This study uses 102 textile enterprises listed in China’s A-share market from 2012 to 2022 as the research objects to explore the impact of artificial intelligence (AI) on enhancing textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Findings reveal that AI can significantly promote textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and this finding holds after a series of robustness tests. The mechanism analysis demonstrates that textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction can be promoted by AI through improving textile raw material suppliers’ total factor productivity, increasing the fixed investment for pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and reducing the price of cotton. Heterogeneity analysis reveals that the positive impact of AI is more significant for textile enterprises with high environmental regulation intensity, executives with digital backgrounds, and intellectual property demonstration cities. In response to these findings, we propose relevant policy suggestions to provide references for accelerating textile enterprises’ transformation and upgrading and promoting steady economic growth.

Since the 18th National Congress of the Communist Party of China, China has made substantive achievements in ecological civilization construction. At the national level, proactive measures have been implemented to establish ecological protection red lines, environmental quality baselines, and resource utilization upper limits. Three major action plans have been rigorously applied to prevent and control air, water, and soil pollution, leading to a continuous enhancement of environmental protection awareness and sustained improvement in ecological environment quality. However, despite significant progress in environmental protection, environmental pollution and climate change challenges remain severe amid rapid industrial and urban development. Among numerous industrial sectors, due to its fundamental, global, and pollution-intensive characteristics, the textile industry has emerged as a critical domain requiring green transformation. This study uses the Chinese textile industry as the research object not only because of its high pollution intensity and substantial emissions reduction pressure but also based on its strategic economic status, industrial chain influence, and urgent need for technological innovation.

As a traditional pillar industry and a significant livelihood industry in China, the textile industry has an irreplaceable strategic position in the national economy. Data show that in 2023, the main business income of enterprises above designated size in China’s textile industry reached 6.2 trillion yuan, accounting for 4.8 % of the national industry. The industry directly and indirectly employs >50 million people, over 60 % of whom are migrant workers from rural areas, serving as a vital force in promoting regional economic development and ensuring livelihood employment. As the world’s largest producer and exporter of textiles, China processes >50 % of the global total fiber volume, and its textile and apparel export volume accounts for more than one-third of the global market, ranking first in the world for 20 consecutive years. The industry’s development is not only related to the stability of industrial and supply chains but also undertakes the important mission of meeting people’s needs for a better standard of living and inheriting excellent traditional culture. However, the pollution and carbon emissions generated in its production process cannot be ignored. According to data released by the International Energy Agency, the total carbon emissions of the textile and apparel industry accounts for 10 % of the global total, making it the second largest source of pollution after the petroleum industry. For every kilogram of fabric produced, 23 kg of carbon dioxide are emitted. Producing one ton of textile products pollutes 200 tons of water, which is a significant factor restricting the industry’s green and sustainable development. If no effective measures are taken, it is expected that the global fashion industry will consume >30 % of the carbon budget by 2050, and as a major textile producer, China will face more severe emissions reduction pressure and challenges from international green trade barriers. Moreover, compared with pollution-intensive industries such as chemicals and steel, the specificity of the textile industry is its wide industrial chain and the environmental relevance of its pollution; from raw material fiber planting, to spinning and weaving, and then treating end-products after disposal, pollution impacts run across the entire life cycle. As a consumer goods industry closely related to residents’ lives, its green transformation is directly related to public health and the practice of sustainable consumption concepts. Therefore, against the backdrop of China’s dual carbon goals and intensifying global green trade barriers, pollution and carbon emissions reduction in the textile industry is not only an environmental governance concern but also a comprehensive proposition for reshaping industrial competitiveness, livelihood well-being protection, and international responsibility.

In recent years, the rapid development of artificial intelligence (AI) technology has provided innovative solutions and new paths for textile enterprises’ transformation and upgrading. With its powerful data processing, analysis, and decision-making capabilities, AI technology can have a significant impact on multiple textile enterprise links, including raw material procurement, production process optimization, wastewater treatment, and waste recycling. By integrating image recognition, machine learning algorithms, and big data analytics technologies, AI can accurately monitor energy consumption and emissions conditions in the production process, conduct intelligent regulation and optimization of production processes, and effectively reduce textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions. AI can also assist enterprises with product design and supply chain management, promoting the entire industry’s development in high-end, intelligent, and green directions. Therefore, an in-depth study of the impact of AI use on the synergistic effect of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction can not only address the industry’s own environmental constraints but also provide a replicable textile sample for advancing traditional manufacturing industries’ green transformation.

Literature reviewBased on existing research on AI and pollution reduction–carbon emissions mitigation, studies have primarily focused on three considerations. First is the indicators for measuring the synergistic effects of AI and pollution–carbon emissions reduction. For AI indicator measurement, a questionnaire survey method was employed by Li et al. (2022) to assess AI levels; Du et al. (2022) used robot density to measure AI indicators, Lin et al. (2024) constructed an AI indicator system and applied the entropy weight method to measure AI intelligence levels, and Xin (2025))) generated an AI dictionary through machine learning from a text analysis perspective, conducting text analyses on listed companies’ annual reports and patents as enterprise-level AI indicators. To measure synergistic indicators of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, Zhang et al. (2025) first calculated carbon dioxide (CO2) and pollutant emissions separately, then used a coupling coordination degree model to compute comprehensive indicators for measuring synergistic effects. Feng et al. (2024) used PM2.5 and CO2 emissions to measure enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions levels, respectively, and determined whether synergistic effects were achieved through regression coefficients.

Second is the impact of AI use and the influence of other variables on pollution–carbon emissions reduction. Regarding AI's effect, Zhao et al. (2024), using data from 74 countries, found that AI can narrow carbon inequality; Zhao et al. (2022) revealed a U-shaped relationship between AI and green total factor productivity (TFP). Huang et al. (2025) demonstrated that AI promotes enterprise energy transition by fostering green technological innovation, strengthening human capital structure, improving environmental information disclosure, and reducing financing constraints. In terms of pollution–carbon emissions reduction, Guo and Yue (2024) found that the digital economy reduces energy intensity at the source, enhances public environmental attractiveness, and improves air pollution and carbon emissions efficiency through terminal treatment. Han et al. (2024) demonstrated that the energy use rights trading system promotes synergistic effects of pollution and carbon emissions reduction by upgrading energy consumption structure and green technological innovation.

Finally, research has examined AI’s impact on pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Zhou et al. (2024) found that AI reduces pollutant emissions intensity by improving energy efficiency and enhancing pollution reduction technologies. Nie et al. (2025) determined that China’s AI innovation development pilot zone policy primarily alleviates environmental pollution by increasing fiscal technology expenditure, improving green technological innovation, and promoting economic agglomeration. Niu (2025) revealed that AI use is correlated with significantly reduced enterprise pollutant emissions, and Cao et al. (2025) found that AI application significantly reduces carbon emissions. Dong et al. (2023) constructed an econometric model using dynamic panel data from 30 provinces to systematically investigate AI’s impact on CO2 emissions and its mechanism, demonstrating that AI significantly reduces CO2 emissions.

