The cooperation of companies in networks is a strategy used by managers to act in their business sector, aiming to add more value to their companies and create competitive advantage. The literature on this topic exposes many benefits of acting collaboratively in networks, but little is known about the factors that lead companies to withdraw from horizontal networks. This paper aims to investigate which factors drive companies to leave interorganizational networks. In order to do this, we conducted a qualitative research with seven interorganizational networks from which companies were withdrawing. Data was collected by interviewing the presidents of these seven networks and the owners of 11 companies that withdrew from them. The results outline a set of factors that lead companies to leave networks. Among the most cited are: lack of criteria for member selection, lack of trust, lack of commitment, and opportunism and individualism of some of the members. We concluded that most of these factors are intrinsically related and result in limiting the potential of the network to add value and obtain higher possibilities of competitive advantage for its members.

It is increasingly possible to verify the development of networks as alternatives for the maintenance and growth of companies. The importance of this development is visible in small- and medium-sized businesses that cannot act alone and find difficulties acting in the market due to significant competition. Small businesses are more vulnerable to the effects of globalization and struggle with absorbing both technological and managerial innovations, as well as with developing innovative products. Interorganizational networks may mitigate such difficulties and other resource limitations of small organizations.

Popp, Milward, Mackean, Casebeer, and Lindstrom (2014) suggested that the creation of interorganizational networks can be a useful strategy for organizations perceiving a need to develop a structure that is more nimble and able to create change and/or be more responsive to change compared to bureaucratic organizations. Numerous benefits of such a structure are described in the literature (such as shared risk, advocacy, positive deviance, innovation, flexibility, and responsiveness). According to Håkansson and Snehota (1989), no organization is an island: every organization needs relationships with other organizations to survive and grow.

Interorganizational networks – the focus of this study – are generally formed when two or more organizations collaborate to share resources with a common goal, seeking to improve their performance in response to a threat to their development from the environment, without a predetermined period of existence. They are formed at a specific time to perform network activities and set clear limits for organizations that are recognized as members of the network (Wincent, Thorgren, & Anokhin, 2014). These organizations work together under certain rules, but remain independent in the market, which allows them to maintain a certain degree of flexibility. The formalization of this partnership constitutes a strategic decision by organizations seeking to exchange resources and gain a competitive advantage that they could not obtain alone (Child & Faulkner, 1998; Senge, Lichtenstein, Kaeufer, Bradbury, & Carroll, 2007).

However, currently, the structure and management of networks raises new questions. Chao (2011) explained that collaboration in business networks can be considered a series of decision-making processes involving interactions between companies. In this context, insufficient understanding of the parties or lack of commitment can lead to a variety of biases and errors, affect the stability of the cooperative process, and in some cases, the continuity of the network. Apparently, the formation and development of business networks is related to members’ interests in achieving a positive relationship of benefits versus costs from the collaborative strategy. However, when that relationship becomes unfavorable, companies participating in the network question the creation of the group (network) and whether they should remain in it. Furthermore, a significant number of companies leave cooperative arrangements such as interorganizational networks (Klein, 2012) and even end these collaborative arrangements (Baker, Faulkner, & Fisher, 1998; Inkpen & Beamish, 1997). Therefore, if networks actually provide benefits and competitiveness as discussed earlier, why do some companies withdraw from them? What are the reasons that lead to this decision? Finding the answers to these questions is precisely the objective that motivates this study and challenges the research on this topic.

In some cases, networks are unable to consolidate their structures and management models. However, some aspects (such as opportunism or a lack of goal congruence, trust, or commitment) can influence the performance of activities undertaken by networks. These aspects emerge in networks to the point at which they no longer justify the investments made by member companies. These are issues that are rarely discussed in the literature on the topic; thus, in an attempt to fill this gap, this study aims to investigate which factors lead companies to withdraw from interorganizational networks in which they were embedded.

Klein and Pereira (2012) argued that academic research has proposed prominent analyses of the success of cooperative arrangements, but few studies are concerned with understanding why many companies withdraw from cooperation arrangements and why many of these networks fail. Verifying problems and aspects that lead partner companies to abandon the collaborative process and leave networks may help in the management of interorganizational networks and mitigate difficulties that arise during their development. Moreover, according to Chen (2010), studying these aspects and problems in interorganizational networks may be significant for improving their performance and facilitating their continuity.

Types of interorganizational relationshipsIn the study of relationships, researchers must consider that as individuals can benefit from social capital due to their relationships (Coleman, 1988), organizations can also benefit from their relationships with other organizations (Galaskiewicz, 1985). Given the possible benefits that can be obtained, companies collaborate with one another, and interorganizational relationships arise.

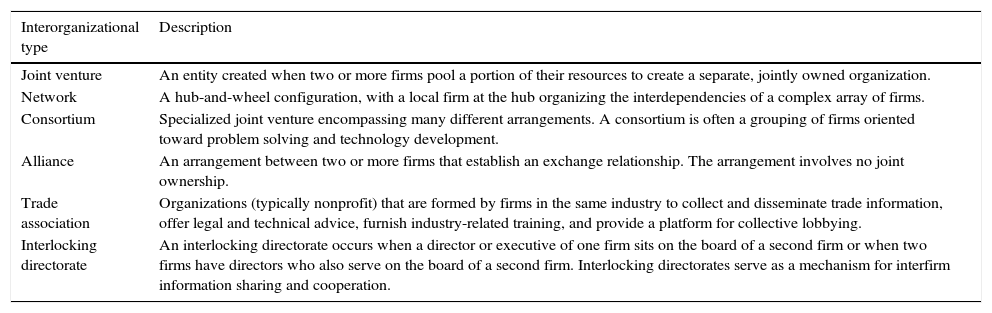

Parmigiani and Rivera-Santos (2011) explained that interorganizational relationships exist under a variety of forms, including alliances, joint ventures, supply agreements, licensing, co-branding, franchising, intersectoral partnerships, networks, associations, and consortia. Similarly, Barringer and Harrison (2000) addressed and explained different types of interorganizational relationships. Table 1 shows some of the most common types of interorganizational relationships.

Types of interorganizational relationships.

| Interorganizational type | Description |

|---|---|

| Joint venture | An entity created when two or more firms pool a portion of their resources to create a separate, jointly owned organization. |

| Network | A hub-and-wheel configuration, with a local firm at the hub organizing the interdependencies of a complex array of firms. |

| Consortium | Specialized joint venture encompassing many different arrangements. A consortium is often a grouping of firms oriented toward problem solving and technology development. |

| Alliance | An arrangement between two or more firms that establish an exchange relationship. The arrangement involves no joint ownership. |

| Trade association | Organizations (typically nonprofit) that are formed by firms in the same industry to collect and disseminate trade information, offer legal and technical advice, furnish industry-related training, and provide a platform for collective lobbying. |

| Interlocking directorate | An interlocking directorate occurs when a director or executive of one firm sits on the board of a second firm or when two firms have directors who also serve on the board of a second firm. Interlocking directorates serve as a mechanism for interfirm information sharing and cooperation. |

Source: Barringer and Harrison (2000).

