The Spanish Society of Digestive Pathology (SEPD), the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver (AEEH), the Spanish Society of Infections and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) and its Viral Hepatitis Study Group (GEHEP), and with the endorsement of the Alliance for the Elimination of Viral Hepatitis in Spain (AEHVE), have agreed on a document to carry out a comprehensive diagnosis of viral hepatitis (B, C and D), from a single blood sample; that is, a comprehensive diagnosis, in the hospital and/or at the point of care of the patient. We propose an algorithm, so that the positive result in a viral hepatitis serology (B, C and D), as well as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), would trigger the analysis of the rest of the virus, including the viral load when necessary, in the same blood draw. In addition, we make two additional recommendations.

First, the need to rule out a previous hepatitis A virus (VHA) infection, to proceed with its vaccination in cases where IgG-type studies against this virus are negative and the vaccine is indicated. Second, the determination of the HIV serology. Finally, in case of a positive result for any of the viruses analyzed, there must be an automated alerts and initiate epidemiological monitoring.

La Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva (SEPD), la Asociación Española para el Estudio del Hígado (AEEH), la Sociedad Española de Infecciones y Microbiología Clínica (SEIMC) y su Grupo de Estudio de Hepatitis Víricas (GEHEP), y con el aval de la Alianza para la Eliminación de las Hepatitis Víricas en España (AEHVE), han consensuado un documento para realizar un diagnóstico integral de las hepatitis virales (B, C y D), a partir de una única extracción analítica; es decir diagnóstico integral, en el centro hospitalario y/o en el punto de atención del paciente. Proponemos un algoritmo, de manera que el resultado positivo en serología frente a los virus de las hepatitis (B, C y D), así como el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (VIH), activaría el análisis del resto de virus, incluyendo la carga viral cuando sea preciso, a partir de la misma extracción sanguínea. Además, hacemos dos recomendaciones adicionales. Por un lado, la necesidad de descartar una infección previa por el virus de la hepatitis A (VHA), para proceder a la vacunación en los casos en que los anticuerpos de tipo IgG frente a este virus sean negativos y la vacuna esté indicada. Y, por otro lado, la determinación de la serología del VIH. En caso de un resultado positivo para cualquiera de los virus analizados se deben emitir alertas automatizadas y activar la monitorización epidemiológica.

Viral hepatitis caused by hepatitis B, C and D viruses (HBV, HCV and HDV) represents a significant threat to public health due to its high morbidity, mortality and transmissibility. It is estimated that there are around 354 million people with chronic hepatitis B or C in the world (296 million with hepatitis B and 58 million with hepatitis C),1 and 5% of those with HBV infection have HDV infection.1,2 Global mortality attributable to viral hepatitis stands at 1.4 million deaths each year, with chronic hepatitis B and C being the most significant.3 In Spain, the prevalence of surface antigen (HBsAg) (0.6%) and antibodies against hepatitis B core antigen (anti-HBc) (8.2%) has not changed in recent years,4 while the latest published figures on hepatitis C present data showing lower seroprevalence (1–1.4%) and viraemic infection (0.2–0.3%) than in previous years.5 These figures increase in populations at risk or who are part of a vulnerable group, such as drug users, prison inmates, men who have sex with men (MSM) and immigrants from countries with high prevalence, as that is where the greatest number of cases are concentrated.6,7 The morbidity and mortality associated with viral hepatitis is linked to the persistence of viral replication with progression from fibrosis to cirrhosis and the development of long-term liver complications. This damage can be aggravated if there is coinfection by different viruses, and even more so by the presence of HDV.8 It is estimated that one in six cases of cirrhosis occurring in patients with HBV are attributable to HDV coinfection.2

Hepatitis B can be prevented by vaccination, which is highly effective, while active disease is treated with nucleos(t)ide analogues, which are effective in controlling viral replication.9–11 Direct-acting antivirals (DAAs) against HCV achieve high rates of sustained viral response (SVR) that result in cure of the infection in most patients.12 Treatment of viral hepatitis prevents the development of cirrhosis, decreases the risk of hepatocellular carcinoma and liver transplantation, and improves survival.9,13–17 In addition, treatment for hepatitis C has proven to be cost-effective, even reducing the social burden of the disease.18–21 A recent study shows a very significant decrease in hospitalisations for HCV cirrhosis since the introduction of DAAs, which could be a marginal cause of admissions in the future.22 Likewise, the treatment helps to control the transmission of the virus, which has been reflected in a significant decrease in the prevalence of infection after the introduction of DAAs in recent years.

