Edited by: Dr. Sergi Bermúdez i Badia

(University of Madeira, Funchal, , Portugal)

Dr. Alice Chirico

(No Organisation - Home based - 0595549)

Dr. Andrea Gaggioli

(Catholic University of the Sacred Heart, Milano,Italy)

Prof. Dr. Ana Lúcia Faria

(University of Madeira, Funchal, Portugal)

Last update: December 2025

More infoAlthough the effectiveness of compassion-based interventions (CBIs) has been widely demonstrated to improve mental health and prosocial behaviors, not all individuals benefit equally from these interventions. Therefore, enhancing specific capacities relevant to compassion practice (i.e., mental imagery and somatosensory perception) could optimize the benefits of CBIs. This randomized controlled trial study explores the efficacy of two tools: virtual reality (VR), to improve mental imagery skills; and a heating pad used as somatosensory priming (SP), to enhance the effectiveness of a compassion practice, as compared to a control group (compassion practice only). We assessed the impact of these tools in 92 participants, randomly assigned to one of the three groups, through self-reported, physiological, and behavioral measures on three time points (before meditation, immediately after, and two weeks after). Moreover, we investigated whether individual differences in mental imagery and interoceptive skills moderate these effects. The results show that all groups benefited from the practice, regardless of the condition. Although all groups benefited from the compassion practice, positive affect increased significantly more in the VR condition, while negative affect decreased significantly less in the SP condition, compared to the control condition. Moreover, one potential moderator was identified: mental imagery skills. Specifically, criticism towards others was significantly reduced in the VR condition but only among participants with low mental imagery skills. This study underscores the importance of enhancement tools for individuals with low mental imagery skills to maximize the benefits of compassion practice.

Over the past 30 years, research on Compassion-Based Interventions (CBIs) has revealed their numerous benefits, at both the intra-personal level, such as reducing psychopathology and enhancing well-being (Kirby et al., 2017; Kirby, 2025), and the inter-personal level, including promoting prosocial behaviors and fostering solidarity (Gilbert, 2020; Karnaze et al., 2023; Klimecki et al., 2013). Cultivating compassion is thus not only crucial for alleviating individual suffering but also for fostering cooperation and social harmony, which are essential for the survival and well-being of our species (Seppälä et al., 2017). Compassion thus plays a key role in addressing several of the major challenges outlined in the World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2030 Agenda, which calls for urgent action to promote global health and equity (WHO, 2023).

While compassion has been embedded in contemplative traditions for over two millennia (Gilbert et al., 2017; Rahula, 1997), scientific interest in this concept has emerged more recently. According to Strauss and colleagues (2016), compassion is a multifaceted concept that includes cognitive, affective, and behavioral processes. These authors identified five key components of compassion: recognizing suffering, emotional resonance with it, tolerating the suffering of others or oneself, being motivated to alleviate it, and understanding that suffering is a universal experience (Strauss et al., 2016). Although the most extensively studied flow of compassion in the occident corresponds to self-compassion (e.g., Neff, 2003, Neff, 2023), compassion also includes two other flows: compassion directed toward others, or received from others (e.g., Gilbert et al., 2011), which both has received comparatively much less attention in empirical research (Quaglia et al., 2021). CBI’s can include a variety of meditations from a constructive family of practices (Dahl et al., 2015), which are aimed at strengthening, cultivating, or nurturing cognitive and affective patterns that enhance well-being, promote healthy relationships, and foster ethical values and positive perceptions through perspective-taking and cognitive reappraisal.

Despite these strengths, not all individuals who participate in these practices experience clear benefits (Gilbert et al., 2024; Kirby et al., 2017). Personal and environmental factors, as well as a lack of sustained practice, can significantly influence the outcomes of these interventions (Barceló-Soler et al., 2023; Gilbert & Mascaro, 2017). Consequently, dropout rates as high as 59 % have been reported (Leboeuf et al., 2022), thus underscoring the need for innovative approaches to enhance both the effectiveness of and adherence to these interventions. Moreover, while most research has primarily focused on self-compassion, a significant gap remains, namely, understanding the benefits of compassion directed towards others (Quaglia et al., 2021), as well as the role of individual factors in determining the benefits of these interventions.

Compassion practice involves six essential skills: imagery, attention, feeling, sensory perception, reasoning, and behavior, with the absence of any of them potentially reducing its effectiveness (Gilbert, 2009). Of these skills, mental imagery and somatosensory perception are particularly critical for ensuring the quality of compassion practice (Navarrete et al., 2021a), influencing contemplative practice through top-down and bottom-up mechanisms, respectively (Chiesa et al., 2013). Mental imagery refers to the ability to simulate or recreate real experiences through four distinct processes: generating, maintaining, inspecting, and transforming mental images (Pearson et al., 2013). Research indicates that the act of vividly imagining can activate brain regions as if the experience were actually occurring (Wilson-Mendenhall et al., 2023). As such, imagery-based practices like compassion meditation can create sensorimotor patterns in the brain that encourage compassionate behaviors. However, imagery skills vary among individuals (Borst & Kosslyn, 2010; Pearson et al., 2013), making it more difficult for some to vividly create images during compassion practice.

To address this limitation, technology may provide a promising tool. For instance, Virtual Reality (VR; immersive computer-generated environments) (Rizzo et al., 1997) may offer a solution to this by providing virtual scenarios that facilitate the generation of more vivid and dynamic mental images to enhance compassion practice (Wilson-Mendenhall et al., 2023). So far, six studies have explored the use of VR to support compassion meditation (Ascone et al., 2020; Cebolla et al., 2019; Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021; Navarrete et al., 2021b; O’Gara et al., 2022; Vidal et al., 2025), thus demonstrating its effectiveness in increasing self-compassion (Žilinský & Halamová, 2023) and compassion toward others (Cebolla et al., 2019). Most of these studies were, however, non-controlled studies. Only a few studies that used a control group showed mixed results, demonstrating that VR was capable to improve adherence but did not significantly enhance the effectiveness of compassion practice (Cebolla et al., 2019; Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021; Navarrete et al., 2021b). Moreover, it remains unclear whether the results were due to enhanced imagery skills (Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021) or are influenced by individual differences in mental imagery skills (Cebolla et al., 2019). Additionally, although heart rate variability (HRV) has been widely used as a physiological marker of compassion and social connectedness in contemplative interventions (Di Bello et al., 2020; Kirby et al., 2017), none of these mentioned studies has used physiological data to support related changes in compassion practice. Recent research in immersive VR is increasingly incorporating continuous physiological monitoring through wearable biosensors (Guillén-Sanz et al., 2024). While wearable biosensors offer important logistical advantages, traditional ECG-based systems provide greater signal accuracy and higher temporal resolution for HRV analysis compared to wearable photoplethysmography devices (Allen, 2007; Schäfer & Vagedes, 2013). For this reason, the present study uses traditional sensors to ensure the collection of reliable physiological data. In short, while VR has shown potential to enhance compassion meditation; however, further randomized controlled studies with physiological measures are needed to clarify their benefits.

Somatosensory perception refers to bodily and physical sensations that play a crucial role in the process of compassion practice (Mok et al., 2020). Sensory experiences, such as touch (Taylor et al., 2000), are often reported by practitioners as being essential to overcoming emotional blocks and cultivating compassion (Naismith et al., 2018). Furthermore, the phenomenology of compassion practice often involves physical sensations, such as warmth and bodily feelings originating from the heart or abdomen (Mok et al., 2020; Przyrembel & Singer, 2018). Until now, efforts to activate the somatosensory component in compassion practices have predominantly focused on pharmacological methods. Research suggests that substances such as 3,4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (MDMA) and intranasal oxytocin can enhance the effectiveness of self-compassion practices (Kamboj et al., 2015; Rockliff et al., 2008). However, due to potential risks and uncertain long-term effects (Buchert et al., 2003), there is a need to investigate safer alternatives.

For instance, exploring non-pharmacological alternatives to activating the somatic component is needed. One promising approach is priming, which involves implicitly modifying the intensity, duration, or quality of emotional responses by activating mental representations in response to stimuli, thereby influencing subsequent experiences (Molden, 2014; Shalev & Bargh, 2011). Although priming has been widely used in social psychology (Bargh & Chartrand, 2000) to examine its effects on trust (Kang et al., 2011) and prosociality (Storey & Workman, 2013), only one study has tested this technique in the context of compassion meditation. Specifically, Buric and her colleagues (2024) proposed the use of somatosensory priming (SP) (with a warm pad) as a tool to potentially enhance compassion practice. While the results were promising, showing that SP significantly reduced self-criticism in participants compared to other groups, it did not demonstrate any cumulative effect when combined with compassion meditation.

In summary, although CBIs have demonstrated effectiveness, individual factors such as mental imagery skills and somatosensory perception may influence both the outcomes and adherence to the practice. This underscores the importance of testing innovative tools to optimize these interventions.

In the present study, we examined the effects of enhancing mental imagery skills and somatosensory perception within compassion practice. To do this, participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups: (1) the VR group, in which VR was integrated into a compassion practice to enhance mental imagery skills; (2) the SP group, in which SP was incorporated into the same practice to activate somatosensory perception; and (3) a control group, which performed the same compassion practice with no additional tools. Participants completed the compassion practice in the laboratory and were instructed to continue practicing at home for two weeks. Assessments were conducted before (T1) and after (T2) the laboratory session, as well as two weeks after the home practice (T3).

