Several studies have shown that personality traits are a benchmark in research field of bullying prevention, while others have highlighted that the socio-emotional skills are important to prevent a wide range of maladjusted behaviors, suggesting that the investment in their developing may mediate the effects of personality dispositions. The present study aims to clarify if socio-emotional attitudes can mediate the relationships between personality traits and bullying.

MethodsFive sequential mediation models are tested using the Big Five personality traits as focal predictors, bullying as the outcome, and trait emotional intelligence and empathy as causally chained mediators, involving 199 primary school children (8-10 years) through the Bullying Prevalence Questionnaire, the Big Five Questionnaire for children, the Emotional Intelligence Index and the Empathy-Teen Conflict Survey.

ResultsData showed that openness, conscientiousness, and agreeableness were inversely related to bullying, and that the causal chain of TEI-empathy negatively and completely mediated the relationship between emotional instability and bullying and negatively and partially mediated the relationship between openness and bullying.

ConclusionsThese results suggest that TEI and empathy mediate the relationship between personality traits and bullying, reducing the risk of being involved in bullying perpetration.

Bullying is as complex phenomenon in which several actors are involved (Olweus, 1978; 2013). Although the school context is expected to be a safe space for education, socialization and protection, actually it is one of the places where bullying and violence can be mostly perpetrated (Hymel & Swearer, 2015). Several meta-analyses report different levels of involvement in bullying episodes across age, countries and gender (Papamichalaki, 2021).

Previous studies have investigated bullying perpetration and related aspects among children and adolescents using a variety of explanatory variables, including individual and contextual predictors (Xue et al., 2022). A valuable theoretical model that has focused mainly on individual predictors of bullying, particularly by investigating the link between personality traits and aggressive behavior, including bullying, is the Five Factor Model (Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015). According to the FFM, personality is composed by five traits: 1) neuroticism, which involves a generalized predisposition to emotional instability, being people characterized by anxiety, insecurity and fearfulness (Goldberg, 1990), and by failure avoidance; 2) extraversion, which reflects the tendency to be energetic, active, ambitious, and assertive (Feist, 1998); 3) conscientiousness, which refers to the tendency of being organized and working hard in order to achieve a goal (Goldberg, 1993); 4) agreeableness, which involves friendliness, in terms of affiliation, cooperation and supportive behaviour (Feist, 1998); 5) openness to experience, which relies on predisposition toward open-mindedness, intellectual curiosity, aesthetics, imagination, and creativity (Feist, 1998).

The meta-analysis by Mitsopoulou and Giovazolias (2015) has confirmed that bullies show low agreeableness and conscientiousness, high extraversion and neuroticism, and unexpectedly also lower openness. In addition, it appears that age moderated negatively the relationships between neuroticism and bullying, as well as gender moderated extraversion, where bully boys appeared to be more extroverted than bully girls. Taken together, this evidence shows that the relationships between the FFM and bullying are rather complex and need to be deepened.

Interestingly, another line of research is focused on the relationship between bullying and socio-emotional competencies, which play a key role in social and prosocial development (Kokkinos & Kipritsi, 2012). Emotional intelligence (EI) is generally seen as an ability or as a trait (Xu et al., 2019) conceived as a constellation of emotion-related self-perceptions and dispositions, which rely at the lower levels of personality hierarchies (Petrides et al., 2007; Russo et al., 2012).

TEI has been found positively related to extraversion, conscientiousness, agreeableness and openness, and negatively with neuroticism in children and preadolescents (Russo et al., 2012). Research on children has suggested that higher TEI levels predict improved wellbeing, positive social interactions (see Andrei et al., 2014), adaptive and pro-social behaviors (Frederickson et al., 2012; Mavroveli et al., 2009). Moreover, TEI has been found negatively related to bullying (Peachey et al., 2017) and children who acted bullying or cyberbullying behaviours declared to be unskilled in managing their emotions and those of others (Baroncelli & Ciucci, 2014).

