different levels of evaluative risk. The bootstrap resampling procedure is described in subsection 4.5. For foundational treatments of bootstrap methodology, see works by Efron and Tibshirani (1994), Chernick and LaBudde (2011), Davison and Hinkley (1997) and James et al. (2013).

Ordinary least squares regression with interaction termsWe estimated linear models using mean_8 as the dependent variable to analyse how exposure to evaluative risk and gender composition affect academic performance. Predictors included pr_risk, female_proportion and their interaction (pr_risk×female_proportion). This model enabled us to quantify the direct effects of risk and gender composition and whether the effect of penalisation intensifies or attenuates depending on the proportion of female students in the simulated classroom. We interpreted the interaction term according to the hierarchy principle (Hastie et al., 2009), which states that if an interaction is significant, the main effects involved should persist in the model even if they are not individually significant.

Reproducibility protocolsAll simulation scripts were initialised with a fixed random seed to ensure the transparency and reproducibility of results.

Simulation algorithm to model risk environmentsThe purpose of the simulation was to estimate how average academic performance varies under different proportions of penalised as opposed to non-penalised assessments. Since each student completed eight quizzes, which included penalties and no penalties in equal number, we used a bootstrap-based sampling strategy to generate virtual classroom configurations that varied in their exposure to penalty-based evaluation.

Specifically, we designed a simulation algorithm based on bootstrap resampling, with each step in the process designed with a specific educational and analytical rationale, as follows:

- •

Random sampling of 63 students with replacement, which simulates a virtual classroom composed of individuals with different academic profiles, reflecting the natural diversity found in real-life university settings.

- •

Random selection of 8 quiz scores (with replacement) per student, which emulates the possible combinations of exam exposures a student might face. Since the original eight quizzes included penalised and non-penalised formats, each simulated student’s average score (mean_8) captured how their final performance might change depending on the specific risk environment they experienced.

- •

We classified the eight scores into those corresponding to non-penalised quizzes (E1, E2, E3, E8) and those from penalised quizzes (E4–E7) to construct the key measures:

No-risk group: Number of non-penalised scores.

Risk group: Number of penalised scores.

- •

We calculated evaluative risk (pr_risk) using the proportion of penalised quizzes among the eight quizzes administered. This variable captured the global level of evaluative risk faced by a student in each simulation, serving as an indicator of exposure to penalties to evaluate how overall test risk impacts group and individual performance.

- •

Repetition across one million simulations: We repeated the entire procedure to construct a large synthetic dataset, storing overall average score, risk proportion (pr_risk), gender composition and disaggregated average scores by gender for each iteration.

- •

Visualisation and modelling: To complement the regression models, we examined how simulated average performance varies with evaluative risk across gender compositions. The corresponding graphical analysis is reported in Section 5.

The algorithm calculated an individual average score (mean_8) for each student based on eight resampled quiz results for each simulation. We then aggregated these individual averages to obtain a group-level mean score to reflect the average performance of a simulated class under a given evaluative risk level (pr_risk) and gender composition (female_proportion). The group-level mean of mean_8 was used as the dependent variable in the regression model presented in Section 5.3.

This enabled us to analyse how students’ performance reacts to increased exposure to evaluative risk and whether this effect differs systematically by gender. Notably, although the number of actual assessments per student was fixed, this simulation enabled us to model heterogeneity in classroom assessment environments without altering the original data. We used the resulting dataset to estimate linear regression models with interaction terms between evaluative risk and gender composition, which enabled us to examine direct and moderating effects.

The use of sampling with replacement is grounded in its capacity to simulate how the same group of students might respond to varying exam penalty levels by effectively modelling a range of hypothetical assessment scenarios. While the findings are not intended to be generalised to the broader student population, this bootstrap-based approach enables a robust estimation of how gender and penalty severity interact within the observed sample. This method follows well-established bootstrap principles (Efron & Tibshirani, 1994) and, while distinct in approach, yields results that align with previous educational research demonstrating gendered responses to exam penalty structures and uncertainty (Karle et al., 2022).

ResultsThis section presents the baseline empirical findings organised around the four hypotheses described in Section 3.