Table 1 provides examples of types of interorganizational relationships formed by companies aiming to obtain benefits and competitive advantage from the relationship. Considering networks in particular, it is necessary to clarify that the formation of a network arrangement may be created in vertical or horizontal configurations (Gulati & Gargiulo, 1999); therefore, networks can generally be classified as fitting one of two typologies: vertical networks and horizontal networks. The first is formed by vertical links between organizations, considering their supply chain. These relationships involve organizations from different sectors of the chain that are connected to one another sequentially (for example, producers, wholesalers, retailers, and consumers) (Lazzarini, 2008). The second typology, horizontal networks, is formed by relationships among organizations at the same level of the supply chain (for example, only retailers) that remain legally independent in the market (Wegner & Padula, 2010), but cooperate to conduct a business activity. Example activities include the production of a product, product promotion, or organizing the distribution of a product (Perry, Sengupta, & Krapfel, 2004). The member organizations of this type of network try to reduce their shortcomings in terms of resources by obtaining joint benefits to become more competitive.

This study focuses on horizontal networks. In summary, they present the following main characteristics: (1) They are formally constituted organizational arrangements; (2) They do not have a fixed period of existence; (3) They seek to achieve the objectives of members as well as of the network; (4) Decision-making is usually undertaken jointly within the membership; and (5) They have an organizational structure that is independent from the structure of their member companies.

Challenges in horizontal networksAs previously noted, organizations can obtain benefits and competitive advantages by establishing relationships with other organizations such as those relationships in horizontal networks. However, cooperation with other companies at the same level of a specific business sector through a network requires investment, time, and resources for its implementation, as well as negotiation of norms and procedures for its continuity (Wegner & Padula, 2010). Furthermore, commitment and trust from partner companies are required to maintain the network's management system and coordinate the relationship (Parast & Digman, 2008). According to Pesämaa (2007), many companies are not geared toward collectivism and do not appreciate the disadvantages/costs of being grouped into networks. Therefore, they are not able to assess whether they are able to join the network or whether such a strategy is positive for them.

In horizontal networks, a set of processes and procedures is needed to define the direction of the network and allow the allocation of efforts and resources to achieve the predefined objectives. Concerning these aspects of management, Sydow (2006) noted that compared to an individual organization, the management of interorganizational networks implies significant changes in the functions and roles of traditional management. Managers cannot be concerned solely with developing and implementing strategies and innovations for their individual company; they also have to formulate and implement collective strategies that meet the interests of all members of the network.

Other issues are also involved in the development and management of horizontal networks, such as costs of cooperation (Adler & Kwon, 2002), information asymmetry and opportunistic behavior (Willianson, 1985), transfer of knowledge (Larson, Bengtsson, Henriksson, & Sparks, 1998; Yayavaram & Ahuja, 2008), different learning capabilities and values (Hamel, 1991; Hibbert, Huxham, Sydow, & Lerch, 2010), and lack of value creation (Ahola, 2009).

Other problems and challenges that arise in horizontal networks are related to the inflexibility of network members in relation to their geographic area. The distance from one member to another can hinder access to new markets and the manufacturing of similar products. Additionally, each geographic region has its own characteristics, which makes it difficult to apply common actions and procedures to all network members. Moreover, an important factor that must be managed by the network is the existence of asymmetric incentives among members, which inevitably arise as the alliance evolves (Olson, 1971). Goals that were common may lose some of the sense of urgency to some members over time, thereby reducing their desire to cooperate (Khanna, Gulati, & Nohria, 1998); in connection with this phenomenon, the strategic advantage of an organization belonging to a network also tends to fade away over time. Ultimately, belonging to a network is no longer sufficient to guarantee business sustainability for network members (Pereira, 2005).

Additionally, the complexity of coordinating network transactions and activities may increase to the point that not all members realize the same benefits. Furthermore, the cost of the relationship increases and exceeds the benefits derived from the network, thus failing to justify continued membership.

The aspects shown in this subtopic of the article include challenges and problems mentioned in the literature of interorganizational networks that may influence the exit of organizations from networks. In order to address these issues, the next subtopic shows the reference framework built to conduct the empirical application of this study.

Reference frameworkZineldin and Dodourova (2005) stated that, in general, studies on cooperation between companies fail to use clear indicators to distinguish success and failure in strategic relationships. Although there is no consensus on the reasons that lead companies to leave the network to which they belonged or explanations that lead to the failure of the network, the factors that lead to success may provide important indications. Thus, different theoretical models and studies were consulted to provide a reference framework for this study, such as Sadowski and Duysters (2008), Chao (2011), Corsten, Gruen, and Peyingaus (2011), Mccutchen, Swamidass, and Teng (2008), and Pesämaa (2007). These models and the literature described earlier were reviewed to understand variables and aspects that may affect the topic of this study. Although some studies are related to dyadic relationships, they demonstrate potential to be referenced in this study.

