While the overall impact of COVID-19 is still being assessed, there is strong evidence that the pandemic has greatly aggravated traditional flaws of healthcare systems around the globe. Understanding the healthcare impact of the COVID-19 pandemic is essential for emergency preparedness and the prevention of collateral damage. The food and agriculture sector is an essential service and critical to food availability and access. However, literature on the healthcare impact of COVID-19 in farmers is scarce. This study aimed to explore healthcare delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in certified organic producers.

MethodsAn observational Cross-sectional study based on answers of an electronic self-reported survey. Participants included were United States certified organic producers listed in the Organic Integrity Database.

ResultsRespondents represented 40 states; response rate was estimated at 11%. Analyses were conducted on 344 records. A high majority were non-Hispanic Whites with a four-year college education or more. More than 90% had health insurance. More than one-third (36.5%) of respondents reported healthcare delays. Female producers were nearly twice as likely to report non-COVID-19 related healthcare delays as their male counterparts (OR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.10–3.44).

ConclusionThis study provides national data on healthcare delays among organic producers and their households and identifies sex differences in non-COVID-19 related healthcare delays. This study is the first to collect data on organic producers and can serve as a baseline for future studies; it may inform practice, research and policy on emergency preparedness, protection of essential workers, and healthcare services and quality.

La COVID-19 ha agravado las limitaciones tradicionales de los sistemas de salud a nivel global. Entender el impacto de la pandemia es fundamental para prepararse ante futuras emergencias y prevenir sus posibles efectos colaterales. Aunque la COVID-19 ha mostrado que la agricultura es esencial en la producción y disponibilidad de alimentos, hay muy poca literatura sobre el impacto de la pandemia en trabajadores del campo. El objetivo de este estudio fue explorar el efecto de la COVID-19 en agricultores orgánicos certificados.

MétodosEstudio observacional de corte transversal de las respuestas obtenidas mediante cuestionario en papel y electrónico. La población de estudio consistió en productores orgánicos certificados de Estados Unidos registrados en el Organic Integrity Database.

ResultadosAgricultores de 40 estados participaron en el estudio, con respuesta estimada al 11%. Los análisis se realizaron en un total de 344 registros. La mayoría de los participantes fueron blancos no hispanos con cuatro años o más de educación universitaria, más del 90% tenían seguro de salud. Más de un tercio (36,5%) declararon retrasos en servicios asistenciales, las mujeres con casi el doble de probabilidades de reportar retrasos comparadas con los hombres (AOR 1,95, IC 95%: 1,10-3,44).

ConclusiónEl estudio proporciona datos sobre retrasos en asistencia sanitaria no relacionados con la COVID-19 entre productores de alimentos orgánicos y allegados, e identifica diferencias de género. Este estudio, el primero en proporcionar datos sobre agricultores orgánicos, puede servir de base a futuros estudios e informar las intervenciones, investigaciones y políticas de preparación ante emergencias, protección de trabajadores esenciales, asistencia sanitaria y calidad de servicios.

The current COVID-19 pandemic is revealing the tremendous stress that an easily transmitted virus can place on healthcare. In early December 2021, the World Health Organization (WHO) confirmed 262 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 5 million deaths.1 By the same date in the United States (US), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported more than 48 million cases and 780,000 deaths. COVID-19 related hospital admissions between August 2020 and early November 2021 totaled more than 3.2 million.2 Later in 2021, the Delta, Omicron and other potential variants continued to challenge already exhausted healthcare systems.

In June 2020, WHO published specific recommendations for maintaining essential health services.3 However, the surge of the pandemic greatly aggravated the flaws of healthcare systems around the globe, and soon after countries started to experience critical difficulties in maintaining essential services. Global 2020 data indicated that in a period of 12 weeks, more than 28 million scheduled surgeries were canceled due to COVID-19 in reporting countries.4 Both hospital admissions and emergency room visits for injuries and acute and chronic illnesses decreased5,6; vulnerable patients with mental health conditions and those with weakened immune systems, such as cancer patients, were particularly affected worldwide.7,8 Childhood immunization and secondary prevention programs were disrupted in every country, and in early 2021 WHO reported that nine out of 10 countries had experienced disrupted essential health services.4