We hypothesized that participants in the VR and SP conditions, compared to the control group, would exhibit greater increases in positive affect, compassion toward others, HRV, well-being, prosocial behavior, practice quality, and adherence, along with greater reductions in negative affect and criticism toward others. In addition, we exploratorily examined whether individual differences in mental imagery and interoceptive skills moderated these effects. Given the exploratory nature of this analysis, no specific hypotheses were proposed.

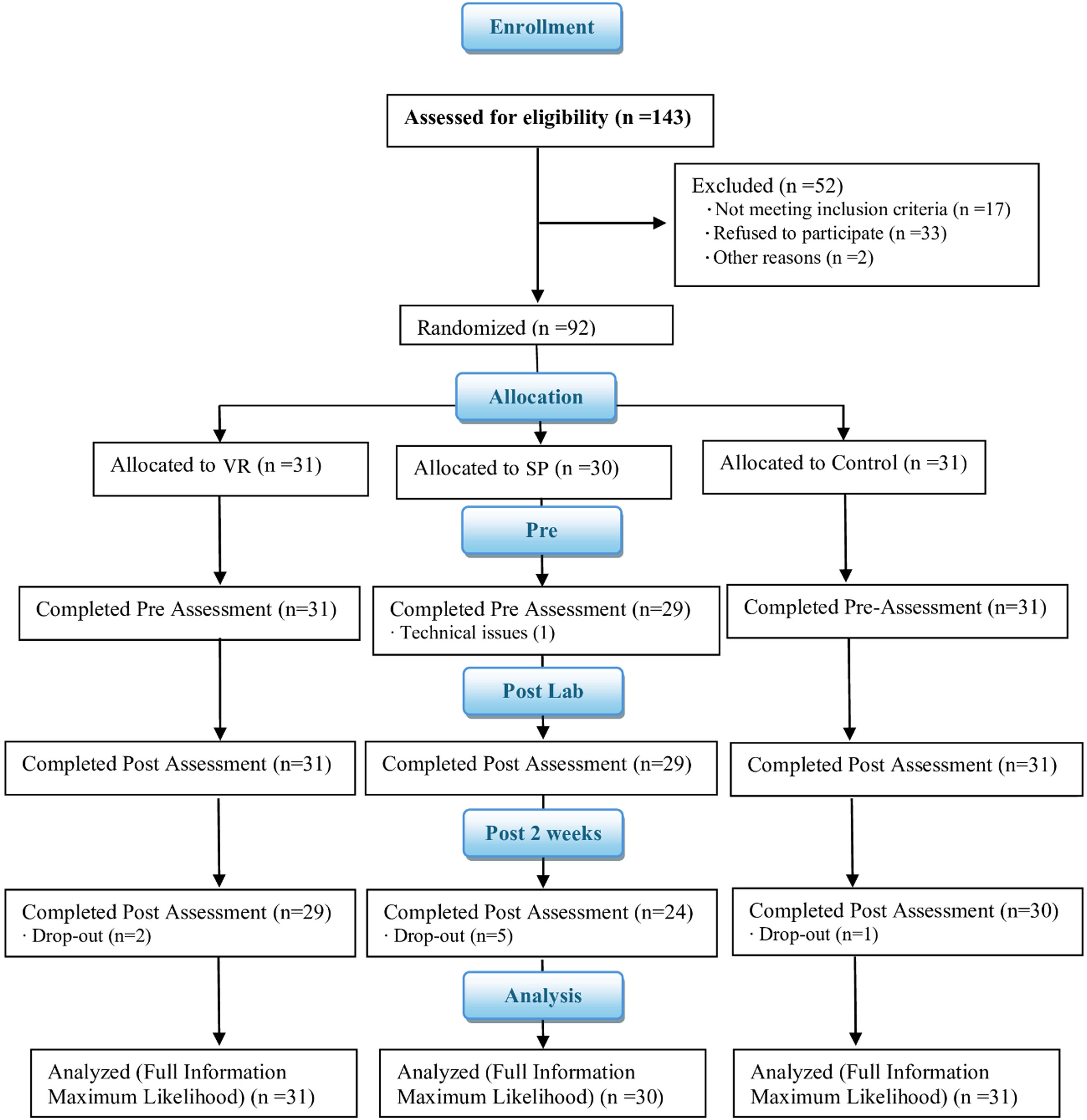

MethodsDesignThe present study employed a 3 × 2 factorial design (Montero & León, 2007), where in the two factors were: (1) condition (VR, SP, or Control) and (2) time (T1-T2 or T1-T3). The time factor referred to two distinct assessment periods: the pre-post lab session (T1-T2), conducted entirely under controlled in-lab conditions, which involved measurements taken before and immediately after the laboratory intervention, and the pre-post follow-up period (T1-T3), conducted entirely online which involved measurements taken before the lab session and again after two weeks of at-home practice (see Fig. 1).

Study design and assessment timeline.

Note: VR = Virtual Reality; SP = somatosensory Priming; C = Control; HRV = Heart Rate Variability; BETT = Betts Mental Imagery Questionnaire; ISAQ = Interoceptive Sensitivity and Attention Questionnaire; HAAS = Hedonic Affect and Arousal Scale; VAS = Visual Analogue Scale; SOCS-O = Sussex–Oxford Compassion for Others Scale; WEMWBS = Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale; PRJ = Presence and Reality Judgement in Virtual Environments; CPQS = Compassion Practice Quality Scale.

In the laboratory, participants first completed baseline measures (T1) and received a brief psychoeducation on compassion and the specific meditation used in the experiment, Tonglen meditation (TM). TM is a Tibetan Buddhist compassion practice that means ‘give and take’. It consists of a visualisation practice that invites meditators to face the suffering of others while cultivating compassion (Drolma, 2019). Before and after the TM, conscious breathing exercises are typically performed to center their attention. The most common instructions in TM practice involve several steps. Firstly, the suffering of the other (physical, mental, emotional, and situational) is visualized in the form of black smoke, which the practitioner inhales into his or her heart. The heart is represented as a jewel that transforms and extinguishes the suffering. Upon exhaling, the practitioner sends out compassionate wishes for happiness and well-being, which are represented as white light or white smoke (McKnight, 2014). After the laboratory session, participants completed the post-assessment (T2). Immediately afterwards, participants were given access to a guided 15-minute TM practice through the mobile application (M-Path; Mestdagh et al., 2023), which they were instructed to use daily as homework during the two-week follow-up period. To enhance the ecological validity of the daily meditation practice measure, participants were free to complete or not the daily homework according to their own availability and motivation. At the end of this period, they completed additional follow-up questionnaires sent through email (T3). Each condition involved a 15-minute TM practice, which was guided by the same audio narrative to ensure consistency across conditions.

VR conditionThe VR group used a VR environment designed to provide users with a strong sense of immersion and isolation within the virtual environment, allowing them to visualize the practice. The session began with participants creating avatars for themselves and the person to whom they would be sending compassion. Next, they practiced coordinating their breathing with the movements of the joystick to become familiar with the controls. Once comfortable, participants proceeded to the meditation, which was structured in three blocks. The first and last block focused on attention to breath and body, while the middle block, the TM block, involved observing the chosen person surrounded by black smoke representing their suffering. With the breath, participants inhaled the black smoke, symbolizing the suffering of the other, (see Fig. 2A) and exhaled white smoke, representing the compassionate wish for the other’s well-being (see Fig. 2B) all facilitated by the joystick. The TM-VR was developed using the Unity engine (2021.3.16f1), programmed in C#, and supported with specific XR Management and XR Interaction Toolkit plugins. Meta Quest 2 headsets were used as a visualization display, connected to the computer that allowed the research team to control the participants’ viewpoint on the computer screen. Quest 2 controllers were used to navigate in the VR environment, which allowed navigation in the start menu, avatar customization, practice training, and scrolling through a brief text-based tutorial presented before the meditation practice. The user interface was designed with Photoshop and developed with Unity. For further details, see the preliminary study using this VR environment by D’Elia et al., 2025.

SP conditionThe SP group used a soft heating pad in a form of a cushion, which was positioned on the participants’ laps prior to the meditation and remained there throughout the session. The pad featured upper pockets for the hands, allowing participants to place their hands in them if desired, although they were free to move their hands across the pad during the practice (see Fig. 3).

Control conditionFinally, participants in the control group were instructed to sit comfortably in a chair with their feet on the floor and to follow the same audio guidance as the other groups. No additional tools to enhance the practice were provided.

ParticipantsThe research was approved by the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia (registration number: 2023-MAG-2748,237), and pre-registered OSF (DOI: 10.17605/OSF.IO/3Z6TW). All activities with human participants adhered to the principles described in the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent revisions, or equivalent ethical standards. Only volunteers participated in the study. They were informed about their right to withdraw at any time and assured of the privacy of their data before signing the informed consent form. A priori power analysis with G∗Power 3.1 software (Erdfelder et al., 2009) indicated that a sample size of eighty-four participants was sufficient to achieve 90 % power for a repeated measure, within-between interaction analysis with a small effect size (0.20) and a probability of error of 0.05. The number of participants was increased by 10 % due to possible dropouts. Inclusion criteria were being over 18 years old and fluent in Spanish. Exclusion criteria were current diagnosis of a psychological disorder, or previous diagnosis of post-traumatic stress disorder, use of medications that could affect HRV measures and substance use or abuse.

