Empirical evidence demonstrates that motivated employees mean better organizational performance. The objective of this conceptual paper is to articulate the progress that has been made in understanding employee motivation and organizational performance, and to suggest how the theory concerning employee motivation and organizational performance may be advanced. We acknowledge the existing limitations of theory development and suggest an alternative research approach. Current motivation theory development is based on conventional quantitative analysis (e.g., multiple regression analysis, structural equation modeling). Since researchers are interested in context and understanding of this social phenomena holistically, they think in terms of combinations and configurations of a set of pertinent variables. We suggest that researchers take a set-theoretic approach to complement existing conventional quantitative analysis. To advance current thinking, we propose a set-theoretic approach to leverage employee motivation for organizational performance.

La evidencia empírica demuestra que los empleados motivados obtienen un mejor desempeño organizativo. El objetivo de este trabajo conceptual es expresar el progreso que se ha realizado en comprender la motivación de los empleados y el desempeño organizativo y sugerir modos de avanzar en la teoría relacionada con la motivación de los empleados y su desempeño organizativo. Reconocemos las limitaciones existentes en el desarrollo de la teoría y sugerimos una aproximación de investigación alternativa. El actual desarrollo de la teoría de la motivación se basa en un análisis cuántico convencional (p.ej. análisis de regresión multiple, modelos de ecuaciones estructurales). Dado que los investigadores están interesados en el contexto y el entendimiento de este fenómeno social holístico, se analizan en términos de combinaciones y configuraciones de un conjunto de variables pertinentes. Sugerimos que los investigadores tomen una aproximación teórica conjunta para complementar los análisis cuantitativos convencionales. Para avanzar en el pensamiento actual, proponemos una aproximación teórica conjunta para impulsar la motivación de los empleados y lograr un mayor desempeño organizativo.

Organizations, regardless of industry and size, strive to create a strong and positive relationship with their employees. However, employees have various competing needs that are driven by different motivators. For example, some employees are motivated by rewards while others focus on achievement or security. Therefore, it is essential for an organization and its managers to understand what really motivates its employees if they intend to maximize organizational performance.

Traditional motivation theories focus on specific elements that motivate employees in pursuit of organizational performance. For example, motives and needs theory (Maslow, 1943) states that employees have five level of needs (physiological, safety, social, ego, and self-actualizing), while equity and justice theory states that employees strive for equity between themselves and other employees (Adams, 1963, 1965). However, current research on employee motivation is more cross-disciplinary and includes fields such as neuroscience, biology and psychology. It seems that current research is aiming to bring together and revolutionize traditional motivation theories into a more comprehensive theory that encompasses the traditional perspectives of management, human resources, organization behavior with new perspectives in neuroscience, biology and psychology. For example, Lawrence and Nohria (2002) use cross-disciplinary perspectives to explain how human nature is the foundation of employee motivation. They argue that it is human nature for employees to possess four drives – the drive to acquire, bond, comprehend and defend – and these drives are the foundation for employee motivation. Their research also specifies organizational levers that fulfill these drives. Reward systems fulfill the drive to acquire, culture fulfills the drive to bond, job design fulfills the drive to comprehend, and performance-management and resource allocation processes fulfill the drive to defend (Lawrence & Nohria, 2002; Nohria, Groysberg, & Lee, 2008). When these organizational levers are used to fulfill employee drives and motivation, organizational performance is maximized.

The objective of this conceptual paper is two-fold: (1) to articulate the progress made on understanding employee motivation and organizational performance, and (2) to suggest how the theory concerning employee motivation and organizational performance may be advanced by acknowledging the existing limitations of theory development and adopting an alternative research approach for examining this relationship.

Current motivation theory development is based on the template of conventional quantitative analysis (e.g., multiple regression analysis, structural equation modeling), which is clearly the dominant way of conducting social research today (Fiss, 2011; Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2013). Although conventional quantitative analysis is considered by most in the discipline to be rigorous and the most scientific of the analytical methods available to social researchers (Ragin, 1987, 2000), we argue that these methods are centered on correlations and other measures of association which are symmetric by design and not the only means of understanding employee motivation and organizational performance. Symmetric analysis assumes that the effects of independent variables are both linear and additive. To estimate the net effect of a given independent variable, researchers offset the impact of other causal conditions by subtracting from the estimate of the effect of each causal variable any explained variation in the dependent variable it shares with other causal variables, see Ragin (2008) for more in depth discussion. The problem with theory development using conventional quantitative analysis is that the assessment of net effects is dependent on model specification, and this requires strong theory and deep substantive knowledge, which is the very objective of research in the first place.