In the case of hepatitis D, a drug conditionally approved by the European Medicines Agency (EMA), bulevirtide, manages to normalise alanine aminotransferase (ALT) values and decrease HDV-RNA values by two logs or to undetectable levels in a significant percentage of cases.23

Advances in treatment motivated the World Health Organization (WHO) to establish in 2016 objectives focused on reducing the incidence of hepatitis B and C by 90% and mortality by 65%, in order to achieve its eradication in the year 2030.1 In recent years, most countries have established measures aimed at meeting these objectives, achieving an estimated decrease in infections of 6.8 million compared to 2015.24 In Spain, thanks to the collective efforts to implement targeted actions to, among other things, establish screening strategies and search for patients with unknown infection, it has been possible to diagnose and treat a large number of people, above all with hepatitis C,25 and we are on the path towards its eradication.26 But these efforts have been diminished by the COVID-19 pandemic, which has seriously affected health services, causing most of the health resources, especially microbiology services,27 to be used to mitigate it, damaging the care of patients with other diseases such as viral hepatitis. The closure of health centres and hospitals, together with access restrictions, have caused significant delays in diagnosis and the stagnation of treatment initiation.28–31 In addition, this situation has worsened in vulnerable groups that go to community centres, such as harm reduction centres.32 The stoppage of micro-elimination programmes has generated a sharp drop in diagnoses of 25% in health centres and 56% in community centres.33 These delays will cause late diagnosis of the disease34 with the consequent loss of opportunity for cure in its early phases that would modify its natural history. Recent studies show that the absence of adequate care in patients with hepatitis C as a consequence of the pandemic will cause significant increases in the associated morbidity and mortality and its cost.35,36 Therefore, in order to minimise the impact of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic and remain in line with the eradication objectives, it is necessary to adopt measures that reinforce screening programmes, restore the care cascade for viral hepatitis and allow early treatment.37–40 There is also a need to emphasise and further promote already existing effective measures aimed at diagnostic simplification, such as one-step diagnosis (OSD) and point-of-care (PoC) diagnosis, along with early warning systems in microbiology laboratories, as well as continue with micro-elimination strategies aimed at populations at risk or vulnerable groups.

This document provides a series of recommendations made by expert professionals in the diagnosis and management of viral hepatitis and endorsed by scientific societies, which allow the comprehensive diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis (B, C and D) from a single blood sample. Likewise, other recommendations are established aimed at health professionals, services and programmes, in order to prevent infections, facilitate early diagnosis, guarantee follow-up and access to treatment, as well as the dissemination of information on hepatitis and, finally, facilitate the continuous improvement of health models.

MethodsIn preparing the consensus document, a systematic review of the literature was carried out to collect and synthesise recent evidence on the diagnosis of viral hepatitis (B, C and D). In addition, a search was made in the grey literature, including clinical guidelines, conference summaries, information from regional health systems and official organisations. The review focused on the diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis, diagnosis simplification and PoC diagnosis.

Meanwhile, a scientific committee made up of five experts was created, tasked with preparing a first document based on the bibliographic review, and an expert panel made up of specialists in the digestive system, infectious diseases, internal medicine, hepatology and microbiology was established to discuss and agree on the initial document. A total of 22 experts reviewed the document. The panel of experts, based on the initial document, held a deliberation meeting and several subsequent reviews, and agreed on the recommendations to be included in the final document. These meetings took place during the first quarter of 2022, with the document being reviewed and the final recommendations included in June 2022.

The recommendations included in the consensus were based both on the available scientific evidence and on the opinion of experts, according to their experience, when that information was not available. In addition, the consensus document has been endorsed by the scientific societies involved in the diagnosis and management of viral hepatitis: the AEEH (Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver), the AEHVE (Alliance for the Elimination of Viral Hepatitis in Spain), the GEHEP (Viral Hepatitis Study Group) of the SEIMC (Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology) and the SEPD (Spanish Society of Digestive Pathology).

