The aims of this study were to explore the heterogeneity of resources, as described by the Conservation of Resources (COR) theory, in a sample of cancer and psoriatic patients and to investigate whether heterogeneity within resources explains differences in Posttraumatic Growth (PTG) level within each of these clinical samples and in a non-clinical control group.

MethodThe sample consisted of 925 participants, including 190 adults with a clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer, 355 adults with a medical diagnosis of psoriasis, and 380 non-clinical (without any chronic illnesses) adults, all of whom had suffered various adverse and traumatic events. The participants completed a COR evaluation questionnaire and a posttraumatic growth inventory.

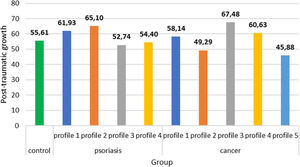

ResultsA latent profile analysis revealed four different classes of psoriatic patients and five classes of cancer patients, all with different resources levels. Clinical subsamples differed substantially with PTG levels compared to healthy controls.

ConclusionsOur study did not find a sole pattern of PTG that fit all the individuals, even for those who experienced the same type of traumatic event. Psychological counseling, in chronic illness particularly, should focus on the heterogenetic profiles of patients with different psychosocial characteristics.

El objetivo fue explorar la heterogeneidad de los recursos, según la Teoría de la Conservación de los Recursos (COR), en pacientes con cáncer y pacientes con psoriasis, e investigar si la heterogeneidad de los recursos explica las diferencias en el crecimiento postraumático (CPT) en cada una de estas muestras clínicas y en un grupo control no clínico.

MétodoLa muestra estaba formada en 925 participantes, divididos en 190 adultos con diagnóstico de cáncer gastrointestinal, 355 con diagnóstico médico de psoriasis y 380 adultos no clínicos (sin enfermedades crónicas). Todos ellos habían sufrido diversos efectos adversos y eventos traumáticos. Los participantes completaron un cuestionario de evaluación COR y un inventario de crecimiento postraumático.

ResultadosUn análisis de perfil latente reveló cuatro clases diferentes de pacientes con psoriasis y cinco de pacientes con cáncer, todos ellos con diferentes niveles de recursos. Las submuestras clínicas diferían sustancialmente con los niveles de CPT en comparación con los controles sanos.

ConclusionesNo se encontró un patrón único de CPT que se adaptara a todos los individuos, incluso en aquellos que experimentaron el mismo tipo de evento traumático. El asesoramiento psicológico, especialmente en enfermedades crónicas, debe centrarse en los perfiles heterogenéticos de pacientes con diferentes características psicosociales.

More than two decades of intensive research on Posttraumatic Growth (PTG; Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996) have brought wider attention to the paradoxical, positive consequences of traumatic events and have relevantly changed the theory and practice of studies on traumatic stress (Infurna & Jayawickreme, 2019). In addition, with the advent of positive psychology, PTG became one of its most popular research areas, which led to the construction of several theoretical models for PTG, which each differently define this term. In particular, PTG was operationalized either as an outcome of addressing a traumatic experience (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), the process of searching for meaning after trauma (Pals & McAdams, 2004), or even a compensatory illusion (Maercker & Zoellner, 2004). Despite a lack of consensus on how to operationalize PTG, most authors have observed a similar group of positive changes in individuals who have experienced adverse or traumatic life events (Jayawickreme & Blackie, 2014). These changes encompass more satisfying interpersonal relationships, finding new life possibilities, greater appreciation of life, openness to spiritual issues, and enhanced perception of personal strength (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996). While many studies on PTG exist, there are still some substantially neglected areas, one of which relates to PTG accompanied by struggling with chronic physical illness (Casellas-Grau, Ochoa, & Ruini, 2017; Purc-Stephenson, 2014).

Both the diagnosis of and living with chronic illness are associated with severe distress, which in many cases meets the criterion of a traumatic stressor (e.g., Cordova, Riba, & Spiegel, 2017; Edmondson, 2014; Rzeszutek, Oniszczenko, Schier, Biernat-Kałuża, & Gasik, 2016). However, the aforementioned distress may trigger a profound, transformative life change that reflects PTG among various patient groups (Casellas-Grau et al., 2017; Rzeszutek & Gruszczyńska, 2018). Nevertheless, illness-related trauma is different from acute traumatic life events, and this difference poses a theoretical challenge in understanding the PTG process among patients who are coping with a chronic illness (Casellas-Grau et al., 2017). More specifically, Edmondson (2014) introduced a posttraumatic stress disorder model associated with enduring somatic threat that highlighted the uniqueness of illness-related trauma, which usually begins at the moment of diagnosis and continues due to struggles with the illness, awareness of the life threat, and poor quality of life. Therefore, there is not only an association with the past (diagnosis) but an ongoing process that is linked to both the present and the future. Such traumatic experiences have been observed to a significant degree among cancer patients (see review Cordova et al., 2017) because they face a real-life threat and thus often experience cancer-related PTG (see review Casellas-Grau et al., 2017). However, the number of studies is increasing regarding PTG in individuals who are struggling with chronic, highly stressful, and debilitating but not directly life-threatening illnesses, such as arthritis (Sörensen, Rzeszutek, & Gasik, 2019), multiple sclerosis (Kim, Zemon, & Foley, 2019), and psoriasis (Fortune, Richards, Griffiths, & Main, 2005). Additionally, within research on illness-related PTG, several research gaps remain. For example, no consensus exists on the critical moment that can potentially stimulate growth in patients and how much time must pass from that moment until growth can occur (Casellas-Grau et al., 2017). Moreover, it is not known whether PTG may be experienced differently across various physical illnesses, particularly among patients who are exposed to a real-life threat versus those dealing with chronic but non-life-threatening medical conditions (Purc-Stephenson, 2014). Finally, it would be interesting to explore whether there are some discrepancies in the PTG outlook among patients who are struggling with illness-related trauma compared to non-clinical samples who are exposed to acute traumatic life events (Ramos, Leal, Marôco, & Tedeschi, 2016). In our study, we compared two groups of patients—cancer and psoriatic patients—with a non-clinical sample of adults from the general population who had experienced various adverse life events.

