This study investigates how generative artificial intelligence (GenAI) transforms collaborative innovation by serving not only as a productivity tool but also as a cognitive partner in workplace problem-solving. Drawing on Piaget’s theory of assimilation and accommodation, we propose that the impact of GenAI depends on how users cognitively engage with it, either by fitting it into existing schemas (assimilation) or using it to restructure mental models and workflows (accommodation). To address our hypotheses, we conducted a randomized 2 × 2 factorial field experiment involving 371 professionals in South Korea to compare individuals and teams with or without access to GenAI. Participants completed an open-ended innovation challenge, and their cognitive strategies, emotional responses, and solution outcomes were measured using surveys, behavioral data, and expert evaluations. The results show that GenAI significantly improves innovation quality and emotional engagement, especially when users adopt accommodative strategies. Furthermore, accommodation mediates the integration of cross-functional knowledge, suggesting that cognitive adaptation is a critical mechanism for unlocking GenAI’s collaborative potential. These findings provide new theoretical insights into human–AI teaming, highlighting the importance of organizational support for cognitive flexibility in AI adoption. We conclude that GenAI’s value is maximized not through passive use, but through reflective collaboration and schema-level transformation.

The modern workplace is undergoing a significant transformation driven by the rapid diffusion of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI). What began as a series of automation tools aimed at enhancing productivity has now evolved into a complex and nuanced relationship between humans and machines. Recent advances in large language models (LLMs), such as GPT-4, have positioned AI as more than a support mechanism, situating it as a potential cognitive collaborator that is capable of ideating, evaluating, and even engaging in team-based tasks traditionally reserved for human professionals (Dell’Acqua et al., 2025; Fahad et al., 2024). In this shifting terrain, the central question is no longer whether AI can improve individual efficiency, but if it can fundamentally reshape team interactions, knowledge sharing, and how innovation emerges in organizational contexts.

Teamwork has long been considered the cornerstone of innovation and knowledge-intensive work (Jansen et al., 2006; West & Hirst, 2005). Collaborative advantages are typically attributed to enhanced performance through joint problem-solving, improved knowledge integration across functional boundaries, and positive emotional engagement that sustains creativity (Costa & Monteiro, 2016). However, these assumptions were built on the premise that collaboration is a uniquely human process, a foundation that has been challenged by the introduction of GenAI. This shift raised important questions: Can machines substitute for or augment collaborative functions? Can they facilitate knowledge recombination across silos? Finally, can they trigger the same emotional responses that underpin effective teamwork?

While early research has confirmed that AI can enhance productivity and reduce routine burdens (Noy & Zhang, 2023), less is understood about how it can reshape the cognitive dynamics of collaboration. Dell’Acqua et al. (2025) provide vital evidence that GenAI-augmented individuals can perform at a level comparable to small human teams, showing that AI can elevate performance. Our study moves a step further by examining how this occurs. Specifically, we argue that the explanatory mechanism lies in how humans cognitively engage with AI through the dual processes of assimilation and accommodation.

To analyze this hypothesis, we draw on Piaget’s theory of cognitive adaptation, which suggests that assimilation involves integrating new tools into existing schemas without altering fundamental workflows (Piaget & Cook, 1952). Conversely, accommodation focuses on restructuring mental models, problem definitions, and role conceptions in response to novel input. This framework offers explanatory power that prevailing adoption models such as TAM or UTAUT cannot provide, as it addresses the depth of cognitive transformation rather than surface-level acceptance or usage.

Importantly, while accommodation is often portrayed as superior for fostering innovation, it may also carry risks. For instance, deep restructuring can lead to confusion, the erosion of valuable expertise, or misalignment with organizational routines. Thus, the optimal approach may not be wholesale accommodation but a dynamic balance, with assimilation providing stability and efficiency, and accommodation enabling creativity and exploration. Recognizing this tension enhances our theoretical contributions while cautioning against overly normative assumptions (Kim & Park, 2023).

To test our hypotheses, we conducted a randomized 2 × 2 factorial field experiment with 371 professionals working in technology, marketing, and R&D in South Korea. Participants completed an open-ended innovation challenge either individually or in teams, with or without GenAI support. We then measured solution quality, novelty, feasibility, cross-functional integration, and emotional engagement, while classifying cognitive strategies as assimilative or accommodative. This multi-method design, which combines surveys, behavioral traces, and interviews, provides a robust platform for exploring how GenAI influences both outcomes and the underlying cognitive processes.

Our findings make three main contributions. First, we confirm that GenAI enhances both individual and team innovation outcomes, extending the evidence of AI-enabled productivity. Second, we reveal that cognitive accommodation explains why GenAI improves knowledge integration and emotional engagement, thereby uncovering a mechanism missed in earlier studies. Third, we highlight important boundary conditions—cultural (collectivism, power distance), organizational (support for experimentation), and emotional (ethical anxiety)—that determine whether accommodation emerges and if it is beneficial.

To ensure the research design and contributions are transparent, we summarize our entire process in Table 1. This table outlines the sequential stages, from the theoretical framework through to the hypotheses, methodology, data collection, analysis, and results, and finally to implications and future research directions. Presenting the study in this structured form clarifies how the work extends prior research on the link between GenAI and collaboration and underscores its unique theoretical and practical contributions.

Research flow of the study.

GenAI is reshaping how organizations conceptualize and execute innovation. Unlike earlier AI systems that primarily focused on automating structured and repetitive tasks, GenAI tools powered by LLMs can engage in human-like reasoning, language production, and creative ideation (Brynjolfsson et al., 2025). These affordances allow it to function as a potential cognitive collaborator in innovation processes (Khan et al., 2025).