Justification for the comprehensive diagnosis of viral hepatitisScreening for HBV and HCV infections is mainly based on age and risk factors for acquiring the infection.10–12,41–43 However, there is a diversity of criteria regarding who should be targeted for HDV screening. The clinical guidelines of the AEEH and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) recommend HDV detection in all patients infected with HBV,11,41 while the recommendations of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD), despite its high prevalence, direct their detection only to patients with chronic HBV infection who belong to high-risk groups (migrants from regions with high endemicity of HDV, a history of intravenous drug use or high-risk sexual behaviour, and HCV and HIV coinfection, or with elevated aminotransferases, but low or undetectable HBV DNA).10 In Spain, as in other European countries, the HDV screening rate in patients with chronic HBV infection has decreased in recent decades, despite an upturn in the prevalence of HDV infection, mainly among the migrant population, which currently stands at around 5%.44–47

The evaluation of HCV and HDV infection is initially carried out by detecting antibodies against these viruses and, in the case of HBV, by detecting HBsAg. In the first two, confirmation of active infection requires molecular techniques to detect their RNA. In the case of HBV, the presence of HBsAg is what determines the existence of active infection and the evaluation is completed with viral replication markers, determining the HBe antigen and HBV DNA. Generally, the diagnosis is made independently for each infection, that is, if the subject is positive in any of them, the specialist requests a second test to identify other viral liver infections or other related viruses, requiring the patient to come back for another blood draw.

The high degree of similarity in the epidemiology that exists between these viral infections, given that they share risk groups and routes of transmission, means that the risk of coinfection with HBV, HCV and HDV, and even HIV, in their different combinations is high. Coinfection causes greater liver morbidity and mortality and, in this sense, simplifying the diagnosis of viral hepatitis would be advisable and would be in line with the objectives set. Carrying out a comprehensive diagnosis of viral hepatitis, that is, from a single blood draw, has numerous advantages. It helps to identify new infections and detect coinfections, and is also a healthcare tool to reduce additional costs caused by repeated blood tests and unnecessary visits.48,49 Some studies evaluating comprehensive diagnosis for HBV and HCV show positive results in early detection and diagnosis, in addition to detecting patients coinfected with other viruses such as HIV.48–52 Likewise, given the high risk of contracting chronic viral infections and the low level of health care received by the population at risk or vulnerable groups, carrying out comprehensive diagnosis in community centres has proven to be viable, feasible and effective, managing to minimise the chances of missed tests, optimise its coverage and show positive results in terms of test rates.48,50,51,53,54