Receiving a diagnosis and coping with chronic illness always create multidimensional distress and difficulties in various areas of a patient's life (Llewellyn et al., 2019). A massive body of studies has shown that that this complex distress, which is present both in cancer patients (see metanalysis, e.g., Winger, Adams, & Mosher, 2016) and psoriatic patients (see metanalysis, e.g., Ali et al., 2017), significantly deteriorates well-being and treatment outcomes of patients in these groups. Therefore, our study refers to the conservation of resources theory (COR; Hobfoll, 1989) to investigate the role of subjectively assessed resources from various areas and their relationship with PTG among cancer and psoriatic patients compared to a non-clinical sample of adults from the general population. In particular, COR theory focuses not on a subjective appraisal of stress and coping (see Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) but rather on objective resources, which are operationalized as things that a person currently possesses and values (e.g., objects, states or conditions) or plans to gain in the future. Specifically, in COR theory, stress is defined as more concrete and being associated with an actual level as well as the loss or gain of resources. To date, research on the link between resources from Hobfoll's theory (1989) and PTG has been conducted predominantly on either terrorist attacks (e.g., Hobfoll, Tracy, & Galea, 2006; Littleton, Axsom, & Grills-Taquechel, 2009) or natural disasters (Cook, Aten, Moore, Hook, & Davis, 2013), whereas related studies on chronic illness are scarce (Sörensen et al., 2019). Additionally, incorporating COR resources in PTG research may be an adjunct to the ongoing dispute over how the PTG construct should be operationalized (see Hobfoll et al., 2006 vs. Tedeschi, Calhoun, & Cann, 2007).

Lastly, to the best of our knowledge, contemporary studies on PTG in general (Infurna & Jayawickreme, 2019) and on those struggling with chronic illness in particular (Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2016) have predominantly followed a variable-centered approach, which disregards the problem of the heterogeneity of participants within the studied variables. Specifically, such studies have focused on general trends for their entire study sample and neglected the possibility of the existence of profiles of participants with different psychological characteristics and their various association with PTG. Thus, the final novelty of our study is the use of the person-centered perspective.

Given the aforementioned research gaps, the aim of our study was three-fold. We firstly wanted to explore the heterogeneity of resources in the sample of cancer and psoriatic patients and investigate whether heterogeneity within resources explains the individual differences in levels of PTG within each of these patient groups while controlling for sociomedical data from the clinical samples. We then wanted to determine whether profiles of resources and PTG level differed across participants from those two clinical samples. Finally, we wanted to examine whether the observed profiles among cancer and psoriatic patients, which were extracted on the basis of their resources, differed from the healthy control group in terms of their PTG level. To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies in the PTG literature that may have been useful for us as a direct source for the research hypotheses, the study design, and the patient samples. Thus, we employed an exploratory approach. Importantly, based on some existing studies on the topic that were conducted in a different methodological framework (see Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2016), we did expect that our clinical samples of cancer and psoriatic patients would be heterogeneous in terms of resources and that participants from different profiles of resources within each of these patient groups would declare different levels of PTG; hence, we controlled for sociomedical covariates (Hypothesis 1). In addition, we hypothesized that the resource profiles and PTG levels would be different between the two clinical samples (Hypothesis 2). We also assumed that the cancer and psoriatic patients would assess their psychosocial resources, on average, at a lower level compared to the subjects from the non-clinical population (Hypothesis 3). Finally, we expected that the psoriatic and cancer patients from various profiles, which were extracted on the basis of their resources, would declare different levels of PTG compared with the healthy control group (Hypothesis 4).

MethodParticipants and procedureThe overall study sample comprised 925 participants and was divided into three groups: two clinical and one non-clinical. The first clinical group consisted of 190 adults with a clinical diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer. These patients were recruited from the Warsaw Non-Public Health Care Facility Magodent Oncological Hospital in Warsaw. The both inclusion and exclusion criteria encompassed being 18 years of age, having medically proved diagnosis of gastrointestinal cancer of at elast one year and willingness to take part of this study. Specifically, of 260 patients who were eligible for the study from that clinic, 190 were recruited and agreed to complete the questionnaires (73%), 22 declined (8%), and 48 (19%) completed the inventories yet had a high level of missing data, which precluded their inclusion in the statistical analysis.

The second clinical sample comprised 355 adults with a medical diagnosis of psoriasis. The psoriatic patients were recruited from three sources: Patients hospitalized in the Dermatology Clinic at the Military Institute of Medicine in Warsaw and the Dermatology Clinic in Provincial Hospital at Kielce, who completed paper questionnaires, and members of the Union of Associations of Patients with Psoriasis in Poland, who completed an online form via social media. Of the 180 patients who were eligible for the study in these two clinics, 105 were recruited and agreed to complete the questionnaires (58%), 36 declined (20%), and 39 (22%) completed them with a high level of missing data, which precluded their inclusion in the statistical analysis. Regarding the second mode of recruitment, 250 psoriatic patients agreed to complete the study questionnaires via social media. The online part of the study was conducted because of the desire to reach patients across Poland; we did not want to restrict the data to only clinics in large cities. This strategy enabled us to recruit patients from small towns as well as individuals without active disease at the moment and those who do not require hospitalization due to the chronic character of this illness. Importantly, to become a member of the Union of Associations of Patients with Psoriasis in Poland, the patient must submit a medically confirmed diagnosis of psoriasis. For both types of participants, the inclusion criteria included being 18 years of age or older and having had a medical diagnosis of psoriasis for at least 1 year and willingness to take part in this study. The exclusion criteria included a recent outbreak of psoriasis (i.e., less than one year).