In addition, empathy, defined as the ability to share emotional experience with others (Gilet et al., 2013), is another relevant factor in this scenario. Although empathy and TEI should be considered as distinct domains (Fernández-Abascal & Martín-Díaz, 2019) they are interrelated in their functioning (Petrides and Furnham, 2001). Indeed, children with higher emotional awareness, tend to show more empathic and pro-social behaviours (Finlon et al., 2015). Although TEI is associated and predicts empathy, these two factors are not completely overlapped (Kokkinos and Kipritsi, 2012; Fernández-Abascal and Martín-Díaz, 2019; Szabo & Bereczkei, 2017).

According to the above mentioned literature, studies have been principally interested to observe the association between personality traits and bullying (Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015), or between personality traits and TEI (Russo et al., 2012) and between personality traits and empathy (Melchers et al., 2016); other studies have investigated the association between bullying and TEI (Mavroveli et al., 2009); and still others have investigated the association between TEI and emphaty ((Kokkinos and Kipritsi, 2012). However, there are still a few studies that have investigated the mediating role of TEI and empathy in the association between personality and bullying.

Therefore, despite the extensive literature available, there is still no shared perspective on the relationship between personality traits, TEI and empathy. With respect to the personality traits, most studies seem to agree that they are associated with empathy, and that agreeableness appears the most predictive factor of empathy (Melchers et al., 2016). Accordingly, these results led us to assume that global TEI and global empathy are two possible mediators, positively chained together in a specific sequence in the explanation of the relationship between the FFM and bullying behaviours.

In light of these considerations and according to the theoretical framework of the FFM, the present study aims to investigate the associations among personality traits and socio-emotional skills involved in bullying. In particular, the extent to which the relationships between personality traits measured by the FFM, and bullying perpetration is mediated by the relationship between TEI and empathy is explored in a sample of primary school children. In line with the previous studies, we expected to find that the TEI-empathy causal chain is a possible mediator of the relationship between the considered personality traits and bullying.

MethodsParticipantsFor the present study the minimum required sample size was computed using an a-priori power analysis by the G*Power 3.1.9.7 software (Faul et al., 2007). Given that no previous study directly investigated the sequential mediation of TEI and empathy in the relationships between the FFM and bullying, following the recommendation of Faul et al. (2009), the default parameters were used. This procedure to use the default parameters to compute the required sample size was adopted in many other studies based on mediation analyses (see Qasim et al., 2021; Scrima et al., 2022). Specifically, the following parameters were used: “F test analysis” as test family; “Linear multiple regression: fixed model, R2 deviation from zero” as statistical test; “A priori: Compute required sample size – given α, power and effect size” as type of analysis; then, α err probability was set at 0.05; power (1-β err prob) was set at 0.95; the mean effect size f2 was set at 0.15 (medium effect); finally, the number of predictors entered were 5 (the focal predictor, that is one of the personality traits, TEI, empathy, and the two covariates gender and age). This model showed a required total sample size equal to 138. In this study a sample of 206 children was used, meeting and exceeding the required sample size. Children (57.3% females) aged between 8 and 10 (M = 9.17; SD= .79) were recruited on a voluntary basis from 3-4-5 classes of an Italian primary school located in Mondragone city in Campania region (Italy). All children were Italian native speakers and attended the primary school, with no neurological conditions, and no emotional or behavioural problems. Participation in this research was voluntary and data were collected anonymously. A signed informed consent was obtained from parents. The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the University of Zurich, as part of a larger study, and carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Materials and procedureA short questionnaire was administered online during school time to collect information about gender, age and general health. Then, four self-report questionnaires were administered in random order.

The Bullying Prevalence Questionnaire – BPQ (Fossati et al., 2012; Rigby & Slee, 1993) which consists of 20 items divided into subscales (6 items for bullying, 6 for victimization, 4 for pro-sociality, 4 filler items). For each item children were asked how often it was true of them, using a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 = Never, to 4 = Very Often). In this study only the bullying subscale was used (Cronbach's α = .65), providing an acceptable reliability (Taber, 2018).