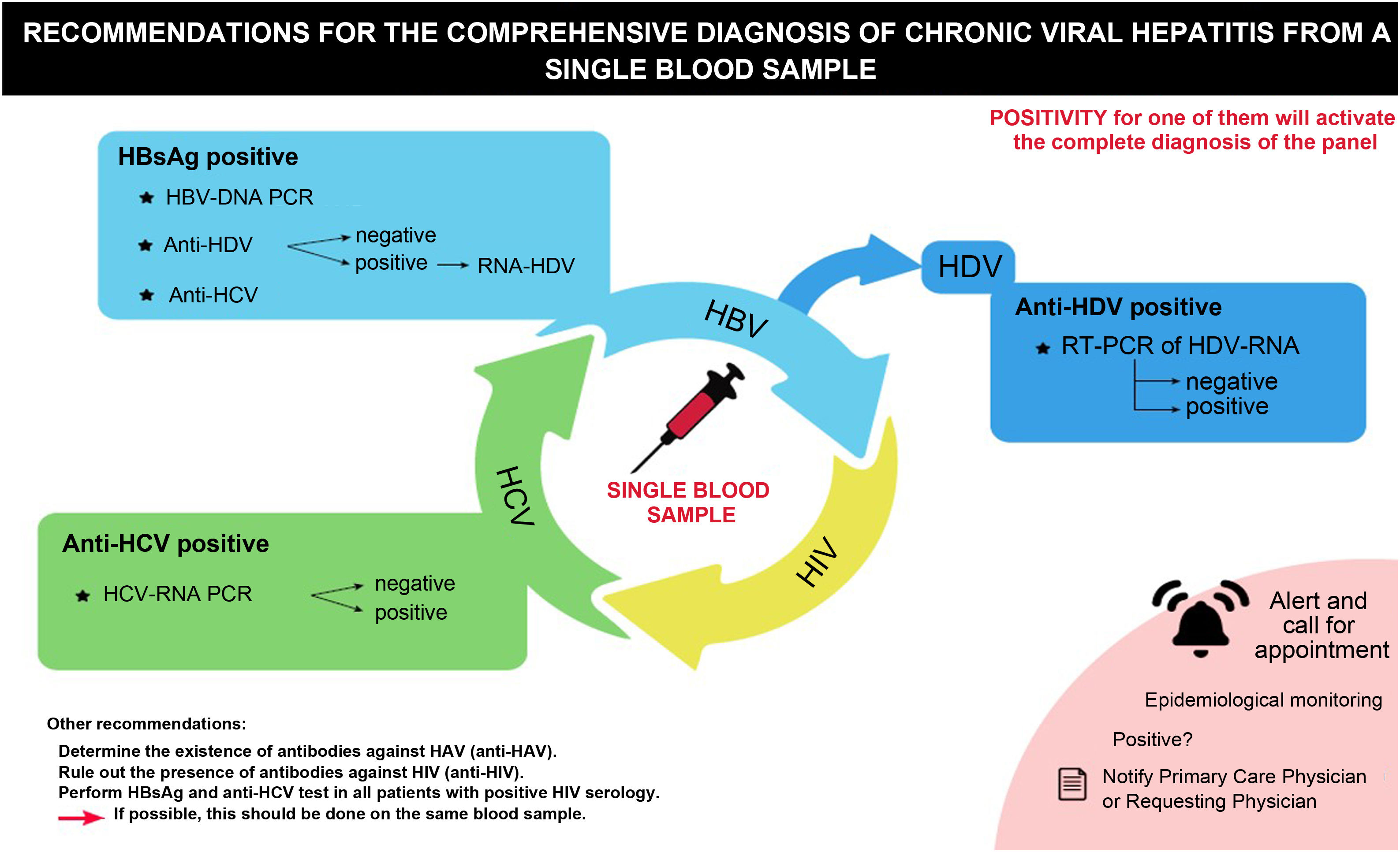

Recommendations for a comprehensive diagnosis of viral hepatitisIn line with the above, a series of recommendations are made aimed at carrying out a comprehensive diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis (B, C and D) (Table 1, Fig. 1).

Key points in the consensus for a comprehensive diagnosis of viral hepatitis from a single blood sample.

| Recommendations for comprehensive diagnosis to be carried out if possible from the same blood sample: |

| a. In all subjects in whom HBsAg is detected, HBV-DNA testing is recommended. In addition, coinfection with HDV and b. HCV should be ruled out by testing for anti-HDV and anti-HCV. |

| c. In all patients who test positive for anti-HDV, HDV-RNA should be determined. |

| d. In all subjects who test positive for anti-HCV for the first time, the presence of HCV-RNA should be determined. In addition, in all anti-HCV positive subjects, HBV infection should be ruled out by testing for HBsAg. |

| Other diagnostic recommendations: |

| a. All HBsAg-positive patients, regardless of HBV-DNA and/or anti-HDV positivity or negativity, as well as all anti-HCV-positive patients in whom HCV-RNA is detected, should be referred for evaluation by a viral hepatitis specialist. |

| b. In those anti-HCV positive patients previously diagnosed and cured, but with risk behaviours, the HCV-RNA viraemia should be repeated periodically. |

| c. In all patients with chronic viral hepatitis (B, C and/or D) the presence of IgG or total antibodies against the hepatitis A virus should be determined. |

| d. HIV infection should be ruled out in all patients with chronic viral hepatitis. |

| e. And, finally, HBsAg and anti-HCV tests should be performed in all patients with positive HIV serology. |

| General measures: |

| a. Simplification of the diagnostic cascade of patients with viral hepatitis and access to treatment. |

| b. Integration of Point-of-Care (PoC) test results and supervision by central microbiology laboratories is recommended. |

| c. Implementation of automated alert systems. |

| d. The creation of automated appointment systems is recommended. |

| a. Implement education, prevention and dissemination programmes. |

DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; HBV: hepatitis B virus; HBsAg: hepatitis B virus S antigen; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HDV: hepatitis delta virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; IgG: immunoglobulin G. RNA: ribonucleic acid.