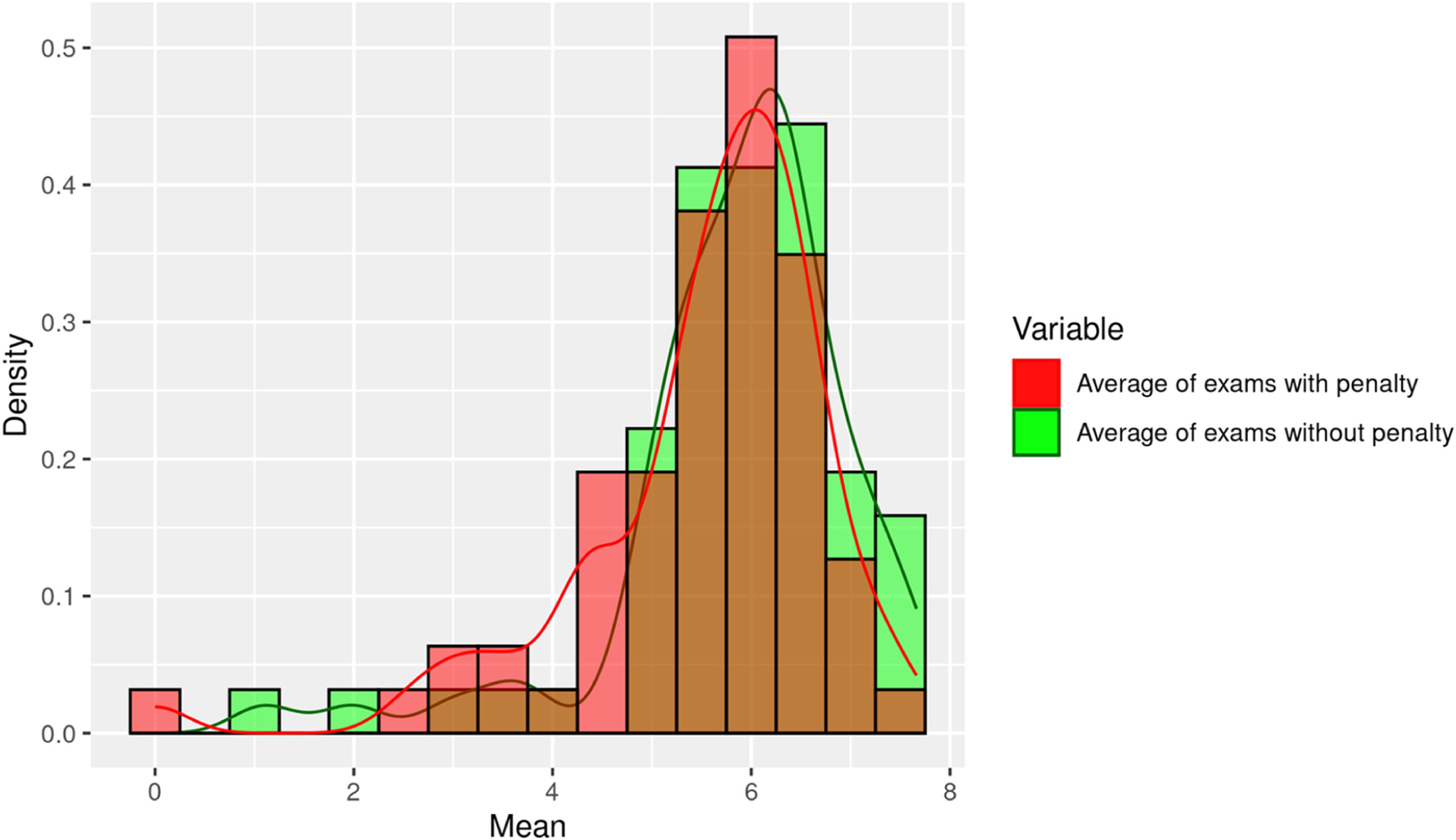

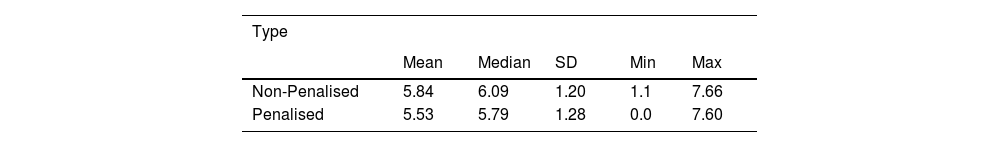

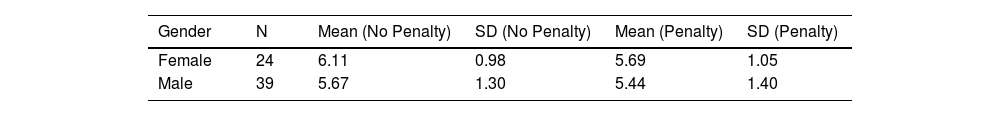

Descriptive analysis and H1Out of the 63 anonymised students enrolled, 24 students (38.1 %) were female and 39 (61.9 %) were male. Table 1 presents the summary statistics of quiz scores under penalised and non-penalised conditions. Students performed better in the absence of penalties, with an average score of 5.84 (SD=1.20) compared to 5.53 (SD=1.28) in penalised quizzes. The median values (6.09vs.5.79) also reflect this performance gap, showing the differences observed in the sample under both assessment conditions.

The scores in Table 1 represent the average performance per student, calculated as the mean of the four penalised and non-penalised quizzes completed by each participant.