The sample was recruited in the city of Valencia and surrounding areas through social media, posters, and the snowball technique. All interested participants were directed to a QR code linking to a screening survey. Once enrolled, participants were randomly assigned to one of the three conditions (VR group, SP group, or control group) using the online randomization tool available at https://www.randomizer.org/. All participants were blind to the randomization. The researcher, however, was aware of the assigned intervention in order to prepare the corresponding materials before the session. A total of 143 individuals were enrolled, of whom 92 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Of these 92, only one participant did not complete the laboratory session due to technical problems, while 83 completed the follow-up after two weeks (see Fig. 4). All participants received €50 compensation for their participation.

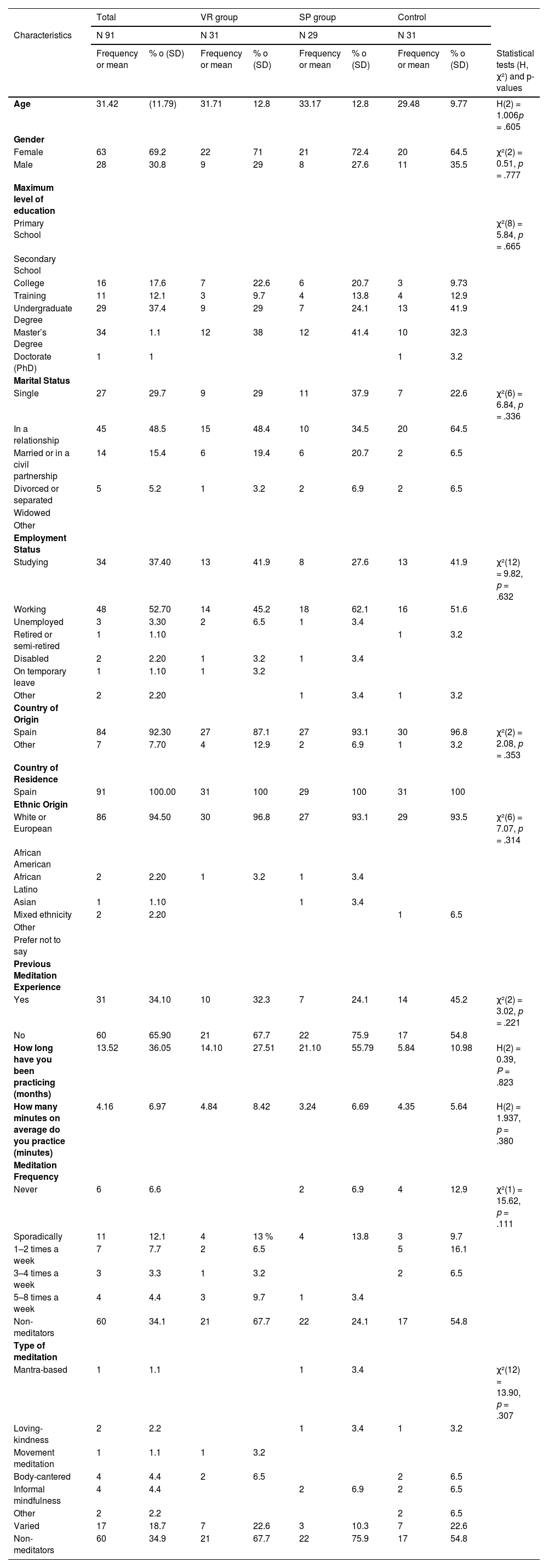

The sample had a gender distribution of 63 % female, with a mean age of 31.42 (SD = 11.79) ranging from 18 to 61 years. The educational level of the sample was predominantly higher education 70.33 % (N = 64), and more than half of the sample were actively employed (52.7 %, N = 48). All participants were residents of Spain at the time of the study and the majority were of Spanish origin (92.3 %, N = 84). Regarding meditative practice, 34.1 % (N = 31) had previous experience with meditative practices. The general characteristics of the participants are summarized in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample and differences between groups.

Note: VR= virtual reality; SP= somatosensory priming; C= control; SD= standard deviation.

Socio-demographic data were measured, including age, gender, educational level, marital status, occupation, country of residence, ethnicity, and meditation experience.

Baseline questionnaires T1/ moderatorsThe Betts Mental Imagery Questionnaire (BETT; Campos & Perez-Fabello, 2005; Sheehan, 1967) assesses the vividness of mental imagery according to eight factors: gustatory, olfactory, kinesthetic, organic, auditory, cutaneous, a heterogeneous triad (cutaneous, olfactory, and gustatory), and two types of visual imagery. It consists of 35 experiences rated on a 7-point Likert scale (1 = No image present, you only know the object you are thinking about; 7 = Perfectly clear and vivid as the actual experience). The Spanish validation shows good psychometric properties, with an overall Cronbach’s alpha of 0.92 (Campos & Perez-Fabello, 2005). In the current sample, adequate internal consistency was also observed (McDonal’s omega, ω = 0.96).

The Interoceptive Sensitivity and Attention Questionnaire (ISAQ; Bogaerts et al., 2022) consists of 17 statements designed to assess attention and sensitivity to interoceptive stimuli on a 5-point Likert scale (ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree). In our study, only the subscale measuring sensitivity to neutral body sensations was used. According to the validation, it has strong convergent, divergent and construct validity, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.80 (Bogaerts et al., 2022). It also showed adequate internal consistency (ω = 0.80) in our sample.

Pre-post questionnaires in laboratory session T1-T2The Hedonic Affect and Arousal Scale (HAAS; Roca et al., 2023) is a validated 12-item adjective list (original version in Spanish) designed to assess affect in two dimensions: valence (positive/negative) and arousal (high/low). Participants rate how well each adjective describes their current feelings on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all to 4 = extremely). The original version of this questionnaire was developed in Spanish with relatively good consistency (ω = 0.71 to 0.83) (Roca et al., 2023). In this study we found similar internal consistency (ω = 0.70 to 0.80).

An ad-hoc measurement of criticism and compassion states towards others was conducted using a Visual Analogue Scale (VAS), adapted from Falconer et al. (2015). This scale consists of an 8-item adjective list (Kind, Critical, Distant, Warm, Cold, Dismissive, Connected, Reassuring) that assesses the current state of criticism and compassion towards others. Participants rated each adjective on a 5-point Likert scale (0 = not at all, 4 = extremely) to reflect their emotional state at that moment. The original version showed good internal consistency, with Cronbach’s alpha of 0.91 for self-compassion and 0.87 for self-criticism. In our study, we found a slightly lower, but still satisfactory, level of internal consistency, with ω = 0.75 for compassion towards others and ω = 0.78 for criticism towards others.

Pre-post follow-up questionnaires at two weeks of training T1-T3The Sussex-Oxford Compassion for Others Scale (SOCS-O; Gu et al., 2020; Sansó et al., 2024) comprises 20 items rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = not at all true; 4 = always true) to measure 5 dimensions of compassion for others: recognition of the universality of suffering, recognition of suffering, empathy with those who suffer, tolerance of uncomfortable emotions, and motivation to alleviate suffering. The scale has shown a satisfactory internal consistency measured by Cronbach’s alpha ranging from 0.87 to 0.93 (Sansó et al., 2024), as did in our sample (ω = 0.90).

The Warwick-Edinburgh Mental Well-Being Scale (WEMWBS; Serrani Azcurra, 2015; Tennant et al., 2007) assesses positive aspects of mental health, including subjective well-being and psychological functioning, over the past two weeks. It consists of 14 items describing participants’ feelings rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never; 5 = all the time). The questionnaire has shown excellent internal consistency and reliability, both in its Spanish version (α = 0.89) (Serrani Azcurra, 2015) and in the present research (McDonald’s omega of 0.92).

Other measuresThe Presence and Reality Judgement in virtual environments (PRJ; Baños et al., 2000)) is an 18-item scale designed to evaluate three dimensions of a VR experience using a 10-level Likert-type scale (1 = not at all; 10 = absolutely): reality judgement (8 items), internal/external correspondence (6 items), and attention/absorption (4 items). The scale has shown good internal consistency both in the original version (α = 0.82) (Baños et al., 2000) and in our sample (ω = 0.95). This scale was administered exclusively to participants in the VR group after the laboratory session (T2).

HRV is recognized as a biomarker for compassion meditation training (Kirby et al., 2017), reflecting an individual’s sense of safety and social connectedness and providing an objective measure of compassion (Di Bello et al., 2020). In this study, HRV was measured as the root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD), a well-validated indicator of HRV (Laborde et al., 2017). Data were collected using an electrocardiogram (ECG) with the Biopac MP160 system and analyzed using iMotions v.10 software (iMotions A/S, 2022) at a 200 Hz sampling rate. Baseline HRV was measured for 5 min prior to the meditation session, followed by a 5-minute measurement during the TM practice.