When health systems are overwhelmed both direct mortality from an outbreak and indirect mortality from treatable conditions increase dramatically, including premature death caused by delayed or inappropriate care.3 While a well-prepared system has the capacity to maintain proper access to all services, COVID-19 demands for acute and long-term care have challenged even the most developed universal health systems. This is due to many factors, such as reduced availability of specialists and therapists; restrictions on referrals; high risk of infection at hospitals and other health services; and reallocation of human, material, and financial resources to attend to the healthcare demand of the pandemic. When COVID-19 began to spread, specialists stopped seeing new patients and elective surgeries and diagnostic procedures were canceled. In the US and many other countries, early data indicated that minoritized and racialized populations were disproportionally being affected by COVID-19 in terms of prevalence, treatment and mortality.9,10 Similarly, a US survey by the Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) showed that women's work and family dynamics were disproportionately impacted by the pandemic.11

COVID-19 and workers, essential workersWhile literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic continues to emerge, the extent of the collateral damage in the workforce is still unknown. Most studies assessing the impact of the pandemic in workers focus on essential workers, particularly healthcare providers. However, COVID-19 has made more evident that the definition of essential workers is broad.

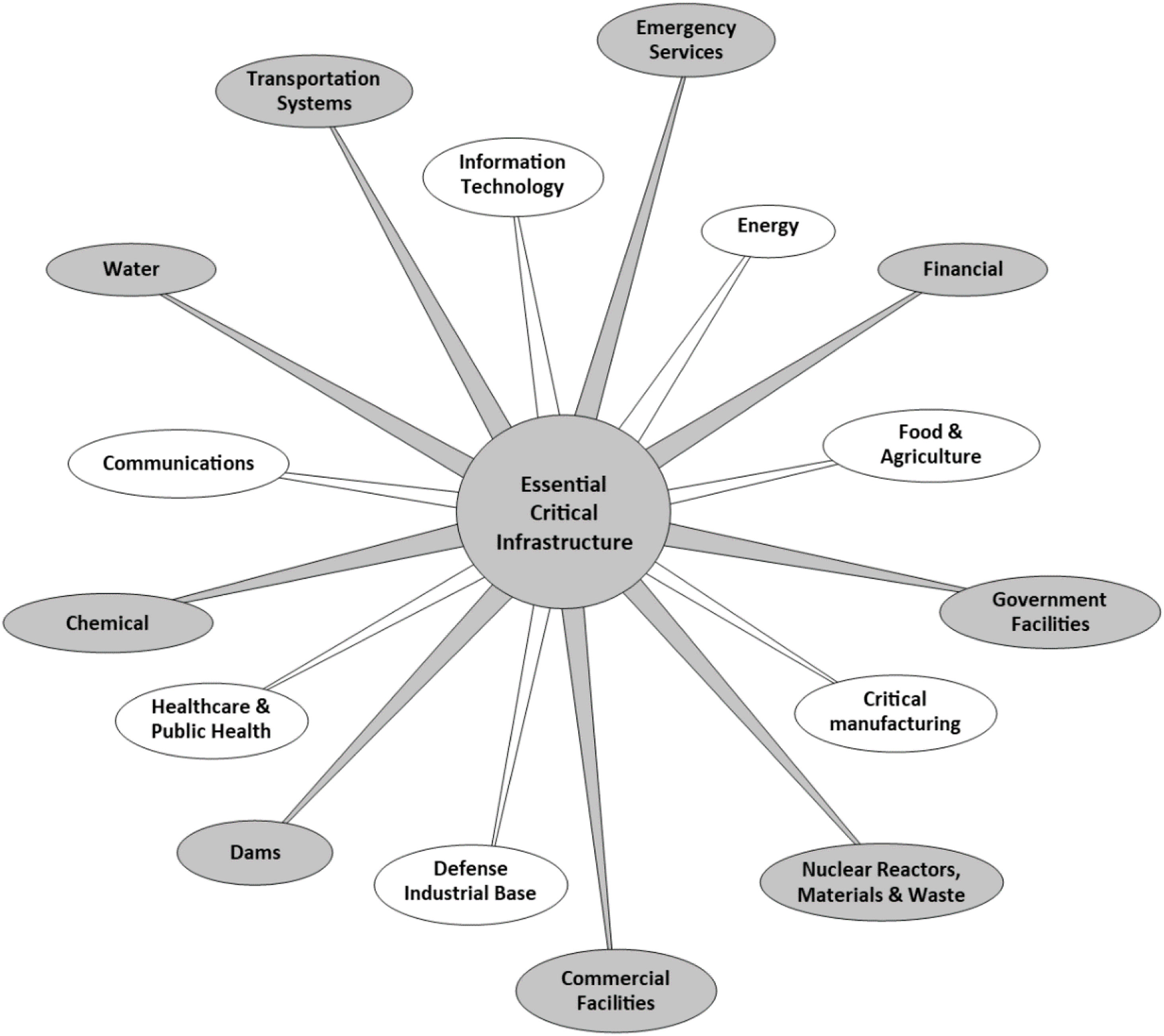

In the US, the Department of Homeland Security recently defined essential workers as those conducting operations and services essential to critical infrastructure. These workers represent industries as diverse as medical and healthcare, telecommunications, information technology systems, defense, transportation and logistics, energy, water and wastewater, law enforcement and food and agriculture (Fig. 1).

While healthcare workers face more exposure to the virus, a diversity of industries and occupations have been severely affected by COVID-19 including food and transportation.10,12

COVID pandemic, food and agricultureThe food and agriculture sector is an essential service and critical to food availability and access. In the US, the media covering the COVID-19 pandemic first focused on meat processing workers and early data confirmed multiple outbreaks among meat and poultry processing facility workers. The Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) attempted to address the situation by issuing an Interim Guidance on meat and poultry processing workers and employers.13 Soon after, it was realized that the entire food chain, from production to consumption, was severely affected by the pandemic.

The actual impact of the COVID pandemic on US farmworkers is still being assessed, and only limited and inconsistent data on infection rates in agriculture exist. Using data by Purdue University Food and Agriculture Vulnerability Index, researchers conservatively estimated more than 727,000 positive COVID-19 cases among agricultural workers nationally, or 9.4% of all agricultural producers, hired workers, unpaid workers and migrant workers.14 A lower infection rate (6.4%) was estimated by a national study of organic producers15; and a local study on farmworkers in central California reported a significantly higher prevalence, 22%.16