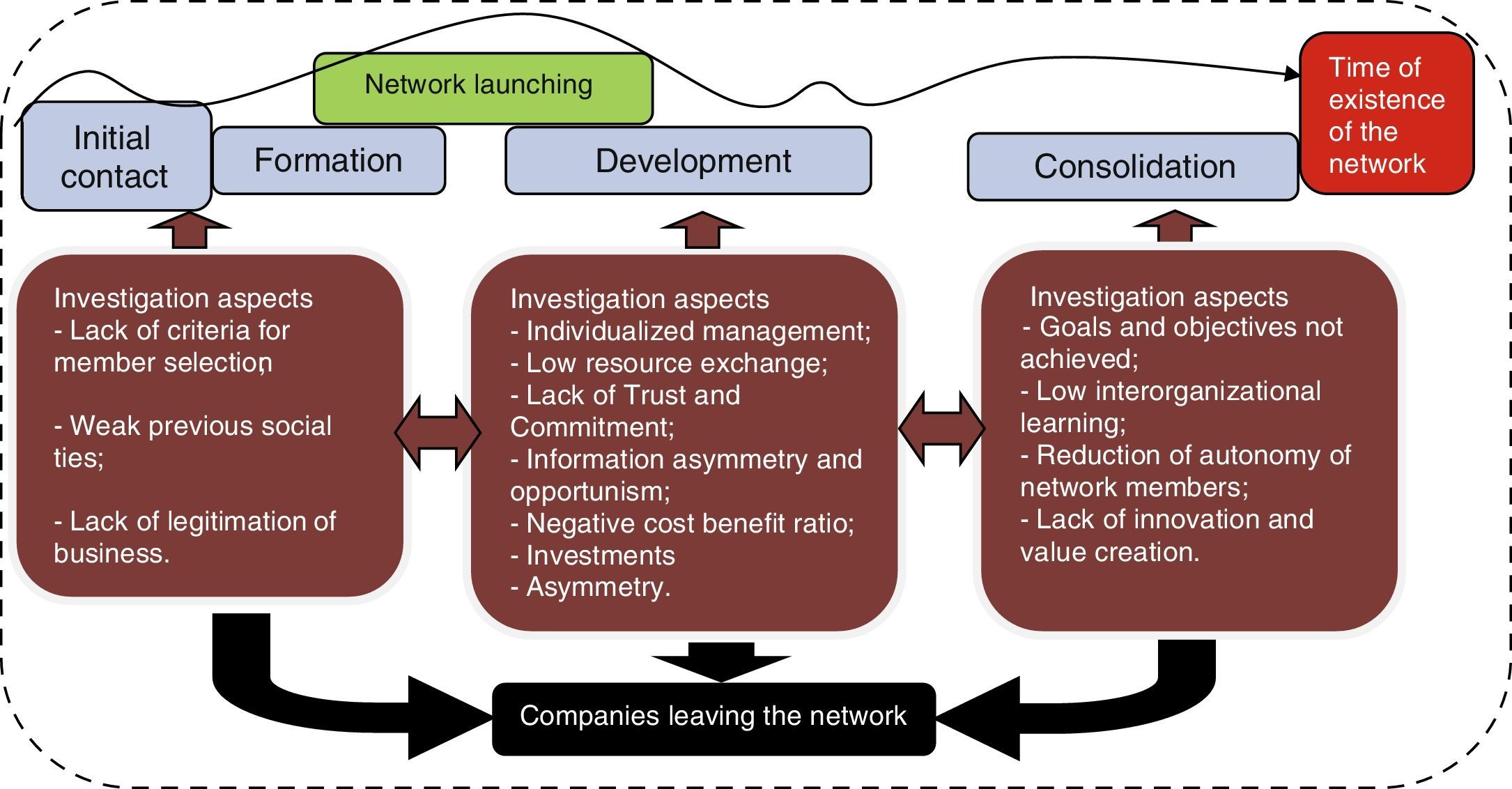

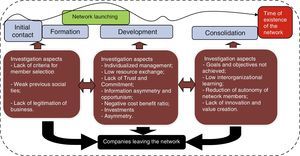

The proposed framework was specifically elaborated as a basis to develop this article, and follows the model of Chen (2010). Chen explored determinant aspects of perceived effectiveness of interorganizational collaborations in three stages of network development (the same stages used in the framework of this paper). The framework, derived from the theoretical proposal outlined by Klein and Pereira (2012), is shown in Fig. 1.

This framework facilitates the study of factors related to interorganizational networks in three distinct stages. These stages include: (1) “Initial Contact and Formation of the Network” – the stage of initial contact between network members, identification of their features and capabilities, and recognition of potential collaboration opportunities, problems, and difficulties; (2) “Development of the Network” – the stage involving the collaborative processes, the definition of standards and rules of conduct, and design of joint activities; and (3) “Consolidation of the Network” – the stage concerning the perceived results of the collaboration.

It is worth noting that some of the factors listed in each of the stages may be present in more than one stage, as is the case of trust and commitment, which are crucial during all cooperative processes. However, to organize the subsequent analysis, each point was mentioned only once.

The aspects included in the first stage focus on the history of the formation or creation of the network and reflect the next steps in strengthening the network. At this stage, the study focused on member selection, previous social ties, and organizational legitimacy. Aspects placed in the second stage consider collaboration, a dynamic process in which partners increase the sharing of information, resources, and mutual respect (Doz, 1996; Oliver, 1990). At this stage, the collaboration process consists of multiple dimensions, including shared management, resource sharing, building trust and commitment, the costs to maintain the network, and the possibility of asymmetry of investments and opportunism. Studies on the third stage identify the main results of the collaboration; for example, whether collaboration achieved its objectives and resulted in the improvement of organizational learning.

According to Bingham and O’Leary (2008), few studies link antecedents and preconditions that motivate the formation of networks, the processes in the development stage, and the results of collaboration. In the framework of this study, there are some points for companies to consider when deciding whether to join or to remain in an interorganizational network. These various aspects have influenced the performance of interorganizational networks.

Considering the theoretical aspects exposed here, we conducted the study empirically. The elements exposed in Fig. 1 gave us a starting point from which to explore this topic in the field, but the research was not limited to them. In the next section we explain the methodological characteristics and procedures used to accomplish this work.

MethodThis article is characterized as an exploratory study because it seeks to explore and understand a problem in depth, advancing knowledge on the topic, expanding existing studies from new perspectives, and discovering new relationships (Sampieri, Collado, & Lucio, 2006; Selltiz, Wrightsman, & Cook, 1972). The present study is also characterized by a qualitative approach. We chose this approach because it is an appropriate way to understand the nature of a social phenomenon (Denzin & Lincoln, 2006) and because it provides better visibility for the topic being investigated (Richardson, 1999).

The data collection procedure was conducted via semi-structured interviews. This tool was chosen because it allows for a more detailed investigation of a topic by having a flexible structure consisting of open questions in the area to be explored (Britten, 1995). Moreover, it offers the prospect of participants having the freedom and spontaneity necessary to enrich the research (Triviños, 1987). The development of the interview script was based on the variables exposed in Fig. 1.

There are two units of analysis in this study: (1) coordination and management of the networks that were analyzed, and (2) organizations that withdrew from the networks. The choice of two units of analysis was deemed necessary and appropriate to allow the obtaining of information from two different perspectives (from presidents of the networks and from owners of companies that left those networks) in order to understand what factors drive companies to leave networks.

A set of interviews was developed to help gain an understanding of the problems and issues related to the exit of member companies from the networks. For the first unit of analysis, we interviewed the managers or presidents of seven networks in the following fields of activity:

- •

1 Network of Electrical Material Companies;

- •

1 Network of Building Material Companies;

- •

2 Networks of Supermarkets;

- •

1 Network of Clothing Industry Companies;

- •

1 Network of Bakeries;

- •

1 Network of Pharmacies.

It is important to highlight that our focus was to identify general reasons for withdrawal and not reasons specific to each network. In other words, our approach did not intend to emphasize factors found in each network, but rather to draw a more general perspective.

For the second unit of analysis, we interviewed 11 business owners of companies that withdrew from these networks. We tried to interview at least one business owner from each of the selected networks to avoid interviewing owners from only one network. Interviews with the presidents and owners were held in different locations (some in their workplaces and some in their residences). To facilitate later analysis of transcripts, the presidents interviewed in this study were designated NP1, NP2, NP3, NP4, NP5, NP6, and NP7. These interviews lasted approximately 60min each. The business owners interviewed were identified as BO1, BO2, BO3, BO4, BO5, BO6, BO7, BO8, BO9, BO10, and BO11. These interviews were more succinct because the participants were not asked about the formation and purposes of the selected networks (this had already been asked when we interviewed the presidents and managers of these networks). Therefore, they lasted an average of 25min.

The networks and the participants were chosen so as to include responses from presidents and company owners of different business sectors. We only chose networks from which organizations were withdrawing; this choice was made because we were interested in identifying problems and aspects that had influenced organizations in their decision to leave. We also only interviewed the owners of organizations that withdrew from the networks because they could specifically state their reason(s) for doing so. All interviews were recorded and later transcribed verbatim for data analysis procedures, such as coding and categorizing.