While previous studies on AI’s impact on pollution and carbon emissions reduction have been fruitful, some limitations remain. First, the majority of literature has focused on AI’s impact on pollution or carbon emissions reduction individually, with few examining AI’s synergistic effects. Second, existing studies have predominantly analyzed AI’s impact on pollution–carbon emissions reduction from the perspective of all enterprise types, rarely focusing on textile enterprises. Third, most studies have proposed research hypotheses through theoretical analysis, with few deriving the relationship between AI and pollution–carbon emissions reduction using econometric models. Accordingly, this study takes data from 102 listed textile companies in China spanning 2012–2022 as the research object to analyze AI’s impact on the synergistic effects of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. We first construct an indicator system for AI and synergistic of pollution–carbon emissions reduction effects. We then use an econometric model to explore AI’s synergistic effects on textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction.

The theoretical contributions and innovations of this study are as follows. First, it breaks through the limitations of existing literature focusing on all enterprise types, concentrating on the textile industry, constructing an indicator system for AI and synergistic effects on textile enterprises’ pollution–carbon emissions reduction, and deeply exploring the unique mechanism of AI in promoting these synergistic effects. This approach addresses the deficiency of existing research in industry-focused analysis and provides a new perspective for understanding AI’s unique influence on the green transformation of traditional manufacturing. Second, this study transcends the limitations of existing literature by proposing hypotheses through theoretical analysis to examine the internal logical relationship between AI and synergistic pollution–carbon emissions reduction via mathematical models and empirically verify our findings using econometric models, providing a more comprehensive and persuasive analytical framework for follow-up research. The research conclusions provide practical empirical evidence for how textile enterprises use AI to achieve synergistic pollution and carbon emissions reduction effects. For example, we demonstrate that AI promotes such synergistic effects in textile enterprises by improving cotton TFP, increasing fixed investments in pollution–carbon emissions reduction, and reducing cotton prices, providing specific practical directions for applying AI technologies in textile enterprises. Furthermore, the results reveal that AI’s effects vary under different internal and external enterprise environments. This will enable enterprises to formulate more targeted AI application strategies based on actual local conditions to advance pollution–carbon emissions reduction goals and improve economic benefits, promoting the textile industry’s sustainable development.

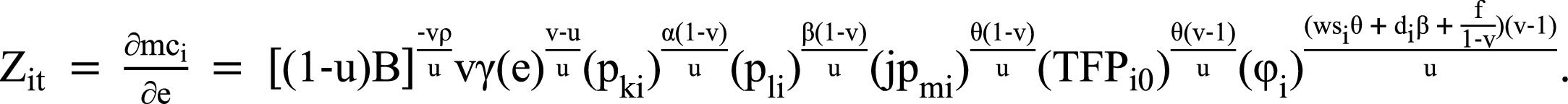

Theoretical analysis and research hypothesesReferencing Forslid et al. (2018), this study integrates AI into the model as a form of intelligent capital. Through expansion, we construct the following theoretical model to explore the impact of AI on coordinating textile industry pollution and carbon emissions reduction.

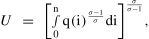

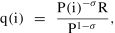

Consumption preferences and market demandWe assume that consumers’ demand for different textile products (i) satisfies the following constant elasticity of substitution (CES) utility function:

where q(i) denotes the quantity demanded of textile i, and σ represents the CES with σ > 1.By applying the utility maximization principle and Lagrangian multiplier method, the demand function for textile i is derived as follows:

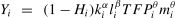

where P(i) signifies the price of textile i, and R is defined as total revenue, with R = ∫0nq(i)×P(i)di.Enterprise productionWe assume that in the process of manufacturing textile products, textile enterprises will simultaneously generate pollutants and CO2. Based on this, we first consider a circumstance in which textile enterprises do not use AI technology when producing textile products. When the production quantity of product Yi is considered, pollutant and CO2 emissions are Zit. When t = 1, it represents pollutant emissions, and when t = 2, it represents CO2 emissions. To reduce enterprises’ pollutant and CO2 emissions, the government will levy pollution and CO2 tax (e), which will motivate textile enterprises to increase the intensity of emissions reduction measures (Hi) to reduce pollutant and CO2 emissions and lower costs. Hi has a value between 0 and 1. When Hi is close to 0, it indicates that the enterprise has barely implemented any emissions reduction measures. If Hi approaches 1, the enterprise can allocate more resources to production. Then, based on the given TFP and production factor input, the enterprise can produce a relatively large number of products. Conversely, when Hi is close to 1, it indicates that the enterprise has invested a large amount of resources in pollution emissions reduction, and Hi will approach 0, resulting in reduced resources for enterprises’ production, which reduces product output. Based on this, by referring to the approach of Forslid et al. (2018), the production function of the textile enterprise for this textile product and the functions of pollutant and CO2 emissions can be respectively expressed as follows:

where TFPiθ represents the TFP of the upstream textile industry chain (the textile raw material suppliers), and mi represents the textile raw material suppliers’ factor input. Then, the raw material input of textile product i is the product of the TFP of its upstream raw material suppliers and the factor input miθ×TFPiθ. ϖ(Hi,fci) represents the function of the textile enterprise’s pollutant and CO2 emissions reduction, where fci represents the textile enterprise’s fixed investment for reducing pollutant and CO2 emissions; fci > 0,ki represents the textile enterprise’s capital input; li represents the textile enterprise’s labor input; and α, β, and θ respectively represent the shares of the enterprise’s capital, labor, and raw material input, which are all greater than zero and less than one. Textile raw materials demand is primarily determined by prices. Consequently, textile raw material suppliers’ input is correlated with raw material prices. This relationship can be further formalized as mi = jpmi, where pmi denotes the price of textile raw material i, and j represents the input price elasticity coefficient for raw materials. This coefficient measures the sensitivity of raw material input quantities to changes in prices.Introducing AI into production technologyThen, we consider textile enterprises introducing AI technology into production processes. First, the relationship between AI and labor is defined as li = li0φidi, where φi is the textile enterprise’s AI level, li0 is the initial labor input, and di is the substitution coefficient of AI for labor input. Since ∂li∂φi=dili0φidi−1 < 0, di < 0. In addition, Choi et al. (2024) and Huang et al. (2018), demonstrated that AI can replace the enterprise’s labor force. Therefore, we assume that a negative relationship exists between textile enterprises’ application of AI and labor input that is, ∂li∂φi < 0. Second, a connection is established between textile enterprises’ AI and textile raw material suppliers’ TFP from the perspective of technological spillover. When textile enterprises apply AI technology, we expect this to have a technological spillover effect on upstream cotton suppliers through technological exchange and collaborative research and development (R&D). For example, after textile enterprises use AI to optimize the production process, they may share some optimization experiences and technologies with suppliers, enabling them to improve planting technologies, production management, and other processes and improving the suppliers’ TFP. The relationship between textile enterprises’ AI and raw material suppliers’ TFP is defined as TFPi = TFPiθφiwsiθ, where φi is the textile enterprise’s AI level, TFPi0 is the raw material suppliers’ TFP, si is the AI enhancement coefficient for the raw material suppliers’ TFP, and W is the technological spillover intensity coefficient, which measures the degree of technological spillover of the textile enterprise’s AI application to upstream suppliers, with a value range of [0,1]. A larger value indicates a stronger technological spillover effect. Previous research (Zhong et al., 2024) has demonstrated that AI can improve TFP. Therefore, we assume that a positive relationship exists between the textile enterprise’s application of AI and the TFP of cotton; that is, ∂TFP∂φ>0. Since ∂TFPi∂φi=wsiθTFPi0φiwsiθ−1>0, 0 < si. To make ∂2TFPi∂2φi=(wsiθ−1),wsiθφiwsiθ−2 < 0 and maximize the TFP value, therefore si < 1. In conclusion, 0 < si < 1. Finally, in the traditional raw material textile market, information asymmetry is a common problem. Market participants such as farmers, middlemen, and textile enterprises often find it difficult to fully grasp information such as market supply and demand and price trends, which increases the uncertainty and risk of market decisions. AI technologies such as big data analytics, the Internet of Things, and blockchain can collect, process, and analyze real-time market data, predict future textile raw material market supply and demand trends, provide more accurate and comprehensive market information for market participants, reduce information asymmetry, and provide valuable insights to support evidence-based planting and sales strategies for farmers and textile enterprises. This can optimize resource allocation and avoid price fluctuations and resource waste caused by indiscriminate planting and excessive competition. Furthermore, through precision agricultural management, AI can enable farmers to achieve operations such as precision irrigation and fertilization, increase textile raw materials’ output and quality, and further reduce materials’ production costs and the market price. Therefore, we assume that a negative relationship exists between textile enterprises’ AI application and textile raw materials’ price; that is, ∂pmi∂φi < 0.

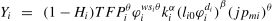

We refer to Prettner (2019), incorporating AI into the production function and the functions of pollutant and CO2 emissions, and incorporating the relationships between AI and labor input, as well as between AI and TFP into the production function of textile enterprises’ cotton textile products and the functions of pollutant and CO2 emissions. Therefore, the production function and the functions of pollutant and CO2 emissions incorporating the role of AI can be obtained as follows:

As shown in Eq. (6), textile enterprises’ pollutant and CO2 emissions are not only determined by their production and operation activities but also by their practices for reducing pollutants and CO2. Considering the impact of AI on textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction, referencing Forslid et al. (2018), the following enterprise functions for pollution and carbon emissions reduction are further obtained:ϖ(Hi,φi,fci)=[(1−Hi)/φif]1vh(fci), where 0 < v < 1, 0≤Hi<1. According to the suggestion of Forslid et al. (2018), h(fci)=fciρ=(ρ>>0) is specified as the fixed investment function of the enterprise for pollution reduction and carbon emission reduction and ∂h(fci)∂fci > 0, fci represents the fixed investment of the textile enterprise for reducing the emissions of pollutants and carbon dioxide and fci > > 0, f is the optimal input coefficient of AI and 0 < f< < 1. As the textile enterprise’s fixed investment for reducing pollutant and CO2 emissions increases, its emissions will decrease accordingly, which can be expressed as ∂ϖ(Hi,φi,fci)∂fci < 0. By combining the above equations, the textile enterprise products’ production function can be derived as follows:

According to the principle of profit maximization, there should be ∂Yi∂φi>0,∂2Yi∂2φi< 0. From this, according to Eq. (7), 0 < wsiθ+diβ+f1−v < 1 can be obtained. From an economic perspective, Eq. (7) also implies that textile enterprises’ pollutant and CO2 emissions have a dual influence as the output and the input required for production. The enterprise’s input factors include capital, labor, raw materials, pollutants, and CO2. According to the research of Forslid et al. (2018), based on the principle of cost minimization, the textile enterprise’s cost function is derived as follows:

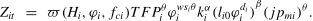

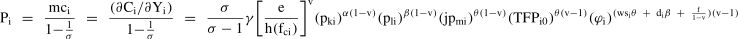

where since∂Ci∂TFPi0 and ∂Ci∂φi should be <0, in the cost function, the exponents of TFPi0 and φi should be <0; that is, the exponents of both are v − 1. γ represents a constant, fci represents the fixed investment made by the textile enterprise to reduce pollutant and CO2 emissions, Pki represents the capital cost, Pli represents the wage, e represents the cost related to textile enterprises’ pollutant and CO2 emissions.Solving for the equilibrium of the textile marketUnder the CES demand function, according to the markup pricing principle of enterprises, we calculate the product sales price that maximizes textile enterprises’ profit, where mci is the marginal cost as follows:

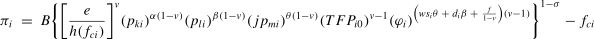

Combining the demand function in Eq. (2) with the product sales price function in Eq. (9), referring to Forslid et al. (2018), we derive textile enterprises’ profit function as follows:

where B≡γ1−σσ−σ(σ−1)σ−1Rp1−σ. Following Forslid et al. (2018), we specify h(fci)=fciρ(ρ<0) as the enterprise’s fixed investment for pollution and carbon emissions reduction. By considering the company’s profit maximization, we can determine the optimal investment strategy for mitigating pollutant and CO2 emissions. When maximizing textile enterprises’ profit, taking the partial derivative of Eq. (10) with respect to fci, the optimal amount of the enterprise’s fixed investment can be obtained as follows:where u = 1 − vρ(σ−1). Since fci when u > 0 is smaller than fci when u 〈 0, according to the profit maximization principle, it can be concluded that u 〉 0. In addition, considering that the textile enterprises’ fixed investment for reducing pollution and CO2 emissions cannot be negative, u < 1, and we get 0 < u < 1. As shown in Eq. (11), with textile enterprises’ AI improvement, the fixed investment to reduce pollution and CO2 emissions rises.The relationship between AI and pollutant and CO2 emissions intensity is further considered. According to the cost function in Eq. (8), using Shephard’s lemma, taking the partial derivative of the textile enterprise’s price (e) for pollutant and CO2 emissions, and substituting u = 1 − vρ(σ−1) into it, the intensity of pollutant and carbon dioxide emissions of textile enterprises can be derived as follows:

Since textile enterprises’ pollution and CO2 emissions intensity cannot be negative, λit cannot be less than zero. Eq. (12) implies that this intensity is related to the price of textile raw materials, textile raw material suppliers’ TFP, and textile enterprises’ fixed investment in pollutant and CO2 emissions reduction equipment.