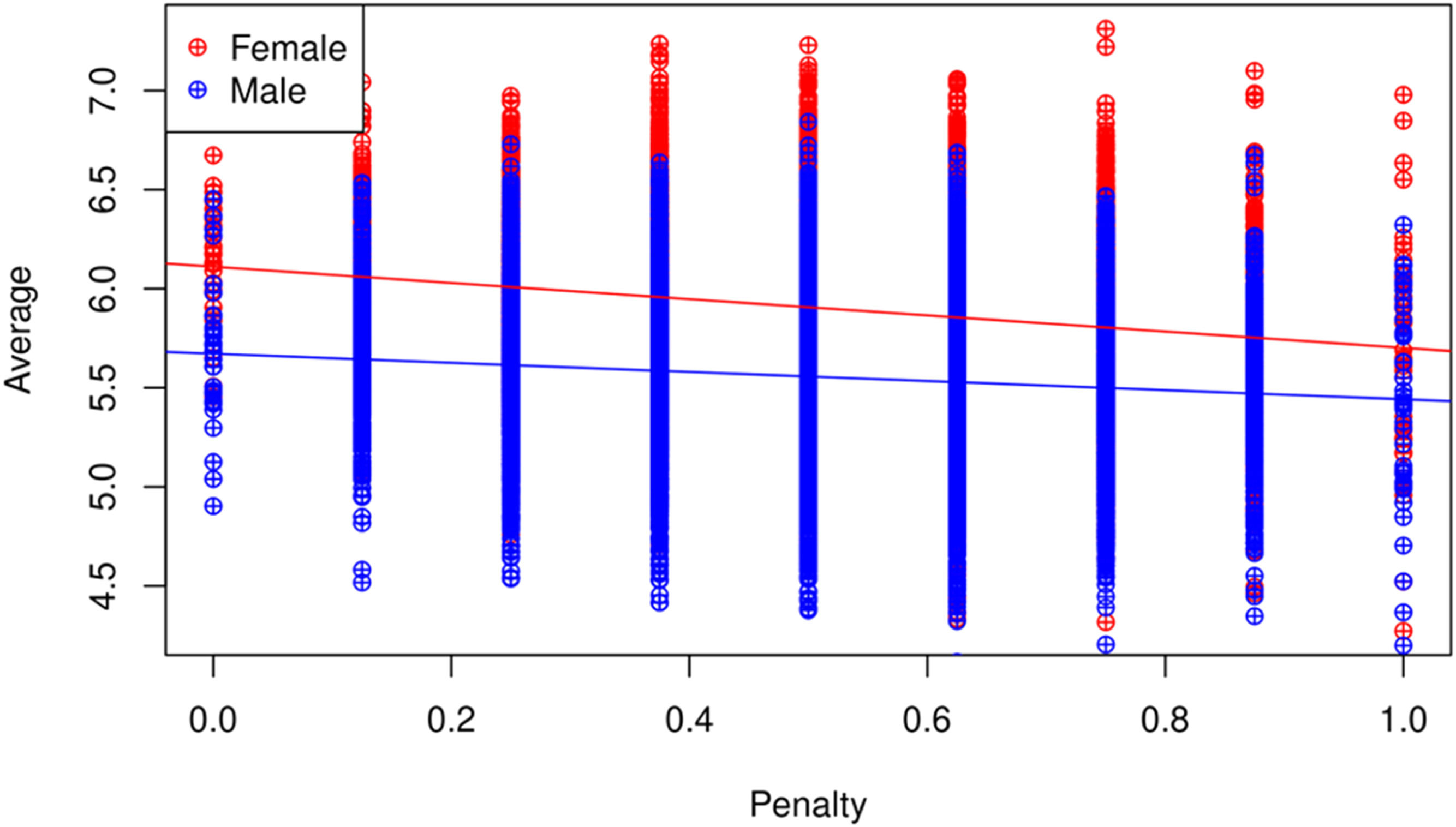

Table 2 presents the same statistics disaggregated by gender, revealing that female students outperformed their male counterparts under both evaluation conditions. In non-penalised quizzes, female students obtained a mean score of 6.11 (SD=0.98), as opposed to 5.67 (SD=1.30) for male students. Under penalised conditions, this difference narrowed slightly, with mean scores of 5.69 for female students and 5.44 for male students. However, the SD for male students was higher, indicating more variability and possibly less consistency under riskier evaluation conditions.

These findings offer initial support for the hypothesis that performance tends to deteriorate under penalisation and that this effect may be modulated by gender. In the following subsections, we explore the patterns observed here through inferential and simulation-based analyses.

To test H1, which proposes that penalised quizzes result in poorer student performance, we conducted a within-subject comparison using students’ average scores, computing individual averages as mean_risk and mean_no_risk.