Finally, the non-clinical sample consisted of 380 healthy adults (without any chronic illnesses), which we collected from a non-clinical population among students from various Warsaw universities with potentially similar demographic characteristics to those of our clinical samples. The control group completed the online form via social media. The both inclusion and exclusion criteria encompassed being 18 years of age or older, no history of chronic medial illness and willingness to take part of this study.

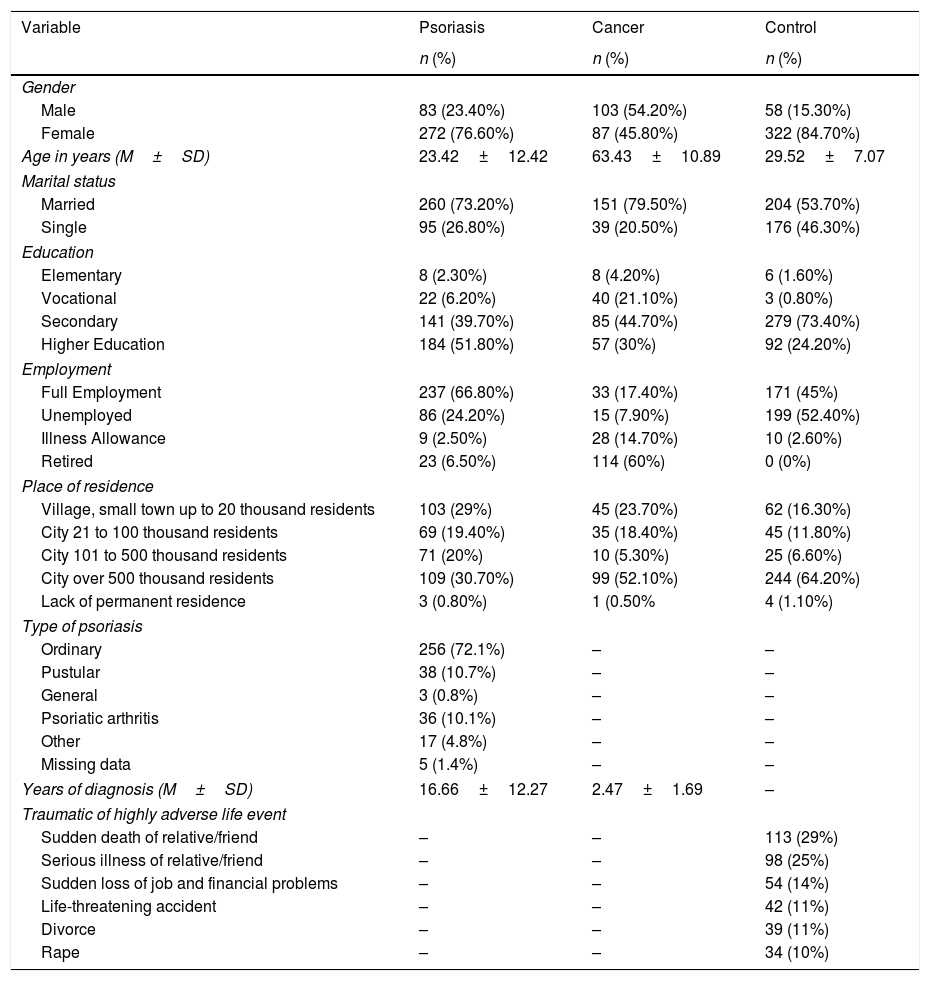

In all three groups, the participants were given informed consent forms, and they participated in the study voluntarily; there was no remuneration for participation. The research protocol for this study was approved by the local ethics commission. Table 1 summarizes the sociodemographic and medical variables in all three participant groups.

Socio-medical variables in the studied samples (N=925).

| Variable | Psoriasis | Cancer | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Gender | |||

| Male | 83 (23.40%) | 103 (54.20%) | 58 (15.30%) |

| Female | 272 (76.60%) | 87 (45.80%) | 322 (84.70%) |

| Age in years (M±SD) | 23.42±12.42 | 63.43±10.89 | 29.52±7.07 |

| Marital status | |||

| Married | 260 (73.20%) | 151 (79.50%) | 204 (53.70%) |

| Single | 95 (26.80%) | 39 (20.50%) | 176 (46.30%) |

| Education | |||

| Elementary | 8 (2.30%) | 8 (4.20%) | 6 (1.60%) |

| Vocational | 22 (6.20%) | 40 (21.10%) | 3 (0.80%) |

| Secondary | 141 (39.70%) | 85 (44.70%) | 279 (73.40%) |

| Higher Education | 184 (51.80%) | 57 (30%) | 92 (24.20%) |

| Employment | |||

| Full Employment | 237 (66.80%) | 33 (17.40%) | 171 (45%) |

| Unemployed | 86 (24.20%) | 15 (7.90%) | 199 (52.40%) |

| Illness Allowance | 9 (2.50%) | 28 (14.70%) | 10 (2.60%) |

| Retired | 23 (6.50%) | 114 (60%) | 0 (0%) |

| Place of residence | |||

| Village, small town up to 20 thousand residents | 103 (29%) | 45 (23.70%) | 62 (16.30%) |

| City 21 to 100 thousand residents | 69 (19.40%) | 35 (18.40%) | 45 (11.80%) |

| City 101 to 500 thousand residents | 71 (20%) | 10 (5.30%) | 25 (6.60%) |

| City over 500 thousand residents | 109 (30.70%) | 99 (52.10%) | 244 (64.20%) |

| Lack of permanent residence | 3 (0.80%) | 1 (0.50% | 4 (1.10%) |

| Type of psoriasis | |||

| Ordinary | 256 (72.1%) | – | – |

| Pustular | 38 (10.7%) | – | – |

| General | 3 (0.8%) | – | – |

| Psoriatic arthritis | 36 (10.1%) | – | – |

| Other | 17 (4.8%) | – | – |

| Missing data | 5 (1.4%) | – | – |

| Years of diagnosis (M±SD) | 16.66±12.27 | 2.47±1.69 | – |

| Traumatic of highly adverse life event | |||

| Sudden death of relative/friend | – | – | 113 (29%) |

| Serious illness of relative/friend | – | – | 98 (25%) |

| Sudden loss of job and financial problems | – | – | 54 (14%) |

| Life-threatening accident | – | – | 42 (11%) |

| Divorce | – | – | 39 (11%) |

| Rape | – | – | 34 (10%) |

Note: M=Mean, SD=Standard Deviation.