Recommendations for the comprehensive diagnosis of chronic viral hepatitis from a single blood sample.

DNA: deoxyribonucleic acid; HBsAg: hepatitis B virus S antigen; HCV: hepatitis C virus; HDV: hepatitis delta virus; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; PCR: polymerase chain reaction; RNA: ribonucleic acid; RT-PCR: real-time polymerase chain reaction.

- □

In all subjects in whom HBsAg is detected for the first time, molecular diagnosis of the infection is recommended from the same blood sample, proceeding to the determination of HBV-DNA.

- □

HDV and HCV coinfections should also be ruled out in the same test, by detecting anti-HDV and anti-HCV, respectively.

- □

All patients with positive HBsAg, regardless of the HBV-DNA result (positive or negative) and/or the presence of any marker for the diagnosis of hepatitis C and D (anti-HDV, anti-HCV), should be referred to and evaluated by a viral hepatitis specialist.

- □

In all patients who test positive for anti-HDV, HDV-RNA should be determined using molecular techniques.

- □

In addition, in those HBsAg-positive patients previously diagnosed and with risk behaviours, anti-HDV testing should be repeated periodically.

- □

All patients with hepatitis D should be referred to a viral hepatitis specialist for evaluation and treatment if appropriate.

- □

In all subjects in whom anti-HCV is detected for the first time, the presence of HCV-RNA should be determined, whenever possible, from the same blood sample, using molecular techniques or, if this is not possible, HCV core antigen (HCV-Ag).

- □

In addition, in all anti-HCV positive subjects, HBV infection should be ruled out in the same blood sample by determining HBsAg.

- □

All anti-HCV positive patients in whom HCV-RNA and/or antigenaemia are detected should be referred for evaluation by a viral hepatitis specialist.

- □

In addition, in those anti-HCV positive patients previously diagnosed and cured, but with risk behaviours, the HCV-RNA viraemia should be repeated periodically as recommended by the guidelines to detect reinfections early and avoid transmission.

Patients with chronic viral hepatitis are at increased risk of having other infections such as hepatitis A virus (HAV) or HIV infection, due to common risk factors for exposure.1,55 Coinfection can alter the natural history of each of these viruses and cause an increase in comorbidity and associated mortality.55 Hepatitis A is an acute infection, and people who have it usually recover without treatment. Although in Spain it was an almost non-existent infection, since 2016 there have been significant outbreaks in some regions of the country caused by risky sexual practices among MSM56–59 or among migrants from European Union countries with a low vaccination rate.60,61 Its diagnosis makes it possible to identify people with immunity, that is, those who have had the infection and have antibodies, or on the contrary, those who have not had it and could be candidates for vaccination to avoid infection.10,62 Meanwhile, a considerable number of people with viral hepatitis also have other infections such as HIV. One study showed that HCV and HIV coinfection in patients with chronic HBV occurred in 6.3% and 3.1%, respectively.63 Coinfection is very common, especially in people with a history of exposure or high-risk behaviours such as people who inject drugs, those sentenced to custodial and non-custodial sentences, MSM and sex workers, since they are viruses that share routes of transmission. It is estimated that around 2.3 million people living with HIV worldwide are affected by HCV and 2.7 million by HBV.64 In Spain, HIV/HBV coinfection has remained stable for a decade, standing at 3.2% in 2018, with 26.3% of those coinfected having antibodies against HDV.65 On the other hand, HIV/HCV coinfection has been decreasing in Spain, standing at 2.2% in 2019.66 Clinical guidelines on the management of patients with HIV recommend systematic screening for hepatitis B and C virus infections.67

Integrating the diagnosis of HAV and HIV when performing a test for any other viral hepatitis would help to detect cases of coinfection and would be an opportunity to perform the test in groups with difficulties in seeking health care given its acceptability and feasibility, especially if it is conducted using a rapid test in the centres that they do go to, such as harm reduction centres.68

Recommendations:

- -

In all patients with chronic viral hepatitis (B, C and/or D) the presence of IgG or total antibodies against the hepatitis A virus should be determined.