Since quantitative researchers are interested in context and understanding social phenomena holistically, the tendency is to think in terms of combinations and configurations of a set of pertinent variables, often termed “casual recipes”, where causally relevant conditions combine to explain how a given outcome is achieved. A set-theoretic approach allows for configurational thinking and complex causality, which complements conventional quantitative analysis. The set-theoretic approach reveals how different conditions combine and whether there is only one combination or several different combinations of conditions (causal recipes) capable of generating the same outcome (Ragin, 2008).

In the next three sections, we articulate the progress made on understanding employee motivation and organizational performance by reviewing existing employee motivation theories, and the current state of play on work motivation and organizational performance. In the final three sections, we outline the limitations of existing symmetric models and net-effects thinking in relation to existing motivation performance relationship and suggest the use of a set-theoretic approach for more precise theory. We then propose a set-theoretic approach to leverage employee motivation for organizational performance to advance current thinking.

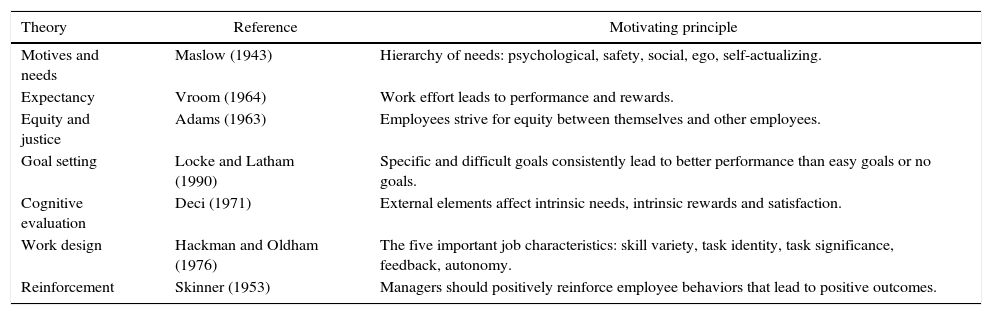

Employee motivation theoriesIt is hard to argue with empirical evidence that motivated employees mean better organizational performance (Nohria et al., 2008). There are several major theories that provide understanding of employee motivation: motives and needs (Maslow, 1943), expectancy theory (Vroom, 1964), equity theory (Adams, 1963), goal setting (Locke & Latham, 1990), cognitive evaluation theory (Deci, 1971), work design (Hackman & Oldham, 1976), and reinforcement theory (Skinner, 1953). Table 1 summarizes each motivation theory and their principles. We explain these motivation principles below.

Employee motivation theories.

| Theory | Reference | Motivating principle |

|---|---|---|

| Motives and needs | Maslow (1943) | Hierarchy of needs: psychological, safety, social, ego, self-actualizing. |

| Expectancy | Vroom (1964) | Work effort leads to performance and rewards. |

| Equity and justice | Adams (1963) | Employees strive for equity between themselves and other employees. |

| Goal setting | Locke and Latham (1990) | Specific and difficult goals consistently lead to better performance than easy goals or no goals. |

| Cognitive evaluation | Deci (1971) | External elements affect intrinsic needs, intrinsic rewards and satisfaction. |

| Work design | Hackman and Oldham (1976) | The five important job characteristics: skill variety, task identity, task significance, feedback, autonomy. |

| Reinforcement | Skinner (1953) | Managers should positively reinforce employee behaviors that lead to positive outcomes. |

According to Maslow, employees have five levels of needs (Maslow, 1943): physiological, safety, social, ego, and self-actualizing. Maslow argued that lower level needs are first satisfied before the next higher level need would motivate employees. Herzberg's work categorized motivation into two factors: motivators and hygienes (Herzberg, Mausner, & Snyderman, 1959). Motivator or intrinsic factors, such as achievement and recognition, produce job satisfaction whereas hygiene or extrinsic factors, such as pay and job security, produce job dissatisfaction. The interest in this theory peaked in the 1970s and early 1980s (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999).