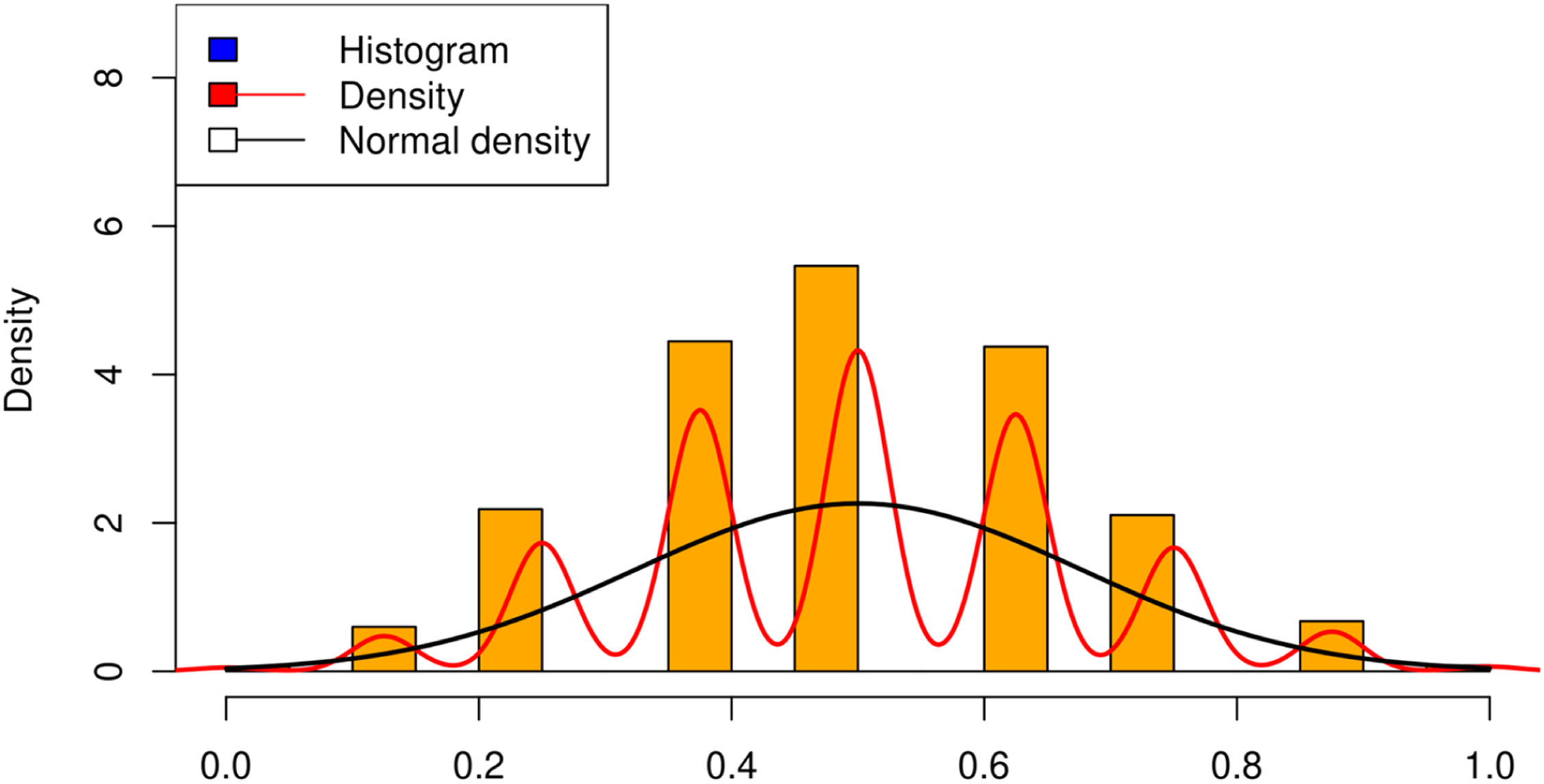

Fig. 2 presents overlaid histograms and density curves for both conditions. The distribution of non-penalised averages shifted to the right, indicating better performance than penalised quizzes.

We conducted Shapiro–Wilk normality tests to assess the validity of parametric testing. The results indicated that neither mean_no_risk (W=0.8615,p<0.001) nor mean_risk (W=0.8726,p<0.001) follow a normal distribution; therefore, any interpretation based on the t-test should be considered in light of this limitation.

Nevertheless, we applied a paired-sample t-test as our primary objective was to evaluate whether the difference in means reached statistical significance (Konietschke & Pauly, 2006). The test revealed a statistically significant difference between the two conditions, t(62)=−3.19, p=0.0023, 95%CI=[−0.50,−0.11]. The mean difference was −0.31, indicating that all students performed significantly better when no penalties were applied.

We employed two non-parametric approaches to address data non-normality and confirm robustness.