Content analysis was used to analyze data. This technique was chosen because it employs systematic and objective procedures to interpret the accounts of participants, searching for indicators of what is behind the speech. Through the technique, one can see the similarity of the participants’ statements (Bardin, 2010). Nvivo 10.0 software was used to organize the data collected and conduct content analysis.

The organization of the results was done following two types of analysis categories: (1) A priori – constituted from the reference framework; and (2) A posteriori: developed based on the similarity of participants’ statements. So, e created a new category in which most of the participants said something similar to others about the topic of this study (topic 5.4). The results are described and discussed in the following sections, in which the postulates of this research on the topic are presented.

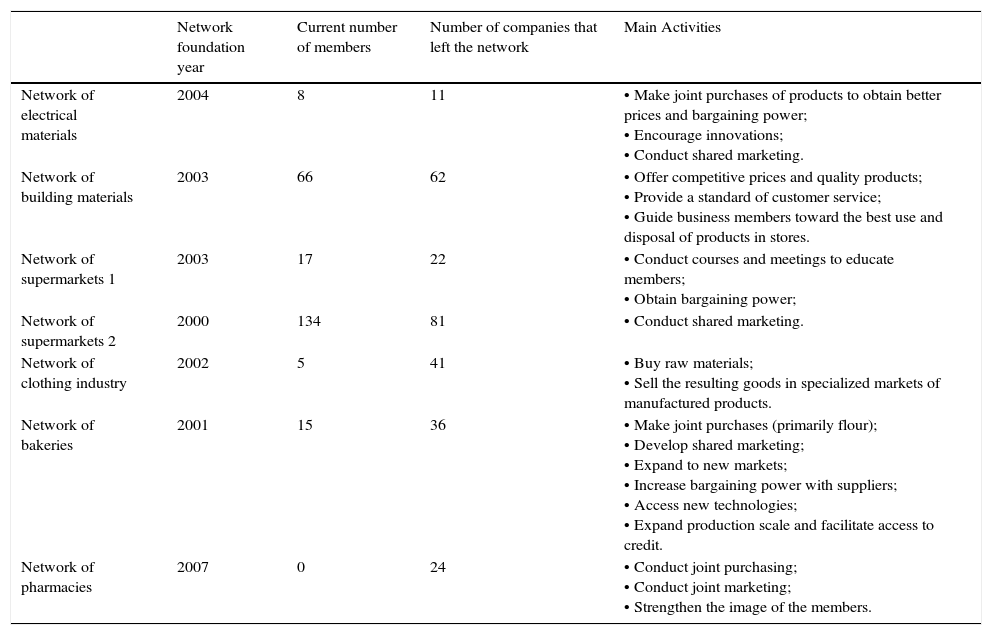

Brief description of the networks studiedThe networks chosen for this research concerned different business sectors. As previously explained, they were chosen intentionally to cover more than one field of activity to allow the identification of general reasons that cause organizations to withdraw from the networks. To provide an idea about the networks mentioned in Topic 3 (above), we developed a table with the main characteristics and activities of each of these networks (Table 2).

Characteristics of the surveyed networks.

| Network foundation year | Current number of members | Number of companies that left the network | Main Activities | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Network of electrical materials | 2004 | 8 | 11 | • Make joint purchases of products to obtain better prices and bargaining power; • Encourage innovations; • Conduct shared marketing. |

| Network of building materials | 2003 | 66 | 62 | • Offer competitive prices and quality products; • Provide a standard of customer service; • Guide business members toward the best use and disposal of products in stores. |

| Network of supermarkets 1 | 2003 | 17 | 22 | • Conduct courses and meetings to educate members; • Obtain bargaining power; |

| Network of supermarkets 2 | 2000 | 134 | 81 | • Conduct shared marketing. |

| Network of clothing industry | 2002 | 5 | 41 | • Buy raw materials; • Sell the resulting goods in specialized markets of manufactured products. |

| Network of bakeries | 2001 | 15 | 36 | • Make joint purchases (primarily flour); • Develop shared marketing; • Expand to new markets; • Increase bargaining power with suppliers; • Access new technologies; • Expand production scale and facilitate access to credit. |

| Network of pharmacies | 2007 | 0 | 24 | • Conduct joint purchasing; • Conduct joint marketing; • Strengthen the image of the members. |

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

As shown in Fig. 2, the main objectives of the selected networks are to conduct joint purchasing to obtain more competitive prices, to exchange information among members, to conduct joint marketing, and to strengthen the image of their members. The differences among these networks are mainly the fields of activity of each network and the number of members that left and those that still remained in the networks. It is important to highlight that the network of pharmacies was the only one that we studied that had ended its activities because all of its members withdrew from the network. This particular network failed in 2008, and it operated for only 10 months.

ResultsInitial contact and network formationThe decision of the manager of a company to enter into a partnership with other companies may be influenced by the difficulty of finding partners. Chen (2010) mentioned that the formation of relationships based only on the availability of partners, without the observation of what this partner can contribute and without selection criteria, is negatively related to good perceived results. Certain common characteristics of network members promote reliability in the relationship and make collaboration among them easier (Chile & Mcmackin, 1996; Ostrom, 1990).

Graddy and Chen (2006) found that although organizations were willing to comply with the funding requirements to form a network, they were limited by their potential capacity. Accordingly, Hitt, Levitas, Arregle, and Borza (2000) suggested the selection of partners as a determining factor for the success of organizational collaborations, as is the case of an interorganizational network, due to the need to align specific resources that allow the continuity of exchange between members.

In the selected networks, participants (both presidents and business owners who left the networks) suggested that the lack of criteria for member selection was a problem during the formation of the networks. Organizations were invited to join the networks without due attention to the selection criteria. Due to this issue, some organizations left the networks because of a conflict of interest or other problems that could have been identified earlier, during the formation of the network. Transcript excerpts of NP2 and BO6 highlight this lack of selection criteria: Look, I just know that we received the invitation to participate. [The network invited] … people, companies, and they accepted. If they had an interest in participating they could join the network, and then by word of mouth the network was growing. We had no criteria. (NP2) I do not know if there are [criteria], I don’t think so. They had big, small [companies]. There was nothing there [selection criteria]. (BO6)

It can be observed by these statements that the goal at that moment (of the formation of the network) seemed to be simply to form the network. Apparently, the lack of clear criteria for the selection of members of a network is not directly related to the withdrawing of members; however, failure to comply with this aspect creates difficulties with network coordination, alignment of goals, and the expectations of each partner.

Networks with no criteria for selecting members may have problems later in the relationship. Members may conflict about the objectives of the network, the fulfillment of agreements, and the accomplishment of contracts established in the network. Many companies join networks without having sufficient potential or appropriate conditions that allow them to comply with, for example, a purchasing goal established by the network. This fact can generate other problems in the network, such as a lower level of trust with suppliers and among network members.