Research across diverse sectors has confirmed GenAI’s dual potential. For instance, in manufacturing and fintech industries, it has enhanced exploratory and exploitative innovation by enabling rapid iteration and reducing product development uncertainty (Almansour, 2023; Al-Khatib, 20244). Additionally, in small and medium enterprises, AI-driven marketing has improved customer engagement and responsiveness (Abrokwah-Larbi & Awuku-Larbi, 2024). Yet cautionary perspectives emphasize that over-reliance may result in the homogenization of ideas or superficial novelty (Doshi & Hauser, 2024). Thus, GenAI’s effectiveness is contingent on many factors, including organizational openness (Laursen & Salter, 2006), individual expertise (Xu et al., 2024), and alignment with strategic foresight (Mubarak et al., 2025).

GenAI and knowledge integrationKnowledge management (KM) is central to innovation in complex, cross-functional environments. Particularly, GenAI augments KM by facilitating contextualized knowledge access, enabling synthesis across domains, and promoting real-time learning (Taherdoost & Madanchian, 2023). Importantly, GenAI can accelerate knowledge recombination, a key driver of innovation performance (Costa & Monteiro, 2016). For example, Corvello et al. (2023) show how AI-enabled corporate–startup units act as knowledge brokers within ecosystems. Furthermore, Idrees et al. (2023) underscore that effective KM underpins new product development success, reinforcing the importance of AI-enabled recombination and contextual learning mechanisms.

At the same time, human interaction remains indispensable, as social trust and relational capital mediate usage effectiveness even in AI-enhanced KM systems (He et al., 2009). However, there are concerns that excessive automation may crowd out tacit, experiential learning (Balasubramanian et al., 2022). Thus, successful integration requires balancing automation with mechanisms that preserve cognitive diversity, human judgment, and interpersonal trust.

Assimilation and accommodation as cognitive processesPiaget’s assimilation–accommodation framework (Piaget & Cook, 1952) provides a powerful lens for explaining heterogeneous AI use. Assimilation refers to fitting new inputs into existing schemas, while accommodation involves restructuring mental models to integrate new experiences (Kang & Park, 2023). Applied to GenAI, assimilation occurs when employees utilize AI to accelerate tasks without altering their approach, whereas accommodation involves AI prompting a problem to be reframed or roles to be redefined (Raisch & Krakowski, 2021).

This distinction resonates with the tension between exploitative and exploratory innovation (Jansen et al., 2006). Studies of AI-enabled teamwork have confirmed that accommodative behaviors, such as openness, iterative feedback, and flexibility, correlate with superior innovation performance (Soomro et al., 2024). Beyond cognitive outcomes, emotional responses can significantly shape whether users assimilate or accommodate. Positive emotions, such as enthusiasm and curiosity, may expand the willingness to experiment with AI (Xu et al., 2024). Conversely, unfamiliarity or opacity can generate negative feelings like frustration and disengagement (Chen et al., 2012; Lee, 2008).

Crucially, accommodation presents not only a cognitive opportunity but also an emotional challenge. Restructuring established schemas can be anxiety-inducing, especially when employees perceive AI as destabilizing roles or threatening expertise. Furthermore, recent work highlights how ‘ethical anxiety’ about AI’s societal implications can moderate its effect on innovation (Zhu et al., 2025). Acknowledging this tension allows for a more balanced perspective: accommodation may enhance innovation while simultaneously requiring psychological safety and managerial support.

Cultural and organizational boundary conditionsNational culture is critical in shaping how employees engage with disruptive technologies such as GenAI. Research on cross-cultural management and innovation has long emphasized that values such as power distance, collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance can significantly influence openness to change, willingness to challenge established routines, and propensity to engage in exploratory behavior (Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 2004). These dimensions are particularly salient when considering the assimilation–accommodation framework, as they influence whether individuals will fit AI into existing schemas or if they require restructuring to embrace novelty.

In high power distance contexts, where hierarchical authority and deference to superiors are emphasized, employees may be less inclined to radically reframe problems or propose unconventional AI-enabled solutions. Prior research has indicated that this distance can reduce participatory decision-making and weaken the likelihood of expressing divergent perspectives, thereby favoring assimilative rather than accommodative use of new technologies (Kirkman et al., 2009).

Cultural collectivism presents an ambivalent influence. On the one hand, collectivism can emphasize collaboration, harmony, and group cohesion, which can support the shared exploration of GenAI and foster trust in its use (Triandis, 1995). On the other hand, it may encourage conformity, suppressing individual-level experimentation or radical reframing, thereby limiting the expression of accommodation (Earley, 1993). Teams in such settings may be more comfortable integrating AI for incremental efficiency gains rather than challenging established schemas.

High uncertainty avoidance, another prominent cultural trait, can often discourage risk-taking and schema disruption (Hofstede, 2001). Employees in such environments may prefer predictable, rule-based uses of AI that align with existing procedures, again reinforcing assimilation. Studies on technological adoption in uncertainty-averse cultures have confirmed that while structured training can increase usage, individuals remain cautious about redefining roles or experimenting with untested workflows (Steenkamp, 2001).

Taken together, these cultural dynamics suggest that cognitive accommodation is not a universally accessible strategy; instead, it is bounded by institutional and cultural norms. In cultures characterized by less power distance, more individualism, and greater tolerance for uncertainty, such as Scandinavian or Anglo-American contexts, employees may be more willing to restructure mental models and embrace accommodation. In contrast, assimilation is likely to dominate in more hierarchical and stability-oriented settings. This insight underscores the importance of future comparative studies across cultural contexts to evaluate the generalizability of findings on GenAI-enabled collaboration (Taras et al., 2010; Tung, 2008).

Beyond individual cognition and culture, broader organizational and environmental factors also influence whether accommodation occurs (wael Al-Khatib, 2023). Drawing on the Technology–Organization–Environment (TOE) framework, we argue that:

- •

Technological factors (e.g., interface transparency, AI explainability) shape whether users trust AI enough to restructure schemas.

- •

Organizational factors (e.g., leadership support, training design, incentives for experimentation) foster the psychological safety necessary for accommodation.

- •

Environmental factors (e.g., government digital policies, industry norms) provide the resources and legitimacy necessary for deeper adoption.