The PTG level was assessed with the Polish adaptation of Tedeschi and Calhoun's (1996) Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI), which includes four PTG domains: Changes in self-perception, Changes in relationships with others, Greater appreciation of life, and Spiritual changes. The original PTGI includes five PTG domains: Relating to others, New possibilities, Personal strength, Spiritual change, and Appreciation of life. In the PTGI that we used, the participants rated two statements that evaluated various changes after traumatic or highly stressful life events, which were mentioned at the beginning of the questionnaire. The participants from the clinical groups were instructed to focus on their diagnosis and how they deal with their illness in their daily lives as an example of a challenging event that could be associated with potential positive changes and thus reflect PTG. We analyzed (see data analysis) the global PTG score (sum all of items) because, due to the high intercorrelation of particular PTGI subscales, we followed the recommendations of the unifactorial assessment of PTG (Helgeson, Reynolds, & Tomich, 2006). The Cronbach's alpha coefficients were equal to .95, both in the clinical sample and in the healthy control group.

To assess the level of resources, we used a Polish adaptation of the COR Evaluation Questionnaire (COR-E; Hobfoll, 1998) in which the participants rated the extent to which they possessed resources from various areas, such as hedonistic and vital resources, spiritual resources, family resources, economic and political resources, and power and prestige resources. In the clinical sample, the subjects were also instructed to focus on the level of resources in the context of their illness experiences. The Cronbach's alpha coefficients for the COR-E varied between .77 to .89 in the clinical sample and .75 to .86 in the healthy control group.

Data analysisThe data analysis consisted of three consecutive steps: examining the associations between the sociomedical data and the dependent variable (i.e., PTG); extracting classes of respondents from the group of patients who were diagnosed with psoriasis and patients diagnosed with cancer who differed regarding the profile of their resources with the use of latent profile analysis (LPA) (Vermunt & Magidson, 2016); and examining the differences between the extracted classes and the control group in terms of PTG.

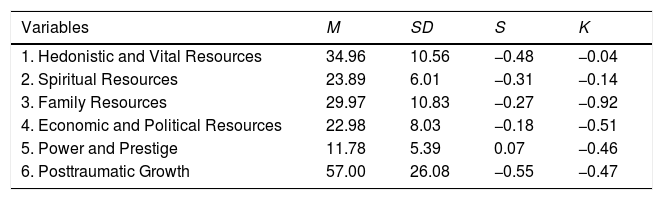

ResultsTable 2 presents descriptive statistics for the analyzed variables (i.e., mean values, standard deviations, skewness, and kurtosis measures). None of the measures of skewness or kurtosis exceeded the value of 1 or −1; therefore, we assumed a normal distribution of the analyzed variables.

Descriptive statistics for analyzed variables.

| Variables | M | SD | S | K |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Hedonistic and Vital Resources | 34.96 | 10.56 | −0.48 | −0.04 |

| 2. Spiritual Resources | 23.89 | 6.01 | −0.31 | −0.14 |

| 3. Family Resources | 29.97 | 10.83 | −0.27 | −0.92 |

| 4. Economic and Political Resources | 22.98 | 8.03 | −0.18 | −0.51 |

| 5. Power and Prestige | 11.78 | 5.39 | 0.07 | −0.46 |

| 6. Posttraumatic Growth | 57.00 | 26.08 | −0.55 | −0.47 |

Note.M: mean value; SD: standard deviation; S: skewness; K: Kurtosis.

Associations between the sociomedical data and PTG were examined via an independent samples t-test and Pearson's correlation coefficient. There was no statistical difference between men and women (t923=−0.13, p>.05). PTG correlated positively with the participant's age (r=.11, p<.01). There was no statistical difference between the group of married participants compared to the singles (t923=1.51, p>.05), and we found no statistical difference between the group of participants with higher education and the group of participants without higher education (t923=−0.27, p>.05). The mean value of PTG was equal to 58.76 (SD=24.49) in the fully employed group, and it was higher than the mean equal to 55.40 (SD=27.38) in the unemployed/retired group (t922.69=−1.97, p<.05). PTG in the group of participants living in cities with over 500,000 residents did not differ from the group that was living in minor localities (t923=−0.27, p>.05). PTG did not correlate with years of diagnosis (r=−.01, p>.05).