Impact mechanism of AI on textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reductionTaking the partial derivative of Eq. (12) with respect to AI (φi) gives ∂Zit∂φi<0. The negative partial derivative clearly demonstrates that AI reduces textile enterprises’ pollutant and CO2 emissions intensity. Therefore, we propose the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 1. Introducing AI can help textile enterprises reduce pollutant and CO2 emissions intensity; that is, AI can promote textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction.

Taking the partial derivative of Eq. (12) with respect to cotton of textile enterprises’ TFP gives ∂Zit∂TFPi0<0. The equation indicates that an increase in textile raw material suppliers’ TFP will decrease textile enterprises’ pollution and CO2 emissions intensity. From the previous conclusion, textile enterprises’ AI application has a positive impact on textile raw material suppliers’ TFP; that is, ∂TFPi0∂φi>0. Since ∂Zit∂φi=∂Zi∂TFPi0∂TFPi0∂φi<0, we can infer that AI reduces textile enterprises’ pollution and CO2 emissions intensity by increasing the TFP of textile raw material suppliers.

In addition, Eq. (11) indicates that the use of AI helps to increase the level of fixed investment for reducing pollutant and CO2 emissions; that is, ∂fci∂φi>0. Combining Eq. (7), reveals that increased fixed investment will decrease pollution and CO2 emissions intensity; that is, ∂Zit∂fci=∂Zit∂ϖ(Hi,φi,fci)∂ϖ(Hi,φi,fci)∂fci < 0. Since ∂Zit∂φi=∂Zi∂fci∂fci∂φi<0, we can infer that the use of AI will reduce textile enterprises’ pollution and CO2 emissions intensity, increasing the fixed investment for reducing emissions.

Taking the partial derivative of Eq. (12) with respect to cotton of textile enterprises’ price gives ∂Zit∂pmi>0. The equation indicates that an increase in textile raw materials price will increase textile enterprises’ pollution and CO2 emissions intensity. From the previous conclusion, AI has a negative impact on textile raw materials price; that is, ∂pmi∂φi<0. Since ∂Zit∂φi=∂Zi∂pmi∂pmi∂φi<0, we can infer that AI reduces textile enterprises’ pollution and CO2 emissions intensity by reducing the price of textile raw materials. Based on the above discussion, we propose the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 2a. AI promotes textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction by increasing textile raw material suppliers’ TFP.

Hypothesis 2b AI promotes textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction by increasing the fixed investment for reducing pollution and CO2.

Hypothesis 2c. AI promotes textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction by reducing the price of textile raw materials.

This study refers to the approach of Xin (2025)), using 73 keywords such as “AI” and employing Python text analysis to mine the text of listed textile companies’ annual reports from 2012 to 2022. We obtain the word frequencies of each AI keyword, and after summing up and counting each keyword for each company, one is added to the sum and then take the logarithm to obtain listed companies’ AI index.

Explanatory variable: synergistic efficiency of pollution and carbon emissions reduction (Syeff)We adopt the approach proposed by Zhang et al. (2025). To quantify the synergistic level of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, we first subject the CO2 and pollutant emissions to negative standardization. Then, we employ a coupling coordination degree model to calculate their coupling coordination degree. Finally, we use the coupling coordination degree to measure the synergistic effects of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Due to the negative standardization of the data, a larger coupling coordination degree signifies stronger synergy of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. First, we separately construct indicators for CO2 and pollutant emissions. The coupling coordination model is then used to calculate the coupling coordination degree, with the calculations for the two emission metrics outlined as follows. CO2 emissions (Cde): Referencing Shen et al. (2025), we use the following formula to calculate enterprises’ CO2 emissions:

Carbon dioxide emissions = (enterprises’ main business cost/industry’s main business cost) × industry’s total energy consumption × CO2 conversion coefficient, where the carbon dioxide conversion coefficient is 2.493.

Pollutant emissions (Pe): Referencing Le et al. (2022), we use five pollutant indicators to measure enterprise pollution emissions, encompassing emissions of chemical oxygen demand, ammonia nitrogen, sulfur dioxide, nitrogen oxides, and smoke and dust emissions. First, we standardize these five pollutant matrices, then calculate their respective adjustment coefficients to produce the comprehensive index of the five pollutants’ emissions.

Mediating variablesTextile raw material suppliers’ of TFP: A higher TFP indicates stronger production capacity and supply stability, and that long-term and stable cooperative relationships can be formed with textile enterprises more easily. Textile enterprises continuously classify such suppliers as core suppliers (among their top five suppliers), and the proportion of procurement volume accounted for by these suppliers does not fluctuate significantly, which avoids the costs associated with frequent supplier replacement. Therefore, given the availability of data, we construct a proxy indicator for textile raw material suppliers’ TFP using a combination of the depth of cooperation between textile enterprises and their core suppliers + procurement concentration, using the following specific calculation method:

where CCyearijt denotes the number of consecutive years of cooperation between textile enterprise i and a particular top five supplier j in year t. The number of consecutive years of cooperation for a supplier is calculated as follows. If supplier j appears in the top five raw material suppliers of textile enterprise i for k consecutive years, then CCyearijt equals k (e.g., if supplier j appears consecutively from 2012 to 2015, CCyearijt is 4). If supplier j appears only in the current year, CCyearijt is 1. PPAijt represents the proportion of procurement volume from a particular top five supplier j in year t to textile enterprise i’s total annual raw material procurement volume.Fixed investment for pollution and carbon emissions reduction (PCFI): Considering data availability, this study follows Luo et al. (2025), using textile enterprises’ environmental protection investment to measure the enterprises’ fixed investment in pollution and carbon emissions reduction.

Price of textile raw materials (CP): In view of data availability and the types of textile raw materials, we use the price of cotton to represent the price of textile raw materials. We convert the average selling price of 50 kg of cotton in 12 provinces from the Compilation of National Agricultural Product Cost and Benefit Data into the average selling price per kilogram of cotton to measure the price of cotton.

Control variablesReferencing existing literature (Gu et al., 2022; Wang et al., 2023), this study introduces the following control variables into the model. Enterprise age (Age), which is measured by subtracting the listing year from the current year; the proportion of independent directors (Indep), which is measured by the ratio of the number of independent directors to the size of the board of directors; asset scale (Size), which is measured by the natural logarithm of the total assets; net profit rate on total assets (Roa), which is measured by the ratio of the net profit to the average balance of total assets; and proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder (Share), which is measured by the proportion of shares held by the largest shareholder.

