Extra-intestinal manifestations of ulcerative colitis (UC) can involve several organs.1 In cutaneous manifestations, leukocytoclastic vasculitis (LV) is very rare.2 The association between UC and autoimmune pancreatitis (AIP) has been increasingly reported in recent years3 and AIP and sialadenitis have been observed to form part of hyper-IgG4 syndrome.4 However, a three-way association between UC, AIP and sialadenitis has only exceptionally been reported in medical journals.5

We present the clinical case of a patient with severe UC, as well as AIP, sialadenitis and pustular LV, an association not described previously in the literature.

Clinical caseThe patient was a previously healthy 25-year-old woman who presented clinical symptoms of 6 bloody stools daily, associated with rectal tenesmus and abdominal pain that had started 15 days earlier. Colonoscopy revealed continuous involvement of the mucosa–which was inflamed and friable–and geographic ulcers, findings compatible with ulcerative pancolitis. She responded poorly to an initial prescription of mesalazine (4g/day) and oral corticosteroids, and subsequently to intravenous methylprednisolone (0.8mg/kg/day). A decision to induce remission with 5mg/kg infliximab obtained a good clinical response after 48h.

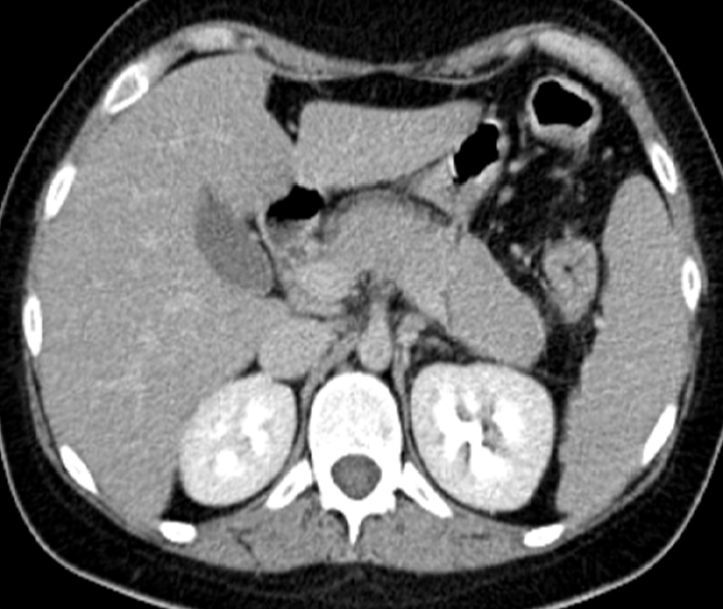

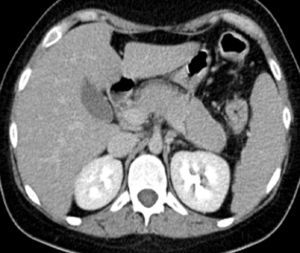

Seventy-two hours after the corticosteroid dose reduction, the patient presented epigastric pain and vomiting. Laboratory tests revealed an amylase level of 237mg/dL (30–310mg/dL) and an abdominal computed tomography (CT) scan showed diffuse enlargement of the pancreas, with homogenous uptake and peripheral hypoechoic halo, consistent with acute pancreatitis of autoimmune aetiology (Fig. 1). The pancreatitis responded rapidly to an increased dose of methylprednisolone (60mg/day). Note that the patient was not taking any medication other than that mentioned above.

Twenty-four hours later, the patient presented fever (39°C), oropharyngeal ulcers, papular skin lesions that progressed to pustules (Fig. 2) and sialadenitis (parotid, sub-maxillary and sub-lingual). Empirical antibiotic and antiviral treatment resulted in an improvement in symptoms within 10 days.

A viral microarray assay was positive for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) in blood and in nasal, oral and pharyngeal exudates, for human herpes virus (HHV)-7 in oral lesions and for HHV-6 in the colon. The remaining serology tests were negative. Anti-nuclear antibodies were negative in the autoimmune study. Serum IgG4 was 0.278g/dL (0.052–1.25g/dL) 6 weeks after the acute episode.