Vroom's expectancy theory is based on the belief that employee effort will lead to performance and performance will lead to rewards (Vroom, 1964). Rewards may be either positive or negative. The more positive the reward the more likely the employee will be highly motivated. Empirical work on expectancy theory generated substantial interest in the 1960s but declined substantially in the 1990s (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999).

Adams's equity and justice theory states that employees strive for equity between themselves and other employees (Adams, 1963, 1965). Inequity comparisons result in a state of dissonance or tension that motivates an employee to engage in behavior designed to relieve tension (e.g., raise or lower work efforts to re-establish equity, leave the situation that is causing inequity). Although research focused on equity and justice theory experiences its ups and downs in popularity since introduced in the 1960s, it remains relevant today (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999).

Many reviews and meta-analyses of the goal-setting literature concluded that there is substantial support for the basic principles of goal-setting theory. Goal setting is most effective when there is feedback showing progress toward the goal. Specific difficult goals consistently lead to better performance than specific easy goals or no goals (e.g., Latham & Locke, 1991; Locke, 1996). As an overarching theory, goal setting continues as a very active area of research (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999).

Cognitive evaluation theory (Deci, 1971) is designed to explain the effects of external consequences on internal motivation. That is, intrinsically motivated employees attribute the cause of their behavior to internal needs and perform behaviors for intrinsic rewards and satisfaction. However, external elements (e.g., the reward system) may lead the employee to question the true causes of his/her behavior. Therefore, employees should be most intrinsically motivated in work environments that minimize attributions of their behavior to “controlling” external factors (Deci & Ryan, 1980). A majority of research published using cognitive evaluation theory is during the 1970s and 1980s (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999).

Work design is based on Hackman and Oldham's (1976) job characteristic theory, which incorporates five important job characteristics – skill variety, task identity, task significance, feedback, and autonomy – that result in positive employee and organizational outcomes, typically firm performance. Work design continues to be supported in empirical research and provides a useful framework for job design today (Ambrose & Kulik, 1999).

Skinner's reinforcement theory (1953, 1969) simply states those employees’ behaviors that lead to positive outcomes will be repeated, and behaviors that lead to negative outcomes will not be repeated. Managers should positively reinforce employee behaviors that lead to positive outcomes (e.g., with extrinsic rewards). Managers should negatively reinforce employee behavior that leads to negative outcomes (e.g., with performance feedback and/or punishment).

Each of these traditional theories informs researchers and managers about the specific elements and organizational levers used to motivate employees. For example, Maslow's hierarchy of needs specifies pay as one of the levers that motivate employees. Equity theory refers to fairness and justice among employees, while work design (job characteristic theory) is essential for a motivated high-performing workforce. Yet they take a modular approach that only explains isolated pieces of the broader holistic relationship between employee motivation and performance. Although many researchers try to reconcile and find common implications from these traditional theories (e.g., Rainlall, 2004), they neglect taking a holistic or systems view for a comprehensive theory that should incorporate research from other disciplines.

Current thinking on motivationIn attempts to develop a more comprehensive theory of employee motivation, researchers look to other disciplines for understanding. The aim of the current research is to bring together and evolve traditional motivation theories by developing a more comprehensive theory that encompasses not only the perspectives of management, human resources, and organization behavior, but also other relevant theories.

In a synthesis of cross-disciplinary research in fields like neuroscience, biology and evolutionary psychology, Lawrence and Nohria (2002) propose the “human drives” theory, which states that employees are guided by four basic emotional drives that are a product of common human evolutionary heritage: the drives to acquire, bond, comprehend, and defend. The researchers survey a financial service giant, a leading IT services firm and 300 Fortune 500 companies and find these four drives led to high levels of engagement, satisfaction, commitment and a reduced intention to quit, and ultimately better corporate performance.

The drive to acquire (Nohria et al., 2008) pertains to the acquisition of scarce goods that support an employee's sense of well-being. These goods include physical items such as food, clothing, housing and money, and also experiences like travel and entertainment. Social status, promotion, getting a corner office or a place on the corporate board also fulfills the drive to acquire. This drive tends to be relative in the sense that employees will always compare what they have with others. Therefore, employees always care not only about their own compensation packages, but also compensation packages relative to others’.