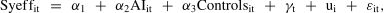

Model constructionBenchmark regression modelTo verify the impact of AI on textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, we construct the following regression model:

where i represents the enterprise, and t represents the year. Syeffit denotes the coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, AIit represents the enterprise’s AI level, and Controlsit represents the control variables. γt, ui, and εit are the time fixed effect (FE), individual FE, and the random disturbance term, respectively.Mediating effect modelTo examine the mediating effects of TFP, fixed investment in pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and factor input structure, we construct a mediating effect model building the following model based on Model (13), following the methodologies proposed by Xie et al. (2024) and Li et al. (2025):

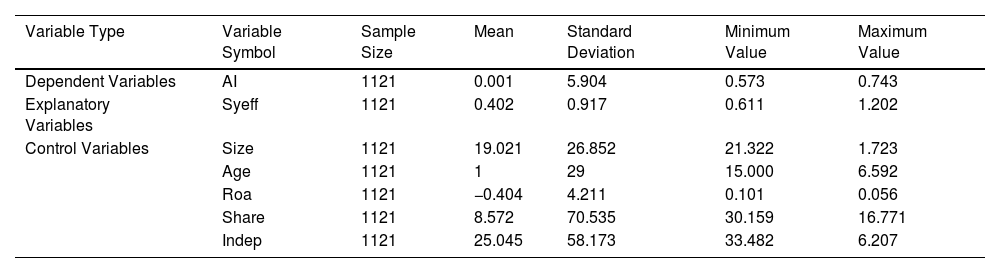

where Mit represents the mediating variables of cotton TFP, the fixed investment for pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and the price of cotton, and other variables are the same as those in Eq. (14).Data sources and descriptive statisticsThis study takes the panel data from A-share listed textile companies from 2012 to 2022 as the initial sample. Referencing Xu et al. (2023) and Zhu et al. (2022), we define enterprises in industries such as chemical fiber manufacturing; textiles; garments; leather, fur, feather, and its products; and shoemaking as textile enterprises. Using the aggregated data in the Compilation of National Agricultural Product Cost and Benefit Data, considering data availability, this study selects textile enterprises in 12 major cotton-producing provinces in China as the research objects, encompassing Hebei, Shanxi, Jiangsu, Anhui, Jiangxi, Shandong, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Shaanxi, Gansu, and Xinjiang. We then screened the initial data according to five requirements. 1. Exclude all listed financial companies; 2. exclude companies under special treatment (ST, *ST, and PT); 3. winsorize continuous variables at the 1 % and 99 % levels; 4. exclude companies with serious missing relevant data samples; and 5. exclude companies whose industries have changed during the research period. Applying these steps yields a total of 102 companies and 1121 firm–year observations. Data are obtained from the Sina Finance website, the China City Statistical Yearbook, the China Electric Power Yearbook, the China Energy Statistical Yearbook, the China Industrial Statistical Yearbook, the China Stock Market & Accounting Research database, the Wind database, and the Compilation of National Agricultural Product Cost and Benefit Data. The data are mainly processed using Stata 15. Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the variables.

Descriptive statistics.

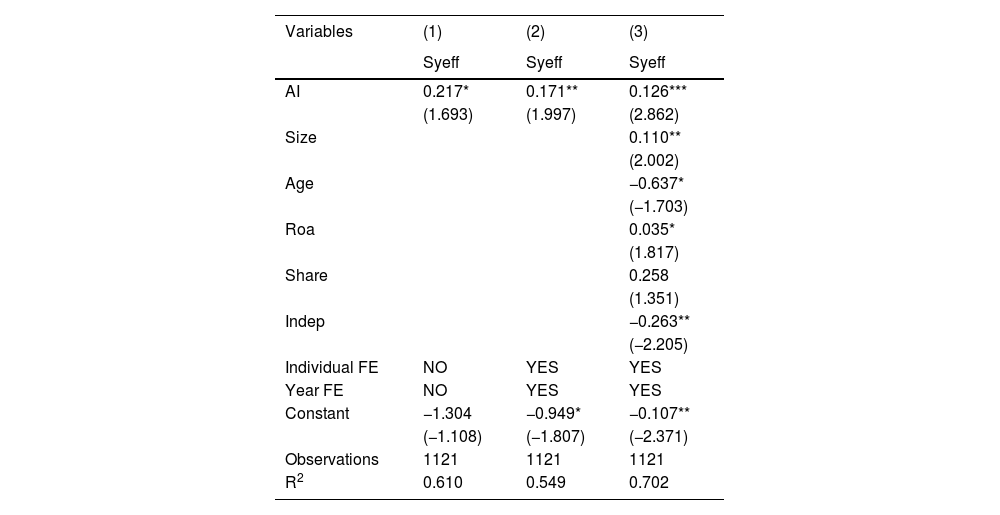

We use Model (14) to test the impact of AI on textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Table 2 presents the regression results. Column (1) does not include control or FE variables, Column (2) introduces individual and time FEs, and Column (3) adds control variables. The regression results reveal that the coefficients of AI in Columns (1)–(3) are all significantly positive at least at the 10% level, indicating that AI can enable textile enterprises to achieve the coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, reducing textile enterprises’ of pollutant and CO2 emissions, verifying Hypothesis 1.

Benchmark regression.

Note: t-values are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1 %, 5 %, and 10% levels, respectively.