For instance, organizations with explicit support for experimentation and learning are more likely to witness accommodative use of AI, whereas environments with rigid compliance regimes may reinforce assimilative patterns. This expanded perspective broadens our theoretical contribution by linking micro-level cognition to meso‑ and macro-level contexts.

The reviewed literature shows that GenAI’s impact on innovation is far from deterministic. The outcomes depend on individuals’ cognitive and emotional engagement, how cultural norms condition the willingness to restructure schemas, and whether organizational and environmental supports enable or constrain experimentation.

Theoretical frameworkIntegrating GenAI into organizational contexts introduces novel complexities in how individuals and teams interact with knowledge, technology, and one another. To capture these dynamics, we adopt Piaget’s theory of assimilation and accommodation (Piaget & Cook, 1952), which we argue provides a richer account of cognitive responses to AI than traditional technology adoption models such as the TAM or the UTAUT. While such models focus on predicting use intentions and adoption frequency, they do not explain the depth of cognitive restructuring that occurs when employees engage with AI as a collaborative partner.

Assimilation refers to incorporating new tools into existing mental models and workflows, allowing individuals to enhance task execution without fundamentally altering their role or perspective. For example, an employee who primarily uses GenAI to draft text, polish existing content, or refine preestablished ideas is engaging in assimilative use. In contrast, accommodation represents a deeper level of cognitive adaptation. For instance, it occurs when individuals or teams reconceptualize problem definitions, adopt unfamiliar strategies, or reconfigure collaborative dynamics in response to GenAI’s affordances. Thus, accommodation positions AI as an epistemic partner in the innovation process.

This dual-process lens is especially relevant for explaining GenAI’s impact on innovation outcomes. Prior studies (e.g., Dell’Acqua et al., 2025) have shown that individuals using GenAI can produce ideas comparable to those of small teams. Our framework advances this insight by explaining how such outcomes occur, specifically through the mediating role of cognitive accommodation. By explicitly contrasting assimilation and accommodation, this study provides a theoretical foundation for understanding why some users leverage GenAI merely as a productivity accelerator, while others achieve more transformative results.

Importantly, although accommodation often generates superior innovation outcomes, it is not without risks. Deep restructuring of schemas may create strategic confusion, erode valuable experiential expertise, or cause employees to feel overwhelmed due to continuous change. These downsides highlight that the optimal approach may not be to rely exclusively on accommodation, but instead to prioritize a dynamic balance between the two as assimilation offers efficiency and stability, while accommodation enables creativity and boundary-spanning integration. Thus, we position accommodation not as a universally superior strategy but as a conditional pathway whose value depends on context.

To capture this contextual dimension, we extend the assimilation–accommodation framework to incorporate organizational and cultural moderators. At the cultural level, factors like power distance, collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance can shape employees’ willingness to challenge schemas and restructure cognitive models. In high power-distance and collectivist contexts, they may default to assimilation, while in more individualistic, low uncertainty-avoidance cultures, accommodation may be more prevalent (Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 2004). At the organizational level, enablers such as leadership support, training that fosters psychological safety, and encouragement of experimentation increase the likelihood that accommodation will emerge and succeed. These insights align with the TOE framework, which emphasizes that technology adoption outcomes are shaped by the technology itself but also by organizational capabilities and support.