The drive to bond (Nohria et al., 2008) is associated with strong positive emotions like caring. This bond accounts for the enormous boost in motivation when employees feel proud of belonging to the organization, and for their loss of morale when the organization betrays them. This drive explains why employees become attached to their closest colleagues and find it hard to break out of divisional or functional silos. It also explains the ability for employees to form attachments to larger collectives and care more about the organization than about their local group within it.

The drive to comprehend (Nohria et al., 2008) centers around the need to satisfy employee curiosity and mastering the world around them. Employees want to take reasonable action and respond to organizational events as part of their desire to make a meaningful contribution. These employees are motivated by jobs that challenge them and enable them to grow, learn, innovate and contribute to their organization and their society, but are disheartened by jobs that are boring or lead to a dead end. Talented employees who feel trapped often leave their jobs to find new challenges elsewhere.

The drive to defend (Nohria et al., 2008) is derived from the natural defense of personal property, accomplishments, family and friends, ideas and beliefs against external threats. The result is a quest to create institutions that promote equity and justice, that have clear goals and intentions, and that allow employees to express their ideas and opinions. Satisfying the drive to defend leads to employees feeling secure and confident. Without this drive, employees show strong negative emotions like fear and resentment. This drive explains employees’ resistance to change, and the devastation that they feel when experiencing a merger or acquisition.

Lawrence and Nohria (2002) showed that an organization's ability to meet the four fundamental drives explain about 60% of employees’ variance on the motivational indicators of engagement, satisfaction, commitment and intention to quit. They also find that certain drives (i.e., the drive to acquire, bond, comprehend, or defend) influence some motivational indicators more than others. For example, fulfilling the drive to bond has the greatest impact on commitment, whereas meeting the drive to comprehend is most closely linked with engagement. They conclude that an organization can best improve overall motivation by satisfying all four drives together. At the same time, each of the four drives are independent in that they cannot be ordered hierarchically or substituted for one another. For example, you cannot pay employees a high salary and hope that they feel enthusiastic about their work when there is little bonding, or work seems meaningless, or when they feel defenseless. Therefore, to fully motivate employees, organizations and their managers must address all four drives. To fulfill all the four emotional drives, Nohria et al. (2008) suggest that each drive is best met by a distinctive organizational lever of motivation.

Organizational levers of motivationTo fulfill the drive to acquire, an organization must discriminate between good, average and poor performers by tying rewards clearly and transparently to performance and giving the best employees opportunities for advancement. This rewards system must provide competitive employee compensation relative to the industry. Lawrence and Nohria (2002) show that these reward systems improved employee engagement and satisfaction.

The drive to bond is fulfilled when a culture promotes teamwork, collaboration, openness and friendship. Management is encouraged to care about their employees, and employees are encouraged to care for each other so that there is a sense of collegiality and belonging. Employees are also encouraged to form new bonds.

Job design involves creating and specifying jobs that are meaningful, interesting and challenging to support the drive to comprehend. Employees are also challenged to think more creatively and broadly about how they could contribute to make a difference to the organization, customers, and investors.

The drive to defend is met when there is increased transparency, fairness and equity over all processes. To emphasize these characteristics, performance management and resource-allocation processes are used. These processes make evaluation and decision processes transparent, fair and clear.

The limitations of existing symmetric models and net-effects thinkingThe research by Lawrence and Nohria (2002) and Nohria et al. (2008) contribute greatly to developing a comprehensive motivation theory that incorporates many key research fields. However, we suggest that the theory concerning employee motivation and organization performance may be advanced by adopting an alternative research method approach over the conventional quantitative analysis on which current theories are based.