The Big Five Questionnaire for children – BFQ-C (Italian version, Barbaranelli et al., 2003) which is a 30-item short version (6 item for each trait) of the 65-BFQ-C (Barbaranelli et al., 2003), aimed to assess five personality traits: openness, conscientiousness, energy/extraversion, agreeableness and emotional instability. Each item was evaluated along a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 “very false for me” to 4 “very true for me”). In this study the reliability of each scale was as follows: openness: Cronbach's α = .86; conscientiousness: Cronbach's α = .69; energy (extraversion): Cronbach's α = .70; agreeableness: Cronbach's α = .65; emotional instability: Cronbach's α = .72. These reliabilities can be considered acceptable (Taber, 2018).

The Emotional Intelligence Index - I-IE (Italian version; Veltro et al., 2016) which is a 15-item self-report scale designed to assess TEI using a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 “Never”; to 4 “Always”). The scale includes five subscales: intra-psychic, inter-personal, impulsivity, adaptive coping and self-efficacy . In this study the reliability of the general I-IE was:Cronbach's α = .80.

The Empathy-Teen Conflict Survey (Bosworth and Espelage, 1995; Dahlberg et al., 2005) which was adapted in Italian using the back translation procedure, and consist of 5 items to assess global empathy using a 5-point Likert scale (from 0 “Never”; to 4 “Always”). In this study the reliability was: Cronbach's α = .72.

ResultsAnalyses were carried out using IBM SPSS Statistics softwarev.34 (2016). Data were first checked for the presence of bully-victims children. No child scored high in both bullying and victimization subscales. Then, data were checked for outliers considering a cut-off of ±3 standard deviations away from the mean. Following Clark et al. (2012), univariate outliers across multiple variables were removed, as well as univariate outliers on the personality, TEI and empathy predictors were removed, whereas univariate outliers on the bullying score were included. In total, 7 outliers were detected and excluded from subsequent analyses. Thus, data for 199 children were tested for normality using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov Test (Z-Bullying = .215, p < .001; ZEmotional Instability =.079, p < .01; ZEnergy (Extroversion)=.142, p < 001; ZOpenness= .118, p < .001; ZConscientiousness =.128, p < .001; ZAgreeableness=.083, p < .01; ZTEI = .073, p < . 05; ZEmpathy = .081, p < .01) showing that all variables were not normally distributed. Therefore, correlational analyses were performed using Spearman's Rho. Means, standard deviations, and correlational analysis are shown in Table 1, for each variable of interest, including gender and age. Given that age was not correlated to bullying, only the covariate gender was included in the subsequent mediation analyses.

Means, standard deviation, and inter-correlations (Spearman's Rho).

Note. ** p < .01 (two tailed); * p < .05 (two tailed); N = 199; TEI = Trait Emotional Intelligence.