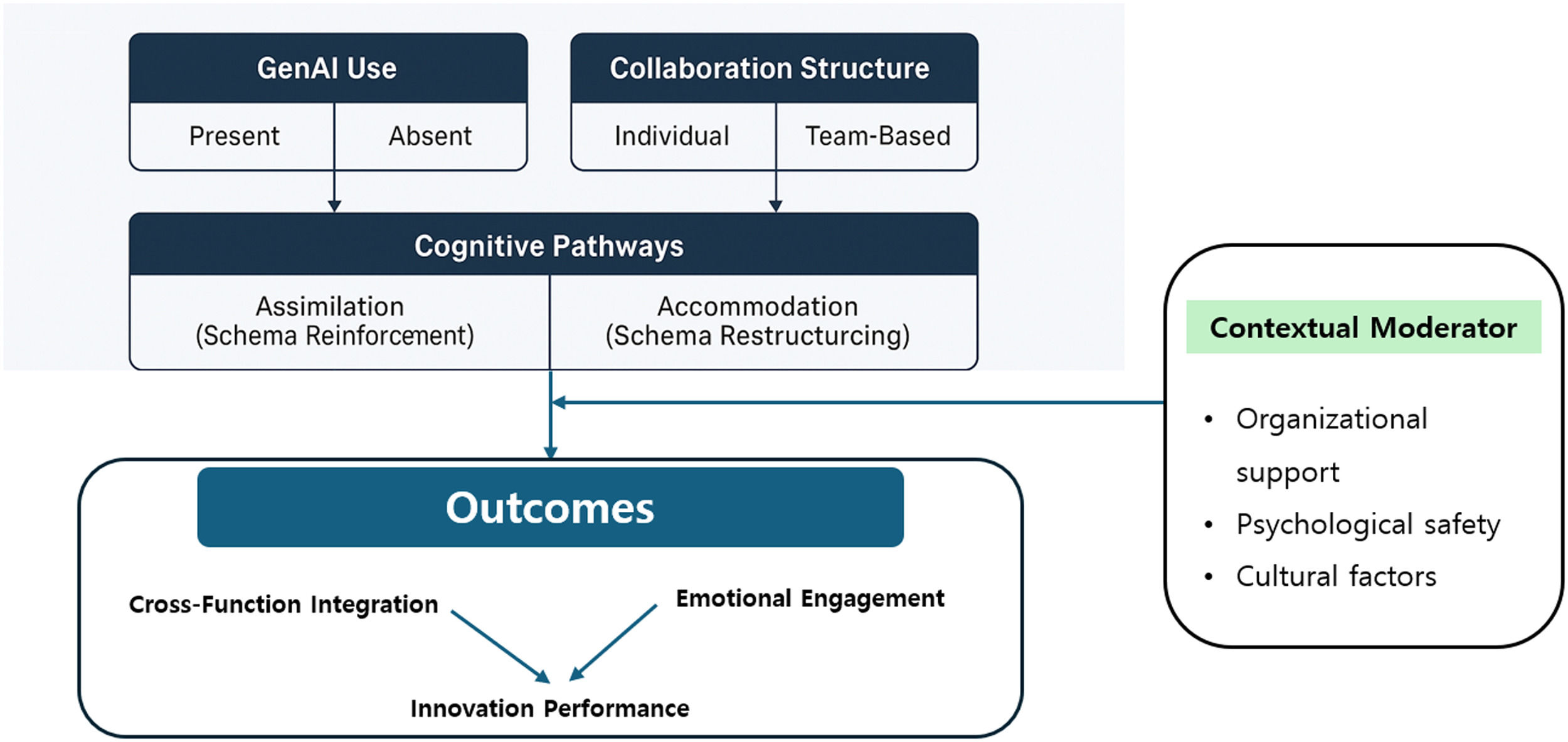

In sum, our theoretical framework proposes that GenAI functions as a cognitive collaborator rather than merely a productivity tool. Its impact is shaped by whether users adopt an assimilative or accommodative strategy, which mediates outcomes across three domains: (1) innovation performance (quality, novelty, feasibility), (2) knowledge integration (cross-functional balance), and (3) emotional engagement (positive or negative). We further argue that contextual moderators, like cultural values, organizational support, and environmental policies, condition the emergence and effectiveness of accommodation. These theoretical insights directly inform our hypotheses, which formalize the expected relationships among GenAI use, collaboration structure, cognitive pathways, and innovation outcomes.

As shown in Fig. 1, the research framework depicts how Generative AI use (present vs. absent) and collaboration structure (individual vs. team-based) influence innovation outcomes through two cognitive pathways: assimilation (schema reinforcement) and accommodation (schema restructuring). Notably, emotional engagement mediates the relationship between cognitive strategy and performance, while contextual moderators (organizational support, psychological safety, cultural factors) shape the direction and strength of these effects. Fig. 1 also mirrors the 2 × 2 factorial experiment design, providing a visual summary of the theoretical logic underlying Hypotheses 1 through 3.

Hypotheses developmentBuilding on the theoretical framework, we develop hypotheses linking GenAI use, collaboration structures, and cognitive engagement strategies to innovation outcomes. Our approach moves beyond existing studies focusing on whether GenAI improves performance (e.g., Dell’Acqua et al., 2025) by specifying how these improvements occur via assimilation and accommodation. We argue that GenAI’s impact is contingent on cognitive pathways, emotional responses, and contextual moderators, resulting in different patterns of performance, knowledge integration, and engagement.

GenAI and innovation performanceGenAI provides individuals and teams with unprecedented access to knowledge, diverse perspectives, and creative suggestions. Prior studies have demonstrated that individuals using GenAI can produce outputs comparable in quality to human teams (Dell’Acqua et al., 2025; Khan et al., 2025). These effects stem from efficiency gains as well as AI’s ability to expand cognitive search spaces and reduce ideation constraints (Fahad et al., 2024).

However, these outcomes critically depend on the cognitive strategy adopted. Assimilative use (i.e., integrating AI into established schemas) can support incremental improvements and ensure efficiency and feasibility, but it may limit novelty. Conversely, accommodative use involves reframing problems and adopting new perspectives, thereby fostering originality and holistic solutions. Yet accommodation also carries risks like cognitive overload, strategic confusion, or erosion of expertise. Thus, it is best understood as a high-risk/high-reward strategy, whereas assimilation ensures stability but may constrain breakthrough outcomes. We therefore expect GenAI to improve performance overall, with accommodation yielding the strongest benefits.

H1–1. Individuals using GenAI will demonstrate significantly stronger innovation performance.

H1–2. Teams using GenAI will demonstrate the highest level of innovation performance across all conditions.

H1–3. Users implementing accommodative strategies will outperform those using assimilative strategies, regardless of the collaboration structure.

GenAI and cross-functional knowledge integrationInnovation increasingly depends on integrating knowledge across technical, commercial, and strategic domains. GenAI has the potential to reduce functional silos by offering diverse prompts spanning multiple perspectives (Corvello et al., 2023; Soomro et al., 2024). However, the extent to which these suggestions are incorporated depends on users’ cognitive stance.

Assimilative users are likelier to interpret AI suggestions through the lens of their existing expertise, reinforcing disciplinary boundaries. In contrast, accommodative users are more willing to adopt and combine divergent perspectives, producing more balanced, cross-functional solutions. This logic extends the prior research on open innovation, showing that external knowledge only enhances performance when it is integrated into restructured internal schemas (Laursen & Salter, 2006). Therefore, while we expect GenAI to facilitate overall cross-functional integration, accommodation will serve as the primary driver of this effect.

H2–1. Individuals and teams using GenAI will exhibit more balanced integration of commercial and technical perspectives in their outputs.

H2–2. Users demonstrating accommodative engagement will produce more cross-functional outputs than assimilative users.

H2–3. In team-based GenAI conditions, accommodation will lead to better cross-functional knowledge integration than in individual-based conditions.

GenAI and emotional engagementEmotional dynamics are vital in sustaining collaboration and innovation. Positive emotions like enthusiasm and curiosity can broaden cognitive scope and increase persistence (Li et al., 2023), while negative emotions, such as frustration or anxiety, can narrow attention and reduce risk-taking (Chen et al., 2012). Emerging studies have suggested that GenAI can act as an emotional buffer by reducing stress, boosting self-efficacy, and sustaining momentum in collaborative tasks (Xu et al., 2024).

Cognitive strategies shape these emotional outcomes. For instance, assimilation tends to produce neutral or somewhat positive effects by reducing workload, while accommodation can generate stronger emotional responses, both positive and negative. On the one hand, accommodation may spark excitement and motivation by enabling new ways of thinking. On the other hand, it may also induce discomfort or ‘ethical anxiety’ as individuals confront the uncertainty and disruption associated with schema change (Zhu et al., 2025). Organizations that ensure psychological safety via training are critical in shaping whether accommodation becomes energizing or overwhelming. Therefore, we propose that accommodation enhances emotional engagement overall, though its effects are moderated by context.