- -

Likewise, in all patients with chronic viral hepatitis, the existence of HIV infection should be ruled out.

- -

And, finally, HBsAg and anti-HCV tests should be performed in all patients with positive HIV serology.

- -

These tests should be performed, when possible, on the same blood sample used for the rest of the viral markers.

The prevalence of viral hepatitis, specifically hepatitis C, has decreased notably after the adoption of actions aimed at its eradication24 but, there are still underdiagnosed populations, with high prevalence, such as at-risk or vulnerable groups, in whom its detection and subsequent access to treatment remain a challenge.7

The traditional diagnosis of infections in our country requires several visits to the specialist. First, a serology test is performed and, if it is positive, the viral load is analysed, which means a wait between tests that can generate a delay in diagnosis of up to 12 weeks.69 This strategy entails inefficiencies in the management of infections that imply a loss of patient follow-up, representing a significant barrier to elimination. It is necessary to change the approach to viral hepatitis to achieve improvements in the link with health care and reduce the delay in access to treatment.70 Strategies focused on diagnostic simplification such as OSD, that is, determination of antibodies against HCV and, in case they are positive, determination of HCV-RNA in the same sample, are endorsed by scientific societies and national and international organisations71 and have shown their efficiency in screening, particularly in hepatitis.72–75 Compared with traditional methods, OSD increases diagnostic effectiveness by reducing cases of underdiagnosis by almost 56% (from 74.4% to 20.2%), in all settings, especially in centres for drug users and in primary care,76 avoids losses in referral caused by delays, and allows a greater number of patients to be evaluated to receive treatment.70,75,76–79 A study carried out in Spain showed that the proportion of patients referred to a specialist for evaluation on the start of treatment increased from 55% to 83% when OSD was introduced.72 In another study that included populations that are difficult to access, such as drug users, the implementation of OSD led to an increase of 20.8% in diagnoses and of 32.7% in access to treatment.77 In addition, the adoption of diagnostic simplification strategies optimises available resources and time, implying a reduction in the overload of healthcare services.72

On the other hand, the OSD strategy should be complemented with the possibility of having access to computer management systems, which serve as a connection between external centres, and primary and specialised care, and achieve improvements in detection programmes and subsequent follow-up until the start of treatment. Communication between centres by introducing an automatic appointment in the event of a positive case, and even a subsequent phone call after performing a reflex test, could increase access to treatment by up to 45.2%.78 In recent years, great efforts have been made to improve diagnostic strategies in Spanish hospitals, with 89% of hospitals having implemented OSD in 2019, compared to 30% in 2017. Despite this, there is still a percentage of hospitals that use the traditional method, having the means and capacity to perform it,69,73 which is a reason for continuing to insist on the benefits it entails and promoting its use among health professionals with the aim of reducing the barriers to its diagnosis. To achieve this, the following is recommended:

- -

Simplification of the cascade of diagnosis of patients with viral hepatitis and access to treatment.

- -

The diagnosis and follow-up of the patient, in most cases, should be managed in the fewest number of consultations possible until the start of treatment.

- -

Subsequent follow-up will depend on the characteristics of the patient and the type of disease they suffer from.

There are certain vulnerable groups with high prevalence in which most of the new diagnoses of viral hepatitis are concentrated, who, due to their characteristics, do not regularly attend health services. In these groups there is a high risk of loss at all stages of the care cascade,80 and performing the test by venipuncture may mean a rejection of access to screening. The use of rapid and dried blood tests allow a decentralised diagnosis,81 that is, a serological and virological diagnosis of infections in the PoC, being a way of bringing the diagnostic test closer to populations that are difficult to access without the need for the patient to travel out of their environment, in what are called decentralised diagnostic tests.82 These tests have proven to be effective and efficient in facilitating access to screening in community settings, increasing case notification, significantly reducing time to diagnosis, increasing treatment initiation, and reducing healthcare costs,75,83–91 even in the COVID-19 era,35 in addition to showing diagnostic accuracy for evaluating viral hepatitis.75,90,92,93 Likewise, their use is viable and feasible, even for HIV, outside the usual medical care system and has excellent acceptability among users, mainly due to the lack of need for travel and the preference of offering the results on the same day or in a short period of time.90,94–98 This type of test, together with "test and treat" strategies, can also be used in prison settings,99 where the times in the care cascade are reduced by four days for screening (six vs. two days), 11 days for evaluation (14 vs. three days) and 35 days for access to treatment (36 vs. one day) compared to usual clinical management.100