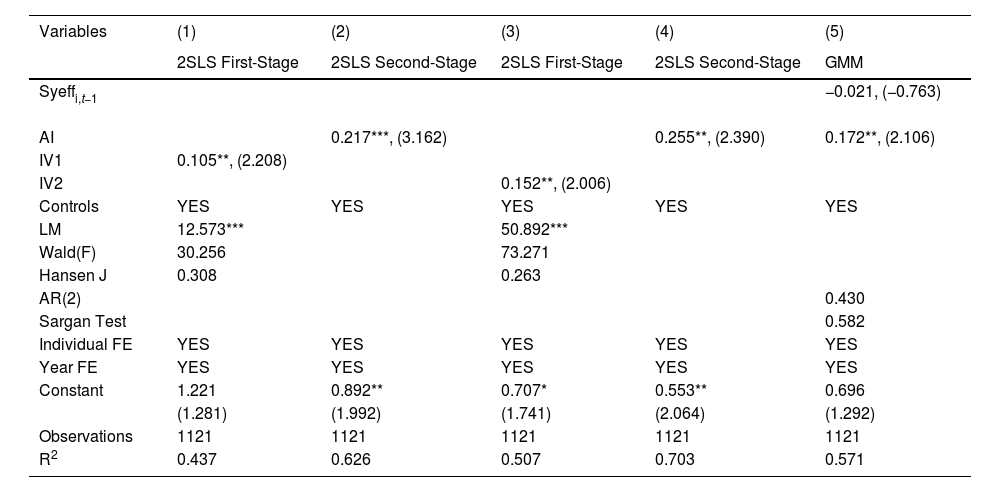

We employ the instrumental variable (IV) two-stage least squares (2SLS) approach to address potential endogeneity. Two IVs are constructed as follows. IV1 is the average number of industrial robot installations in other countries. We use the average number of industrial robot installations in five countries (the United States (US), Switzerland, Germany, Japan, and Brazil) as the IV. In the global AI field, developed countries such as the US and those in Europe have consistently maintained a leading position in technology. These countries have significant advantages in basic theories, core technologies, and high-end AI human resources, and have a significant influence on the development direction and technical standards of global AI. As a late-comer, China’s AI development is inevitably affected by these countries’ technological development in the process of catching up and surpassing existing capabilities. Therefore, the average number of industrial robot installations in other countries as an IV satisfies the relevance condition. Furthermore, the average number of industrial robot installations in other countries has no obvious impact on the pollution and carbon emissions reduction synergy of China’s textile industry. Therefore, the average number of industrial robot installations in other countries meets the IV exogeneity requirement. The second instrumental variable is policy enactment (IV2). The development of AI cannot be separated from the support of relevant AI policies. China’s New Generation AI Development Plan enacted in 2017 provides a fitting quasi-natural experiment for examining the impact of AI on textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction. We consider enterprises in the years 2017 and after as the experimental group, and the years before 2017 as the control group using a dummy variable. Considering the possible lag in the impact of the New Generation AI Development Plan strategy on pollution and carbon emissions reduction, we use a one-period lag of the dummy variable as IV2. We perform the regression using Model (14). Columns (1) and (2) of Table 3 present the regression results of the IV1, and columns (3) and (4) present the regression results for IV2. The LM statistics for the two IVs are both significant at the 1 % level, rejecting the null hypothesis of insufficient IV identification. The Wald F-values of the two IVs are greater than the critical value of 16.38 at the 10 % significance level, rejecting the null hypothesis of weak IVs. Moreover, the Hansen J test yields p-values for both IVs that exceed 0.1, once again satisfying the IV overidentification test. Therefore, the selected IVs are reasonable. At the same time, the second-stage regression results reveal that the coefficients of AI for the two IVs are both significantly positive at least at the 5 % level, which is consistent with the baseline conclusions, verifying robustness.

Endogeneity regressions.

Note: t-values are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively.

To further address endogeneity concerns stemming from potential time-dependent effects that could lead to omitted variable bias in which a firm’s current level of synergistic pollution and carbon reduction may be influenced by its past performance in these areas, this study employs the system generalized method of moments (GMM). We introduce a one-period lag of the synergistic pollution–carbon reduction indicator into the benchmark regression model to alleviate such endogeneity. The results reveal that AR(2) and the Sargan test values are both greater than 0.1, indicating no serial correlation in the random disturbance term of the model, and the model passes the overidentification test. Therefore, system GMM is a suitable approach. The results in Column (5) of Table 3 show that the coefficient of AI is significantly positive at the 5 % level, which is consistent with the baseline conclusions, indicating robustness.

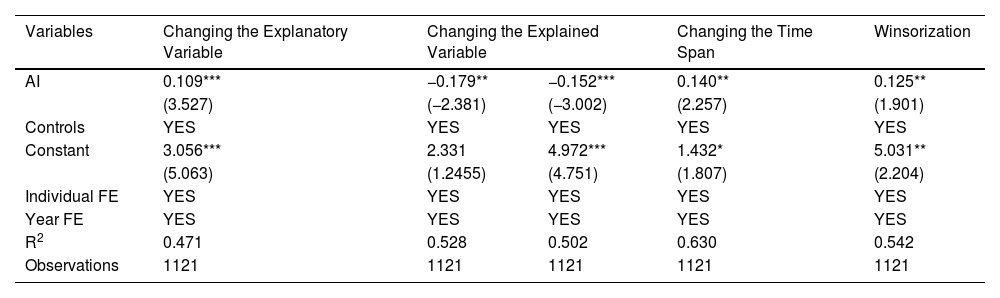

Robustness testsTo ensure the robustness of the benchmark results, we conduct four robustness tests. In the first method, we replace the explanatory variable’s measurement method with the natural logarithm of the listed company’s number of AI patent applications in the current year plus one to remeasure enterprises’ AI level. In the second method, we change the explained variable measurement to the enterprise’s pollutant and CO2 emissions. If the coefficients of AI in both regressions are found to be significantly negative, this will indicate the coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. In the third method, we alter the time span of the research sample to avoid the interference of the COVID-19 pandemic on the results by excluding samples from 2020 to 2022, adjusting the time span of the sample from 2012 to 2022 to 2012–2019. In the fourth method, we winsorize all continuous variables at the 1 % level to reduce the interference of outliers on the research results. The results in Table 4 confirm that the AI variable in the first, third, and fourth methods is significantly positive at least at the 5 % level, and is significantly negative at least at the 5 % level for the second method. This indicates that AI facilitates the coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction, which is consistent with the benchmark research conclusions and confirms robustness.

Robustness tests.

Note: t-values are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively.

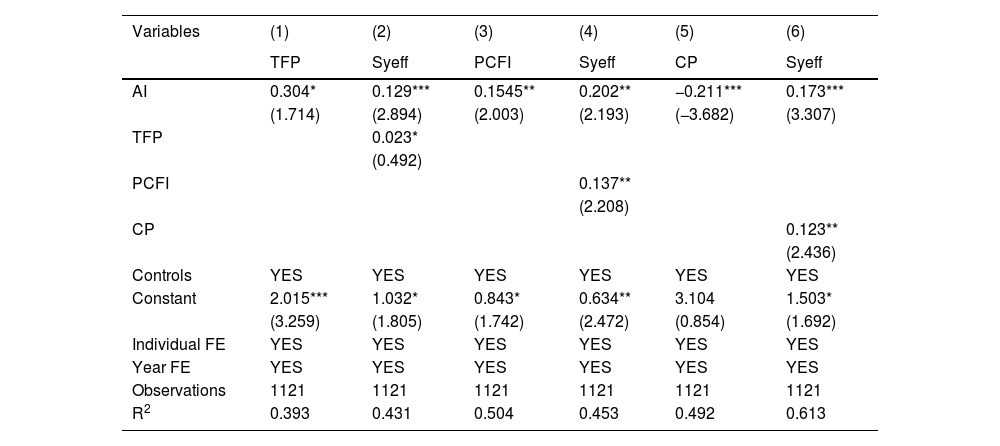

The benchmark regression results demonstrate that AI facilitates the coordinated enhancement of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Based on Models (15) and (16), we next conduct the mediating effect tests. The results in Table 5 reveal that the coefficients of AI in Columns (1) and (3) are both significantly positive, indicating that AI can increase textile raw material suppliers’ TFP and fixed investment for pollution and carbon emissions reduction. The coefficient of AI in Column (5) is significantly negative, indicating that AI can reduce the price of cotton. Furthermore, the coefficients of AI in Columns (2), (4), and (6) are also significantly positive. Therefore, we can conclude that AI promotes textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction by increasing textile raw material suppliers’ TFP, increasing the fixed investment for pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and reducing the price of cotton. Therefore, Hypotheses 2a–2c are verified.