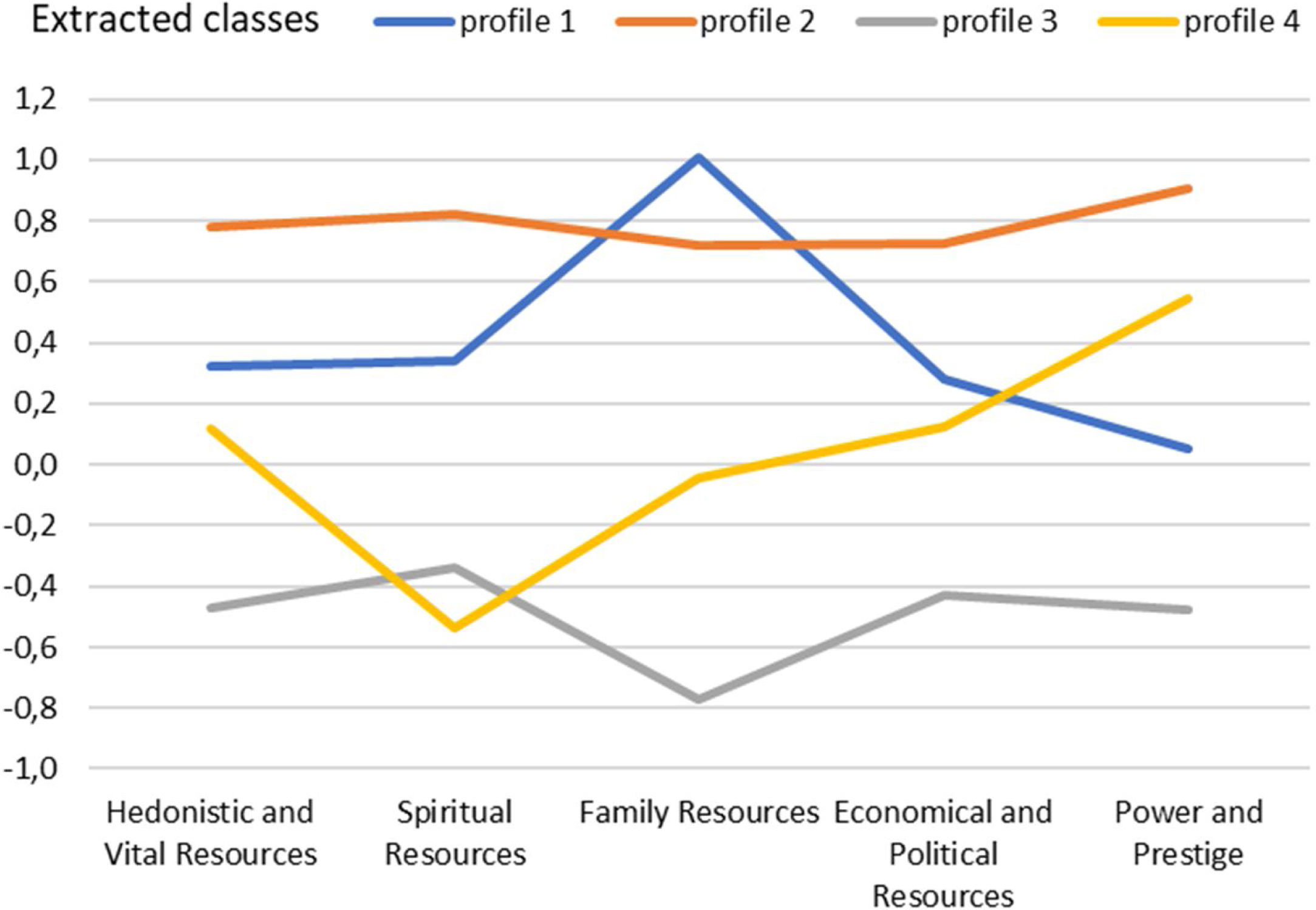

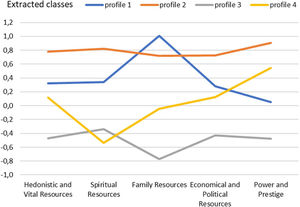

We then executed an LPA to estimate the distinct profiles and extract different subgroups of respondents who were diagnosed with psoriasis and differed in terms of resources. According to the values of the Aikake information criterion (AIC) and the Bayesian information criterion (BIC), the model with the best fit was the model with equal variances and covariances fixed to 0 and with 4 extracted classes with 4 distinctive profiles. The values of fit statistics were equal to AIC=3926.41 and BIC=4247.80 (Figure 1).

In the first class, the acquired profile was characterized by a high level of family resources (profile 1); the second class had a high level of all resources (profile 2); the third class was characterized by a low level of resources (profile 3); and the fourth class revealed a low level of spiritual resources and a higher level of power and prestige (profile 4).