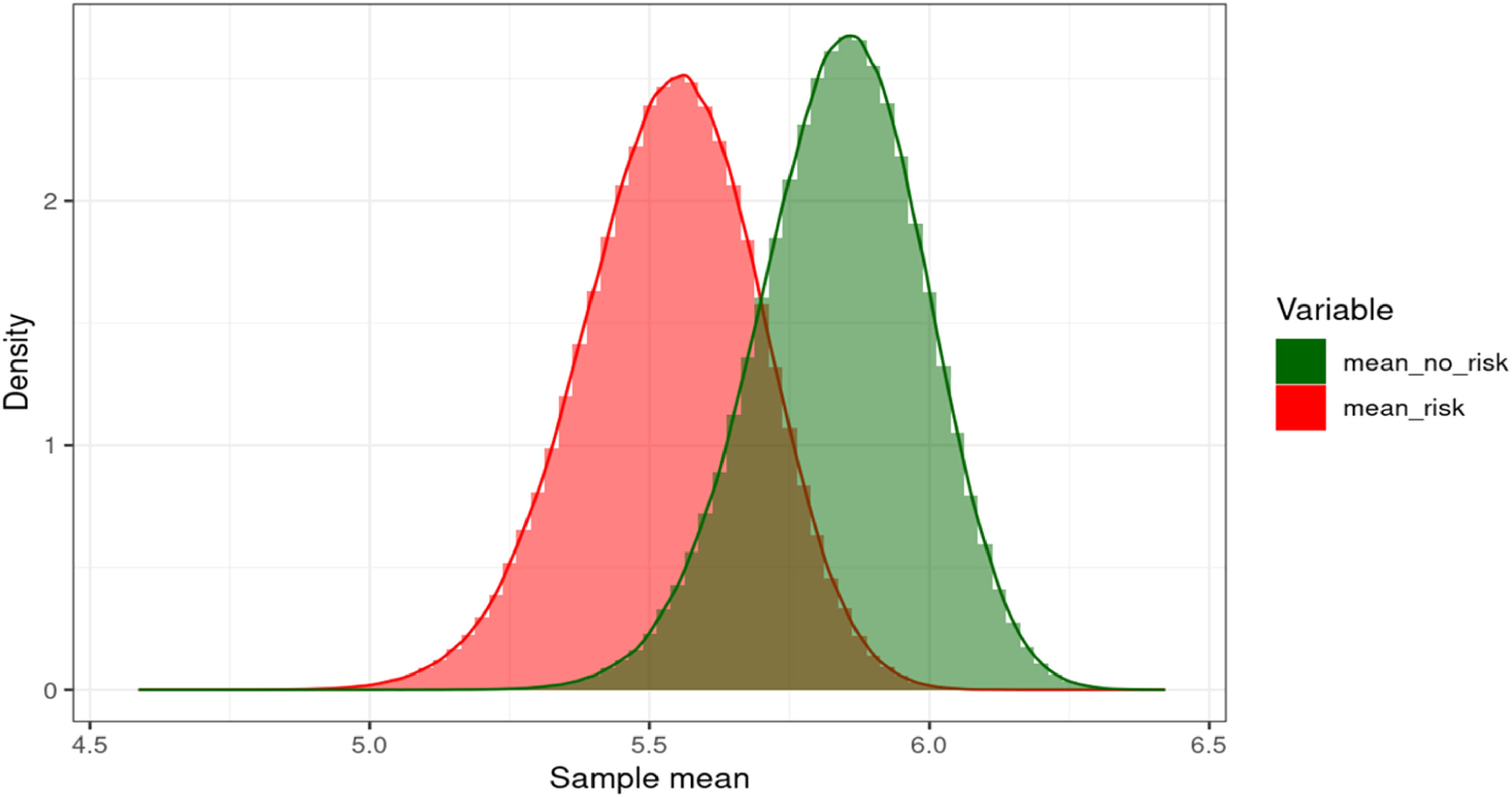

Bootstrap resampling. We performed one million resamples of the mean scores under both conditions. The resulting mean difference between non-penalised and penalised quizzes was 0.305 points, favouring the non-penalised condition. Bootstrap distributions in Fig. 3 are clearly separated, with negligible overlap between them, visually confirming the robustness of the difference.

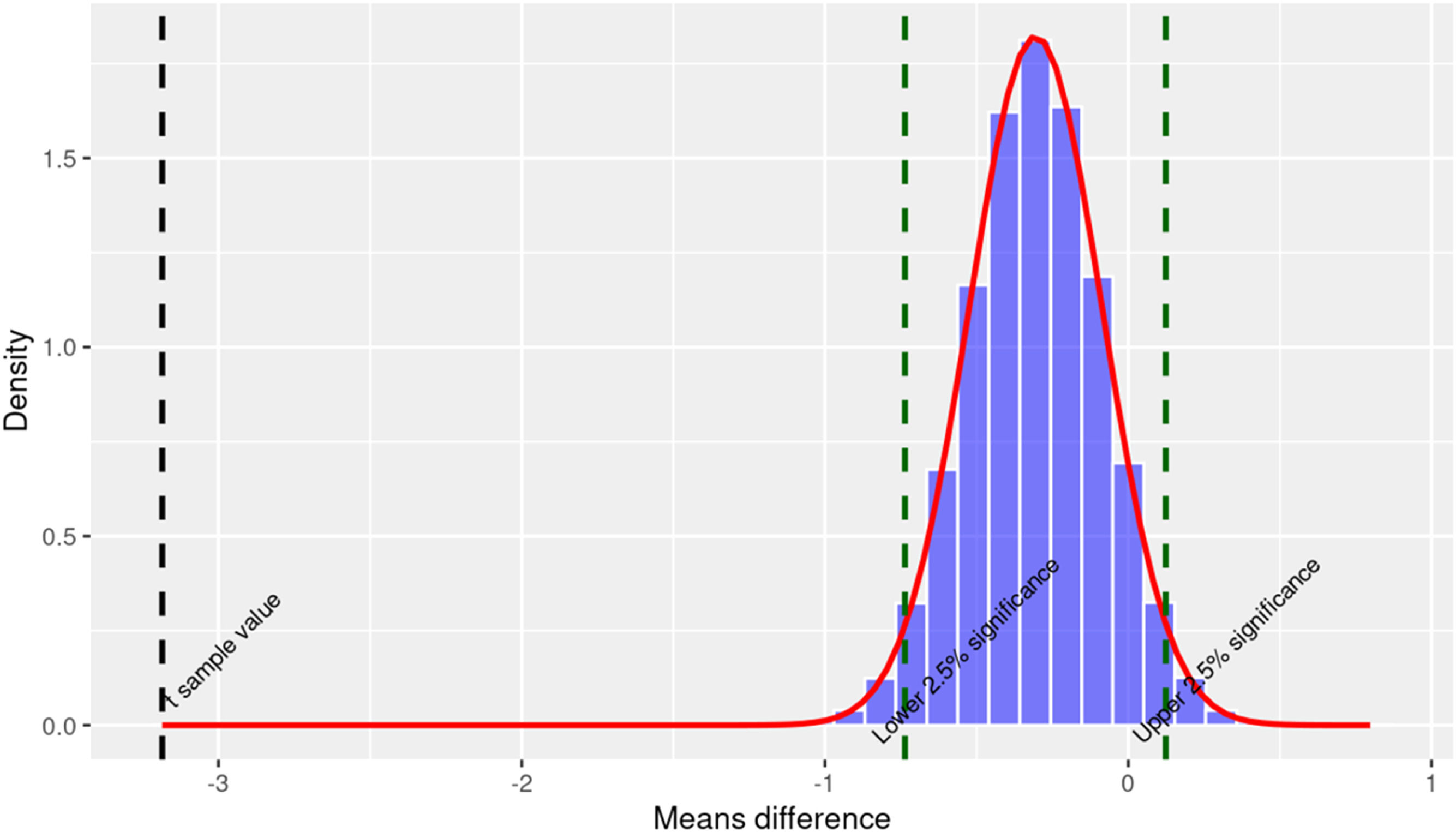

Permutation test. We implemented a permutation test with 10,000 iterations to evaluate the likelihood of observing a mean difference as large as that obtained under the null hypothesis of no effect. The observed statistic was again 0.305, and the associated p value was <2.2e−16, strongly rejecting the null hypothesis.