Mediating effect tests.

Note: t-values are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively.

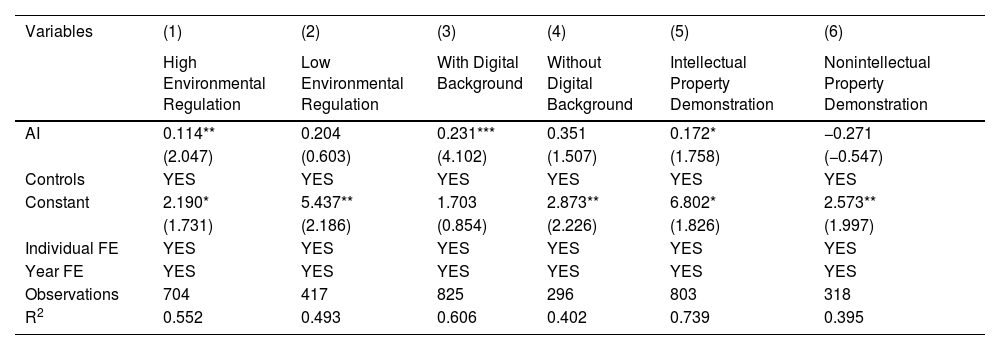

Zhang et al. (2024) found that different environmental regulation intensity has heterogeneous effects on the extent of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Accordingly, following Kou et al. (2024), we employ the entropy weight method to measure the environmental regulation intensity of the cities where enterprises are located. We divide the sample using the average environmental regulation intensity value as the benchmark, where enterprises situated in cities with environmental regulation intensity above the average are categorized as high environmental regulation intensity enterprises and assigned a value of 1, and those in cities with environmental regulation intensity below the average are classified as low environmental regulation intensity enterprises and assigned a value of zero. The results in Table 6 reveal that AI has a significantly positive impact on the coordinated enhancement of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction in cities with high environmental regulation intensity, while it has no significant impact on textile enterprises in cities with low environmental regulation intensity. This may be because governments in regions with strong environmental regulation usually implement strict environmental protection laws, regulations, and standards, and impose strict supervision and restrictions on textile enterprises’ pollutant emissions. Therefore, textile enterprises face greater compliance pressure, which compels them to seek more environmentally friendly and efficient production methods and technical means to meet regulatory requirements such as AI. The use of AI enables textile enterprises to control the production process, optimize resource utilization, and reduce pollutant emissions more precisely. At the same time, the public in regions with strict environmental regulations usually has a stronger awareness of environmental protection and a greater demand for green products. To meet market demand and enhance the brand image, enterprises are more inclined to adopt technologies such as AI to reduce environmental pollution during the production process. In regions with lax environmental regulations enterprises may not have sufficient motivation to invest in expensive AI technology, due to the high initial investment cost of AI technology and the lack of corresponding policy incentives and regulatory pressure. Enterprises in such regions may consider production through traditional methods to be less costly, resulting in the insignificant impact of AI on reducing emissions in regions with low environmental regulation intensity.

Heterogeneity analysis.

Note: t-values are in parentheses. ***, **, and * indicate significance at 1 %, 5 %, and 10 % levels, respectively.

As senior enterprise managers, executives are responsible for formulating enterprises’ strategic directions and making decisions. Their background characteristics, e.g., educational experience, work experience, and professional knowledge, will directly affect their judgment of external environments such as market trends, technological innovations, and competition, influencing enterprises’ strategic choices and decision-making quality. Therefore, we surmise that executives with a digital background will have an impact on enterprises’ AI development, and further affect textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction. This study references Yu et al. (2025), constructing an indicator for executives’ digital backgrounds to conduct grouped regression. For enterprises where executives hold digital backgrounds, this variable is assigned a value of 1, otherwise it is assigned a value of zero. The results in Table 6 reveal that AI has a significantly positive impact on textile enterprises’ coordinated enhancement of pollution and carbon emissions reduction when executives have a digital background, while it has no significant impact on enterprises with executives who do not have a digital background. This may be because textile enterprises with executives that have a digital background often have a deeper understanding and higher acceptance of emerging technologies. They understand the significance of digital and intelligent transformation for advancing enterprises’ operations efficiency, cost control, and sustainable development. This background makes enterprises more proactive in promoting AI technology applications. By using AI technology, textile enterprises can monitor real-time energy consumption and pollutant emissions in the production process. Through big data analytics and machine learning algorithms, such systems can identify production links with high energy consumption and high emissions, automatically adjust production parameters, and optimize the production process, reducing energy consumption and pollutant emissions. In textile enterprises where executives do not have a digital background, their awareness and understanding of emerging technologies are limited. They may not fully recognize the significance of digital transformation and intelligent upgrading for sustainable development, and lack the enthusiasm and initiative for promoting AI technology application. Furthermore, due to the lack of digital thinking, such enterprises may find it difficult to effectively combine AI technology with actual business scenarios, and may simply introduce some intelligent devices or systems without establishing a complete intelligent solution. This disconnection between technology and business will prevent the potential of AI technology from being fully realized, resulting in the insignificant impact of AI on pollution and carbon emissions reduction.