Tests in the PoC13,71 make diagnostic simplification possible, as well as making it possible to carry out screening in settings outside the hospital setting, where there is no access to venipuncture tests,75 and advance towards decentralised care, reducing losses in centres for addictive behaviours or harm reduction.75,87,90,101,102 This type of technique does not require healthcare personnel, but it does require prior training to facilitate acceptance by the user.51 The results of these techniques should be incorporated into the register of the microbiology laboratories and the electronic medical record.

Recommendations:

- -

Integration of the results of the PoC tests and their supervision by the central microbiology laboratories is recommended, as well as the inclusion of the results in the patient's medical record.

- -

In order to access patients who do not go to a health centre on a regular basis (for example, people in harm reduction programmes), it is necessary to integrate screening programmes to detect patients with active infection, accompanied by a subsequent action for monitoring and treatment, if necessary.

Although diagnosis of infection has increased in recent years, there are still many people infected and not detected by the health system. Setting up alert systems incorporated into the patient's electronic medical record, based on clinical data related to the risk of infection, would help to identify and notify the specialist of the need to perform serology tests in case of any possible viral hepatitis, thus facilitating early diagnosis.103 These alerts are useful in primary care and are based on age as a risk factor,104–107 with the risk increasing between five and 15.8 times compared to usual clinical practice.106,108 Likewise, when the alert system was introduced in hospital care in the population born between 1945 and 1965, the diagnosis increased 342% in one year, as well as the link with the care and initiation of treatment (from 67% to 92% and from 32% to 18%, respectively), significantly reducing follow-up losses.107 There is also a gap between the diagnosis and the link with the care of viral hepatitis, with patients with incomplete evaluations in the system. These losses, for the most part, are caused when the request for the test is made from primary care.109 There is a variable percentage of incomplete diagnoses: around 64%110 and between 14–58%109–111 of patients have an HBsAg or anti-HCV test. With a positive result, the study with molecular techniques was never completed, or they did not reach the consultation.

The use of electronic alerts is feasible and an opportunity for improvement to enhance the detection of patients infected with viral hepatitis and their link with care and treatment112 and it is a cost-effective strategy for the health system.113

Recommendations:

- -

Inform the primary care physician and/or the specialist of the existence of viral hepatitis, through an electronic alert.

- -

The creation of automated appointment systems for the patient with the specialist is recommended. Alternatively, and if this is not possible, establish an alert system for the service in charge of managing the appointment.

Chronic viral hepatitis is a disease that usually does not present symptoms until advanced stages. For this reason, it is essential to train and raise awareness among health professionals, especially in primary care, about the importance of detecting undiagnosed cases in the general population, as well as about risk factors.13 Likewise, decentralisation of the screening and treatment process also generates the need to train non-health personnel to reduce stigma and increase screening acceptance.50 On the other hand, providing education for at-risk populations and vulnerable groups that is aimed at informing about risk factors, the consequences of liver disease and the advantages of treatment, would improve prevention, case detection and the link with healthcare services.114 In this way, a study showed that education together with tools such as electronic alerts can increase detection rates approximately 10 times.106 Similarly, civil society plays a fundamental role in the eradication of viral hepatitis,115 being key in reaching out to vulnerable populations. It is necessary to involve civil society in promoting action plans on prevention, diagnosis and treatment and get it to participate in public health interventions in different areas.116 Thus, the design of campaigns aimed at civil society would help raise awareness of the importance of viral hepatitis, in addition to reducing the stigma of the disease.

The recommendations in this regard are:

- -

It is recommended to increase the training and awareness of all health professionals, and especially primary care professionals, regarding the importance of actively seeking patients to achieve the objectives of control and elimination of hepatitis B, C and D.