These findings strongly support H1, indicating that even in low-stakes, formative assessments, penalties can reduce average performance. This result is consistent with the literature in behavioural economics and educational psychology that highlights the effects of loss aversion and perceived risk on decision-making in academic environments (Baldiga, 2014; Núñez-Peña et al., 2016).

Fig. 4 shows the permutation distribution of paired mean differences between penalised and non-penalised quizzes. The observed value (0.305) falls well beyond the 5 % critical threshold, leading to a strong rejection of the null hypothesis of equal means.

As an exploratory step before fitting regression models, we examined the average performance of male and female students separately across varying levels of penalisation. Fig. 5 illustrates the relationship between the simulated average group score and the proportion of penalised quizzes (pr_risk), based on 10,000 resampled classroom configurations, which plotted separate linear fits for male and female students. A steeper decline in performance between predominantly female groups indicates a greater sensitivity to evaluative risk, which motivates the interaction model tested in the following subsection.

Simulating risk environments and average performance (H2)H2 posits that average student performance decreases as exposure to evaluative risk increases. To test this, we applied the bootstrap procedure described in Section 4.5. In brief, one million synthetic classroom observations were generated, each characterised by a mean performance score (mean_8) and a proportion of penalised quizzes (pr_risk).

Fig. 6 shows the distribution of pr_risk across simulations, which is approximately symmetric around 0.5. This balanced coverage of scenarios ensures that subsequent analyses capture both low- and high-penalisation environments adequately.

The simulated distribution of pr_risk is approximately symmetric, centred at ∼0.5, and closely resembles a bell-shaped curve. This pattern arises naturally from the resampling process and can be understood in light of the central limit theorem, which implies that sample proportions converge in distribution towards normality as the number of replications increases. Consequently, evaluative risk scenarios are most frequently concentrated around intermediate values, whereas configurations with very low or very high levels of penalisation occur less often.

Gender and risk interaction effects (H3 and H4)To test H3 and H4, we next estimated a linear regression model based on one million simulated classroom configurations generated via bootstrap resampling (as described in subsection 5.2). We assigned each student eight quiz scores, replacing their original results in each simulation, from which we calculated an individual average score (mean_8). These individual scores were then aggregated to determine the average performance of the simulated group of 63 students, which served as the dependent variable in our model.

This regression framework incorporated the proportion of penalised assessments (pr_risk), the proportion of female students in the simulated classroom (female_proportion) and their interaction. This enabled us to assess H3 empirically, which posits that predominantly female groups are more sensitive to evaluative risk, and H4, which indicates that the negative effect of penalisation is amplified when the proportion of female students increases.

The regression model is specified as follows:

The three predictors included in the model are defined in Section 4.3. Including an interaction term, which enabled us to test for non-additive effects to determine whether the risk effect depends on the group’s gender composition. The coefficients are interpreted as follows:

β1 reflects the effect of evaluative risk (pr_risk) on average score, holding gender composition constant. A negative value indicates that scores decrease as risk increases.

β2 measures the effect of an increased proportion of female students in low-risk conditions.

β3 captures how risk effect changes as the proportion of female students rises. A negative and significant coefficient indicates that predominantly female groups are affected more negatively by evaluative risk exposure, thus supporting H3 and H4. The interaction effect confirms that both individual and group gender compositions moderate the impact of evaluative risk on performance.

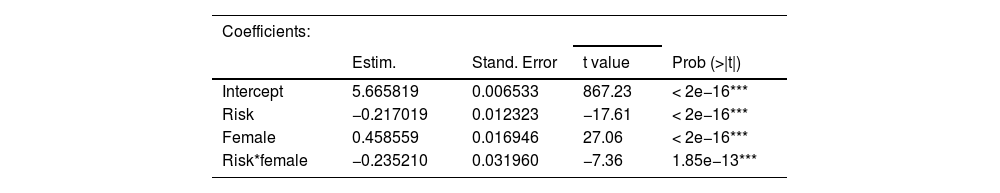

The results of the linear regression model estimated using one million simulated classroom configurations are presented in Table 3. All estimated coefficients are found to be statistically significant at the 0.1 % level, with low standard errors indicating a high degree of precision. The intercept is estimated at 5.666 (SE=0.0065), representing the expected average group score in a hypothetical class composed entirely of male students and with no penalised assessments.

Simulation model with one million replications.

Note: ***, ** and * indicate respective significance levels of 0, 0.001 and 0.01.

The coefficient for pr_risk is −0.217 (SE=0.0123;p<0.001), indicating that an increased proportion of penalised assessments is associated with a statistically significant deterioration in group performance. This negative relationship reflects the overall detrimental effect of evaluative risk on academic outcomes.

The coefficient for female_proportion is 0.459 (SE=0.0169;p<0.001), indicating that simulated groups with a higher proportion of female students tend to perform better on average under low-risk conditions. This positive effect indicates a performance advantage in predominantly female classrooms when penalties are absent.

The pr_risk×female_proportion interaction term is estimated at −0.235 (SE=0.0320;p<0.001), revealing that the negative impact of evaluative risk becomes more pronounced as the proportion of female students rises. This interaction effect indicates that the decline in group performance under penalised conditions is steeper in classrooms composed of more female students.

The model explains 2.75 % of the total variance in simulated group performance (R²=0.0275; adjustedR²=0.0275), which, although modest, is consistent with expectations in a highly controlled simulation using limited predictors. As noted previously, it is crucial to note that the intent of this study is not to define the full set of variables that influence academic performance per se, but to examine whether performance is affected by the interaction between gender and risk and the presence of penalties in assessment tests. The F-statistic confirms that the model is found to be jointly significant (F=9427;p<0.001), and the residual standard error remains low (0.345), indicating a reasonable model fit given the simplicity of the specification and the nature of the resampled data.