As it stands, researchers view their primary task as one of assessing the relative importance of causal variables drawn from the various employee motivation theories. In the perfect situation, the relevant theories emphasize different motivation variables and make clear and unequivocal statements about how these variables are connected to relevant outcomes. However, in practice, motivation theories are imprecise when it comes to specifying both causal conditions and outcomes, and they tend to be even more vague when it comes to stating how the causal conditions are connected to outcomes (i.e., what are the conditions that must be met for motivated employees and organizational performance? What are the justifications for the conditions chosen?). Therefore, researchers usually develop only general lists of potential relevant causal conditions, better known as contingent moderating and/or mediating variables, based on the broad definitions of what they find in competing motivation theories (Ragin, 2008). The main analytic task is typically viewed as one of assessing the relative importance of the relevant moderators and mediators. If the moderators/mediators associated with a particular motivation theory prove to be the best predictors of the outcomes (i.e., variables that provide the highest percentage of variance explained), then this model is used for informing existing theory or developing new theory. These models are symmetric by design and the correlation coefficient is the measure for developing conclusions based on general patterns of association (Ragin, 2008). This method of conducting quantitative analysis is the default procedure in the social sciences today, one that researchers fall back on, often for lack of knowledge of a clear alternative.

Specifically, in conventional quantitative research (e.g., multiple regression analysis, structural equation modeling), independent variables are seen as analytically separable causes of the outcome under investigation (Woodside, 2013). Typically, each causal variable is thought to have an independent capacity to influence level, intensity or probability of the dependent variable. These methods assume that the effects of the independent variables are both linear and additive, meaning that the impact of a given independent variable on the dependent variable is assumed to be the same regardless of the values of other independent variables (Woodside, 2013). This is known as net-effects estimation, which assumes that the impact of a given independent variable is the same not only across other independent variables but also across all their different combinations (Ragin, 2008). To estimate the net effect of a given independent variable, the researcher offsets the impact of rival causal conditions by subtracting from the estimate the effect of each variable any explained variation in the dependent variable it shares with other causal variables (Ragin, 2008; Woodside, 2013).

When confronted with arguments that cite combined conditions (e.g., that a recipe of some sort must be satisfied), the usual recommendation is that researchers model combinations of conditions as interaction effects and test for the significance of the incremental contribution of “statistical interaction” to explain variation in the dependent variable (e.g., Baker & Cullen, 1993; Drazin & Van de Ven, 1985; Miller, 1988). When there is interaction, the size of the effect of an independent variable on a dependent variable depends upon the values of one or more other independent variables. However, as explained in Ragin (1987, 2008), estimation techniques designed for linear-additive models often come up short when assigned the task of estimating complex interaction effects. Large samples are required, and there are still many controversies and difficulties surrounding the use of any variable in multiplicative interaction models (Ragin, 2008).

When used exclusively, Ragin (1987, 2000, 2008) points out the problem of symmetric models and net-effects thinking. First, the evaluation of net effects is dependent on model specification and can be swayed by the correlation among the moderating/mediating variables. Limiting the number of correlated variables and a chosen variable may have a substantial net effect on the outcome, but this variable may not have a net effect in the presence of other correlated variables (see also Woodside, 2013). Second, and most importantly, the estimation of net effects is highly dependent on the correct specification of the research model, and this is dependent upon strong theory and deep knowledge, which are often lacking in the application of net-effect methods. Therefore, how meaningful is a specified research model that does not have strong theory? And, how much credibility is there in the conclusions that are derived from the specified research model?

While powerful and rigorous, the net-effects approach is limited. Consequently, it is reasonable to consider an alternative approach, one with strengths that complement those of symmetric models and net-effects methods. In addition to assessing net effects, researchers could examine how different causal conditions among employee motivations combine to explain organizational performance. Specifically, the net-effects approach, with its heavy emphasis on calculating the effect of each independent variable in order to isolate its independent impact, can be counterbalanced and complemented with an approach using set theory that explicitly considers the combinations and configurations of various conditions.

Using a set-theoretic approach for more precise theorySince qualitative research involves understanding context and social occurrences holistically, researchers will tend to think in terms of combinations and configurations. Researchers will often think of causal conditions in terms of “causal recipes”, the causally relevant conditions that combine to produce a given outcome. This interest in combinations of causes can also provide an explanation for “how” things happen. Therefore, a configurational approach suggests that organizations are best understood as clusters of interconnected structures and practices, rather than as modular or loosely coupled entities whose components can be understood in isolation (Fiss, 2007, 1180).