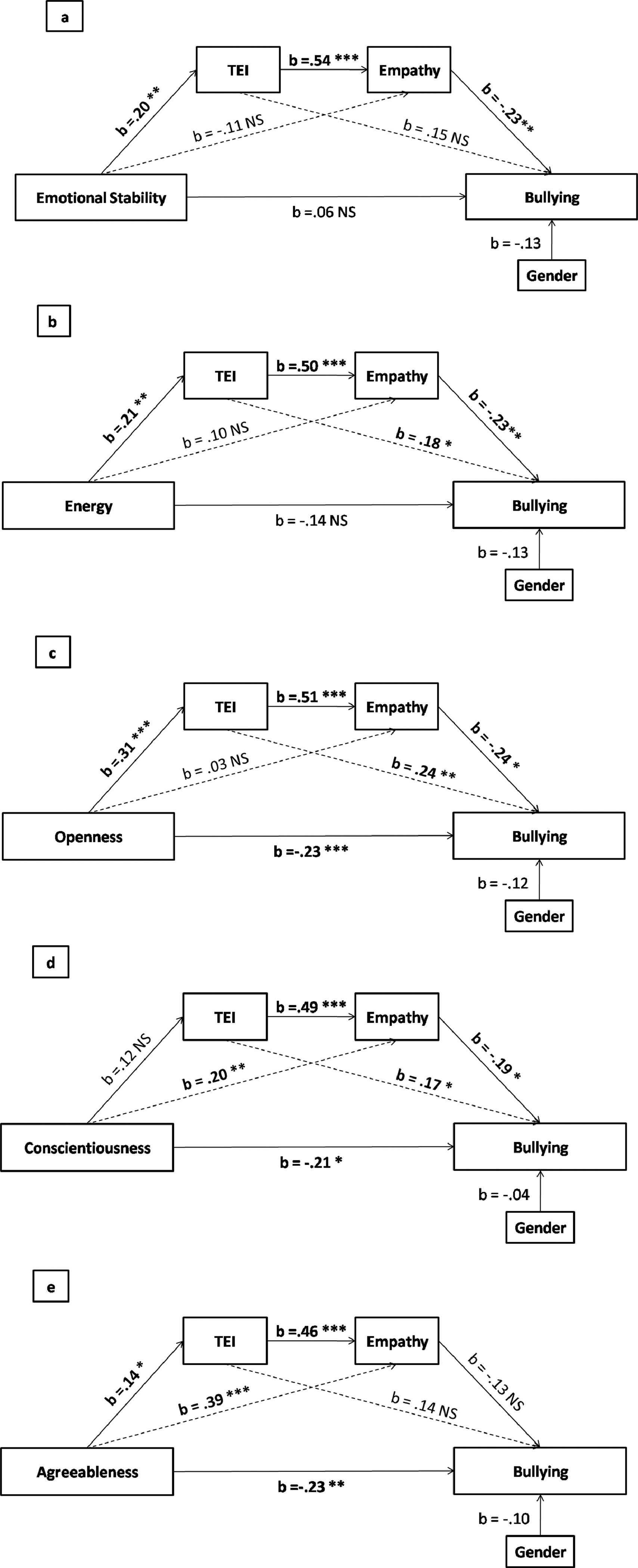

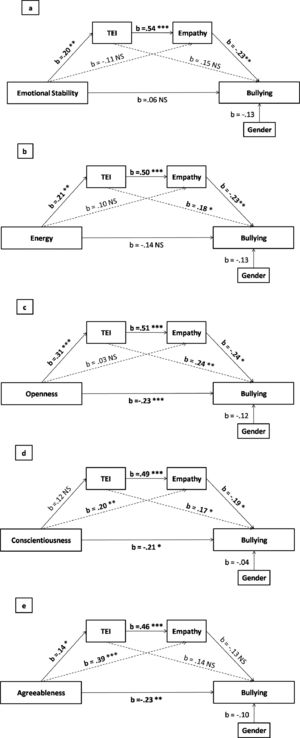

In order to investigate the hypotheses that the association between TEI and empathy mediates the association between the Big Five factors and bullying, the PROCESS macro for SPSS (version 3.5; Hayes, 2017) was used. Five sequential mediation models were run (see Fig. 1), one for each personality factor as independent variable (x), TEI and empathy as the two mediators (M1 and M2), with TEI associated to empathy, and bullying as the dependent variable (y). Gender was entered in the models as covariate. 5000 bootstrap samples were used. Bootstrapping is a non-parametric method which bypasses the issue of non-normality distribution, allowing to test the indirect effect (Bollen& Stine, 1990), even in small samples (Preacher & Hayes, 2008).

a) Sequential mediation model using the personality trait ‘emotional instability’ as the focal predictor; b) Sequential mediation model using the personality trait ‘energy’ as the focal predictor; c) Sequential mediation model using the personality trait ‘openness’ as the focal predictor; d) Sequential mediation model using the personality trait ‘conscientiousness’ as the focal predictor; e) Sequential mediation model using the personality trait ‘agreeableness’ as the focal predictor. Note. *=p<.05; **=p<.01; ***=p<.001.

As regards the first model, the direct effect of emotional instability on bullying was not significant (b = .06, p = .37). However, emotional instability was positively associated with TEI (b = .20, p < .01), which was positively associated with empathy (b = .54, p < .0001), which in turn negatively predicted bullying (b = -.23, p < .01). TEI (indirect effect = .0301, 95% BootLLCI = -.0052 - BootULCI = .0774) and empathy (indirect effect = .0266, 95% BootLLCI = -.0022 - BootULCI = .0742) did not mediate the emotional instability-bullying link separately, whereas the causal chain of TEI-empathy fully negatively mediated the emotional instability-bullying link (indirect effect = -.0249, 95% BootLLCI = -.0545 - BootULCI = -.0038). The covariate gender did not affect bullying (b = -.12, p = .33) (see Fig. 1a).