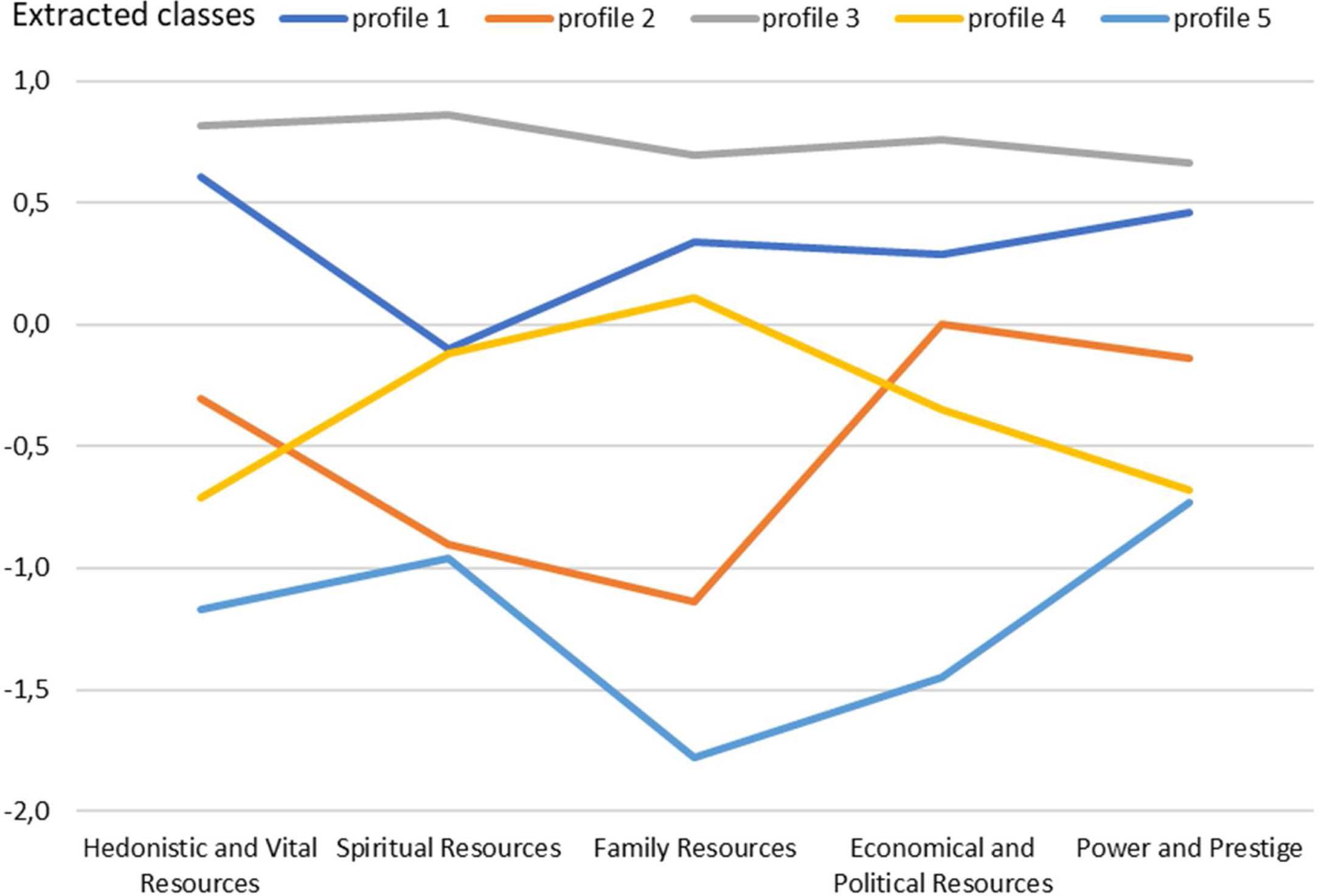

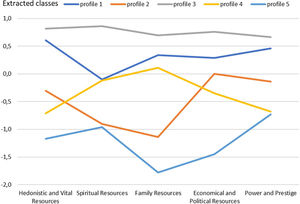

Subsequently, an LPA was executed to estimate distinct profiles and extract different subgroups of respondents who were diagnosed with cancer but differing in resources. Per the AIC and BIC values, the model with the best fit had varying variances and covariances and five extracted classes with four distinctive profiles. The values of fit statistics were equal to AIC=2100.87 and BIC=2438.56 (Figure 2).

The extracted classes were as follows: a group with high hedonic and vital resources (profile 1), a group with low spiritual and family resources (profile 2), a group with a high level of all types of resources (profile 3), a group with low vital resources and low power and prestige resources (profile 4), and a group with a low level of all types resources (profile 5).

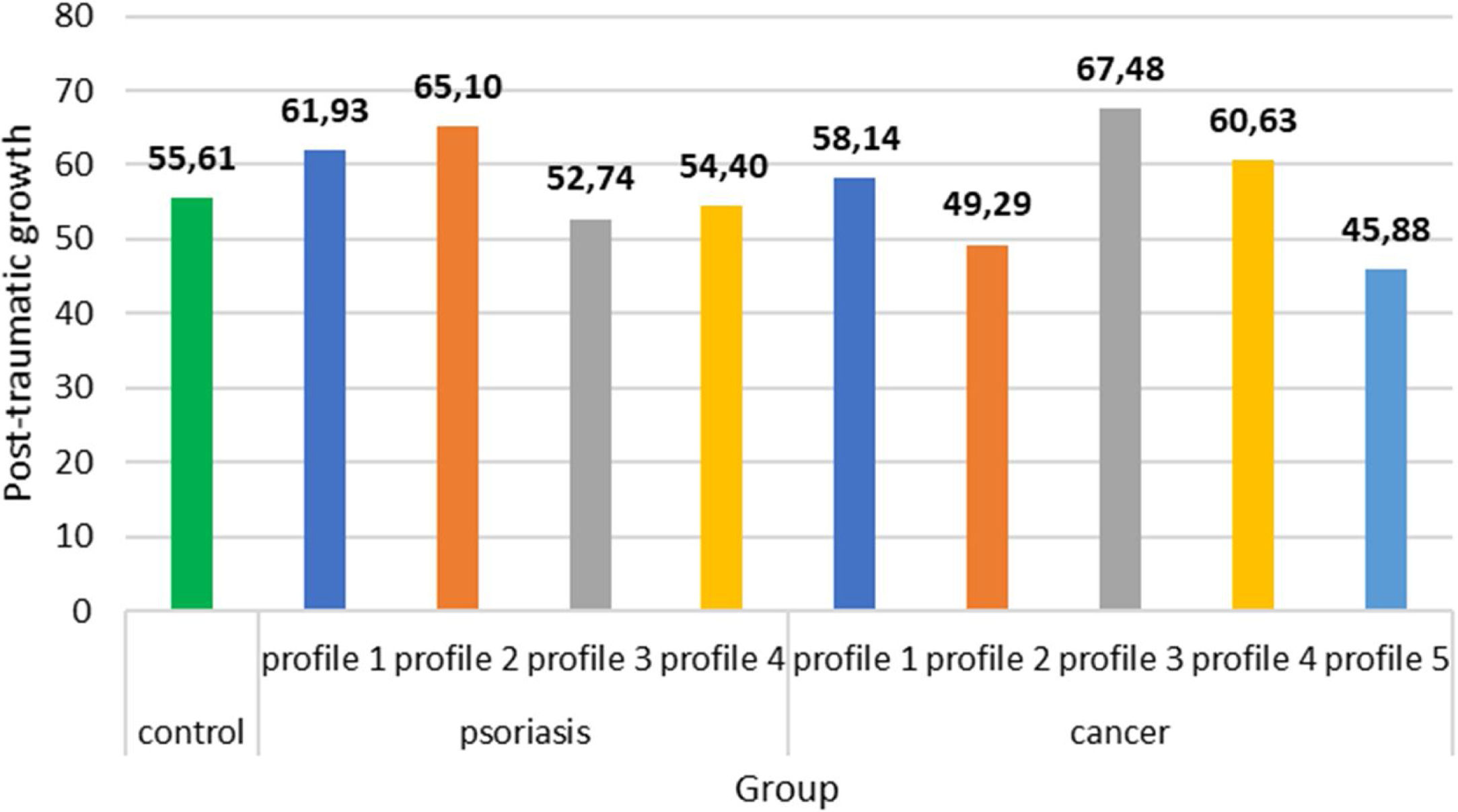

The extracted classes were compared to one another and to the control group. An analysis of covariance was performed by considering the sociomedical data that correlated with PTG. The participants’ ages and employment were included in the statistical model as covariates. The between-group differences were statistically significant (F9, 915=3.44, p<.001, η2=.03) (Figure 3).