H3–1. Individuals and teams using GenAI will report greater increases in positive emotions (e.g., excitement, engagement).

H3–2. Users engaging in accommodative interactions with GenAI will report greater positive emotional change than assimilative users.

H3–3. Emotional engagement will mediate the relationship between cognitive strategy and innovation performance, particularly in AI-enabled conditions.

Together, these hypotheses extend the existing research by showing that GenAI’s effectiveness is not uniform but mediated by cognitive strategies, moderated by cultural and organizational conditions, and manifested across performance, knowledge levels, and emotions. This approach advances the field by explaining how GenAI improves collaboration, thereby uncovering the cognitive and affective mechanisms that earlier studies had not identified.

MethodologyProceduresTo strengthen methodological clarity, we add an explicit rationale for employing a 2 × 2 factorial design. This design structure was selected as it enables the simultaneous examination of two central factors: GenAI availability (present vs. absent) and collaboration structure (individual vs. team-based), as well as their interactive effects on innovation outcomes. This format allows us to isolate the main effects while testing for interaction effects, thereby capturing whether GenAI’s influence differs across individual and collective contexts. This approach ensures internal validity via controlled manipulation and ecological validity by reflecting realistic work settings where AI tools are integrated into solo and team workflows.

The study recruited 371 mid-career professionals from various industries, including information technology, manufacturing, consumer goods, healthcare, finance, and digital services. This diverse participant pool reflects the organizational contexts where digital tools and cross-functional collaboration are most prevalent. Functional representation was balanced across research and development (32 %), marketing (28 %), planning and strategy (25 %), and other roles like operations and consulting (15 %). The sample included male and female professionals, with a median of 12 years of work experience, capturing perspectives across career stages. Importantly, conditions were assigned using a stratified randomization procedure accounting for prior AI exposure, job function, and digital fluency. This ensured a balanced representation across the four cells and minimized systematic bias in predisposition toward AI. In doing so, the experimental design preserved internal validity while simulating realistic workplace conditions, thereby enhancing ecological validity.

Participants engaged in a complex, open-ended innovation challenge intended to mirror the ambiguity and multidimensionality of real-world organizational problems. Example challenges included developing a novel digital product, reimagining customer service processes, or integrating sustainability principles into an existing offering. These tasks were chosen as they inherently allow for incremental (exploitative) improvements and radical (exploratory) innovation. This design ensured participants could engage in assimilative strategies (e.g., fitting GenAI into existing schemas) or accommodative strategies (e.g., restructuring mental models and reframing the problem in consideration of AI input).

The experiment was conducted in a controlled virtual environment and unfolded in several phases. Participants first completed a pre-task survey capturing demographic variables, baseline emotional state, digital literacy, and prior AI experience. Those assigned to the AI condition then undertook a 45-minute training module on prompt engineering and hands-on interaction with GPT-4. Subsequently, all participants entered a 90-minute problem-solving phase, either working alone or in dyads. Following task completion, they responded to a post-task survey measuring cognitive engagement, emotional responses, and perceptions of collaboration quality. Finally, a subset of participants volunteered for debrief interviews, providing qualitative insights into their reasoning processes and experiences with GenAI.

MeasuresThe study’s theoretical distinction centered on whether participants exhibited assimilation or accommodation when engaging with GenAI. Assimilation was defined as using AI to accelerate existing processes without changing fundamental problem framings, while accommodation entailed reframing problems, adapting strategies, or redefining roles based on AI-generated input. To capture these strategies, we employed a dual-method classification system combining survey data and qualitative evidence. Post-task survey items measured self-reported cognitive responses (e.g., “GenAI helped me rethink the task” vs. “I applied GenAI without changing my usual process”). In parallel, behavioral and qualitative data, including AI prompt histories, submitted solutions, and interview transcripts, were thematically analyzed for evidence of reframing and adaptive reasoning.

Participants were coded as accommodative if they scored above threshold levels on survey items reflecting schema change and displayed qualitative evidence of conceptual restructuring. Those who primarily used AI to accelerate routine outputs without altering their approach were classified as assimilative. Importantly, we acknowledge that assimilation and accommodation represent points on a continuum of cognitive adaptation, rather than a strict binary. To address this, we conducted supplementary robustness analyses treating accommodation as a continuous variable. These analyses confirmed that the primary effects reported in this study remain consistent, strengthening our confidence in the findings.

Innovation outcomes were assessed by independent expert raters who evaluated each solution based on quality, novelty, and feasibility using a 10-point Likert scale adapted from Dell’Acqua et al. (2025). Raters were blind to participant conditions and identity, and inter-rater reliability was acceptable (ICC2 = 0.51). Cross-functional knowledge integration was also evaluated by experts, who judged the extent to which technical and commercial perspectives were jointly represented. A balance index ranging from 1 (functionally skewed) to 7 (fully integrated) was applied, with 4 indicating a balanced integration of perspectives.

Emotional engagement was measured by comparing participants’ pre- and post-task self-reports of affective states. Positive emotions like excitement and motivation, as well as negative emotions such as frustration and anxiety, were assessed on a 7-point Likert scale. Change scores were computed to capture how the interaction between the innovation task and GenAI shaped affective dynamics. These emotional shifts were analyzed as both outcomes and moderators of cognitive strategies. Consistent with theory, we anticipated that accommodation would produce more emotionally activating experiences than assimilation.

To enhance transparency and replicability, we have moved the detailed measurement instruments to Appendix A, which provides the full list of survey items used for assimilation, accommodation, emotional engagement, digital literacy, and control variables. This ensures future scholars can replicate or extend our approach.