As regards the second model, the direct effect of energy on bullying was not significant (b = -.14, p = .080). Energy was positively associated with TEI (b =.21, p < .05), which was positively associated with empathy (b = .50, p < .001), which in turn negatively predicted bullying (b = -.23, p < .01). TEI (indirect effect = .0382, 95% BootLLCI = -.0051 - BootULCI = .1149) and empathy (indirect effect = -.0227, 95% BootLLCI = -.0700 - BootULCI = .0102) did not mediate the energy-bullying link separately; the causal chain of TEI-empathy did not mediate the energy-bullying link, either (indirect effect = -.0240, 95% BootLLCI = -.0655 - BootULCI = .0024). The covariate gender did not affect bullying (b = -.13, p = .32) (see Fig. 1b).

As regards the third model, the direct effect of openness on bullying was significant with an inverse relationship (b = -.23, p < .001). Openness was positively associated with TEI (b = .31, p < .0001), which was positively associated with empathy (b = .51, p < .0001), which in turn negatively predicted bullying (b = -.24, p < .01). TEI positively mediated (indirect effect = .0721, 95% BootLLCI = .0137 - BootULCI = .1488) whereas empathy did not mediated (indirect effect = -.0075, 95% BootLLCI = -.0473 - BootULCI = .0261) the openness-bullying link; the causal chain of TEI-empathy partially negatively mediated the openness-bullying link (indirect effect = -.0363, 95% BootLLCI = -.0720 - BootULCI = -.0075). The covariate gender did not affect bullying (b = -.12, p = .37) (see Fig. 1c).

As regards the fourth model, the direct effect of conscientiousness on bullying was inversely related and significant (b = -.21, p < .01). Conscientiousness was not associated with TEI (b = .12, p = .11), which was positively associated with empathy (b = .49, p < .0001), which in turn negatively predicted bullying (b = -.19, p < .05). TEI (indirect effect = .0202, 95% BootLLCI = -.0037 - BootULCI = .0637) did not mediate the conscientiousness-bullying link, whereas empathy (indirect effect = -.0381, 95% BootLLCI = -.0919 - BootULCI = -.0017) did. The causal chain of TEI-empathy (indirect effect = -.0115, 95% BootLLCI = -.0314 - BootULCI = .0018) did not mediate the conscientiousness-bullying link. The covariates gender did not affect bullying (b = -.04, p = .78) (see Fig. 1d).

As regards the fifth model, the direct effect of agreeableness on bullying was significant, inversely related (b = -.23, p < .01). Agreeableness was positively associated with TEI (b = .14, p < .05), which was positively associated with empathy (b = .46, p < .0001), which in turn did not predict bullying (b = -.13, p = .13). TEI (indirect effect = .0206, 95% BootLLCI = -.0065 - BootULCI = .0635), empathy (indirect effect = -.0499, 95% BootLLCI = -.1452 - BootULCI = .0379) and the causal chain of TEI-empathy (indirect effect = -.0084, 95% BootCI = -.0280 - BootULCI = .0064) did not mediate the conscientiousness-bullying link. The covariate gender did not affect bullying (b = -.10, p < .44) (see Fig. 1e).

DiscussionThe present study aimed to explore the relationships between personality traits and bullying and how TEI and empathy sequentially mediate this relationship in primary school children. Among the numerous factors related to the bullying behaviours, the influence of personality traits is unquestionable (Mitsopoulou & Giovazolias, 2015), but also social-emotional skills should be involved when trying to understand such a complex phenomenon (Espelage et al., 2015). To investigate if the direct association between FFM personality traits and perpetrated bullying was mediated by the causal chain TEI-empathy, five sequential mediation models were carried out, showing both direct relationships between single personality traits and bullying as well as highlighting the sequential mediation effect of TEI and Empathy on those associations.