The Compassion Practice Quality Scale (CPQS; Navarrete et al., 2021a), originally validated in Spanish, measures the quality of compassion practice across two dimensions: mental imagery and somatic perception. It contains 12 items rated on a scale from 0 to 100, where participants indicate the percentage of the time that each statement reflects their experience. The original version demonstrated good reliability in both subscales (Cronbach’s α = 0.91 for mental imagery and α = 0.89 for somatic perception), which was consistent with our findings (omega of 0.86 and 0.88, respectively). This scale was administered exclusively at T2 to evaluate the quality of the laboratory TM practice.

An Ad-hoc Behavioral task to measure altruism (adapted from Kwon et al., 2023) was administered at T3. In this task, participants were asked to decide what percentage of the €50 they receive for participating in the study (ranging from 0 % to 100 %) they would like to donate to various NGOs, including Médecins Sans Frontières, Greenpeace, UNICEF, and WWF. At the conclusion of the experiment, participants were informed that they would retain the full amount, though they were free to transfer their chosen donation to the specified NGOs. While this task does not explicitly assess compassion, it can serve as an approximate measure of compassion tendencies (Leiberg et al., 2011).

Adherence to daily meditation practice was assessed through a daily self-report sent through a mobile application (M-Path; Mestdagh et al., 2023). Every day at 9 pm., the participants were asked a single-item question (“Did you meditate today?”; yes/no). Adherence was quantified as the total number of days participants reported meditating during the two-week period.

Finally, adverse effects were measured using a scale adapted from Britton et al. (2021). This scale consists of three items that assess the presence, severity, and type of potential meditation-related adverse effects, covering nine different types. This scale was administered only at T3.

Data analysisFirst, normality and comparability among groups were studied. It was found that the variables of interest had a non-normal distribution with some outliers. Statistical analyses that do not require these assumptions, such as nonparametric analyses and estimation methods that correct for non-normality, were therefore used. For randomisation checks, the chi-square test (χ²) was used for categorical variables, and the Kuskal-Wallis test for continuous variables. To test the effect of TM, a Wilcoxon rank test was performed on the control, comparing pre-intervention scores (T1) to post-intervention scores (T2 and T3). All checks tests were performed with SPSS v26.0.

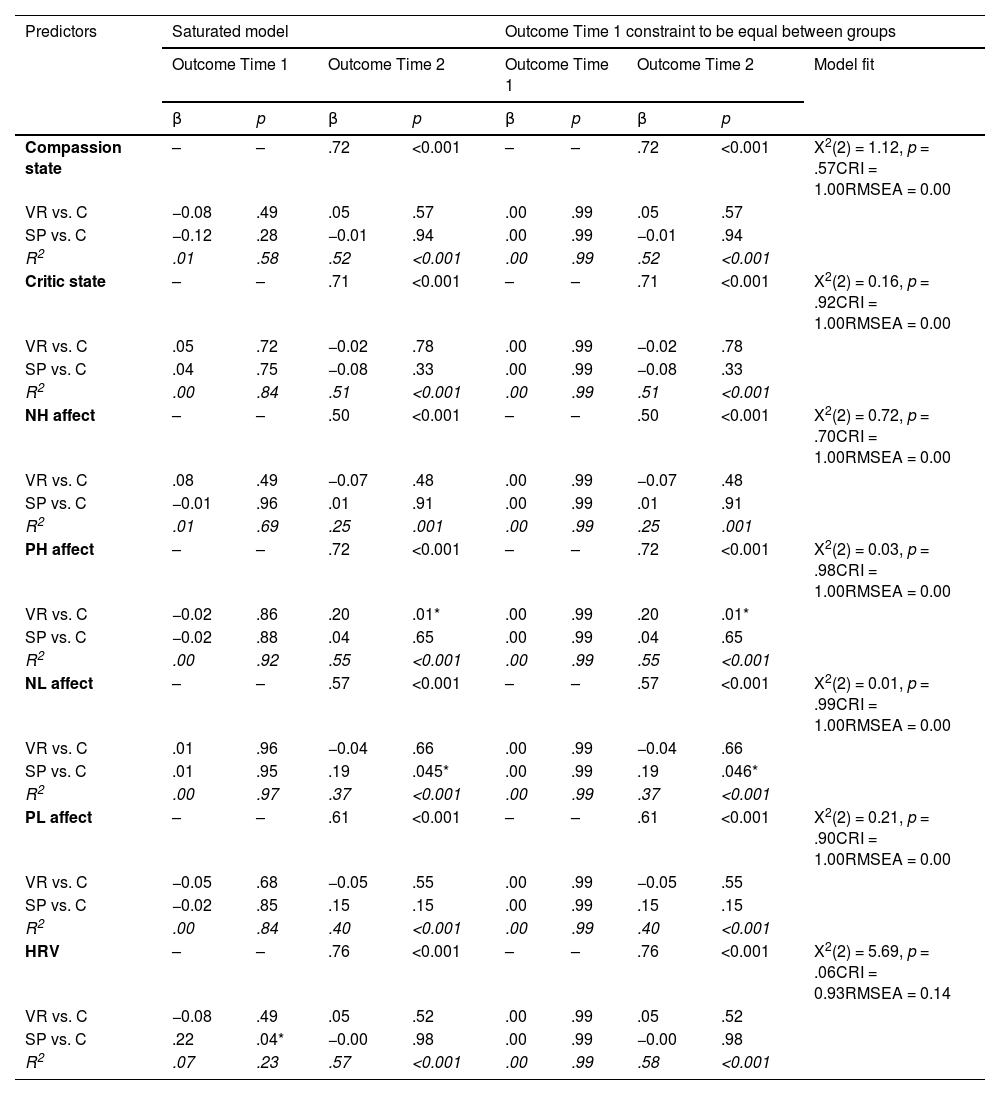

Intervention effects and moderations were tested using autoregressive models (Seppälä et al., 2020). These analyses were performed in Mplus (Version 8.1 Muthén & Muthén, 2017), using a robust estimator (Maximum Likelihood Robust, MLR) due to the presence of outliers and the non-normal nature of the distributions of the variables. Moreover, this procedure allowed us to estimate missing data from dropouts through Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML). This procedure for handling missing data has been consistently shown to outperform traditional approaches such as complete case deletion and single imputation, yielding results comparable to those obtained with multiple imputation (Enders & Bandalos, 2001; Hallgren & Witkiewitz, 2013; Lang & Little, 2018; Lee & Shi, 2021). For a detailed description of the FIML procedure, see Peugh and Enders (2004). Following Seppälä et al. (2020), FIML was used to handle missing data due to participant dropout. This approach provides unbiased parameter estimates under the missing-at-random assumption and optimizes statistical power by incorporating all available data (Little and Rubin, 2019). In autoregressive models, each post-intervention outcome (T2 or T3) is regressed on the pre-intervention outcome (T1) and dummy variables that compare each experimental group (VR or SP) with the reference group (control group). Thus, each condition was compared with the control group and not with each other (see Fig. 5). These models are saturated models with zero degrees of freedom. Consequently, fit indices cannot be computed. Since randomization theoretically guarantees the equivalence between groups at T1, the effects of the dummy variables on the outcome pre-intervention (T1) were fixed to zero (no differences between groups). These constraints offer the model degrees of freedom and fit indices can be estimated. Simultaneously, an adequate model fit supports the equivalence between groups pre-intervention. To evaluate the adequacy of the model fit several indices were considered: chi-square test, Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and the Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR); using the established cut-off criteria: CFI ≥.90, RMSEA and SRMR ≤.08 (Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2015; Marsh et al., 2004).

Moderations were introduced into the model with interaction terms. The moderator is included in the model along with two interaction terms: the product of the moderator (centered) and each dummy variable. These analyses were conducted separately for each outcome and moderation analysis.

ResultsThe randomization check showed that all variables, both demographic (Table 1) and variables of interest (Table A1, Appendix A), were equally distributed across the three groups, with the exception of HRV (H (2) = 6.709; p = .035), which showed higher levels in the VR group (Mdn = 30.13) relative to the SP (Mdn = 46.76) (U = −2.585; p = .029) (Table A2, Appendix A). However, this difference does not impact the analyses, since the comparisons are made between the interventions and the control group, rather than between the interventions themselves.