Per the Gabriel post hoc test, the level of PTG in the third class of psoriatic patients was lower than in classes 1 (p<.05) and 2 (p<.01). The level of PTG in the third class of cancer patients was higher than in the fifth class (p<.05). PTG in the third class of cancer patients was higher than in the third class of psoriatic patients (p<.01). The second class of psoriatic patients was characterized with a higher level of PTG than was the control group (p<.05). Similarly, the third class of patients with cancer was characterized with a higher level of PTG than was the control group (p<.05).

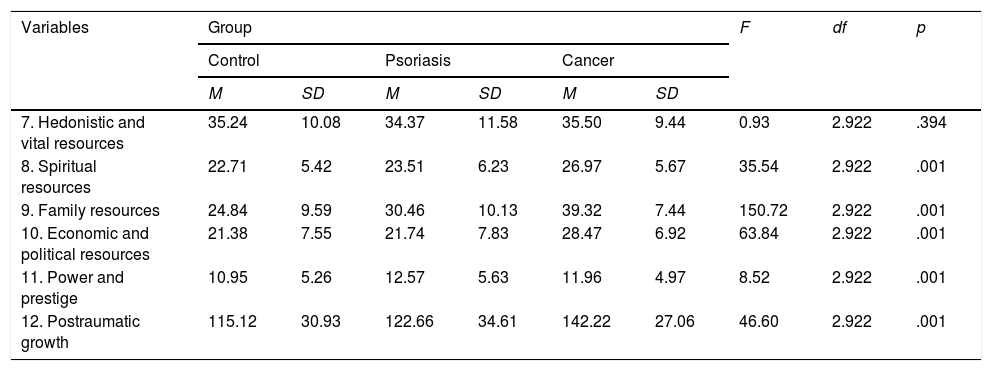

Table 3 presents the mean values of resources in the psoriatic group, the cancer group, and the control group with the values of analysis of variance.

Mean values of resources in the group of psoriatic patients, in the group of patients diagnosed with cancer and in the control group.

| Variables | Group | F | df | p | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | Psoriasis | Cancer | |||||||

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ||||

| 7. Hedonistic and vital resources | 35.24 | 10.08 | 34.37 | 11.58 | 35.50 | 9.44 | 0.93 | 2.922 | .394 |

| 8. Spiritual resources | 22.71 | 5.42 | 23.51 | 6.23 | 26.97 | 5.67 | 35.54 | 2.922 | .001 |

| 9. Family resources | 24.84 | 9.59 | 30.46 | 10.13 | 39.32 | 7.44 | 150.72 | 2.922 | .001 |

| 10. Economic and political resources | 21.38 | 7.55 | 21.74 | 7.83 | 28.47 | 6.92 | 63.84 | 2.922 | .001 |

| 11. Power and prestige | 10.95 | 5.26 | 12.57 | 5.63 | 11.96 | 4.97 | 8.52 | 2.922 | .001 |

| 12. Postraumatic growth | 115.12 | 30.93 | 122.66 | 34.61 | 142.22 | 27.06 | 46.60 | 2.922 | .001 |

Note.M: mean value; SD: standard deviation; F: analysis of variance test; df: degrees of freedom.

There were no statistically significant between-group differences regarding hedonistic and vital resources. Per the Gabriel post hoc test, the level of spiritual resources was significantly higher in the cancer patients than it was in the psoriatic patients (p<.001) and in the control group (p<.001). Similarly, the level of economic and political resources was significantly higher for the cancer patients than it was for the psoriatic patients (p<.001) and the control group (p<.001). The level of family resources for the cancer patients was higher than it was for the psoriatic patients (p<.001) and the control group (p<.001). Additionally, the level of family resources for the psoriatic patients was significantly higher than it was for the control group (p<.001). The level of power and prestige was significantly higher for the psoriatic patients than it was for the control group (p<.001).

DiscussionOur study results were consistent with the first research hypothesis, as we observed several profiles of participants from clinical samples with various levels and types of resources, and these were differently related to PTG intensity among the participants from that group. More specifically, in cancer patients, we found five profiles: a group with high hedonic and vital resources (profile 1), a group with low spiritual and family resources (profile 2), a group with high resources of all types (profile 3), a group with low vital resources and low power and prestige resources (profile 4), and a group with low resources of all types (profile 5). The PTG level was much higher in the third profile compared to the fifth profile. Four profiles were drawn for the psoriatic patients: a group with high family resources (profile 1), a group with high resources of all types (profile 2), a group with low resources of all types (profile 3), and a group with low spiritual resources and increased power and prestige resources (profile 4). PTG was significantly lower among psoriatic patients from the third profile in comparison to patients belonging to the first and second profiles. Our findings highlight the important role of resources when struggling with cancer (Winger et al., 2016) and psoriasis (Ali et al., 2017) and the psychological distress, along with the physical symptoms, which may be associated with depletion in the subjective assessed resources from various areas. Our primary explorative results can be interesting for PTG studies in general because they emphasize the significance of sample heterogeneity, which may cause the reevaluation of many inconclusive results in PTG studies (Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2016). In addition, it seems that even patients representing the same clinical entity can experience PTG much differently, which is nearly disregarded in the literature to date (Hamama-Raz, Pat-Horenczyk, Roziner, Perry, & Stemmer, 2019). Importantly, we did not find any significant relationship between PTG and the studied medical variables since the diagnosis date in either cancer or psoriasis. This finding can be discussed regarding the changing nature of many diseases, from those that are terminal to those that are chronic in character (cancer), and its relationship to the diminishing role of medical variables as predictors of well-being in chronic illness at the expense of psychosocial factors (Hernandez, Bassett, & Boughton, 2017).