Data analysis strategyThe data were analyzed using a multi-level approach integrating cognitive classification, affective change, and performance outcomes. Initial balance checks confirmed equivalence across experimental groups in terms of demographics, AI familiarity, and digital literacy, thereby validating the randomization procedure. The main effects of GenAI use and collaboration structure were tested using OLS regression and two-way ANOVA, with innovation performance and knowledge integration as dependent variables. Control variables like gender, role, and prior AI experience were included where relevant.

To examine the mediating role of cognitive strategy, we conducted causal mediation analyses using the PROCESS macro (Model 4), with bootstrapped confidence intervals (5000 resamples) for each innovation outcome. Moderated mediation models (PROCESS Model 7) were then employed to test whether emotional engagement moderated the relationship between cognitive strategy and performance. We expected accommodation to yield higher-quality solutions through increased positive affect, particularly in team-based conditions.

Finally, qualitative data (prompt sequences, team transcripts, and interview reflections) were thematically coded using a structured scheme for reframing, reinterpretation, and role adaptation. Independent coders achieved 89 % inter-rater reliability, with discrepancies resolved through consensus. This triangulated approach validates the survey-based classification of assimilation and accommodation with behavioral and qualitative evidence, thereby increasing the rigor of our findings.

Descriptive results of experimental groupsTo provide an overview of the experimental outcomes, Table 2 summarizes the descriptive statistics across the four conditions. The results show clear differences between groups: participants using GenAI (whether individually or in teams) produced solutions that were higher in quality, novelty, and feasibility than those in non-AI conditions. Moreover, GenAI conditions exhibited stronger cross-functional knowledge integration and positive emotional changes, accompanied by somewhat greater reductions in negative emotions. These descriptive patterns support our theoretical expectation that GenAI enhances innovation performance and engagement, with team-based GenAI producing the strongest overall outcomes.

Descriptive statistics by experimental condition.

Table 2 summarizes the descriptive results across the four experimental conditions. Notably, participants using GenAI consistently outperformed those in non-AI conditions in terms of solution quality, novelty, feasibility, and cross-functional knowledge integration. The most significant differences were observed in novelty and integration, suggesting that GenAI’s contributions extend beyond efficiency to stimulate more original and cross-disciplinary outcomes. Emotional engagement also systematically differed, as individuals and teams using GenAI reported substantial increases in positive emotions. However, they also experienced somewhat greater frustration and anxiety compared to the baseline, reflecting the emotionally complex nature of accommodation. As shown in Table 2, team-based GenAI users exhibited the strongest outcomes overall, combining the highest quality solution (M = 7.5, SD = 0.6) and integration (M = 6.1, SD = 0.5) with the largest positive emotional shift (+1.2).

Effects of GenAI and collaboration structureTwo-way ANOVA and regression analyses confirmed that GenAI significantly improved performance outcomes (see Table 3). Individuals using GenAI outperformed those without it (β = 0.41, p < .01), and teams using GenAI achieved the strongest results overall (β = 0.58, p < .001). Teams without GenAI did not significantly outperform individuals without it (β = 0.11, n.s.), suggesting that collaboration alone does not drive performance gains. These findings support H1–1 and H1–2, establishing that GenAI enhances individual performance and amplifies team-based outcomes when combined with collaboration.

Regression and ANOVA results (main effects of GenAI and collaboration).

Causal mediation analysis revealed that accommodation mediated the relationship between GenAI use and innovation outcomes (see Table 4). Specifically, accommodation explained 37 % of GenAI’s indirect effect on novelty and 29 % of its effect on integration. In contrast, assimilation did not significantly mediate novelty but was linked to feasibility. These findings support H1–3 and H2–2, highlighting accommodation as the mechanism through which GenAI fosters creativity and integration.

Mediation analysis (accommodation as a mediator).

*Note: **p < .01; p < .05. Indirect effects estimated via bootstrapping with 5000 resamples.

Moderated mediation analysis showed that positive emotional engagement amplified the effects of accommodation (see Table 5). Participants reporting higher levels of positive emotions (e.g., excitement, motivation) after using GenAI were likelier to translate accommodation into creative, high-quality outcomes. Conversely, negative emotions sometimes dampened this relationship, highlighting the ambivalent emotional impact of cognitive restructuring. These findings support H3–1 and H3–2.

Contrary to our expectations, H2–3 was not supported, as team accommodation did not produce significantly higher levels of cross-functional knowledge integration than individual accommodation. While teams with GenAI displayed higher integration scores, the difference between team- and individual-based accommodation did not achieve statistical significance.

This finding is noteworthy as it challenges the prevailing assumption that teams naturally generate more integrative outcomes when supported by AI. Our results suggest that the social dynamics of team decision-making may dampen the transformative potential of accommodation. Interviews and qualitative reflections revealed that team members often preferred safe and consensus-driven choices over the more disruptive ideas proposed by GenAI. For instance, one participant in a strategy function observed:

“We wanted to explore AI’s radical idea, but within the team, we quickly voted for the safer option to avoid conflict.”

This reflection illustrates how consensus pressure and conformity norms can act as countervailing forces in group contexts. Even when GenAI expanded the cognitive search by offering novel ideas, the social realities of teamwork can curtail schema restructuring, steering groups back toward incremental assimilation rather than full accommodation. This suggests that team-level accommodation is not simply a function of exposure to AI-generated novelty but is highly contingent on psychological safety, group norms, and leadership facilitation.

Thus, the absence of support for H2–3 adds valuable nuance to our framework, highlighting that the benefits of accommodation are not universally scalable from individuals to teams. Instead, organizational interventions may be required to mitigate consensus-seeking tendencies and encourage teams to engage with the more challenging and potentially disruptive suggestions that GenAI introduces.

Illustrative cases of assimilation vs. accommodationWhile statistical results helped establish that accommodation is a key mediator of GenAI’s effects, qualitative data illustrate how these cognitive strategies manifested in practice. Examining both participant reflections and AI prompt histories enables us to distinguish clearly between assimilation and accommodation.

Assimilation Example:

A marketing professional described their experience as follows:

“I used GenAI to polish my loyalty app idea. It helped with phrasing and structure, but my concept stayed the same.”