These regression results provide empirical support for the three central hypotheses of the study. First, the negative and statistically significant effect of pr_risk confirms H2, indicating that greater exposure to penalised assessments reduces average group performance systematically in simulated classroom environments.

Second, the positive and significant coefficient for female_proportion supports H3, indicating that predominantly female groups tend to achieve better performance under low-risk conditions. This result aligns with previous literature on gender differences in academic behaviour in neutral or formative evaluation settings.

Finally, the statistically significant negative interaction term between pr_risk and female_proportion supports H4, demonstrating that the adverse impact of evaluative risk intensifies in those classrooms with a higher proportion of female students. This finding suggests an increased sensitivity to penalisation in predominantly female settings, reinforcing the argument that assessment design interacts with gender composition in shaping academic outcomes.

Discussion, contributions and limitationsOur results examine the interplay between punitive environments and gender proportions in academic settings, revealing their multifaceted impact on student performance. While previous cited research has acknowledged the general detrimental effect of punitive environments on grades, this study offers deeper insights into the heterogeneous influence of these environments for male and female students in low-stakes exams. (Azmat et al., 2016; Iriberri & Rey-Biel, 2019, 2021).

Descriptive statistics (Table 1) indicate that students tend to achieve higher average scores in non-penalised quizzes than in penalised ones. Fig. 2 further illustrates this sample-level difference, showing a rightward shift in the distribution of scores when penalties are absent. The statistical significance of this performance gap is further confirmed by inferential analyses, including non-parametric tests (Konietschke & Pauly, 2006), bootstrap resampling and permutation procedures, which consistently demonstrate that non-penalised settings yield higher average performance. Quantitatively, these tests reveal a mean increase of approximately 0.31 exam points in favour of the non-penalised condition.

Beyond the overall effect, the analysis reveals a noteworthy gender dimension wherein female students outperform their male counterparts in non-punitive environments. However, as the penalty (risk) escalates, female students demonstrate a steeper performance decline than that of male students (Fig. 5). This finding suggests that female students benefit more from a lack of penalties, as illustrated in other studies (Bechar & Mero-Jaffe, 2013; Stoet et al., 2016).

This research quantifies, within the framework of the hypothetical scenarios generated through simulation, the impact of varying risk levels, showing that a punitive environment is associated with an estimated reduction of 0.22 points in average grades (Table 3). This contrast underscores the influence of gender dynamics on academic performance across different evaluative contexts (Stoet et al., 2016). Furthermore, we identify an adverse interaction effect, indicating that increased risk intensifies the decline in average performance in simulated classrooms with a higher proportion of female students. This suggests that, under punitive evaluative conditions, female students may face additional challenges in their academic outcomes, potentially widening the gender gap (Hodge et al., 2018).

Moving beyond individual factors, we employ a regression model that includes the interaction between the proportion of exams with penalties and the proportion of women in the class. This comprehensive approach reveals that while the net effect of the risk environment on grades is modest, a higher proportion of women in the group elicits better performance. However, the interaction between risk and the proportion of women remains negative.

Theoretical and practical implicationsBeyond the scope of our results, this study contributes a methodological framework that can be easily applied to other academic settings. Therefore, this study also advances theory and practical implications in several interconnected domains.

Our findings extend current prospect theory reasoning on risk and loss aversion (Kahneman & Tversky, 1979) from the individual decision-making context to the classroom level. By modelling the interaction between the proportion of penalised assessments and gender composition, we show that perceived evaluative risk is not merely an individual psychological trigger but also an emergent structural property that shapes collective performance. The simulation results suggest that penalty-based assessment frameworks tend to produce statistically significant reductions in academic performance within considered hypothetical scenarios. Moreover, these effects appear more pronounced in settings with a higher proportion of female students, consistent with the greater risk aversion documented in the literature (Hodge et al., 2018; Eckel & Grossman, 2008).

The study also integrates two previously parallel research lines of gendered risk behaviour (Eckel & Grossman, 2008) and assessment design (Espinosa & Gardeazabal, 2010) into a single analytical framework. Within the simulation context, the significant pr_risk×female_proportion interaction (β = −0.24, p < .001) empirically links cognitive economics constructs to pedagogical outcomes, refining our understanding of how assessment rules can affect performance gaps.

Regarding the practical implications, this study contributes methodologically by demonstrating that large-scale bootstrap simulations can extract stable interaction estimates from a single, small cohort, overcoming the limitations intrinsic to small sample size. This design provides instructors and researchers with a practical template when a full randomisation across classes is infeasible. This allows for meaningful comparisons of the effects of risk, gender and their interaction across different instructional units (students, teachers and subjects) or educational settings, yielding robust conclusions even with the sample sizes typical of standard classroom cohorts. In addition, the methodology allows us to uncover statistically significant relationships between evaluative risk, gender composition and student outcomes—relationships that might otherwise remain hidden in conventional small-sample educational analyses. These contributions reposition evaluative risk as a theoretically tractable moderator in the study of gender equity in higher education.

This approach also enables a comparative analysis of how institutional design influences performance dynamics. The findings suggest that evaluative risk, when combined with gender composition, serves as a structural factor influencing collective performance. Conceptually, this relationship can be linked to academic resilience, as higher levels of evaluative risk require greater adaptive capacity from students. Resilience, in this context, may be understood as the ability to sustain or recover performance under adverse assessment conditions. Accordingly, the results suggest that assessment systems should be sensitive to gender-based differences in response to evaluative stress, as unequal exposure to risk may also translate into unequal demands for resilient responses.