Our second hypothesis was reflected in our findings only up to a point - the resource profiles and the PTG level were not much different between participants from the two clinical samples. The only significant difference was higher PTG among cancer patients from the profile with the highest of all types of resources compared to psoriatic patients from the profile with the lowest of all types of resources. This quite intuitive finding highlights the role of resources in PTG that accompany chronic illness, which remains an understudied topic (Sörensen et al., 2019). However, an essentially null result in this regard is also intriguing because, per Tedeschi and Callhoun's (1996) model of PTG, the more challenging the traumatic event is, the higher the level of PTG that should accompany it. The abovementioned trend was visible in studies on PTG among patients struggling with illness. For example, a metanalysis conducted by Sawyer, Ayers, & Field (2010) pointed to a very high level of PTG among cancer patients, most of whom face a real-life threat, painful treatment, and a profound drop in their psychosocial functioning. In line with this reasoning, we considered that our participants with cancer would have different levels of PTG compared with participants who were struggling with a hugely psychologically taxing yet chronic and non-life-threatening illness, such as psoriasis. However, our results found no discrepancies in PTG among patients representing these different medical conditions.

Surprisingly, our third hypothesis was not confirmed: both cancer and psoriatic patients assessed their resources better compared to the subjects from the non-clinical population. Specifically, the cancer patients rated their resources (spiritual, family, economic, and political resources as well as the total level of resources) as more positive than did the psoriatic patients; the poorest evaluation of resources was found in the non-clinical sample. This counterintuitive result is especially interesting because it counters the traditional trend pointing toward poor psychosocial well-being among chronically ill patients compared to the general population (Diener et al., 2016). It is notable that the role of resources from COR theory has been examined in few studies in medical settings to date (e.g., Dirik & Karanci, 2010; Sörensen et al., 2019); therefore, this variable should be investigated more thoroughly in the future.

The abovementioned postulate seems even more reasonable when we analyze the results concerning the last research hypothesis. Namely, psoriatic and cancer patients differed from the non-clinical group in PTG level, but only when we considered the differences in resource profiles. Specifically, the cancer patients from the third profile, who were high in all types of resources, declared a higher PTG than did the control group, but patients with cancer from the other profiles did not differ in PTG intensity compared to the non-clinical sample. Likewise, the psoriatic patients from the second profile, who were high in all types of resources, also had a higher PTG than did the control group, but the other profiles of psoriatic patients did not differ within that positive phenomenon from the healthy controls. One study on cancer patients did note a higher PTG level when compared to a non-clinical sample (Ramos et al., 2016), but this study was conducted in a variable-centered framework (i.e., it disregarded the existence of various subgroups of patients with different psychosocial characteristics and thus had various levels of growth). In summary, it seems that, among patients with a chronic illness, the PTG is higher compared to individuals who have experienced acute traumatic life events, but only when the perceived resources level is high.

There are several strengths to our research, including the use of a hypothesis-driven approach and applying the person-centered perspective to large samples of cancer and psoriatic patients and making comparisons to a large healthy control group. However, some limitations should also be underscored. The cross-sectional design of this study precludes causal interpretations of the observed results, especially the analysis of the process of loss or gain of resources in time. In addition, our clinical samples were heterogonous regarding medical variables. Our clinical samples concentrated only on the diagnosis and struggle with the disease as a potential PTG trigger, and we did not control for other possible traumatic events among these patient groups. In addition, it should be underscored the large age discrepancies between studied samples, i.e. patients with cancer were much older than patients with psoriasis and those from the control group, which could be related to the pattern of findings observed in our study, especially in light of the fact that age is correlated with PTG (Helgeson et al., 2006). Finally, several review studies on PTG in medical settings have underscored that the PTGI was created as an operationalization of positive changes after broad categories of traumatic events. Thus, it may not sufficiently capture the uniqueness of illness-related trauma (Casellas-Grau et al., 2017).

Despite the abovementioned limitations, our research addressed several theoretical and clinical research gaps in the PTG literature. The person-centered design provides insight above that which can be reached using variable-centered framework. For example, it is notable that there is no one pattern of PTG that correlates to what all individuals experience from the same type of traumatic event, especially patients who are struggling with illness-related trauma (Hamama-Raz et al., 2019; Pat-Horenczyk et al., 2016). From the more general perspective, the results obtained by us may be useful in clinical work with chronically ill patients (Bellver-Pérez, Peris-Juan, & Santaballa-Beltrán, 2019; Finck, Barradas, Zenger, & Hinz, 2018; Kuba et al., 2019). Particularly, psychological counseling for patients with chronic diseases, including PTG interventions (Cafaro, Iani, Costantini, & Di Leo, 2016) should focus more on the specific heterogenetic needs and profiles of patients, even those belonging to the same clinical entity.

FundingThis work was supported by the Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, from the funds awarded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the form of a subsidy for the maintenance and development of research potential in 2020 (501-D125-01-1250000, number 5011000220) and the internal funds of the University of Economics and Human Sciences and the internal funds of the Jan Kochanowski University under the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education called “Regional Initiative of Excellence” in the years 2019–2022, project no. 024/RID/2018/19.

This work was supported by the Faculty of Psychology, University of Warsaw, from the funds awarded by the Ministry of Science and Higher Education in the form of a subsidy for the maintenance and development of research potential in 2020 (501-D125-01-1250000, number 5011000220) and the internal funds of the Jan Kochanowski University under the program of the Minister of Science and Higher Education called "Regional Initiative of Excellence" in the years 2019-2022, project no. 024/RID/2018/19 and the internal funds of the University of Economics and Human Sciences.