According to Ragin (2008), the challenge posed by configurational thinking is to see causal conditions not as adversaries in the struggle to explain variation in dependent variables, but as potential collaborators in the production of outcomes. The key is not which variable has the biggest net effect, but how different conditions combine and whether there is only one combination or several different combinations of conditions (or causal recipes) capable of generating the same outcome. That is, a configurational approach supports the idea that causation may be complex and that the same outcome may result from different combinations of conditions. Once these combinations are identified, it is possible to specify the contexts that enable or disable specific causes. Therefore, the configurational approach takes a systemic and holistic view of organizational phenomena, where patterns and profiles rather than individual independent variables are related to performance outcomes (Delery & Doty, 1996; Drazin & Van de Ven, 1985).

Early forms of configurational approaches involved cluster analysis (e.g., Whittington, Pettigrew, Peck, Fenton, & Conyon, 1999). However, cluster analysis also has a number of limitations. For example, cluster analysis tends to treat each configuration as a “black box” insofar as only differences between constellations of variables can be detected. The analysis does not extend to the contribution of individual elements to the whole or to an understanding of how the variables combine to achieve the outcome (Ragin, 2000). This method also relies on research judgement to determine cutoff points for clustering, and results depend on the selection of the sample and variables, the scaling of the variables and the clustering method (Ketchen & Shook, 1996).

Instead of using symmetric models with interaction effects or clustering algorithms, a set-theoretic approach uses Boolean algebra to determine which combinations of organizational characteristics combine to result in a specified outcome (Fiss, 2007). Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) is often cited as an analytical approach and set of research tools to conduct detailed within-case analysis and formalized cross-case comparisons under the assumption of complex causality (Fiss, 2011; Legewie, 2013; Woodside, 2013). Complex causality means that: (1) causal factors combine with each other to lead to occurrence of a given type of phenomenon, (2) different combinations of causal factors can lead to the occurrence of a given type of phenomenon, and (3) causal factors can have opposing effects depending on the combinations with other factors in which they are situated (Wagemann & Schneider, 2010, 382). QCA's sensitivity to causal complexity give it an analytic edge over many statistical techniques of data analysis (Schneider & Wagemann, 2010, 400).

A set-theoretic approach to leveraging employee motivationThe research by Lawrence and Nohria (2002) and Nohria et al. (2008) made significant inroads to developing a comprehensive motivation theory. To fulfill all the four emotional drives to acquire, bond, comprehend and defend, Nohria et al. (2008) suggest that each drive is best met by a distinctive organizational lever – the reward system, culture, job design, and performance management and resource allocation processes, respectively.

However, the investigators perform conventional quantitative analysis on data derived from a survey of a financial service giant, a leading IT services firm and 300 Fortune 500 companies. The survey was developed from prior empirical research that were based on the various employee motivation theories. Lawrence and Nohria (2002) reference empirical work from almost all the motivation theories, incorporating the representative variables for employee motivation and the organizational lever for motivation, with all the potential relevant causal conditions in their survey. The effect of each variable is assumed to have an independent capacity to influence level, intensity or probability of organizational performance in a linear and additive way. In this symmetric design, correlation and other measures of association were used to estimate the net effects assuming that the impact of a given independent variable is the same not only across other independent variables but also across other independent variables and also across all their different combinations. To estimate the net effect of a given independent variable, the researchers offset the impact of competing causal conditions by subtracting from the estimate the effect of each variable of any explained variation in the dependent variable it shares with other causal variables.

An initial step to overcoming the deterministic nature of the Lawrence and Nohria (2002) and Nohria et al. (2008) comprehensive “human drives” theory on employee motivation, organizational levers and organizational performance is to understand the “level of influence” of the organizational levers. Reward systems, job design, and performance-management and resource allocations processes are microscopically focused levers that organizations can use to fulfill each respective drive, as long as they are specified correctly. That is, the reward system, job design and performance-management and resource allocation processes must be independently and specifically aligned with each drive. When there is no alignment, these levers do not lead to the fulfillment of their respective drives. This raises the following questions in our minds: Are the relationships between these organizational levers and employees’ drives truly binary and linear as prior research suggests? Even if a lever is aligned with a human drive, how can the failure of a lever be explained? In reality, we argue that there are circumstances that cannot be completely influenced and covered by a reward system, job design, and/or performance-management and resource allocation processes especially in the long term because they are microscopically focused on specific elements of “human drives”.