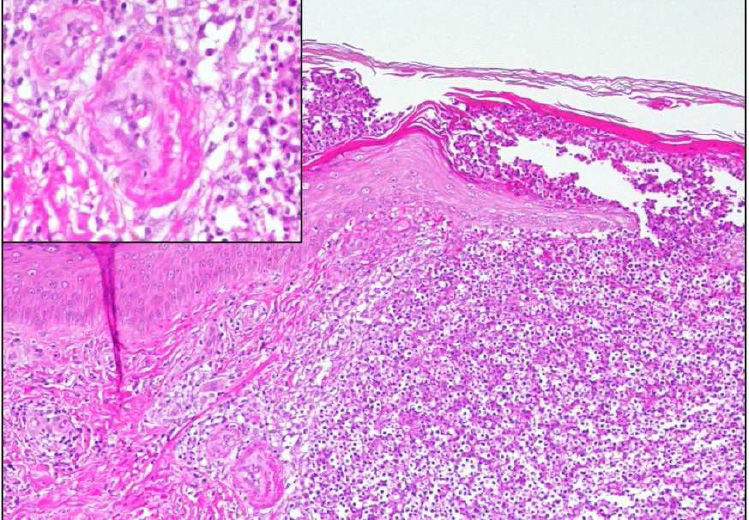

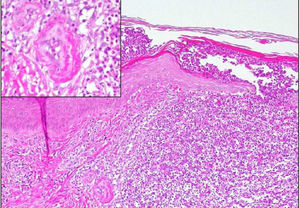

A skin biopsy revealed neutrophilic focal aggregates intraepidermally and on the superficial dermis, with red cell extravasation and images of fibrinoid necrosis in small vascular structures, consistent with pustular LV (Fig. 3).

The patient was discharged with oral methylprednisolone (40mg/day) in a tapered dose (decreasing by 8mg/week) and infliximab. She has remained asymptomatic during follow-up. Abdominal magnetic resonance imaging at 2 months showed resolution of the pancreatic inflammatory abnormalities.

DiscussionThe association between AIP and UC has been increasingly described in recent years.3 AIP is classified into 2 sub-types. Type I or lymphoplasmacytic sclerosing pancreatitis (LPSP), more prevalent in elderly, male and Asian patients, is considered part of an IgG4-related systemic disease. Type II or idiopathic duct-destructive pancreatitis (IDDP), more prevalent in young Caucasian patients, is associated with UC and with normal IgG4 levels. Type I AIP usually presents with obstructive jaundice, while type II presents mainly with abdominal pain.6,7 Pancreatic function in type II, unlike in type I, is generally not altered.8 Finally, type I has a high relapse rate, whereas relapse is rare in type II.9

Different criteria are used to diagnose AIP, although higher sensitivity (95.5%) and precision have been obtained for the International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria (ICDC 2011),10,11 which is based on 5 criteria: pancreatic image, serology, involvement of other organs, histology and response to corticosteroids. According to the ICDC, our patient would meet the criteria for a definitive diagnosis of type I AIP, as she had the typical imaging result and involvement of other organs (sialadenitis); on the other hand, she would also meet the criteria for probable type II AIP, as she had UC and responded well to corticosteroids.

Although sialadenitis is not described as an extra-pancreatic manifestation of UC, it is nonetheless related to type I AIP and forms part of IgG4 syndrome.12 Elevated IgG4 levels were not detected in our patient; however, a false negative result cannot be ruled out, given that the sensitivity of increased IgG4 varies between 57.1% and 73.3% in type I AIP,13 and also considering that, in up to 50% of cases, IgG4 levels can revert to normal following corticosteroid treatment.14

Other possible aetiologies of sialadenitis are infections, inflammation and adverse reactions to iodine-containing contrast media.15 Viral aetiologies include EBV, which is very prevalent in the population, so a positive result in the microarray study would need confirmation by polymerase chain reaction (PCR) to rule out possible reactivation.16 EBV reactivation has been reported in patients treated with etanercept (3.9%) and adalimumab (4.6%) but not in patients treated with infliximab.17

LV is a rare skin manifestation of UC, with a clinical spectrum ranging from palpable purpuric lesions to vesicles, pustules or ulcers. Histologically it is characterised by neutrophilic infiltration and nuclear remnants in post-capillary venules.3,18 While the association between LV and the other entities described in our patient suggests a likely autoimmune origin, another reported cause of LV is the use of infliximab,19 although our patient continued with this treatment without presenting any new episodes.

In conclusion, the association of UC, AIP, sialadenitis and pustular LV has not been previously reported in the literature. There may be aetiological doubts about some of the clinical symptoms in this case and no histological studies of the pancreas or salivary glands were performed, but an autoimmune origin seems to be the most likely aetiology in our patient.

Please cite this article as: Lindo Ricce M, Martín Domínguez V, Real Y, González Moreno L, Martínez Mera C, Aragües Montañes M, et al. Colitis ulcerosa asociada a pancreatitis autoinmune, sialoadenitis y vasculitis leucocitoclástica. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:214–216.