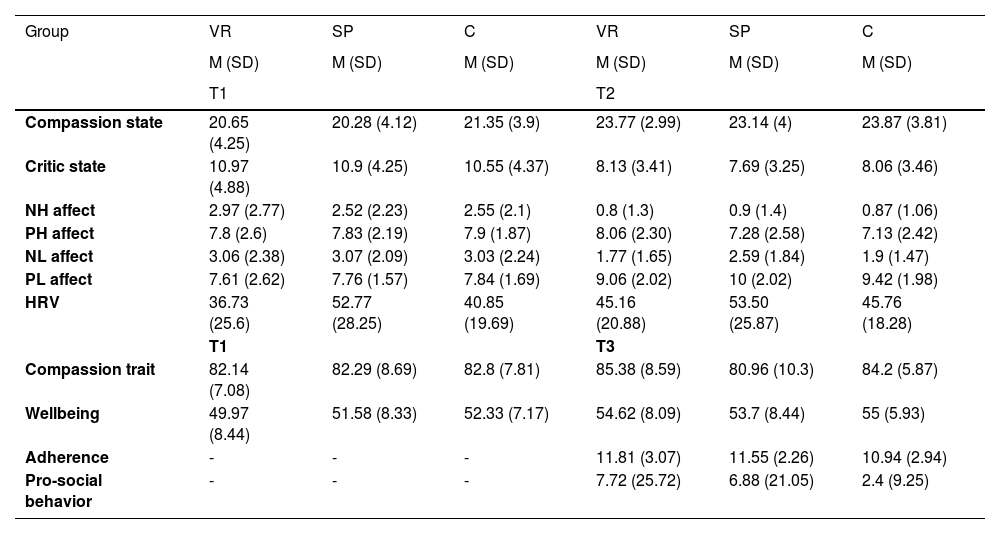

The effectiveness of TM was also confirmed. Specifically, it showed that an initial meditation session in the lab increased levels of state compassion towards others (W = 3.854; p < .001), low positive affect (W = 3.857; p < .001), and HRV (W = 1.979; p = .024), and decreased the state of criticism towards others (W = −3.811; p < .001), negative affect of both high (W = 4.158; p < .001) and low arousal (W = 3.065; p = .001), as well as high positive affect (W = −2.09; p = .010).

After two weeks’ training, participants’ well-being increased (W = 1.917; p = .028), but there was no increase in trait compassion towards others (W = 1.095; p = .137). Moreover, changes in prosocial behavior after two weeks could not be determined, as it was only assessed immediately after the laboratory session (see Table B1, Appendix B).

Moreover, the quality of the immersive environment was shown to be acceptable, with participants scoring above the midpoint on all dimensions of the presence feeling and reality judgement scale. For more details, see Appendix C.

Although 54.2 % of participants experienced some challenging moments during the meditation, which is common in compassion-based practices, only 19.3 % (N = 16) reported that these problems impacted their ability to function normally (Table D1, Appendix D). The most frequently mentioned issue was ‘Having trouble enjoying things I used to enjoy’ (Table D2, Appendix D).

Finally, there were no statistically significant differences between dropouts and completers (see Table E1, Appendix E).

Effect of exposure to different tools (VR and SP)Pre-post laboratory sessionThe results indicate that the VR group exhibited a significantly greater increase in high-arousal positive affect compared to the control group (β = 0.20; p = .01), with a small-to-moderate effect size after controlling for T1 levels. Similarly, the SP group showed a significantly smaller reduction in low-arousal negative affect compared to the control group (β = 0.19; p = .045), with the standardized beta suggesting a small effect size. Descriptive values are presented in Table 2, and the differences between groups are shown in Table 3.

Descriptive values of the variables.

Note: NH= negative high arousal affect; PH= positive high arousal affect; NL= negative low arousal affect; PL= positive low arousal affect; HRV= heart rate variability; VR= virtual reality; SP= somatosensory priming; C= control; SD= standard deviation.

Differences between groups before and after meditation T1-T2.

Note: NH= negative high arousal affect; PH= positive high arousal affect; NL= negative low arousal affect; PL= positive low arousal affect; HRV= heart rate variability; VR= virtual reality; SP= somatosensory priming; C= control; SD= standard deviation.

Note: * = p<.05.

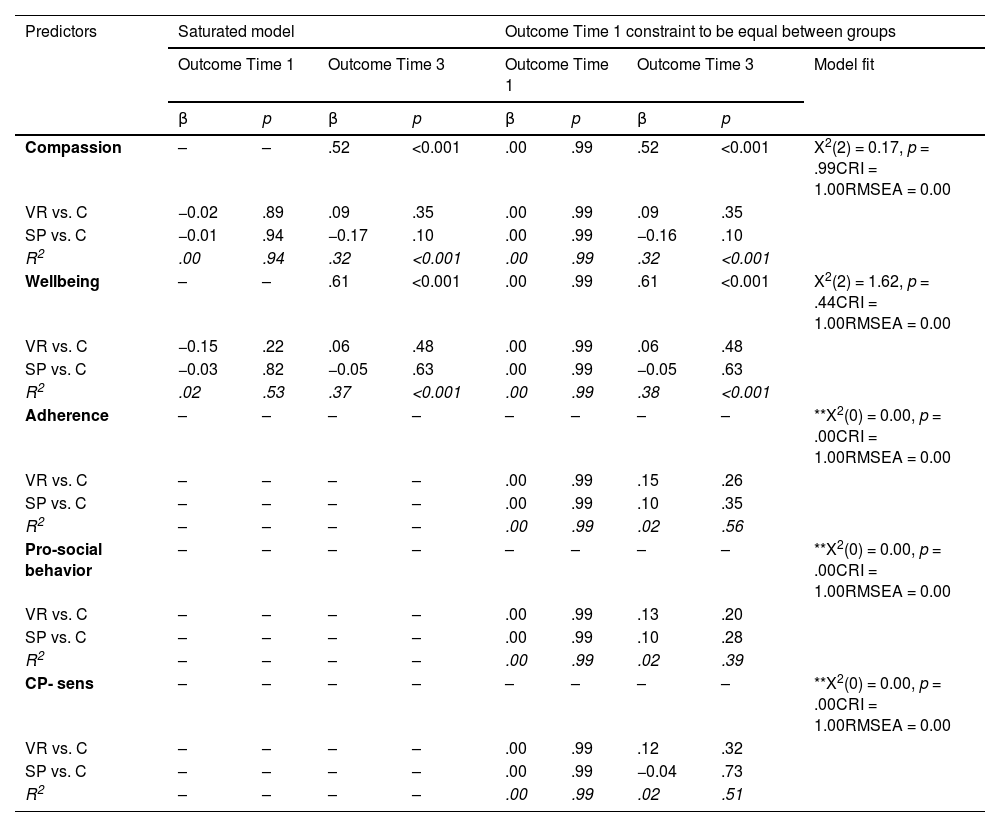

No difference was observed among the three groups after two weeks in any of the variables, as shown in Table 4.

Differences between groups before and after two weeks of meditation T1-T3 and only after meditation T3.

Note: CP-sens=, Sensorial quality of compassion practice; VR= virtual reality; SP= somatosensory priming; C= control.

**Models for Adherence, Pro-social behavior and CP-sens are saturated models without degrees of freedom because there is no pre-intervention measure of these variables.

* = p<.05.

