Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is very common in the general population, with a positive IgG-based seroprevalence of 83%.1 In immunocompetent patients, it is usually asymptomatic or causes flu-like signs and symptoms. Its most common complications are acute hepatitis and splenomegaly and there may be a risk of spleen rupture. Mesenteric vein thrombosis has been reported as a rare complication of acute CMV infection.2

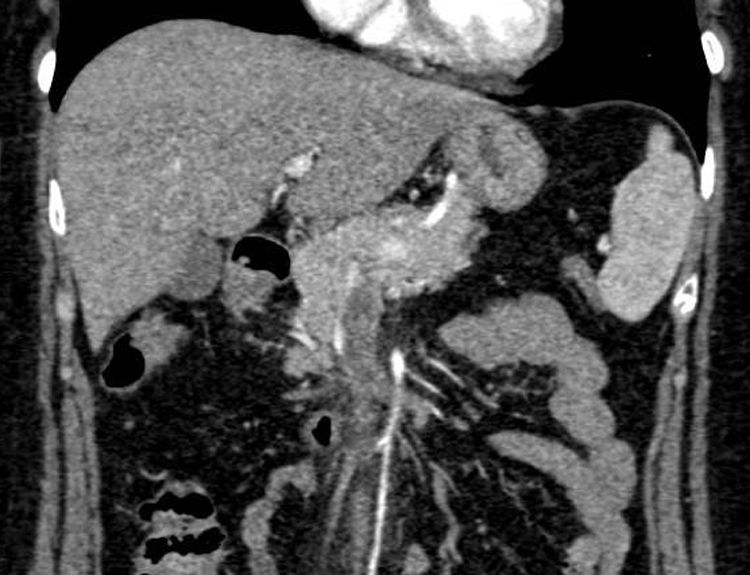

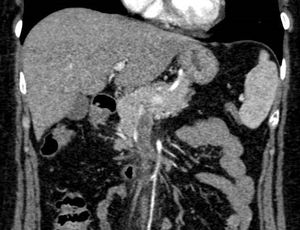

We present the case of a 55-year-old woman who was admitted for asthenia, headache and epigastric discomfort (distension). On admission, laboratory testing showed 11,650 leukocytes/μl (63.2% lymphocytes/μl), C-reactive protein 21.2 mg/l, aspartate aminotransferase 119 U/l, alanine aminotransferase 120 U/l, gamma-glutamyl transferase 113 U/l, alkaline phosphatase 179 U/l, total bilirubin 0.5 mg/dl and lactate dehydrogenase 357 U/l. On admission, an abdominal ultrasound was performed which showed hyperechogenicity of the portal vessels suggestive of oedema, no signal with Doppler ultrasound in the portal vein and hyperechogenic matter in the superior mesenteric vein, consistent with thrombosis. The study was completed with computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen, which showed a filling defect in the right intrahepatic portal vein and inside the superior mesenteric vein consistent with thrombosis. Following the CT results, treatment was started with enoxaparin at a dose of 1.5 mg/kg/day (Figs. 1 and 2). A hypercoagulability study, with determination of cardiolipin antibodies, anti-β2-glycoprotein, lupus anticoagulant, activated C protein resistance, proteins C and S, homocysteine, functional antithrombin, factor V Leyden mutation and G20210A mutation, was negative. An autoimmunity study, a haematological study with a smear, proteinogram, ß2-microglobulin and JAK2 mutation were negative, and serological test for viral forms of hepatitis and infectious causes including Brucella, Salmonella, Rickettsia conorii, Leishmania, Coxiella burnetii, Epstein–Barr virus and CMV was only positive for the CMV IgM. The study was completed with a gastroscopy and magnetic resonance imaging of the head, which yielded no findings. Given the suspicion of CMV as the main cause of the thrombosis, polymerase chain reaction (PCR) testing for CMV in blood was performed, which measured 16,600 copies/mL, thus confirming acute CMV infection. Given the aggressive form of presentation, a decision was made jointly with the infectious disease group to administer valganciclovir 900 mg/12 h for 14 days. The patient responded well, with an improvement in her symptoms after several days of antiviral treatment. Following 6 months of anticoagulation therapy with enoxaparin, a follow-up CT scan of the abdomen showed full resolution of the patient's venous thrombosis. Subsequently, the hypercoagulability study was repeated and was again negative. PCR testing for CMV in blood was also repeated and that, too, was again negative. After the patient's thrombosis and the viral infection that precipitated it had resolved, in the absence of another prothrombotic factor, a decision was made to stop her anticoagulation therapy. Subsequently, the patient remained asymptomatic, with no indicators of thrombotic relapse 6 months after her anticoagulation therapy was suspended.

Splenoportal venous thrombosis (SPVT) usually occurs in the context of an underlying cause which should be investigated and treated. The main causes of thrombosis are divided into systemic causes, such as hereditary thrombophilia, myeloproliferative syndromes, nocturnal paroxystic haemoglobinuria, systemic infections or hormone therapy. Among local causes, tumours and cysts that compress the vein tract may give rise to thrombosis.3 When SPVT is diagnosed, it is important to search for other more common thrombotic risk factors, since in many cases the cause is multifactorial. However, acute CMV infection itself can cause thrombosis. Although they are uncommon, cases of immunocompetent patients with portal and/or mesenteric vein thrombosis have been reported, in a context of acute CMV infection with no other predisposing cause, as occurred in our case.2

In general, viral infections have been linked to a higher risk of thrombosis, since they generate a systemic inflammatory response that activates coagulation through cytokine production. In particular, for CMV, it has been reported that 6.4% of hospitalised patients with acute CMV infection present venous thrombosis, the most common forms being splenic vein thrombosis and splenic infarct, though cases with pulmonary thromboembolism and deep vein thrombosis have also been observed.4 This predisposition to thrombosis is shared by other viruses belonging to the Herpesviridae family (herpes types 1 and 2) since, apart from systemic inflammation, they have an intrinsic procoagulant effect. Their viral structure consists of a covering with expression of procoagulant phospholipids capable of assembling coagulation factors Xa and Va into prothrombinase, so they are able to produce thrombin. In addition, they are expressed on the surface of tissue factor which results in activation of factor X.5 Therefore, CMV per se acts as an activator of the coagulation cascade, thereby creating a predisposition to formation of thrombi at any level. It has also been observed that acute CMV infection appears to cause a transient elevation in antiphospholipid antibodies. Once the infection resolves, their levels decrease or become negative, thus also creating in this way a predisposition to a prothrombotic state during the infection.2,4

In conclusion, we highlight the relationship between CMV and thrombotic events, which in many cases goes unnoticed, and the significance of acute CMV infection in the differential diagnosis of SPVT.

Please cite this article as: García Gavilán MC, Gálvez Fernández RM, del Arco Jiménez A. Trombosis portal y mesentérica secundaria a infección aguda por citomegalovirus en paciente inmunocompetente. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:225–226.