The organic farmer and COVID-19The popularity of organic agriculture continues to grow. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) database on certified organic operations lists more than 45,000 certified organic operations worldwide, with approximately 62% of them (or 28,000+ farms) located in the US.17 Organic products are now available in practically every US conventional grocery store. According to a 2018 study by the Pew Research Center, 40% of US adults said that most or some of the food they eat is organic.18 The USDA describes organic agriculture as farming practices that conserve biodiversity and promote and support ecological balance.

Despite the significant growth, current national surveillance systems do not provide data on the individual and contextual factors that may determine the health and well-being of the organic farmer.19,20 This gap in data makes it more difficult to assess the overall impact of COVID-19 in a population that has shown to be essential to alleviate the effects of the pandemic on the food supply chain. Since most organic farms are small and local, it has been suggested that they may be even more essential for communities to withstand, overcome, and recover from adversity, including a global pandemic.21

With consumers’ increasing reliance on local products, it is important to understand how the COVID-19 pandemic affected the healthcare of local producers. This study aimed to explore the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare delays among US certified organic producers and their household.

MethodsWe conducted an observational cross-sectional study based on answers from survey send to organic producers, which was integrated into an ongoing project that explores the occupational, psychosocial and contextual factors that contribute to injury and disease prevention in this population. More background information on the original project was provided in a previous publication.15 The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of New Mexico. All participants were provided with an informed consent form and voluntarily consented to participate.

Participants and eligibilityParticipants included US organic producers listed in the USDA Organic Integrity Database (OID). The USDA defines the farm producer as “the person who runs the farm, making day-to-day management decisions for the farm operation. She/he may be the owner, a member of the owner's household, a hired manager, a tenant, a renter, or asharecropper” (https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2017/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_US/usappxb.pdf). Inclusion criteria consisted of: (a) 18 years of age or older, (b) currently operating an organic farm in the US, and (c) listing a valid postal address or email address in the OID. Excluded were operations that solely engaged in processing organic consumer products.

The OID is a publicly available electronic database of certified organic operations. It includes a variety of operations (e.g. crop, handling, livestock, and wild crops) and certification status (e.g. certified, surrendered, suspended, revoked, and other). Contact information includes name (operator), phone, mailing address, and an optional entry for email address.