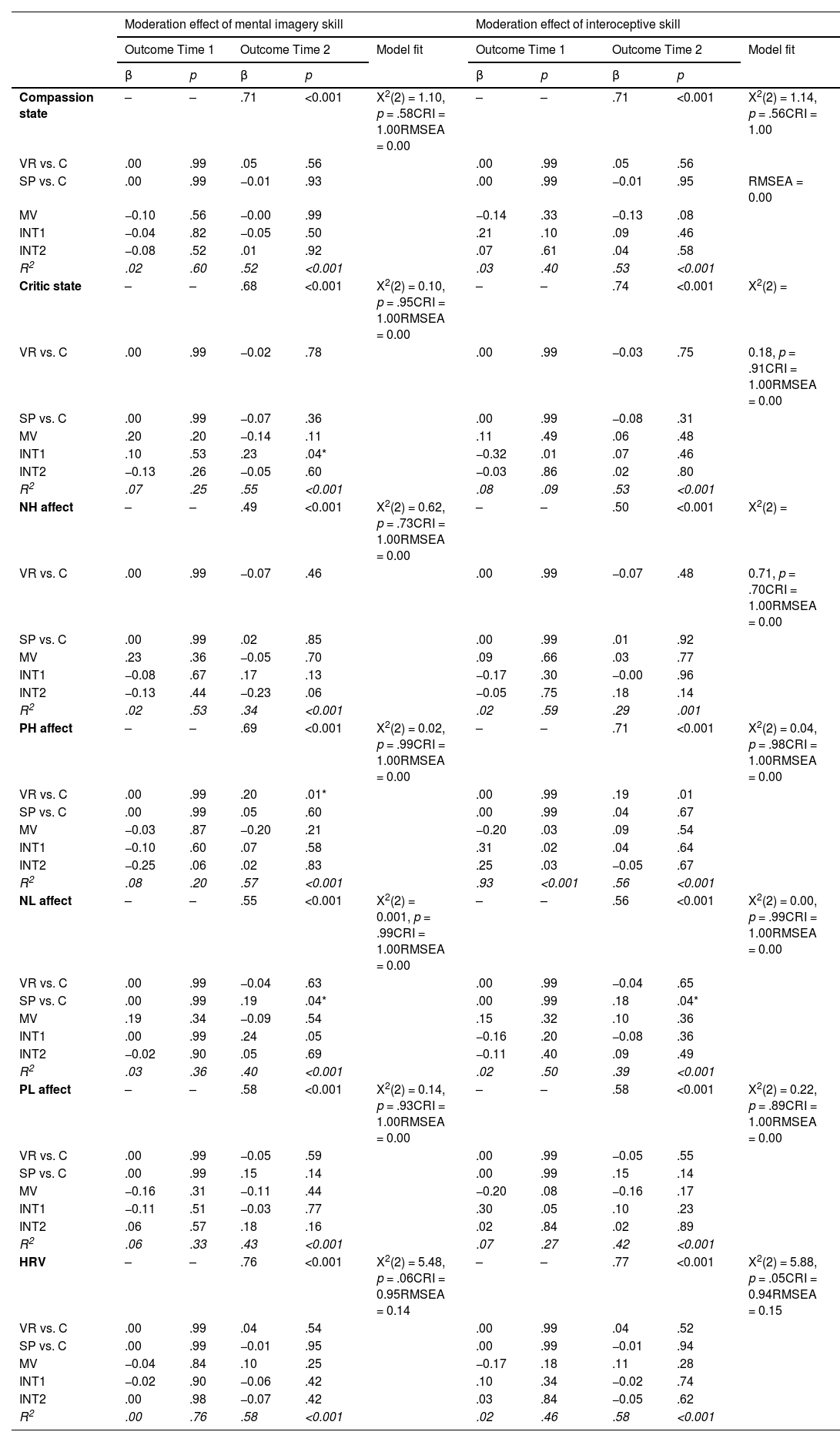

The interaction between mental imagery skill and group, specifically VR (dummy variable: VR vs. control), was only statistically significant for the criticism toward others variable (β = 0.23; p = .04), with the standardized beta indicating a small-to-moderate effect size (see Table 5). As shown in Fig. 6, at higher levels of mental imagery skill, the control group exhibited a greater reduction in criticism toward others than the VR group. However, at lower levels of mental imagery skill, the VR group showed a more substantial reduction in criticism toward others than the control group. Therefore, we may conclude that VR was beneficial only for participants with low mental imagery skills, leading to a significantly greater reduction in criticism towards others compared to the control condition. Although MLR estimation was employed as a robust alternative to address distributional problems, Fig. 6 shows the presence of an outlier in the VR group which, once removed, eliminates the statistical significance of the moderation effect. Consequently, we can only consider it as a potential moderator, which requires future studies for cross-validation. No significant interaction was found between interoceptive skills and the groups, as reported in Table 5.

Moderation effect of mental imagery skill and interoceptive skill in T1-T2.

Note: MV= moderating variable; NH= negative high arousal affect; pH= positive high arousal affect; NL= negative low arousal affect; PL= positive low arousal affect; HRV= heart rate variability; VR= virtual reality; SP= somatosensory priming; C= control; SD= standard deviation; INT1= Interaction of the VR group with the moderator; INT2= Interaction of the SP group with the moderator.

* = p<.05.

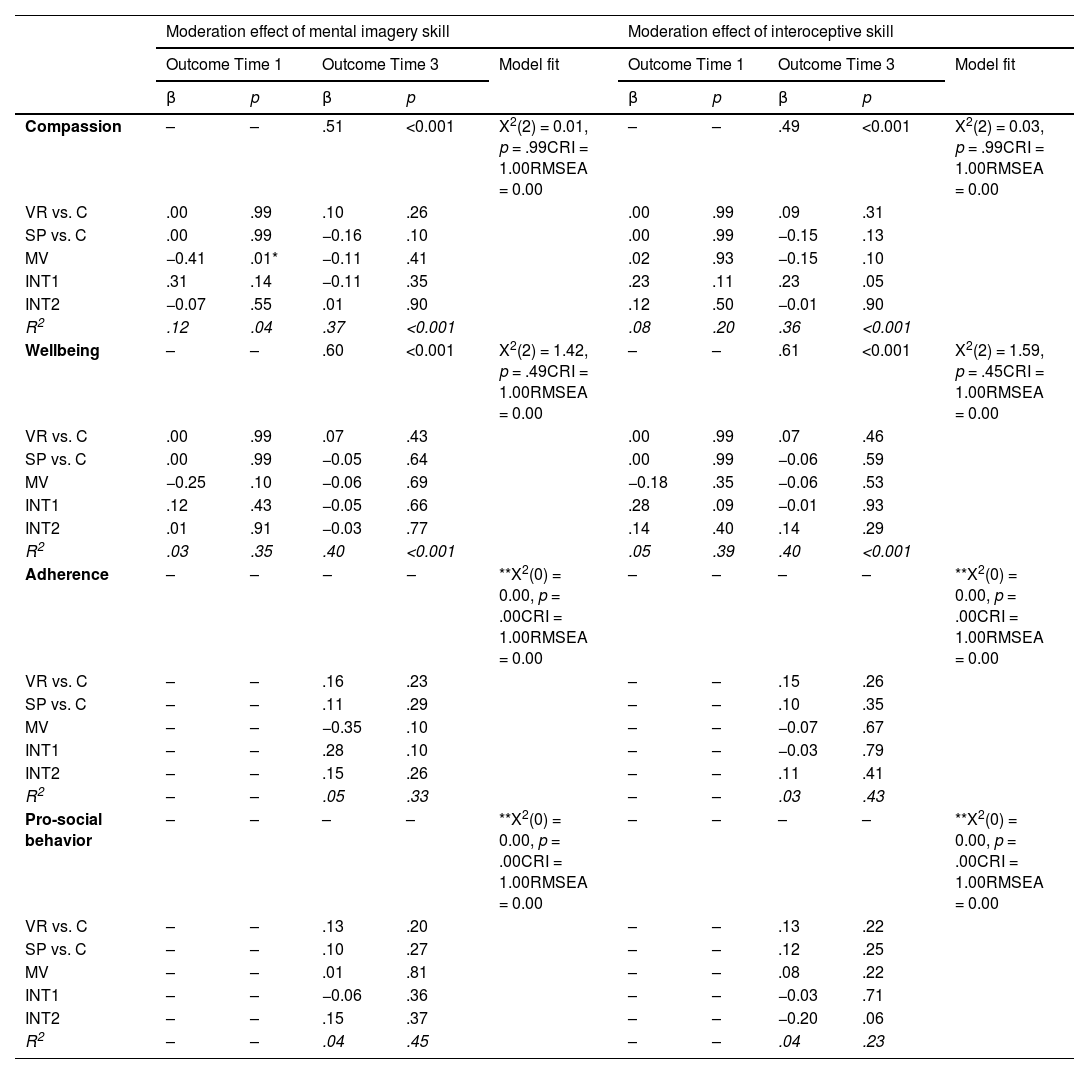

No significant interactions were found between mental imagery skill or interoceptive skills and the groups in any of the outcomes considered after two weeks, as shown in Table 6.

Moderation effect of mental imagery skill and interoceptive skill in T1-T3 and in T3.

Note: MV= moderating variable; VR= virtual reality; SP= somatosensory priming; and C= control. INT1= Interaction of the VR group with the moderator; INT2= Interaction of the SP group with the moderator.

**Models for Adherence and Pro-social behavior are saturated models without degrees of freedom because there is no pre-intervention measure of these variables.

* = p<.05.

Compassion-based interventions have shown very promising levels of effectiveness across a variety of applications (Gilbert, 2020; Kirby et al., 2017; Klimecki et al., 2013). However, developing compassion can be challenging for some individuals, since it demands both effort and the acquisition of specific skills (Gilbert, 2009). Compassion can be cultivated through two approaches: including cognitive processes, following a top-down approach; and sensory experiences, with a bottom-up approach (Chiesa et al., 2013). In particular, the use of mental imagery and somatosensory perception, respectively, play a key role in ensuring the quality of compassion practice (Navarrete et al., 2021a). The results seem to show that VR and SP may facilitate compassion practice by compensating for difficulties in some of the key skills proposed by Gilbert (2009), such as mental imagery and sensory perception. This theoretical framework provides the basis for exploring the effectiveness of VR and SP in enhancing the benefits associated with compassion practice while exploring how individual differences in imagery and interoception skills affect outcomes. Overall, compassion practice was effective across all variables in short term and let to improvements in well-being in the longer term. However, our hypotheses regarding the specific group differences were only partially confirmed.

Firstly, our findings revealed that participants in the VR condition reported a significantly greater increase in high-arousal positive affect compared to the control group, which was unexpected. A recent meta-analysis (Luberto et al., 2018) suggests that compassion meditation enhances prosocial outcomes primarily by boosting positive affect. Most studies support this hypothesis, which shows that compassion practices foster positive emotions (e.g., Förster & Kanske, 2021; Kok et al., 2011). However, these studies often use traditional measures that do not distinguish between arousal levels. Research with more nuanced tools demonstrates that compassion practices typically increase low-arousal positive affect, such as calmness and serenity, without significantly affecting high-arousal positive affect, such as enthusiasm and dynamism (e.g., Kearney et al., 2014; Koopmann-Holm et al., 2013; Matos et al., 2017), which contradicts our findings.

One plausible explanation is the novelty, immersiveness, and enhanced engagement produced by VR technology (e.g., Merchant et al., 2014), which often elicits heightened enthusiasm and excitement, particularly among first-time users (e.g., Miguel-Alonso et al., 2024). Although we did not control for participants’ prior experience with VR, this VR-related effect may explain the divergence from typical results observed in non-VR compassion practice groups.