According to Fig. 1, it is relevant to highlight that social ties and legitimacy were not identified as aspects that influence organizations’ decision to withdraw from interorganizational networks. Network presidents and the majority of business owners mentioned that an own network brand increases the legitimacy of the companies and does not influence the withdrawal of network members. However, owners of companies which have operated in the market for several years expressed some disagreement. One business owner mentioned that there was an apparent image conflict between networks and well-known, traditional companies in the cities in which they were founded. In an interview, one of the business owners said that when he changed the facade (storefront) of the store, many customers questioned whether he would sell the company or change anything in the store. Therefore, it seems that the orientation of the networks to change and standardize facades and other procedures of member companies should be cautiously and properly oriented to avoid creating member conflict and discontent.

Network developmentIn a cooperative network, management activities are the result of a negotiation process among leaders of the companies participating in the interorganizational relationship (Wegner & Padula, 2010). The management of one network involves a system of rules created by the group indicating how decisions were made. Participants mentioned that all the important decisions and those that could affect the partners were made by the large group within the system of rules created by the network. According to network presidents, this issue did not interfere with the withdrawal of members from the networks. The following transcript excerpt of NP3 alludes to this issue: So, before I could set a goal to a supplier, for example, I would have to present it at the committee meeting to see if the committee agreed. Then I would get ready to say whether or not we accept the goal, and then pass this onto the supplier. (NP3)

However, this is not the view expressed by the business owners who were interviewed. They argued that many decisions in the network were taken individually by network presidents, without considering the conditions and the system originally proposed. The following transcript excerpt from BO6 exemplifies this issue: In the network, they [network presidents] made agreements and business [arrangements] which were good for them, but here [in our region], it was not good for us. Here we are more rural. We have another type of customer who has other needs. It is different. (BO6)

In view of this statement, it is possible to verify that the management and decision-making process in some of the selected networks – as perceived by the interviewed business owners – was centered in the network presidents, generating a great deal of dissatisfaction. Based on the interviews, it was found that many decisions, particularly which goods were to be purchased together, were imposed by the network management board as a target because it would benefit them. In this respect, network managers should give special attention to generating alternatives and providing flexibility to members in performing joint activities. This would enable each company to better meet the needs and demands that are peculiar to different cities and regions in which the network operates, even if the network operates under a standardization perspective. Provan and Kenis (2007) discussed that in some evolved network structures (like NAO – Network Administrative Organization), managers begin to establish certain control mechanisms and standards of conduct to ensure the established agreements and business arrangements. Network standardization is crucial as the network evolves, since the network becomes recognized by this standard. However, we discuss that a horizontal network that comprises a large regional area needs to have certain flexibility to meet the peculiarities of companies in each coverage area.

A low level of exchanging resources, which refer to skills, complementary abilities, and exchange of information about new technologies or markets, was also analyzed as a possible reason for companies to withdraw from networks (see Fig. 1). However, neither group interviewed in this research referred to this aspect as a problem. Therefore, this issue was not further analyzed in this work.

One factor cited by participants from both groups as a determinant for members leaving networks was lack of trust. Trust influences the management of the network, the honesty and transparency in meetings among members, the implementation of a joint project or activity, the strengthening of negotiations with suppliers, and helps to reduce information asymmetry and opportunism. According to Bachmann, Knights, and Sydow (2001), without a minimum level of trust, it is almost impossible to establish and maintain successful organizational relationships over time. Lack of trust was considered a problem by most participants, an issue that is confirmed by the statements of NP4 and BO10: Yes, the lack of trust was an issue. Because of this, without the trust of the members, it is not possible to work. It's just that I don’t work with whom I cannot trust. The person has to be reliable. He has to be someone with whom I can confide data and vice versa. This is trust that [there] will not be any foul play. But, if your question was, whether this influenced the decision of organizations to leave? Yes, it did. (NP4) Lack of trust was also a problem. […] I was classified only as a member and so I could not monitor them [network management] and work with them. The lack of trust was a problem. (BO10)

From these transcript excerpts, it is clear that certain attitudes from some network managers and members generated suspicion and fear in relation to the implementation of new activities in the network because they increased members’ distrust. The asymmetry of information and the lack of clarity in negotiations and information were other problems cited by some participants and which resulted in a lack of trust. This corroborates the statement by Sadowski and Duysters (2008) that the failure of a strategic alliance has its origin in a mismanaged partnership, in which there is no trust among the partners involved.

Along with trust, commitment was cited as one of the most important factors for the formation and development of interorganizational relationships. Without commitment, difficulties arise with regard to negotiation and reciprocity among members. It is also important concerning individual obligations, such as participation in meetings, compliance with agreements, and other joint activities.

A lack of commitment may lead many companies to become discouraged or abandon cooperation because they feel they are working for others. The participants’ statements verify that the lack of commitment from some members was a problem and was related to the fact that some members abandoned the relationship. The following transcript excerpt from NP1 illustrates this aspect: A major problem in our network is indeed the question of commitment. You define who is responsible for the expansion, you define the structure of the network and what needs to be done, but this just does not happen. If the president does not lead the way, and sometimes even by doing so, people always have an excuse. They have time to play football, but to come to a board meeting, to visit a future associate, they do not have time. (NP1)

Similar to network presidents, some business owners also stated that the lack of commitment of many members was a problem for the network. Some business owners who left the networks even admitted their own omission and lack of commitment to the network, as observed below in an excerpt from BO3: The main factor was that I did not participate in network joint activities. I ended up not committing to the network. I was involved in other activities and ended up not participating in the activities of the network. I think that in everything that we do not participate [in], there is no way to keep up... For me, a guy who comes into the network, he has to be aware that he will have to change, and I could not adjust to that. (BO3)

A lack of commitment creates difficulties in discussing issues and making decisions with all of the members in meetings, as well as in executing joint activities. As highlighted by Castro, Bulgacov, and Hoffmann (2011), commitment is reflected in the loyalty and effort of partners to maintain a relationship, which outlines the continuation and strengthening of the network. Without the partners’ commitment, difficulties arise with the implementation of activities, improvements, and gains in the network.