RecruitmentAn advanced search of the OID database returned over 27,000 operations. Since a primary recruitment approach was email, we prioritized those listing an email address. This resulted in a sample of 3559 farms. Recruitment began in fall 2020 and extended through spring 2021. Operators with an email address were sent an introductory message on the study and survey and a link providing a copy of the informed consent and access to the electronic survey. A portion of those without an email address or who had not completed the electronic survey (approximately 10% of the total sample) were reached by postal mail through a packet containing IRB documents, the paper survey and a stamped self-addressed return envelope. Recruitment efforts also included dissemination through websites, social media outlets, and through partners such as extension agents and farmer organizations. Reminder emails, phone calls and postcards were systematically sent to non-responders throughout the recruitment period. Participation incentives included $25, $50 and $100 merchandize cards from a national hardware and home improvement store.

SurveyThe data collection tool was developed by the research team through a process that included: (a) a search of the literature to identify domains of potential interest; (b) reiterated draft versions of the survey; and (c) a review by experts in public health, social and behavioral sciences, epidemiology, occupational health, and agricultural research. This process contributed to the face and content validity of the instrument. The final version of the survey consisted of 28-items, including standard sociodemographic questions and a COVID-19 specific item on healthcare delays (“Have you or anyone in your household experienced delays in healthcare unrelated to COVID-19 -regular check-up, diagnosis, treatment, surgery, or other medical procedures?”). Response option was binary yes/no.

Data collection and managementREDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture), a secure web application was used for data collection and management. Participants were assigned a unique ID number. Paper survey data were manually entered into REDCap by trained project staff. Those who did not meet qualifying questions, did not provide answers to sociodemographic questions or the COVID-19 item were classified as “incomplete” and excluded from the analysis. Cases were excluded from the logistic regression analysis if they did not have valid data for all variables included in the model. The question about COVID-19 prevalence was dichotomized for inclusion in the logistic regression model to reflect whether the respondent and/or someone in their household had had a confirmed case of COVID-19.

Data analysisWe used SPSS 25.0 (IBM SPSS Statistics, Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) to analyze the data. We conducted descriptive and bivariate analyses of all sociodemographic characteristics, COVID-19 prevalence among respondents and household members, and experiences of healthcare delays. We conducted a logistic regression analysis to assess the extent to which prevalence and having healthcare insurance are associated with the likelihood of experiencing healthcare delays for females and males when adjusting for sociodemographic characteristics.

ResultsSurveys from 387 participants representing 40 states were collected, for an estimated response rate of 11%. Texas, New Mexico and New York had the highest response rates, 12.9%, 12.1% and 10%, respectively. Analyses were conducted on 344 records, after excluding incomplete surveys. Slightly more than a third of respondents identified as female and nearly half were 55 years old or older. A high majority were non-Hispanic Whites born in the US. Two thirds reported having a four-year college education or more, half lived in a household with two or more people, and more than 80% were married or cohabitating. More than 90% had health insurance and nearly one-third had a yearly household income under $50,000. About half were new or beginning organic farmers and had a farm size of at least 50 acres (Table 1).

Social demographic and selected characteristics of respondents.

| N | Percentage | Overall studied sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 55 years of age or older | 171 | 49.7% | 344 |

| Sex | |||

| Female | 118 | 34.4% | 343 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||

| Hispanic or Latino | 16 | 4.7% | 304 |

| Non-Hispanic White | 288 | 89.7% | 321 |

| Place of birth | |||

| USA | 330 | 96.8% | 341 |

| Education level | |||

| 4-Year degree or more | 232 | 67.8% | 342 |

| Annual household income | |||

| $50,000 or more | 245 | 73.8% | 332 |

| Household size | |||

| 2 or more other people | 174 | 50.9% | 342 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married or cohabitating | 287 | 83.9% | 342 |

| Years in organic Ag | |||

| More than 10 years | 163 | 47.5% | 343 |

| Acreage | |||

| At least 50 acres | 166 | 49.1% | 338 |

| Health insurance status | |||

| Health insurance | 312 | 91.0% | 343 |

The self-reported prevalence of a COVID-19 diagnosis by a healthcare provider among producers and household members was 9.6%; more than one-third (36.5%) of respondents reported non-COVID-19 related healthcare delays (Table 2). Associations between COVID-19 diagnoses, social demographic characteristics, and experience of healthcare delays were explored; only one demographic characteristic, being female, was correlated with self or household healthcare delays. Overall, 44% of female producers reported non-COVID-19 related healthcare delay, compared to 32.3% of male producers (p=0.031).