Secondly, while the reduction in high-arousal negative affect was similar across all groups, the SP group showed a smaller reduction in low-arousal negative affect compared to the control group, which is inconsistent with our hypothesis. While most evidence suggests that compassion practices reduce negative affect (Engen & Singer, 2014; Hofmann et al., 2011; Sirotina & Shchebetenko, 2020), some studies indicate that these practices can also increase sadness or overall negative affect (Di Bello et al., 2021; Zheng et al., 2023). Compassion, as Gilbert and his colleagues (2019) note, is not tied to a single emotion, but rather involves a range of affective states shaped by the situational context (Falconer et al., 2019). The increase in negative affect seems to be especially true for practices focused solely on others, that is, not incorporating self-compassion (Sirotina & Shchebetenko, 2020), such as TM in our study. These studies underscore the importance of clearly describing instructions and distinguishing among different families, taxonomies and/or phases of compassion practices to facilitate more accurate data interpretation. Besides, these results may also be explained by the increased somatic awareness, which in turn can heighten empathic resonance with others’ suffering, particularly in the SP group. This aligns with priming studies using warmth stimuli, where emotional connection with others after priming is usually enhanced (Williams & Bargh, 2008). Since emotional resonance with distress is a component of compassion (Strauss et al., 2016), this heightened connection could delay the reduction of negative affect. Recent studies on the phenomenology of empathic resonance also report increased negative affect associated with such experiences (Troncoso et al., 2024). This complexity emphasizes the need for validated tools to measure compassion and its five components, including empathy resonance, at the state level. Developing instruments aligned with Strauss’s theoretical framework and/or incorporating phenomenological interviews (e.g., Uygur et al., 2019) could offer a more granular understanding of the temporality and associated emotional changes during the practice.

Thirdly, regarding physiological measures, compassion practice increased HRV in all conditions. This finding is consistent with other studies which show that even a single compassion induction can produce physiological benefits through activation of the parasympathetic nervous system (Stellar et al., 2015). However, the tested enhancement tools were not more effective in increasing HRV than the control group.

One possible explanation may be attributed to a potential ceiling effect, as observed in other studies involving non-clinical populations, in which participants often exhibit high baseline levels of relaxation or calmness, leaving limited scope for improvement (e.g., Shaltout et al., 2012). Consequently, the capacity to detect significant changes in autonomic activity induced by the tools may be diminished. Future studies should explore similar designs with clinical populations.

Another potential explanation lies in the theoretical subdivision of the compassion process (Gilbert, 2019), which distinguishes between engagement (that is, focusing attention on suffering and committing to address it) and action (that is, initiating specific responses to alleviate suffering). This distinction is particularly relevant because recent studies show that HRV decreases during the engagement phase and increases during the action phase (Di Bello et al., 2021). Since the compassion meditation used in our study involves a continuous connection with both suffering and the willingness to alleviate it, it was not possible to distinguish between these two phases. Future research should use experimental designs that distinctly measure these phases during meditation practices, thus providing a more nuanced understanding of the physiological mechanisms underlying compassion and their potential modulation by targeted interventions.

Fourthly, regarding the two-week follow-up assessment, the only significant increase observed across all groups was in well-being. However, no significant differences were detected among the groups for any of the follow-up variables. This suggests that the short-term effects of the enhancement tools did not persist beyond the single session. In the case of SP, no similar studies exist to compare our results.

However, our findings are aligned with other recent studies of VR. For instance, the use of VR in compassion practice, whether in a single session (Cebolla et al., 2019) or on a weekly basis over a six-week program (Modrego-Alarcón et al., 2021), did not enhance the benefits of the meditation at the long term. It is possible that the enhancement tools would need to be integrated into each meditation session rather than used as a support tool (once or on a weekly basis). Alternatively, these enhancement tools may not produce medium-term effects on psychological or behavioral variables, which would suggest that sustained use may be necessary to observe meaningful changes. Future research should consider the use of low-cost VR devices (Coburn et al., 2017) to test the effectiveness of these enhancement tools in the context of daily home practice. In addition, highly sensorized applications in VR (see Guillen-Sanz et al., 2024 for review) could represent the next step in compassion research. Integrating wearable sensors and biofeedback within immersive VR environments could enable clinicians to enhance compassion-based practices through more individualized interventions. Indeed, during compassion exercises, some individuals, particularly those with high self-criticism or insecure attachment styles, may experience negative responses to the practice (e.g., sympathetic nervous system activation; Naismith et al., 2023; Rockliff et al., 2008). In these cases, wearable biosensors could help monitor physiological responses in real time and support attentional redirection, promoting activation of the parasympathetic branch of the nervous system. This, in turn, could allow for more personalized support and increase the likelihood of achieving desired long-term outcomes.

Finally, the exploratory analyses examining individual differences in mental imagery and interoceptive skills provided important insights into how VR and SP can be used to enhance compassion practice. Potentially, only individuals with low mental imagery skills would show reduced criticism toward others when using the VR tool. The results seem to indicate that VR may be particularly effective for individuals with low imagery skills, which might be explained by the VR characteristics that the system offers (by providing immersive “prefabricated” visualizations) to support human mental imagery processing. Specifically, according to Pearson and his colleagues (2013), mental imagery involves four core skills: generating, maintaining, inspecting, and transforming images, which all can be supported by VR. First, image generation through the visual buffer (Kosslyn, 1980) becomes unnecessary, since VR automatically creates and presents the representations. Second, maintenance, which requires continuous reactivation (due to the images decaying within approximately 250 ms; Kosslyn, 1994), is facilitated, as VR projects vivid representations in a constant manner. Third, image inspection, understood as directing attention to different parts of the representation held in the visual buffer to encode its geometric properties (Kosslyn, 1994), becomes more straightforward thanks to the perceptual stimuli already embedded in the virtual environment. Finally, transformation (understood as the mental rotation of an image through modulation of the subsystem that processes object properties; Kosslyn et al., 2006), can be externalized in VR via dynamic changes in the simulation, thereby simplifying a cognitively costly process. Furthermore, research shows that a first-person perspective, which is the one provided by VR, compared to a third-person perspective, increases the potential to generate affective states (Holmes et al., 2008). Therefore, amplifying the emotional aspect of the compassion meditation. In sum, by providing more concrete, detailed, stable, visually transformable, and first-person images, VR compensates for potential limitations of cognitive processing and potentially enhances the effectiveness of CBIs (Navarrete et al., 2021a). Taken together, this theoretical account and our data suggest that, individuals with poorer mental imagery abilities show greater reductions in criticism toward others when using VR. Mental imagery has been described as a key mechanism of emotional change and an important target of clinical interventions (Holmes et al., 2015; Pearson et al., 2015). In this line, Holmes and her colleagues (2015) propose that mental imagery operates as a weaker form of perception, that relies on similar neural systems and overlaps with visual working memory. Therefore, individuals with more vivid imagery can draw more effectively on these processes for cognitive and emotional processing, whereas those with more limited mental imagery skills may particularly benefit from VR. In our study, VR appears to compensate for these limitations by providing vivid, stable, first-person affiliative cues that “outsource” the cognitive work of generating and maintaining compassionate mental images, which in turn has an impact on criticism outcome.

Beyond this possible mechanism, empirical evidence directly linking mental imagery skills with compassion and criticism toward others remains limited. To the best of our knowledge, no study has specifically examined these specific variables’ relationship. However, some empirical results can help us interpret these findings. Specifically, recent meta-analyses have identified self-criticism as an important transdiagnostic variable that is impacted by CBI (Kirby, 2025; Petrocchi et al., 2024; Vidal et al., 2023; Wakelin et al., 2022). Others showed that individuals with high levels of self-criticism tend to have difficulties generating compassionate mental representations toward themselves (Gilbert et al., 2006). Although these studies focus on self-criticism (and not criticism toward others), it could be that individuals with high levels of criticism toward others may also struggle to generate compassionate images directed toward other people. In this way, VR might be understood as a tool to enhance mental imagery and therefore having an impact on specific emotional variables such as criticism. Nevertheless, more evidence focusing specifically on criticism toward others and its relationship to mental imagery skills in contemplative practice is needed before any conclusions can be drawn. In sum, while VR has been recognized as a promising tool for cultivating compassion, it has not consistently shown significant advantages over control groups (Žilinský & Halamová, 2023). Our findings challenge the assumption that VR might only partially enhance compassion practice, thus demonstrating that it does have an effect, but only for individuals with low mental imagery skills.

Regarding the interoceptive skills, no moderation effects were observed across any of the outcome variables. To the authors’ knowledge, no previous studies have directly examined interoception as a moderator in CBIs. Nonetheless, prior literature has linked interoceptive processes to outcomes central to compassion-related change, such as emotional resonance (Ernst et al., 2013; Grynberg & Pollatos, 2015), which contradicts the results of this study. Indeed, contemplative programs including body-focused and compassion practices, such as the ReSource Project, have shown increases in interoceptive awareness (measured with both, the full MAIA scale and a single body awareness item) (Bornemann et al., 2015; Kok & Singer, 2017). This lack of moderation effect may therefore reflect the complexity of how interoception is conceptualized and measured rather than the absence of its relevance. In recent years, interoception has increasingly been recognized as a multidimensional construct. Garfinkel et al. (2015) proposed a widely cited tripartite model that distinguishes between interoceptive accuracy (objective performance), interoceptive sensibility (subjective self-report), and interoceptive awareness (metacognitive insight, i.e., the correspondence between confidence and accuracy). Recent reviews not only emphasize that these dimensions are often poorly correlated but also show that different self-report instruments capture distinct and weakly related aspects of interoception, leading to low intercorrelation among questionnaires (Desmedt et al., 2023, 2022).