Another issue in the cooperative process is related to the opportunism of one or more members of the network. This aspect involves information asymmetry and the breaking of agreements, standards, and principles that guide the network. The opportunistic attitude is usually motivated by the possibility of gains in a shorter period, or even immediately, at the expense of future earnings. Opportunism affects the confidence of the group, increases the difficulty in managing and coordinating joint activities, and generates uncertainty in the network. As NP3 explains below, it is possible to confirm the existence of opportunistic situations in some of these networks: Some people left because they were opportunistic. A situation, for example, that I can mention was when an associate trusted another associate to visit his business and find out things he did not know. He went there and went through everything. He visited the company when the manager was not there, only the employees, and took advantage of this partnership to see things that he thought he could see. Trust was broken. (NP3)

This statement exemplifies the common opinion of presidents that were interviewed in this research. Conversely, the business owners interviewed referred to the opportunistic behavior and attitudes of some partners, but especially from the board, as stated below by BO6: Opportunism? Oh, [yes] there was. Sometimes, by buying in large quantities, they didn’t distribute the goods and other times it was a good deal for them, and it wasn’t for us. We witnessed things like this. (BO6)

Another aspect investigated in this research was the cost to maintain the network, which was a critical issue cited by the participants. Generally, a company remains in the network if the costs are lower than the gains it obtains by staying in the network; that is, if the cost–benefit ratio is positive. The statements of presidents and business owners show that the reason for some network members to abandon the cooperation process was the high cost of being in the network, and also because the members could not visualize gains that would offset these costs. The transcript excerpts from NP1 and BO2 below demonstrate this situation: Business owners left because they didn’t see [an] advantage in being part of the network. They had to pay a monthly fee. As they sometimes did not have substantial purchases and because we are a small network, we couldn’t negotiate considerable discounts. So, they made a calculation: ‘oh, I’m paying this much and I’m gaining this much’; and then thought that it was not worth remaining in the network. Then people ended up being discouraged. [...] Hence, things were not evolving. They ended up not wanting to stay in the network and asked to leave. (NP1) Cost was one of the factors that made us leave. We started like this: we had no advantage because we were already a well-known store here in this town and we had a good reputation with suppliers as well, but the network did not bring in new suppliers. We just spent a lot. Every month we had to pay, let's say, one or two wages, and we got no return. (BO2)

The excerpts above corroborate the postulates of Park and Ungson (2001, p. 47), who claimed that “a network is able to sustain its structure and remain an efficient mechanism for intercompany transactions while the economic benefits of the partners overlap the potential costs of managing the alliance.”

Finally, an aspect mentioned only by business owners was the existence of asymmetric incentives to invest in the relationship, which is a factor emphasized by Khanna et al. (1998) as a reason for the discontent of many companies with the networks in which they are inserted. The following transcript excerpt from BO6 exemplifies a situation regarding this aspect: There were some cases, such as advertisements on television. They were broadcast in certain places, such as in Cruz Alta and region, but here these advertisements were not transmitted [on television]. The cost of this activity was included in the network costs and so I was paying for something that I did not benefit from. (BO6)

In this study, it was found that many companies did not receive returns on their investment, and they became discouraged from continuing to invest in a joint activity or joint action. The cooperation then weakens and becomes a reason for the withdrawal of companies from the collaboration process due to results being inconsistent with contributions.

Network consolidationIn this section, four aspects of perceived effectiveness of the collaboration were analyzed. The first one was the reduction of autonomy of the companies in the network. Comparing the transcripts of both network presidents and business owners, it could be seen that the reduction in autonomy of member companies was not an aspect mentioned by the presidents. However, this aspect was mentioned by some business owners and was negatively evaluated; business owners who mentioned it argued that that the purchase of goods became restricted to suppliers who associated with the network. These issues are highlighted in the following transcript excerpt from BO8: The network imposes the purchase of a certain product that […] is well known in a determined region, but that people are not familiar with here. It is the same thing as if I were to sell a Northeastern product in my shop here in the South. It will never sell. (BO8)

The reduction of the autonomy of companies generated a problem for the network and for its members. On the one hand, the network pressed members to purchase from a specific supplier to gain greater bargaining power and price reductions by buying in bulk. On the other hand, the member had a long-established partnership with a certain supplier that offered him better buying conditions. This type of policy generates conflicts between the interests of the network as a whole and some of its members.

Among the aspects that were analyzed in this sub-topic, only one (the shortfall in achieving networks’ goals and objectives) was mentioned by participants of both groups as a factor that influences companies’ decision to leave networks. Concerning the achievement of goals, Wegner and Padula (2010, p. 74) stated that “the continuity of cooperation is conditional on the ability to achieve the proposed goals and make members more competitive.” In this study, the statements of some participants specifically show that the objectives initially proposed during the formation of the network were not being achieved. The dissatisfaction of some partners due to not achieving goals and benefits began to incite them to leave the networks. The following transcript excerpts from NP1 and BO6 illustrate this point: Yes, it happened. The initial idea for the formatting of the network was one thing, and then another thing happened. […] Everyone thought they would make a lot of money fast. And a network of cooperation is something you have to commit yourself to in order to make money in the medium and long term, but it takes the cooperation of everyone involved. (NP1) I think that the [original] purpose of the network, of forming a purchasing group, was not achieved. I did not see one thing that could add value to my business and to others’ [businesses]. […] It was not possible to meet the expectations of small business owners who were members, you know? (BO4)

There are two situations to analyze based on the statements above. The first one is related to failure in the formulation of goals when the network was being formed. At that time, certain goals (that the network could not achieve) were apparently proposed only to attract a greater number of companies and to form the network. This is consistent with studies by Pereira, Venturini, Wegner, and Braga (2010), who stated that conflicts are caused by organizational objectives not being achieved by a member of the network. It is worth noting the fact that a negative assessment regarding the achievement of objectives is ultimately a consequence of all the other aspects discussed so far.

The other two aspects shown in Fig. 1 – the lack of interorganizational learning and the lack of innovation and value creation – were not perceived by participants as problems that are directly related to the objective of this study.

Individualistic profile of members and immediacy for resultsThe management and organization of networks require structuring processes and management practices that enable the achievement of goals and meet members’ expectations. However, business owners often want to see results immediately and do not understand that a certain period of time is needed for the consolidation of the group. Wegner and Padula (2012) also highlighted that immediacy of results is one of the problems faced by interorganizational networks, and that this problem is related to both the withdrawal of members from networks and to the failure of some networks.

In transcript excerpts, it was found that the immediacy for results is a problem for networks and that it is related to the withdrawal of members. This can be seen in the following transcript excerpt from NP7: Well, in our case, the network was almost not formed because of the issue of immediacy. In the formation of the network, we almost drove the consultant crazy because of the results. We asked him all the time: ‘when will we earn anything’ [...]. During the formation of the network, members have to have patience, because in case they don’t, there is no network. And, if they are thinking about forming a network and that in 30 days, they will be buying or doing something together, it will be complicated. The business is bound not to evolve and whoever wants immediate results is going to withdraw. (NP7)

There was a conflict when comparing the interviews of the presidents and business owners. Among the business owners that withdrew from the networks, it was found that none of them referred to a desire for immediate results as one of the aspects that could be a reason for leaving the network. Perhaps they did not wish to admit it, but according to the presidents, the desire for immediate results is a problem in interorganizational networks.