Prevalence of COVID-19 diagnoses among respondents and household members and delays in non-COVID-19 healthcare among respondents and household members.

| N | Percent | Overall studied sample | |

|---|---|---|---|

| COVID-19 prevalence | |||

| Respondent | 8 | 2.3% | 344 |

| Someone in household | 11 | 3.2% | 344 |

| Respondent & someone in household | 14 | 4.1% | 344 |

| Healthcare delays | |||

| Respondent or someone in household experienced delay getting healthcare unrelated to COVID-19 | 125 | 36.5% | 342 |

In the logistic regression analysis, female producers were nearly twice as likely to report non-COVID-19 related healthcare delays as their male counterparts (AOR 1.95, 95% CI: 1.10–3.44). No other demographic or farm characteristics had a statistically significant relationship with experiencing healthcare delays. When controlling for sex, marital status had a statistically significant association with healthcare delays for females but not males (Table 3). Among females, those who were married or cohabitating were eight times more likely to report healthcare delays than those who were not married (AOR 8.21, 95% CI: 1.69–39.80). No demographic or farm characteristic variables had a statistically significant association with healthcare delays for males (Table 4).

Odds of experiencing delays in non-COVID-19 healthcare experienced by organic producers.

| OR* | 95% CI | p-Value** | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respondent and/or family member had COVID-19 | 0.87 | 0.34–2.19 | 0.760 |

| Any type of health insurance | 1.93 | 0.67–5.62 | 0.225 |

| Sex – female | 1.95 | 1.10–3.44 | 0.022 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic | 0.55 | 0.10–3.12 | 0.502 |

| Race – non-Hispanic white | 0.67 | 0.19–2.41 | 0.538 |

| Born in US | 0.64 | 0.13–3.05 | 0.572 |

| Age – 55 years or over | 1.12 | 0.63–2.00 | 0.700 |

| Education level – 4-year degree or more | 1.36 | 0.73–2.55 | 0.338 |

| Marital status – married or cohabitating | 1.70 | 0.75–3.85 | 0.207 |

| Household size – 2 or more other people | 0.81 | 0.45–1.43 | 0.461 |

| Annual household income – $50,000/year+ | 0.91 | 0.49–1.70 | 0.766 |

| Years in organic farming – more than 10 | 0.79 | 0.46–1.36 | 0.385 |

| Farm size – 50 or more organic acres | 1.59 | 0.91–2.78 | 0.107 |

Odds of experiencing delays in non-COVID-19 healthcare experienced by organic producers by sex.

| Females | Males | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR* | 95% CI | p-Value** | OR* | 95% CI | p-Value | |

| Respondent and/or family member had COVID-19 | 3.72 | 0.36–38.45 | 0.271 | 0.57 | 1.18–1.84 | 0.345 |

| Any type of health insurance | 4.60 | 0.42–50.39 | 0.212 | 1.39 | 0.40–4.83 | 0.604 |

| Ethnicity – Hispanic | 0.99 | 0.02–51.32 | 0.995 | 0.59 | 0.07–4.85 | 0.626 |

| Race – non-Hispanic white | 0.87 | 0.09–8.13 | 0.900 | 0.63 | 0.13–3.15 | 0.573 |

| Age – 55 years or over | 1.70 | 0.58–4.99 | 0.335 | 1.40 | 0.67–2.93 | 0.369 |

| Education level – 4-year degree or more | 0.78 | 0.21–2.83 | 0.701 | 1.48 | 0.69–3.18 | 0.319 |

| Marital status – married or cohabitating | 8.21 | 1.69–39.80 | 0.009 | 0.64 | 0.23–1.78 | 0.391 |

| Household size – 2 or more other people | 0.50 | 0.17–1.48 | 0.207 | 1.13 | 0.55–2.33 | 0.737 |

| Annual household income – $50,000/year+ | 0.43 | 0.15–1.25 | 0.119 | 1.26 | 0.54–2.97 | 0.592 |

| Years in organic farming – more than 10 | 0.51 | 0.18–1.46 | 0.211 | 1.02 | 0.52–2.00 | 0.962 |

| Farm size – 50 or more organic acres | 2.58 | 0.94–7.12 | 0.066 | 1.19 | 0.59–2.38 | 0.632 |

This study aimed to explore the extent of healthcare delays caused by the COVID-19 pandemic on US certified organic producers and their families. It contributes survey data to a limited body of literature on the healthcare impact of the pandemic on essential workers.