Similarly, fostering collaboration, teamwork, mutual reliance and friendship among employees through culture fulfills employees’ desire to bond. Yet the same argument above about influence and coverage applies, and while a team culture may fulfill a desire to bond, so could a culture of innovation where everyone is drawn together by a discovery, or a culture of bureaucracy where rules, policies and a stable environment could encourage mutual reliance and friendship. The difference between reward system, job design, performance-management and resource allocations process and culture is that culture is throughout an organization. Very often, an organization has built its brand and reputation on a type of culture. For example, Google is built on an innovation culture while Walmart is built on a culture that competes aggressively for market share in consumer spending.

To understand how various cultures may be used as an organizational lever that facilitates employee motivation, there is a need to identify the prevailing types of organizational cultures. Using a list of effectiveness criteria that was claimed by Campbell (1977) as comprehensive in scope, Quinn and Rohrbaugh (1983) discovered that values, assumptions and interpretations cluster together via multi-dimensional scaling. The framework specifies culture in terms of two sets of competing values: (1) the dilemma over flexible and control values, and (2) the dilemma over people (internal) and organizational (external) focus. Four types of cultures transpire from these two sets of competing values: flexible cultures that emphasize an internal or external focus, and control cultures that emphasize an internal or external focus. Flexibility encourages employee empowerment and creativity, and control aid implementation of the new ideas (Khazanchi, Lewis, & Boyer, 2007). The clan culture (hereafter team culture) places a great deal of emphasis on human affiliation in a flexible structure, internal focus on cohesion and morale, and human resource development to create team spirit (Cameron, Quinn, DeGraff, & Thakor, 2006). The adhocracy culture (hereafter innovation culture) places a great deal of emphasis on change through a flexible structure, external focus that requires a readiness to grow through risk-taking, innovation, planning and adaptability, resource acquisition and cutting-edge output (Denison & Spreitzer, 1991). The hierarchy culture (hereafter bureaucratic culture) places a great deal of emphasis on structure characterized by bureaucratic mechanisms that provide clear roles and procedures that are formally defined by rules and regulations. It is internally oriented, and stresses the role of information management, communication and routines to support an orderly work environment with sufficient coordination and distribution of information to provide employees with a psychological sense of continuity and security through conformity, predictability and stability (Quinn & Kimberly, 1984). Finally, the market culture (hereafter competitive culture) places a great deal of emphasis on control mechanisms in an externally focus structure. This culture values competition, competence, and achievement (Hartnell, Ou, & Kinicki, 2011). Clear objectives, goal setting, productivity and efficiency are rewarded (Cameron & Quinn, 1999). The competing values framework (CVF) is a culture taxonomy widely used in research (Cameron et al., 2006; Ostroff, Kinicki, & Tamkins, 2003).

Each type of culture is viewed as an organizational lever to fulfill the drives that motivate employees, thereby overcoming the binary and linear limitations as well as the incomplete coverage of specifying narrow levers using a reward system, job design, and performance-management and resource-allocation processes. For example, introducing some characteristics of an innovation culture may be sufficient to provide meaning to fulfill the drive to comprehend whereas, adopting some characteristics of a bureaucratic culture may provide the appropriate level of fairness and transparency to fulfill the drive to defend. Consequently, culture has a deeper level of influence because of the various types. This macroscopic property gives the many types of culture the potential to be organizational levers that subsumes the narrow levers to motivate employees over the long term.

Given the variety of cultures, we therefore pose the research question: What cultural levers best motivate employees to create organizational value? Prior research on organizational culture and value suggest that a configurational approach may be necessary to better understand the patterns between the antecedent conditions and outcomes within a type of culture rather the net effects of a specified culture on value (Hartnell et al., 2011). Therefore, we advocate that researchers use a set-theoretic approach to provide “causal recipes” of cultural conditions sufficient for motivating employees to create organizational value. Set-theoretic analysis focuses on uniformities and near uniformities of a set of conditions (variables), rather than on general patterns of association. Our understanding of employee motivation, organizational levers of motivation and organizational performance may be advanced by adopting this alternative approach over conventional quantitative analysis.