A 48-year-old multiparous woman was admitted with diarrhoea and abdominal pain; abdominal CT showed portal hypertension (enlarged portal vein, ascites, splenomegaly), without signs of mesenteric ischaemia. She required weekly paracentesis and parenteral nutrition. Liver disease was ruled out; hepatic venous pressure gradient less than 10 mmHg. Complete endoscopic study (absence of varices), PET/CT and laparoscopy were without findings. After prolonged hospital admission, repeat CT showed a splenic artery aneurysm fistulised to the splenic vein (Figs. 1–3). Review of the initial CT now detected the fistula, smaller in size. The fistula was treated with coil embolisation (Fig. 4), verifying during the procedure that it had disappeared. It became complicated by splenic/portal vein thrombosis, and we performed thrombectomy with partial restoration of flow. The patient improved (tolerating oral diet, reduction in ascites), and was discharged on anticoagulation therapy.

Abdominal CT scan. Cross-sectional slice. Abundant ascites (arrow). Enlarged spleen with heterogeneous density, showing hypo-attenuated areas suggestive of infarction (star). Splenic artery with distal aneurysmal dilation, associated with an image suggestive of an arteriovenous fistula (apparent communication and early filling of the splenic vein) (circle).

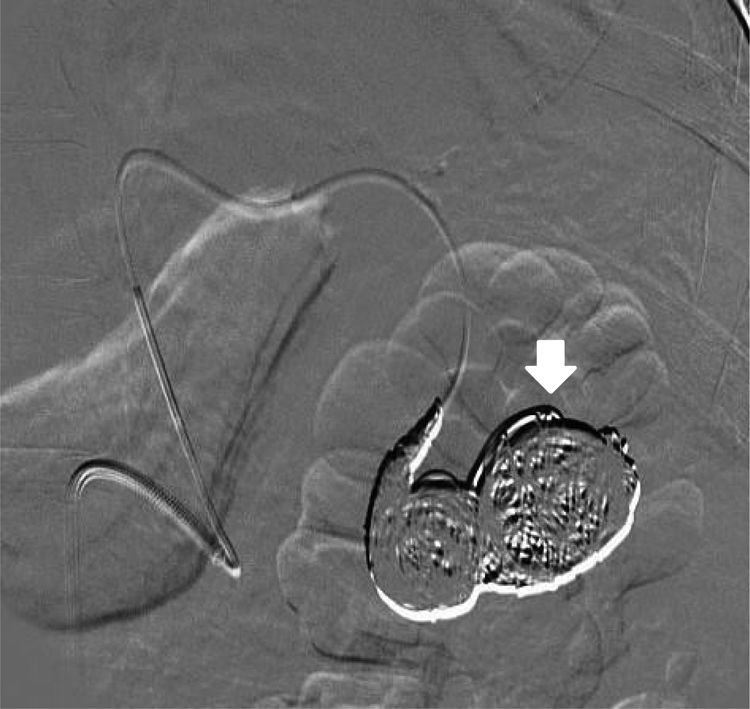

Splenic artery angiography. The splenic artery was selectively catheterised, showing a splenic-splenic arteriovenous fistula with associated splenic aneurysm. Coil embolisation was applied to both locules and the proximal entrance to the aneurysm (arrow). In the subsequent repeat test, no fistula was observed.

A splenic arteriovenous fistula can be formed by rupture of a splenic artery aneurysm into the splenic vein. They are more common in multiparous women, possibly because of damage to the arterial wall from increased visceral flow and gestational hormones.1 The risk of aneurysm rupture is estimated to be 2%–10%, with a high mortality rate.2 The signs result from congestion of the mesenteric vasculature due to portal hypertension and intestinal ischaemia due to fistula-related steal syndrome. The gold standard treatment is endovascular embolisation.3

Ethical considerationsThe authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study and they have followed the protocols of their work centre regarding the publication of patient data. They declare that in this article the anonymity of the patient has been preserved at all times and that verbal informed consent was requested for the publication of this case, and is recorded in the medical records.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.