Regarding the direct relationships, our models showed a significant negative association between bullying and openness (Fig. 1c), conscientiousness (Fig. 1d) and agreeableness (Fig. 1e).

Specifically, the direct negative relationship between openness and bullying suggests that individuals with higher openness to experience, characterized by cultural solid interests and creativity, have a lower risk of becoming bullies and cyberbullies (Escortell et al., 2020). Interestingly, the openness trait has been found to be positively correlated with mixed emotion, namely affective synchrony, tolerance for mixed stimuli, and tendency to experience mixed emotions (Barford & Smillie, 2016), suggesting that children with higher openness are more inclined to consider the emotional experience from different points of view, and for this reason they could be more competent in considering the emotional cue of a social sharing as well as in considering the consequence of acted behaviors (Barford & Smillie, 2016).

With respect to the trait of conscientiousness, its relationship with bullying is well grounded in the literature. Children with low conscientiousness tend to act in antisocial ways, which may elicit reprisal (Tani et al., 2003). Moreover, conscientiousness is a personality trait still encompassing abilities that can be supported and taught, namely self-confidence, self-regulation, self-discipline, and sensitivity to fairness. In this regard, socio-emotional skills, and precisely the related compound skills (i.e. meta-cognition and self-efficacy; CASEL, 2013) could play an essential role in fostering the protection deriving from this trait also in those children that exhibit a low conscientiousness.

Still in the view of the direct negative links between personality traits and bullying, we found that agreeableness is also involved as a protective factor by supporting children's cooperative and social-oriented behaviours (Costa & McCrae, 1992) and it is negatively related to antisocial personality (Tani et al., 2003). Accordingly, low agreeableness represents a critical risk factor for bullying behaviours. Indeed, supporting children's positive relationships may represent an effective way to prevent bullying phenomena (Anderson & Swiatowy, 2008).

Interestingly, the TEI-empathy causal chain totally mediated the emotional instability-bullying link, on the one hand, and partially mediated the openness-bullying link, on the other hand. Moreover, when considering the mediation effect of TEI-empathy on the link among energy, agreeableness, conscientiousness and bullying, TEI appears to be significantly associated with both energy and agreeableness, whereas empathy appear to be significantly associated with both agreeableness and conscientiousness. In this vein, although the TEI-empathy causal chain does not mediate the relationships between these personality traits and bullying, empathy alone mediates the conscientiousness-bullying link. This suggests that specific personality traits can be more closely negativlely associated to bullying, while socio-emotional competences may exert some role in the onset of individual behavioral differences.

Identifying relevant personality traits that are empirically linked to bullying would require a more comprehensive method, in understanding the individualised risk trajectories as well as designing tailored management plans. However, our results suggest that beyond the individual personality traits there is a constellation of socio-emotional components that can be trained, learned and educated in order to buffer negative dispositions possibly leading to bullying and to maladjusted behaviors. Whether emotional-related personality traits need a more oriented social skills perspective to account for bullying (Bollmer et al., 2006), fostering children' social-emotional skills becomes an essential objective in preventing maladaptive social responses such as violence and aggression (Poulou, 2014).

Consistently, an increasing number of studies demonstrated that the intervention programs can be effectively implemented to support socio-emotional skills growth, having a variety of positive outcomes including academic success and psychological wellbeing (Sánchez Puerta et al., 2016). Socio-emotional skills, in fact, should be the focus of whole-school approaches to prevent bullying, enhancing the awareness on the phenomenon, and increasing the use of empathy, emotion regulation, assertiveness, and friendships skills (Yang et al., 2019).

This study should be consider in the light of some limitations. The primary limitation to the generalization of these results is the reduced sample size. Nonetheless, our results are consistent with previous studies, confirming the link between some personality traits and bullying behaviors and the role of socio-emotional skills in preventing maladjustive developmental outcomes when specific personality traits are involved. Moreover, future research should consider the opportunity to directly measure the real competence performances in order to deepen our understanding both in terms of objective data and of personal awareness.

To conclude, this study represents an actual and complex perspective on understanding the key role of socio-emotional skills in mediating the effects of personality traits on bullying, thus suggesting possible new directions for its prevention.