- -

Intensify the role of scientific societies, through awareness campaigns and training aimed at health professionals and patients.

- -

Provide more information, in general, to civil society on the importance of carrying out a test to detect viral hepatitis, through awareness campaigns endorsed by scientific societies.

Diagnosis of infection with hepatitis B, C, and D viruses remains a public health challenge. There are still a large number of people who are unaware of their infection status. Establishing diagnosis and linkage to treatment are key to achieving the WHO 2030 target worldwide. The comprehensive diagnosis of viral hepatitis (B, C and D) from a single blood sample allows faster diagnosis, reduces the number of visits to the health centre, avoids losses to follow-up, and facilitates access to effective treatment. Likewise, decentralisation of diagnosis in the PoC helps to increase access to diagnosis and referral to medical care and treatment for the most vulnerable groups. Finally, collaboration between the different services involved in the process of finding, diagnosing and treating people with viral hepatitis is essential, and especially those related to at-risk populations and vulnerable groups, if we want to achieve its eradication in the near future.

FundingThis study has been financed by Gilead Sciences Spain (financing without conflict of interest and not conditioned on the design of the study, the collection, analysis and interpretation of the data, the writing of the article or the decision to send the article for its publication).

Conflicts of interestJavier Crespo: consultant and/or speaker and/or participated in sponsored clinical trials and/or received research grants and support from Gilead Sciences, AbbVie, MSD, Shionogi, Intercept Pharmaceuticals, Janssen Pharmaceuticals Inc, Celgene and Alexion (all outside the work here submitted).

Joaquín Cabezas: receives grants from Gilead and Abbvie; speaker for Gilead and Abbvie.

Antonio Aguilera: declares that he has no conflict of interest.

María Buti: consultant and speaker for Gilead and Abbvie.

Federico García: declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Javier García-Samaniego: speaker and consultant for Abbvie and Gilead.

Manuel Hernández-Guerra: has received research grants from Abbvie and Gilead.

Francisco Jorquera: has received personal fees from AbbVie and Gilead Sciences, and advisory and personal fees from Intercept.

Elisa Martró: has received speaker fees from Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, and Cepheid, and research grants from Gilead Sciences.

Juan Antonio Pineda: declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Manuel Rodríguez: Gilead (advice and speaker fees) and AbbVie (speaker fees).

Miguel Ángel Serra: declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Raquel Domínguez-Hernández is an employee of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia, a consultancy specialised in the economic evaluation of health interventions that has received unconditional funding from the Fundación Española del Aparato Digestivo (FEAD) [Spanish Digestive System Foundation].

Miguel Ángel Casado is an employee of Pharmacoeconomics & Outcomes Research Iberia, a consultancy specialised in the economic evaluation of health interventions that has received unconditional funding from the FEAD.

José Luis Calleja: consultant and speaker for Gilead Sciences, Abbvie, Roche, Intercept, MSD.

Scientific coordinator: Javier Crespo.

Scientific committee: José Luis Calleja, Javier Crespo, Federico García, Francisco Jorquera and Joaquín Cabezas (secretary).

Panel of experts: Antonio Aguilera, Marina Berenguer, María Buti, Joaquín Cabezas, José Luis Calleja, Javier Crespo, Xavier Forns, Federico García, Javier García-Samaniego, Manuel Hernández Guerra, Francisco Jorquera, Sabela Lens, Elisa Martró, Juan Antonio Pineda, Martín Prieto, Francisco Rodríguez-Frías, Manuel Rodríguez, Miguel Ángel Serra and Juan Turnes.

Collaborators: Raquel Domínguez-Hernández and Miguel Ángel Casado.

This publication has been endorsed or sponsored by the Spanish Association for the Study of the Liver (AEEH), the Alliance for the Elimination of Viral Hepatitis in Spain (AEHVE), the Viral Hepatitis Study Group (GEHEP) of the Spanish Society of Infectious Diseases and Clinical Microbiology (SEIMC) and the Spanish Society of Digestive Pathology (SEPD). The opinions expressed by the authors do not necessarily reflect the official position of the SEIMC.