Participants’ demographic characteristics are similar to those reported by national surveillance systems such as the 2017 Census of Agriculture-Organic Agriculture and the 2019 Organic Survey: age 55 years or older, predominantly White, non-Hispanic males, and with a high level of education. More than half reported less than 10 years of experience in organic agriculture, and 9% reported not having health insurance (Table 1).

COVID-19 self-reported prevalence by participants in this study was previously reported15 and was estimated at 6.4%. This is significantly lower than that estimated by other researchers among farmworkers16 and agricultural producers14 (22% and 9.5% respectively). As of December 2021, overall COVID-19 prevalence in the US was at about 14%.2

On receiving healthcare, nearly 40% reported delays in getting care for issues unrelated to COVID-19 for themselves or someone in household (Table 2). Although the real impact of the pandemic on morbidity and mortality is still unknown, a high percentage of participants in this study reported experiencing disruption in healthcare services. This percentage is consistent with delays among adults reported in the US.22 Studies looking at reasons for delays in seeking and receiving healthcare and treatment include a combination of personal, community, and healthcare-system level factors such as access to medication.23,24 Future studies should quantify the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic in health status and unrelated mortality.

Of relevance is that female producers, and those who were married or cohabitating were more likely to report non-COVID-19 related healthcare delays. This result may be explained by household structure and sex differences in healthcare utilization. The household environment determines the distribution of roles, and the family system impacts the health and wellbeing of its individual members and the household as a whole. Within the family, mothers are still perceived to be the main person responsible for the health of the family, particularly children and their partners.25,26 The fact that more female participants in this study reported healthcare delays may relate to them being more aware of the issue, compared to male respondents.

Regarding healthcare utilization, while men and women report fair and poor health at similar rates (around 15%), national data indicate that women are more likely than men to see a provider and have higher medical care service utilization.27 It is likely the case that those who more regularly used healthcare services were more impacted by a severely compromised healthcare system. There is evidence that COVID-19 has exacerbated gender-based disparities in health and healthcare and resulted in collateral damage to women's health. A recent study in the US found more than 80% declines in breast and cervical cancer screening tests in April 2020 compared with the previous 5-year averages for that month.28 Globally, a systematic review and meta-analysis concluded that the COVID-19 pandemic increased maternal depression and deaths.29 and other reports and studies found that COVID-19 confinement measures have resulted in increased violence against girls and women.30,31 However, data and literature on healthcare delays and collateral damage caused by the COVID-19 pandemic is scarce and more research is needed.

The study has some limitations. Although the sample was small and it may not represent the entire US organic producer population, demographic characteristics of respondents parallel well-established agricultural surveillance systems. Response rate was low but typical of similar survey studies. Data were self-reported, which may reflect respondents’ personal biases. However, self-reported questionnaires are widely used and validated in observational studies. Those who experienced COVID may have been more motivated to participate, which would skew data on prevalence and healthcare delays. Nevertheless, our results are consistent with other national studies. The item on healthcare delays was inclusive of both the respondent and their household, and had a yes/no binary response scale. Results apply to household rather than the individual participant. We acknowledge that while this study did not directly explore quality of care, delays in service may have a negative impact on healthcare quality.

ConclusionsThis study provides national data on healthcare delays among organic producers and identifies sex differences in non-COVID-19 related healthcare delays. While the results of the study are consistent with emerging literature on the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare utilization, this self-reported cross sectional study is the first to collect information on organic producers and can serve as a baseline for future studies. This study may inform practice, research and policy on emergency preparedness, protection of essential workers, and healthcare services and quality.

FundingThis project was supported by: (1) The Southwest Center for Agricultural Health, Injury Prevention, and Education through Cooperative Agreement # U54-0H007541 from CDC/NIOSH; and (2) Grant No. 2U540H007541-16 from the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of The University of Texas Health Sciences Center at Tyler or the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest to disclose. No commercial or proprietary interest to declare.

Thank you to Dr. Andrew Rowland who advised this team to pursue a COVID-19 study. The authors also acknowledge contributing members of the team, Research Assistants Gabriel Gaarden, Morgan Stein, Amber Gonzales, Kaski Suzuki, Karaleah Garcia and Mercy Jones.