The participant’s prompt history reinforced this account, consisting of instructions such as “Refine my draft” and “Make this proposal more concise,” demonstrating that GenAI was primarily used to optimize an existing schema and improve efficiency and presentation without altering the underlying concept. This is a classic case of assimilation, where new tools are integrated into established mental frameworks.

Accommodation Example:

An R&D participant reported the following interaction with GenAI:

“GenAI made me completely rethink the customer’s role. Instead of just a loyalty program, I envisioned a co-creation platform where customers design features with us.”

Their prompt history included exploratory questions such as “What if customers contributed their own designs?” and “How would this change our business model?” These prompts show an iterative process of schema restructuring, where the participant allowed GenAI to reconceptualize both the problem and the solution. This is a clear illustration of accommodation, in which cognitive schemas are redefined to integrate disruptive insights, which fundamentally differs from the assimilation example.

Together, these cases highlight the mechanism underlying our findings: assimilation streamlines existing approaches and ensures feasibility, while accommodation fosters deeper transformation by reconfiguring how problems are framed and solutions are conceived.

As shown in Table 5, our analyses provide robust evidence that GenAI acts as a cognitive collaborator rather than just a productivity tool. Several overarching findings emerge:

- •

GenAI enhances innovation outcomes. Across conditions, GenAI users delivered solutions that were higher quality and more novel, feasible, and cross-functionally integrated than those of non-AI users. Team GenAI use produced the strongest descriptive outcomes, underscoring its potential for collective creativity.

- •

Accommodation mediates GenAI’s effects. Statistical analyses confirmed that accommodation is the primary mechanism through which GenAI drives novelty and integration. Assimilation played a supportive role, contributing to feasibility and efficiency, but did not account for breakthrough innovations.

- •

Emotional engagement moderates accommodation. Positive emotions amplified the benefits of accommodation, while negative ones sometimes constrained them. This finding highlights the ambivalent emotional dynamics of accommodation, which can be simultaneously energizing and anxiety-inducing.

- •

Team accommodation did not surpass individual accommodation. The lack of support for H2–3, combined with qualitative insights, suggests that team dynamics, particularly consensus pressures, can suppress the radical potential of accommodation, identifying important boundary conditions in how GenAI supports collaborative innovation.

- •

Qualitative evidence vividly illustrates cognitive processes. Participant quotes and prompt-sequence analyses bring to life the distinction between assimilation and accommodation. This anecdotal evidence shows how some users leveraged GenAI for efficiency and refinement, while others restructured their cognitive schemas to generate transformative ideas.

Moderated mediation (emotional engagement as a moderator).

Overall, these results provide a nuanced account of how GenAI supports innovation. The evidence confirms that GenAI’s impact is not uniform but depends on users’ cognitive strategies, the emotional experiences triggered by schema change, and team social dynamics. By combining statistical evidence with qualitative illustrations, this study advances the understanding of GenAI as a partner in innovation, revealing both its potential and its limitations. Table 6 presents the hypothesis test results and the associated key evidence.

Summary of hypothesis test results.

This study aimed to uncover the cognitive mechanisms through which GenAI influences collaborative innovation. Building on Piaget’s concepts of assimilation and accommodation, we show how individuals and teams engaging with AI fundamentally shape the novelty, feasibility, integration, and emotional experience of their outputs. Across a randomized 2 × 2 field experiment involving 371 professionals, our findings demonstrate that GenAI consistently enhances innovation outcomes, but its transformative potential is primarily realized through cognitive accommodation.

A central contribution of this study is the finding that assimilation and accommodation are not mutually exclusive but represent complementary pathways. While accommodation emerged as the primary mechanism driving novelty and cross-functional integration, it also carries risks of confusion, disruption, and emotional strain. In contrast, assimilation stabilized workflows, preserved established expertise, and ensured feasibility. Therefore, our results suggest that the optimal approach may not be a wholesale embrace of accommodation, but rather a dynamic balance between assimilation for efficiency and accommodation for transformation. This nuanced view moves beyond the assumption that accommodation is always superior, highlighting the importance of strategic calibration.

However, our findings must be interpreted in a South Korean cultural context, which is characterized by relatively high power distance, collectivism, and uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede, 2001; House et al., 2004). These cultural traits may shape how employees respond to GenAI and the likelihood of engaging in accommodation. For instance, a high power distance can discourage schema-challenging behaviors, while collectivist values may foster collaboration but also conformity pressures. Similarly, high uncertainty avoidance may limit the willingness to adopt disruptive reframing, as suggested by AI. This implies that accommodation may be more readily embraced in cultures with less hierarchy and greater tolerance for uncertainty, such as Scandinavian or Anglo-American contexts. Thus, future comparative research is needed to assess how cultural norms condition the assimilation–accommodation balance in AI-supported work.

Our second contribution lies in showing that accommodation is both cognitively demanding and emotionally complex. While accommodation often generated enthusiasm and engagement, it also provoked frustration and anxiety among some participants. These findings resonate with recent research on ‘ethical anxiety’ surrounding AI adoption (Zhu et al., 2025), which shows that employees may feel both energized and unsettled when adapting to AI-driven change. For managers, this underscores the importance of ensuring a psychologically safe and supportive context that allows employees to navigate the discomfort of schema restructuring while still capitalizing on its creative benefits.

The effectiveness of accommodation is not determined solely by individual cognition, as it is also shaped by organizational and environmental contexts. Drawing on the TOE framework, we argue that three sets of conditions are critical in supporting effective GenAI use:

- •

Technological conditions like the transparency and usability of GenAI systems, influencing trust and the willingness to experiment;

- •

Organizational conditions like leadership encouragement, training design, and experimentation incentives, which create the psychological safety required for accommodation;

- •

Environmental conditions like government policies promoting digital transformation and industry norms, which legitimize experimentation and provide necessary resources.

By embedding our cognitive framework within this broader multi-level perspective, we extend its theoretical scope and highlight avenues for future research on institutional enablers of AI-supported innovation.