Another negative aspect for the coordination and management of networks refers to the traditional, individualistic attitude of some network members. Many members, in spite of being part of interorganizational networks, present individualistic profiles and defend their individual interests over collective interests. In the collective opinion of participants of both groups, individualism was regarded as restrictive to the permanence of companies in the networks. This is exemplified by the following transcript excerpts from NP6 and BO4: Individualism cannot exist within the network. In the network, the keyword is ‘we’. We are going to do, we will build, we will have goals, we can, we will, the network will do, we will make the decision. In a group, if you think individualistically, it will not work for sure. (NP6) Individualism was quite visible. That's a good word. The person who was going to make the purchases did not care about other [members’] businesses. He made the purchases of whatever [products] were good for him. His pharmacy was selling those products well, but other pharmacies were not. This is individualism. (BO4)

Due to the existing individualism of some members in the network, as shown above, members reduced the number of joint activities or even abandoned them. Thus, they ended up losing opportunities to gain advantages for the group and decreasing the potential benefits that the network could create. This had an influence on the negative evaluation of the costs of the network and the decision to leave the network.

It can be seen interviews that members should consider collective gains to be part of a network. Companies that think individualistically within the network become isolated and do not see great advantages for their company, and therefore decide to leave the network. It is noteworthy that joining a network is a challenge; to have substantial gains from this type of association, an individualistic vision must be overcome and replaced by a collectivist vision that involves a collaborative relationship with other companies and joint participation in decision making and the pursuit of common goals.

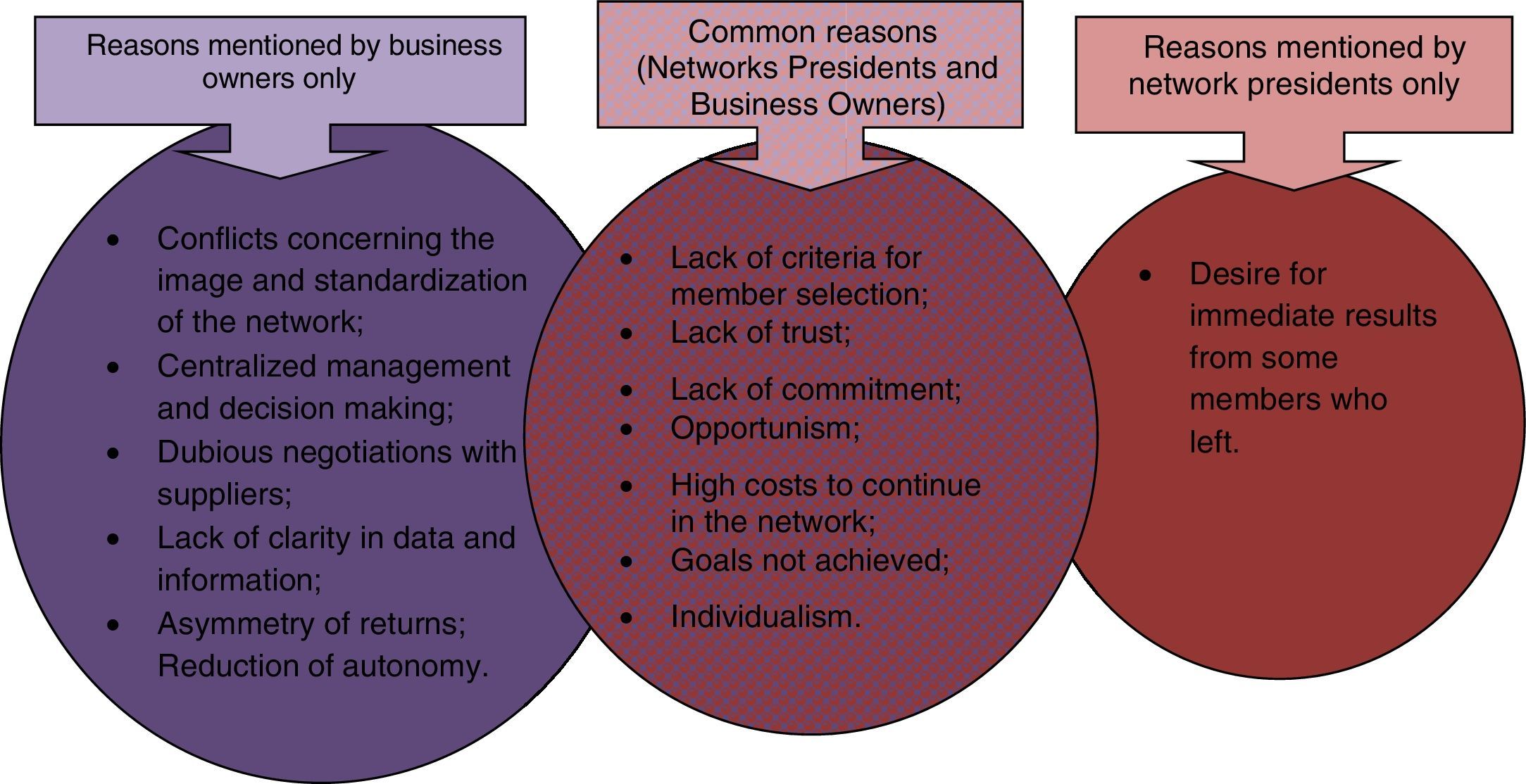

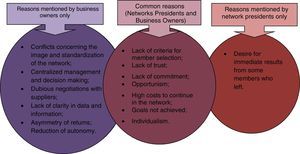

Discussion of resultsAs mentioned by Wegner and Padula (2012), the success or failure of a complex organization such as a network of companies cannot be attributed to isolated factors without risking oversimplification. In this sense, Fig. 2 seeks to organize and provide a clear view of the reasons mentioned by the business owners and compare them to those cited by the network presidents.

Fig. 2 presents some aspects mentioned by both groups of participants (network presidents and owners of companies that left the network). One aspect refers to the lack of criteria for the selection of members during the formation of the network and, during its development and consolidation, when a new business owner decides to join the network. As Galbraith (1998) and Easton (1997) noted, the selection of members is related to the formation of interorganizational networks with regard primarily to the strategy, the structure, and the decisions about the objectives for the formation of a joint undertaking. Selecting members without criteria will result in conflicts of interest and difficulties in adding value to the network, which will lead to consequent dissatisfaction of members and their withdrawal from the network. Furthermore, it will not facilitate resource interaction, as proposed by Baraldi, Gressetvold, and Harrison (2012).

Another common aspect mentioned by both groups of participants was the lack of trust. However, we highlight an apparent difference in the factors that lead to this lack of trust: while network presidents considered lack of trust to be related to the fear of members in exchanging information, disseminating knowledge, and being honest and transparent in meetings and building an environment of partnership, business owners attributed it to dubious negotiations with network suppliers and the lack of clarity and transparency of data and information passed on by the network board.

This lack of trust in both groups goes against the statement by Taticchi, Cagnazzo, Beach, and Barber (2012), who explained that trust will make members more willing to take risks and provide certain strategic and operational freedom for the network to develop valuable activities, enabling the creation of a long-term developing environment. The absence of trust is indirectly related to failure in achieving the goals proposed by the network and to the negative ratio between costs and advantages of being part of the network, factors that were also mentioned as problems by participants.