In this context, the discrepancy between our results and previous findings may stem from differences in measurement methods. Whereas the previous studies assessed interoceptive accuracy through objective tasks (e.g., heartbeat counting or detection) (Ernst et al., 2013; Grynberg & Pollatos, 2015), our study focused on interoceptive sensibility, using only the neutral bodily sensations subscale of the ISAQ. While valid, this subscale may not adequately capture the emotionally relevant dimensions of interoception involved in compassion-based practices. Therefore, future studies may benefit from using more targeted subscales, such as Emotional Awareness subscale from the MAIA (Mehling et al., 2012), which assesses the extent to which individuals recognize the connection between bodily sensations and emotional states, an aspect that reflects greater body-emotion integration, and may be more sensitive to moderation effects in this context.

LimitationsThis study is the first to test two different enhancement tools (VR and SP) in compassion practice within a fully-powered randomized control design, using self-reported, physiological and behavioral measures. Another key methodological strength is the inclusion of an active control group, which is often lacking in contemplative science (Kreplin et al., 2018). Following recommendations for psychological intervention trials (Mohr et al., 2009), the active control was structurally similar to the experimental conditions, thereby reducing threats to internal validity by accounting for nonspecific factors such as attention or time. This design allowed us to examine the added value of the enhancement components (VR and SP) beyond the effects of the compassion practice itself, rather than comparing the interventions to a passive or no-treatment condition. While this approach may attenuate between-group differences and require larger samples, it strengthens causal inferences about the specific contribution of the enhancement tools and addresses common criticisms in the field. That said, some limitations should be considered. Firstly, the study uses an adapted measure of compassion and criticism toward others from self-related compassion and criticism questionnaire (Falconer et al., 2015). Although both sub-scales showed good internal consistency, future psychometric validation of the adapted scale would provide more robust conclusions. Secondly, while the literature supports the theoretical mechanisms (both somatosensory and mental imagery) could through which different tools benefit practice (e.g., Navarrete et al., 2021a), these mediational mechanisms were not tested in this study. Future studies should examine how VR and SP influence the visual and somatosensory components of practice quality, for instance, by assessing them through the specific compassion quality scale (Navarrete et al., 2021a) which captures both dimensions, and by investigating how these components, in turn, mediate the relationship between the enhancement tools and the outcome variables. Thirdly, the study does not control for the subjective perception of the warmth felt by participants in the SP condition. Fourth, although participants were unaware of the use of VR during the selection process for the study, which rules out technology-related selection bias at recruitment, some degree of self-selection cannot be excluded. Motivation to participate may have been influenced by prior interest in meditation or by financial compensation. Although financial incentives have been shown to increase compliance in ecological momentary assessment (EMA) studies (Ludwigs et al., 2020; Wrzus & Neubauer, 2021), this effect is unlikely to bias the results, as all groups received the same compensation, which was tied only to EMA responses rather than meditation practice. Fifth, adherence was assessed as a self-report measure only. Although this method provides a straightforward estimate of the practice frequency, it may also be subject to bias. Finally, the sample was limited to the city of Valencia and surrounding areas, with mostly highly-educated, Caucasian participants, making the results not generalizable to other populations.

Clinical implicationsAlthough the effect sizes were small to moderate and derived from a non-clinical sample, the findings provide valuable clinical insights, showing that tools such as VR and SP can enhance and personalize CBIs. A key result was that mental imagery skills moderated the effects of VR. This could be particularly relevant for highly self-critical individuals, a population associated with greater psychopathology (e.g., Cox et al., 2004; Gilbert, 2014) and characterized by more difficulties in generating compassion-related images (Duarte et al., 2015; Gilbert et al., 2006), which makes them ideal candidates for future research with VR. In this sense, it is not only necessary to consider low mental imagery skills in general, but also to pay specific attention to clinical populations with high self-criticism, for whom the integration of this technology could be especially useful.

Clinicians might therefore consider assessing mental imagery skills prior to the intervention or introducing these techniques when limited reductions in interpersonal criticism are observed. Such adaptations could increase both the accessibility and the effectiveness of CBIs, particularly for those who experience greater barriers to engaging with these practices. Nevertheless, these recommendations should be interpreted with caution, as this is the first study to identify such moderation effects. Therefore, future studies should replicate these findings within longer, validated compassion-based interventions (e.g., Goldin & Jazaieri, 2020) and extend them to clinical populations, in order to confirm their scope and applicability.

Moreover, since no significant between-group differences were observed at follow-up, the results point out toward the fact that more sustained meditation practice with the enhancement tools might be needed. Indeed, the lack of significant between-group differences at follow-up is consistent with previous studies (e.g., Cebolla et al., 2019; Navarrete et al., 2021a). Therefore, it remains unclear whether these tools can produce long-lasting effects after sustained practice, and more fully powered studies are needed to establish if repeated use of the enhancement tools is necessary to achieve longer-term therapeutic benefits.

Overall, these findings provide a promising basis for developing more individualized protocols that integrate technologies such as VR and SP into clinical contexts, although further research is needed to evaluate their long-term efficacy and sustainability.

Future directionsLooking ahead, future studies should not only replicate these findings but also examine the impact of VR, SP and other enhancement tools in more diverse and clinical populations, including individuals with specific characteristics (i.e., low mental imagery skills, depressive symptomatology, insecure attachment style and high self-criticism), to determine the most effective approaches. Moreover, it would be useful to examine more precisely the mechanisms through which VR and SP enhance compassion practice. For example, to assess the visual and somatosensory components of practice quality using specific measures (such as the CPQS; Navarrete et al., 2021a) and to analyse whether these components mediate the effects of enhancement tools on outcome variables. It will also be important to complement self-report measures with physiological markers (e.g., EEG) that provide indicators of underlying processes, as well as with measures that explore the subjective experience of meditation and haptic warmth (Lynott et al., 2023), such as phenomenological interviews (Bevan, 2014). In addition, systematically assessing variables such as familiarity with VR (Lehikko et al., 2025) would help to better understand the impact of sensory priming and VR from an idiographic perspective. Additionally, the use of digital practice logs could also be considered to allow a more accurate estimation of adherence, minimizing recall problems and social desirability biases. In turn, incorporating brief in-app assessments of the degree of engagement would help to more finely characterise the impact of practice quality. Finally, future trials should include longer interventions and follow-up periods, in order to clarify the generalisability and long-term impact of integrating VR and SP into compassion-based interventions.

ConclusionsThe findings of this study add to the state of the art regarding the effectiveness to compassion practice. The study provides evidence that compassion practice is effective across groups, with consistent improvements in self-reported and physiological outcomes in the short term, and enhanced well-being at two-week follow-up. The exploratory analysis also revealed that VR was beneficial for individuals with low mental imagery skills, demonstrating greater reductions in criticism toward others. These findings highlight the relevance of tailoring CBIs to individual characteristics, especially mental imagery skills, when considering the integration of different types of enhancement tools. In doing so, they open promising avenues for the development of more personalized and clinically impactful interventions that can extend the reach and effectiveness of compassion-based practices.

Future studies should build on these results not only by replicating current study, but also by examining the impact of these and other types of enhancement tools in clinical populations, including individuals with specific characteristics (i.e., low mental imagery skills, depressive symptomatology, insecure attachment style and high self-criticism) to determine the most effective approaches.

StatementDuring the preparation of this work the authors used DeepL Write and ChatGPT to improve the readability and language of the manuscript. After using these tools/services, the authors reviewed and edited the content as needed and take full responsibility for the content of the published article.

FundingThis work was supported by the Spanish Ministry of Science and Education within the Beatriz Galindo Excellence Research grant (BEAGAL18/00111) and the Scientific. Excellence for Junior Researchers grant (CISEJI/2022/46), both received by MW. This work was also supported by the Generalitat Valenciana (CIPROM/2021/041) under which DC is contracted, and María Zambrano postdoctoral grant from the Ministry of Universities of the Spanish Government (ZA21–056) received by CA.

Data availabilityThe dataset is available on: Palacios Macián, Aida (2024). “Tonglen Dataset”, Mendeley Data, v1, 2025, doi:10.17632/gffbgxvcmb.1.

CRediT authorship contribution statementAida Palacios: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Sara Martínez-Gregorio: Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – review & editing. Catherine Andreu: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Desirée Colombo: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ausiàs Cebolla: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Rosa Baños: Conceptualization, Resources, Writing – review & editing. Maja Wrzesien: Project administration, Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Resources, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

We would like to express our sincere gratitude to all the participants for their valuable contributions during the data collection process. Our heartfelt thanks also go to the developers of the Virtual Reality system—Inmaculada Remolar Quintana, Ignacio Miralles Tena, and Jon Andoni Fernández Moyano—for their expertise. Lastly, we would like to extend our sincere appreciation to Daniel Balboa for his dedication and technical assistance throughout the project.