The findings also provide valuable insights for educators and policymakers seeking to create environments that foster both learning and exam performance, while also supporting an inclusive and equitable educational landscape. It follows that evaluation practices should be designed in ways that do not erode students’ academic resilience, for example, by adjusting learning management system (LMS) settings, implementing faculty training workshops and pilot evaluation schemes, replacing −0.25 penalties with non-penalty alternatives that apply confidence marking or introducing formative ‘risk rehearsals’ before summative tests.

LimitationsThis study has several strengths that advance our understanding of how penalty-based assessment environments influence gender disparities in academic performance by cohorts.

However, recognising these positive contributions also requires acknowledging potential limitations as the natural boundaries of these advances. Our reliance on data from a single undergraduate course at one institution is a necessary trade-off for inference because it may limit generalisability across different educational settings, countries and cultural contexts. Similarly, while the regression models yield significant and interpretable coefficients, the explained variance remains modest (R² ≈ 2.75 %). Notably, the intent of this study is not to define a complete set of variables that influence academic performance per se, but to examine whether performance is affected by the interaction between gender and risk and the presence of penalties in assessment tests.

Although it is highly effective in this context, we use a bootstrap simulation based on the assumption of sampling independence and homogeneity. This approach presents the application of our proposed model to a specific instructional unit, providing valuable information through descriptive statistics and regression coefficients tailored to particular groups and specific contexts to support teachers’ decision-making. For example, penalty calibration and risk-free rehearsal quizzes are immediately actionable for most LMSs. Therefore, while the observed effects reflect how one specific cohort might respond to hypothetical assessment design shifts, implementation feasibility and impact may vary across disciplines, class sizes and cultural and educational contexts, warranting site-specific piloting before full adoption.

In addition, we move beyond narratives by framing gender-differentiated responses to penalties as an issue of academic and pedagogical design rather than students’ innate capabilities. This perspective situates assessment policy as a lever for increasing equity in line with SDGs 4 and 5. However, because we did not measure mediating constructs such as test anxiety or stereotype threats, our causal inference regarding why penalties affect genders differently is limited accordingly.

In the same sense, the results should be understood as simulation-based patterns derived from resampling a small, fixed empirical sample. Again, while they suggest consistent trends under varying risk and gender conditions, they do not establish causal relationships or support predictive generalisations beyond the cohort studied.

Conclusion and future researchThis study contributes to the literature by indicating how gender composition and evaluative risk interact to influence classroom-level academic outcomes. The use of a quasi-natural experimental design enriched with bootstrap simulations provides a flexible and replicable framework for exploring how institutional design decisions, such as the use of penalties in multiple-choice assessments, may impact performance. This is possible using different gender configurations and assessment risk levels without altering the original dataset structure and maintaining the original empirical distribution of student capabilities.

In doing so, this study shows that men consistently receive lower grades than women, regardless of the risk environment, which raises concerns and underscores the need to determine the underlying causes. We also examine the interaction between gender and the risk level of exams, finding that scores tend to decrease as the risk level (penalty for incorrect answers) rises, indicating that students become more risk-averse when facing penalties for incorrect answers.

Notably, in terms of gender, we find that the proportion of female students in the class has a notable positive effect on all students’ scores, in which a higher number of women in a classroom elicits a higher average grade. Additionally, the interactive effect between the proportion of women and the risk level is statistically significant. Female students exhibit greater sensitivity to penalty conditions, underscoring the differing risk responses by gender. These results align with the existing literature on students’ risk aversion during exams (Pekkarinen, 2015; Riener & Wagner, 2017; Espinosa & Gardeazabal, 2020; and Montolio & Taberner, 2021) but in a low-stakes context.

The results also suggest that penalties introduce an added difficulty to female students’ academic performance, widening the gender gap. Therefore, a need to develop educational actions that establish more egalitarian and gender-inclusive knowledge assessment environments and performance seems to be warranted, as the impact of gender on academic performance appears to be more significant than that of penalties for incorrect answers in low-stakes exams.

Our application of bootstrapping in this setting reinforces the potential of advanced statistical tools for deriving meaningful insights from constrained data in cohorts. The bootstrap strategy provides a more consistent estimation of the explanatory model, yielding results that align with and complement those in low-stakes scenarios with those of previous studies (Azmat et al., 2016; Hodge et al., 2018; Coffman & Klinowski, 2020; Iriberry & Rey-Biel, 2021; Montolio & Taberner, 2021) but with a significantly smaller volume of data.

Building on these results, future research should pursue several directions to deepen and expand these findings. First, cross-institutional replications can apply the bootstrap framework to heterogeneous cohorts and degree programmes, identifying the courses and conditions under which the gender–risk interaction is most pronounced. Second, longitudinal resilience tracking could follow the same cohort across successive courses to determine whether repeated exposure to risk-adjusted assessments reshapes their risk preferences or academic trajectories. Third, systematic inclusion of richer demographic profiles could help to refine model precision. Finally, examinations of potential psychological moderators that may mediate or moderate penalty effects will further inform the field. These research methods can reveal new instructional strategies for fostering equitable academic outcomes.

FundingThis research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

CRediT authorship contribution statementFrancisco Rabadán: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Rafael Barberá: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Miguel Cuerdo: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Formal analysis, Conceptualization. Luis Miguel Doncel: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

We would like to thank two anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, which have improved the quality of this paper.