Intellectual property protection heterogeneityZhou et al. (2025) demonstrated that intellectual property protection (IPP) significantly incentivizes enterprises to increase R&D investment while also facilitating green technological innovation, and varying IPP intensities may have heterogeneous impacts on pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Following the approach of Cheng et al. (2024), we conduct grouped regressions based on whether the city where an enterprise is located is designated as a National Intellectual Property Demonstration City in the corresponding year. If the city is designated as a demonstration city, this variable is assigned a value of 1, otherwise it is assigned a value of zero. The results in Table 6 reveal that AI significantly enhances the synergistic effects of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction in pilot cities, whereas this effect is insignificant for textile enterprises in nonpilot cities. This discrepancy can be attributed to the national IP pilot and demonstration cities serving as typical carriers for the optimizing institutional environments—their strength of IPP, supporting innovation policies, and technology transfer service systems directly influence the effectiveness of AI in facilitating textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Theoretically, the more robust the institutional environment in these cities yields greater stability and effectiveness with which textile enterprises can apply AI to achieve pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and the stronger the enterprises’ motivation and capacity to invest in AI technologies to optimize environmental governance processes. Specifically, the institutional advantages of national IP pilot and demonstration cities provide support for AI to empower textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction in at least two ways. First, government authorities in these cities typically establish more robust IPP mechanisms and innovation incentive policies. By strengthening IPP for AI technological achievements, cities reduce the risk of infringement when textile enterprises adopt technologies such as AI monitoring systems, intelligent pollution discharge equipment, and low-carbon production scheduling algorithms, safeguarding the long-term returns on enterprises’ technological investments. Furthermore, governments can assist textile enterprises in addressing AI application challenges (e.g., technological compatibility issues and high initial investment costs) by providing technology matching platforms and special subsidies, and streamlining environmental approval processes to facilitate enterprises’ access to AI technical resources and supportive services required for pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Second, with China’s deep integration of the dual carbon goals and the concept of green development into industrial transformation, the innovation-oriented institutional atmosphere in national IP pilot and demonstration cities guides textile enterprises to develop a deeper understanding of macroenvironmental policy requirements and green market competition trends. This encourages enterprises to integrate AI technology application with their for pollution and carbon emissions reduction responsibilities. Using AI, enterprises can achieve real-time traceability of pollutant emissions and dynamic optimization of production energy consumption, transforming environmental governance needs into voluntary technological upgrading initiatives and proactively enhancing their green production capabilities and environmental performance. Therefore, the promotional effect of AI on pollution and carbon emissions reduction is more pronounced for textile enterprises in national IP pilot and demonstration cities, effectively reducing enterprises’ pollutant emissions and carbon footprints while increasing overall pollution and carbon emissions reduction. In contrast, shortcomings in the institutional environments of non-national IP pilot and demonstration cities limit the effectiveness of AI in empowering textile enterprises to reduce pollution and carbon emissions. Weaker IPP in such cities exposes textile enterprises to higher risks of technology leaks and counterfeiting of AI-related achievements when applying AI technologies, which reduces enterprises’ willingness to invest in AI. In addition, supportive services (e.g., government-provided technical support and policy subsidies) are relatively scarce in nonpilot cities, and textile enterprises struggle to bear the high costs associated with AI equipment procurement, technology R&D, and personnel training, and lack guidance for accurately aligning AI technologies with existing pollution and carbon emissions reduction needs, preventing AI from fully exerting its effectiveness in environmental governance. Furthermore, textile enterprises in nonpilot and nondemonstration cities often prioritize short-term production efficiency and have insufficient awareness of the long-term value of pollution and carbon emission reduction, which further weakens their initiative to optimize environmental governance through AI technologies.

Conclusions and policy recommendationsConclusionsThis study uses panel data from 102 Chinese textile enterprises spanning 2012–2022 as its research object to examine the impact of AI on the synergistic effects of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction. The main research findings are threefold. First, AI significantly promotes the synergistic effects of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Second, AI facilitates these synergistic effects through mechanisms of improving textile raw material suppliers’ TFP, increasing fixed investment allocated to pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and lowering cotton prices. Third, the positive impact of AI on the synergistic effects of pollution and carbon emissions reduction is more pronounced for enterprises in cities characterized by high environmental regulation intensity, with executives that have digital backgrounds, and those located in IP demonstration cities.

Policy recommendationsBased on our results, we propose four policy recommendations. First, the government should introduce relevant policies to reduce enterprises’ technological transformation costs through means such as tax exemptions, tax reductions, and financial subsidies, and encourage textile enterprises to purchase and install intelligent environmental protection equipment with AI technology. Policymakers should also support textile enterprises’ R&D and AI technology innovation, promoting and facilitating industry–university–research collaborations. Jointly conducting technological R&D and innovation activities can promote AI technology application and development for pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Furthermore, a group of representative textile enterprises should be chosen as demonstration points to showcase the practical application effects of AI technology in pollution and carbon emissions reduction. Case sharing and on-site observation can stimulate the enthusiasm of more enterprises to participate in AI application and development. Textile enterprises, for their part, should optimize factor input structures, increase fixed investments in pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and actively embrace AI technology. By introducing advanced AI equipment and systems, strengthening internal R&D capabilities, and monitoring the cotton market, textile enterprises can optimize the production process and improve production efficiency, reducing pollutant and CO2 emissions.

Second, the government should strengthen environmental supervision and regulatory enforcement efforts to ensure that textile enterprises strictly comply with environmental protection laws and standards. For enterprises with low environmental regulation intensity, the government should increase supervision and urge them to improve their environmental protection standards and technology levels. Severe penalties should be imposed on enterprises that commit environmental violations in accordance with the law.

Third, when selecting and training executives, textile enterprises should prioritize cultivating and improving their digital background and capabilities. Enterprises should encourage executives to participate in relevant training and learning activities to improve their AI technology understanding and application capabilities. For existing executives in enterprises without digital backgrounds, efforts should be made to strengthen digital transformation and talent cultivation to enhance enterprises’ digital capabilities.

Fourth, the government should further improve the IPP system and increase regulatory oversight of intellectual property infringement to provide a strong guarantee for textile enterprises’ innovative development. Enterprises should establish and improve IPP systems, strengthen core technology and innovation achievement protection, and enhance core competitiveness. Furthermore, enterprises should actively participate in developing industry standards and norms to promote the entire industry’s technological progress and innovative development.

Limitations and future research directionsIn contrast to previous research, this study focuses specifically on textile enterprises. The findings are derived using mathematical models and validated using econometric models, whereas the findings of existing studies were primarily proposed through theoretical analysis and applied to enterprises across all industries. Nevertheless, this study still has two notable limitations. (1) Due to data availability constraints, the indicators in this study may not be sufficiently comprehensive. (2) With a time span covering 2012 to 2022, the study cannot effectively assess long-term effects.

Future research can be expanded in the following directions. (1) Optimize the indicator system and employ other more robust methods for indicator construction. (2) Since this study focuses on Chinese textile enterprises, future research can further expand the scope to more subsectors and different countries to compare differences in the impact of AI on the synergistic effects of pollution and carbon emissions reduction across sectors and nations. (3) As this study only explores a subset of the underlying mechanisms, future research can conduct in-depth investigations into the dynamic mechanisms through which AI promotes the synergistic effects of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction, and identify more potential mediating and moderating variables. (4) In line with current technological developments, future research can examine the comprehensive impact of AI integration with other emerging technologies on enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction efforts. (5) Given the 2012–2022 time span of this study, future research can extend the research period to examine the long-term effects of AI on the synergistic effects of textile enterprises’ pollution and carbon emissions reduction.

CRediT authorship contribution statementLelai Shi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Methodology, Data curation. Qiuhang Chen: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Software, Data curation. Hong Lin: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

This work was sponsored in part by the Philosophy and Social Science Research Project of Hubei Provincial Department of Education (Grant No 22Q081) and the Special Fund Project of Wuhan Textile University (Grant No D0401).