Our findings also carry practical implications for designing organizational interventions. Many current corporate training programs mainly focus on prompt engineering, which primarily supports assimilation. To foster accommodation, organizations must move toward active learning pedagogies that encourage playful experimentation and reflective practice. For example, interactive workshops or simulation platforms can help employees develop the metacognitive skills necessary for restructuring schemas. As recent work on using short-form video platforms for active learning suggests (Liang et al., 2025), training that emphasizes exploration and reflection can make AI adoption both engaging and transformative.

However, organizations must also anticipate and manage the emotional ambivalence of accommodation. This involves normalizing discomfort, providing platforms for employees to share experiences, and equipping managers to support staff through the uncertainties of cognitive restructuring. Ethical considerations are also crucial. While GenAI can democratize access to knowledge, it also raises concerns about bias, transparency, and deskilling. Therefore, training and policy must balance empowerment with safeguards to ensure responsible adoption.

Finally, this study contributes to existing theory by explaining how GenAI enhances innovation. Prior research, such as Dell’Acqua et al. (2025), has demonstrated that individuals using GenAI can perform at levels comparable to those of small teams. Our study goes further by showing the mechanism underlying this effect, as accommodation mediates the relationship between GenAI use and innovation outcomes. That is, GenAI does not simply increase individuals’ productivity; instead, it functions as a cognitive collaborator enabling schema restructuring. This clarification positions our work as a theoretical advancement, moving the field beyond documenting performance gains to explaining their cognitive and emotional foundations.

In sum, this study offers a nuanced account of GenAI’s role in collaborative innovation. Particularly, it enhances performance not uniformly but selectively, depending on whether users assimilate it into existing schemas or accommodate it by restructuring their thinking. These pathways are shaped by cultural norms, organizational enablers, and emotional dynamics. Our findings contribute both theoretically and practically by integrating quantitative results with qualitative illustrations. For scholars, we provide a framework linking cognitive adaptation to innovation outcomes in AI-supported work. For practitioners, we offer guidance on balancing assimilation and accommodation, designing training that fosters schema restructuring, and supporting employees in the emotional complexities of AI adoption.

ConclusionThis study examined how GenAI reshapes collaborative innovation by functioning not only as a productivity tool but also as a cognitive partner. Building on Piaget’s framework of assimilation and accommodation, we conducted a randomized 2 × 2 field experiment with 371 professionals. Our findings demonstrate that GenAI enhances innovation outcomes across quality, novelty, feasibility, and cross-functional integration. Importantly, we show that cognitive accommodation is the key mechanism explaining these effects, and that its influence is amplified (or sometimes constrained) by emotional engagement, cultural norms, and team dynamics.

Theoretical contributionsOur findings contribute to the emerging literature on AI in organizations in several ways. First, we move beyond prior work that demonstrated that GenAI improves performance (e.g., Dell’Acqua et al., 2025) by explaining how this occurs—through accommodation-driven schema restructuring. Second, we show that assimilation and accommodation are not opposing strategies but rather complementary pathways. Assimilation supports efficiency and feasibility, while accommodation fosters transformation and novelty. Third, by integrating cultural boundary conditions, organizational enablers, and emotional ambivalence, we provide a multi-level framework that situates cognitive adaptation within broader institutional and affective contexts. Together, these insights advance existing theory on human–AI collaboration by linking cognitive mechanisms to innovation outcomes in a more nuanced manner.

Practical and managerial implicationsFor managers, our results underscore that effectively leveraging GenAI requires more than just deploying the technology. Organizations must actively cultivate accommodative mindsets through training, ensuring psychological safety, and implementing leadership practices that encourage experimentation. Training programs should go beyond prompt engineering, incorporating active learning pedagogies that foster reflection, playful exploration, and metacognitive awareness.

However, managers must also recognize the emotional ambivalence of accommodation. Employees may feel energized by new insights while also experiencing anxiety or frustration. Thus, supporting staff through these challenges, such as by normalizing discomfort, coaching, and fostering open dialogue, is critical to sustaining engagement. Finally, ethical considerations must not be overlooked. GenAI adoption raises issues of bias, transparency, and potential deskilling. Therefore, organizations should embed responsible AI practices into training and governance systems, ensuring that employees both benefit from and trust AI-enhanced collaboration.

Limitations and future researchDespite its contributions, this study has several limitations that provide opportunities for future research. First, our design was cross-sectional, capturing a snapshot of cognitive responses to GenAI during a single innovation task. However, assimilation and accommodation are likely temporal processes. For instance, users may initially engage in assimilation to develop familiarity and confidence before gradually adopting accommodation as they become more comfortable with AI. Thus, future research should employ longitudinal designs to trace this evolution and identify the triggers, such as training interventions, organizational support, or repeated exposure, that shift users from assimilation to accommodation.

Second, while our sample of South Korean professionals provided strong ecological validity, cultural boundary conditions may limit the generalizability of the findings. Therefore, comparative studies across low power-distance, individualistic, and uncertainty-tolerant contexts are needed to evaluate whether accommodation is equally prevalent and effective in different cultural environments.

Third, although we integrated qualitative insights, further ethnographic or in-depth case studies could reveal how team norms, leadership styles, or organizational climates shape the adoption of accommodative strategies. Future work should also explore how power dynamics within teams influence whether AI-generated disruptive ideas are embraced or suppressed.

Finally, future studies should pay closer attention to the ethical implications of AI-enabled work. For instance, how do concerns about surveillance, data privacy, or algorithmic bias affect employees’ willingness to engage in accommodation? Longitudinal and cross-cultural investigations of these ethical anxieties could illuminate how to design AI systems that are effective, trustworthy, and inclusive.

Data availabilityThe data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

CRediT authorship contribution statementMin Jae Park: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization.

We have no conflict of interests to declare in this research.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Korea and the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF-2024S1A5A8020272).

Survey instruments and measurement details.

AI as a Cognitive Collaborator: Assimilation and Accommodation in Human–Machine Teaming for Innovation