Lack of commitment was also an aspect that was emphasized by both groups, who mentioned that some activities developed by the network were not successfully performed because some members did not commit to them. The interviews highlighted that in order to obtain bargaining power and economies of scale, for example, all members must commit and cooperate with one another. However, this did not happen in some negotiations attempted by the network, as shown previously. This corroborates the statement by Pesämaa and Hair (2008) that the success of cooperative relationships is influenced by interorganizational commitment, which is an intrinsic network goal. For these authors, commitment means that a company works for the success of all the companies and vice versa. Thus, commitment seems to be related to perspectives and objectives stipulated by the whole network; if they are not suitable for a member, this member will not commit and will probably withdraw from the network.

Two other common aspects were individualism and opportunism of some network members. Statements from some participants revealed certain opportunistic attitudes and behaviors of some members. The presidents provided example situations in which members broke contracts and joint agreements because of a specific opportunity outside of the network, seeking to obtain immediate gains. On the other hand, members exposed occasions in which partners displayed individualism and opportunism, but highlighted the individualistic thinking and behavior of the network board in making decisions and purchases of goods to benefit themselves. These two problems corroborate the statement by Edelman, Bresnan, Newell, Scarbrugh, and Swan (2004), who explained that opportunistic attitudes are usually motivated by the possibility of gains in a shorter term, or even immediately, to the detriment of future earnings. Indirectly, this situation negatively affects trust and increases the difficulty in managing and coordinating network activities.

All of these aspects directly or indirectly influenced the realization of the proposed goals and the balance between the costs of being part of a network and the benefits obtained from it. These two factors were also mentioned by both groups. Failure to achieve objectives proposed by the network – thus leading to negative assessments of the cost–benefit balance – is an aspect that influenced members to leave the network.

Thus far we have shown aspects mentioned by both groups of participants. However, Fig. 2 shows that one aspect was mentioned only by network presidents: the desire for immediate results. As we will expose in the last section of the paper, presidents stated that this aspect was a problem in the networks. Perhaps many network members abandoned cooperation because they did not attain returns from the network. However, they most likely did not understand nor had any patience with the fact that gains are obtained only in the medium and long term in some networks. This corroborates the statement by Wegner and Padula (2010) that the desire for immediate results is one of the problems that affect the continuity of networks, and is a problem that is related to the withdrawal of members and failure of business networks.

Conversely, there were some aspects mentioned only by members who withdrew from cooperation. The first aspect refers to conflicts due to the standardization of network images and storefronts. As stated earlier, some companies felt they lost some of their traditional image by changing the storefront and other internal arrangements as suggested by the network.

The second aspect concerns the lack of clarity in data and information passed on by the network board. This affects the level of trust the members have toward the network and the effectiveness of other joint activities. This aspect can be intrinsically related to asymmetry of information, which generates gains for those who have privileged information and do not allow other agents to monitor the activities that are performed (Byrns & Stone, 1996).

The third aspect reported by some members is the asymmetry of returns, which refers to investments from which some business owners receive no benefit; for example, from marketing campaigns in other cities and television ads in other regions.

The fourth aspect is the reduction of autonomy of the companies in the network. This view of some members is due to the need to reduce the time available for their own activities and to limit continuing negotiations with traditional suppliers.

Another aspect that have to be highlighted is the power struggle in the network. Indirectly, if we analyze several statements made by business owners whose companies left the network, we may intrinsically note that they are related to power or lack thereof. Network presidents want to preserve their interest, and will form groups to attain power to align network proposals and objectives to their advantage. They may forge coalitions with members sharing similar views, while companies that are not satisfied with network objectives and results and probably belong to a small group in the network have no power to change network behavior in a way that is more consistent with their interests. Consequently, they will possibly withdraw from the network.

In essence, these problems shown so far by both groups of participants are related to and ultimately influence the withdrawing of members from the network. Therefore, they cannot be attributed to isolated aspects. A complex agglomeration of factors – which causes the management of networks to be a great challenge – is behind the withdrawal of members from the network.

Final considerationsThis paper addresses an unexplored issue in interorganizational cooperation studies: aspects that influence companies to leave networks. Partnerships take form in an attempt to reduce the vulnerability of companies that recognize their limitations in acting alone. However, it can be observed in the literature on this topic, in both economic and social paradigms, that relevant aspects such as member selection, commitment, trust, decision making, and investments made by members are related to the formation and development of networks. These factors, among others found in this article, when not properly analyzed and managed, provide difficulties for the network's management and influence the continuity of companies in the network.

The overall objective of this research was to identify the reasons that lead companies to withdraw from networks based on the views of network presidents and of business owners whose companies left these networks. The contribution of this work offers an understanding of collaborative relationships and the formation, development, and consolidation of networks by highlighting problems and conflict points that must be managed.

By analyzing the results of this research, it is possible to identify some common problems stated by the two groups of participants, such as lack of criteria for member selection, lack of trust, lack of commitment, and opportunism and individualism of some members. All of these factors limit the potential to add to the value of the network and obtain higher possibilities of competitive advantage for members; they also indirectly reflect on two other problems mentioned by presidents and business owners: a negative cost–benefit balance and failure to achieve proposed goals and objectives.

Among the results of this research, we highlight aspects that were only mentioned by the business owners: conflicts over the standardization of network images and storefronts, dubious negotiations with suppliers, lack of clarity in data and information, asymmetry of returns, and reduced autonomy of some companies. These aspects may lead us again to the discussion of power and conflict in the network. Different interests of members in the network and consequently a power struggle among them seem to be inherent to these factors. The group that directs and manages the network makes decisions that will invariably meet their own interests, but that may not meet the interests of the entire network, thus creating conflict and dissatisfaction.

We also highlight an aspect that was only mentioned by the interviewed presidents: the desire for immediate results. This last aspect relates to the expectations of business owners when they join a network hoping for immediate gains.

All these aspects may influence the empirical fact that some networks need to address: the withdrawing of members. However, we note that this study does not seek to be normative in the sense of categorically indicating aspects that lead companies to leave networks. Other specific aspects can be related to each network that suffers from this phenomenon.

The study of this topic raises some questions, such as: Is the apparent lack of criteria for member selection a factor that influenced other negative aspects in the networks? What are the expectations of companies when they join a network? To what extent are companies willing to invest in the network? Are companies that leave the network those that have a more negative view or only those that are less prone to inertia? Studies that advance these issues should be developed to increase understanding on this topic and increase the chances of success for such undertakings, particularly those formed by small businesses, which typically have greater difficulties in managing their activities.

Concerning study limitations, we noticed that some specific problems that occur in particular business sectors were not analyzed. By studying networks of different fields of activities, the capacity to understand how the specific characteristics of each network influence withdrawal decisions is lost. We recognize that specific network characteristics clearly play an important role in shaping the decisions to leave or remain in a network, and this is one of the limitations of this paper. We also understand that despite having chosen more than one business sector, results are specifically related to them. Studies in each field of activity could elucidate other variables and specific aspects of the topic under investigation in this article and contribute to solidifying a theoretical framework for this phenomenon.

The authors thank to Conselho Nacional de Desenvolvimento Científico e Tecnológico (CNPq) and to Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES) for the financial support to conduct the research.