The SARS-CoV-2 pandemic is leading to high mortality and a global health crisis. The primary involvement is respiratory; however, the virus can also affect other organs, such as the gastrointestinal tract and liver. The most common symptoms are anorexia and diarrhea. In about half of the cases, viral RNA could be detected in the stool, which is another line of transmission and diagnosis. COVID19 has a worse prognosis in patients with comorbidities, although there is not enough evidence in case of previous digestive diseases.

Digestive endoscopies may give rise to aerosols, which make them techniques with a high risk of infection. Experts and scientific organizations worldwide have developed guidelines for preventive measures.

The available evidence on gastrointestinal and hepatic involvement, the impact on patients with previous digestive diseases and operating guidelines for Endoscopy Units during the pandemic are reviewed.

La pandemia por el SARS-CoV-2 está conllevando una elevada mortalidad y suponiendo una crisis sanitaria a nivel mundial. La afectación fundamental es respiratoria; sin embargo, el virus también puede afectar a otros órganos, como el tracto gastrointestinal y el hígado. Los síntomas más habituales son anorexia y diarrea. Aproximadamente, en la mitad de los casos se podría detectar RNA viral en heces, lo que constituye otra línea de transmisión y diagnóstico. La COVID19 tiene peor pronóstico en pacientes con comorbilidades, aunque no existe evidencia suficiente en caso de patologías digestivas previas.

Las endoscopias digestivas pueden originar aerosoles, que las convierten en técnicas con elevado riesgo de infección. Expertos y organizaciones científicas a nivel mundial han elaborado guías de funcionamiento para adoptar medidas de prevención.

Se revisan las evidencias disponibles sobre la afectación gastrointestinal y hepática, la repercusión en pacientes con enfermedades digestivas previas y guías de funcionamiento para Unidades de Endoscopia durante la pandemia.

COVID-19 will mark a "before" and "after" in the history of humanity and the history of medicine, particularly with regard to acute respiratory disease, with all the infections and deaths that have occurred. However, in light of the studies that are being published, the effects that the virus is having and may continue to have on the gastrointestinal system must also be taken into consideration.

This clinical review will analyse the most significant studies published in recent weeks and months regarding compromise of the gastrointestinal tract and the liver in COVID-19. It will emphasise those which provide guidelines for ensuring the safety of patients who undergo gastrointestinal endoscopies, and of the professionals who perform these procedures, and for improving the procedures themselves, bearing in mind that these are being considered high-risk examinations during this pandemic.

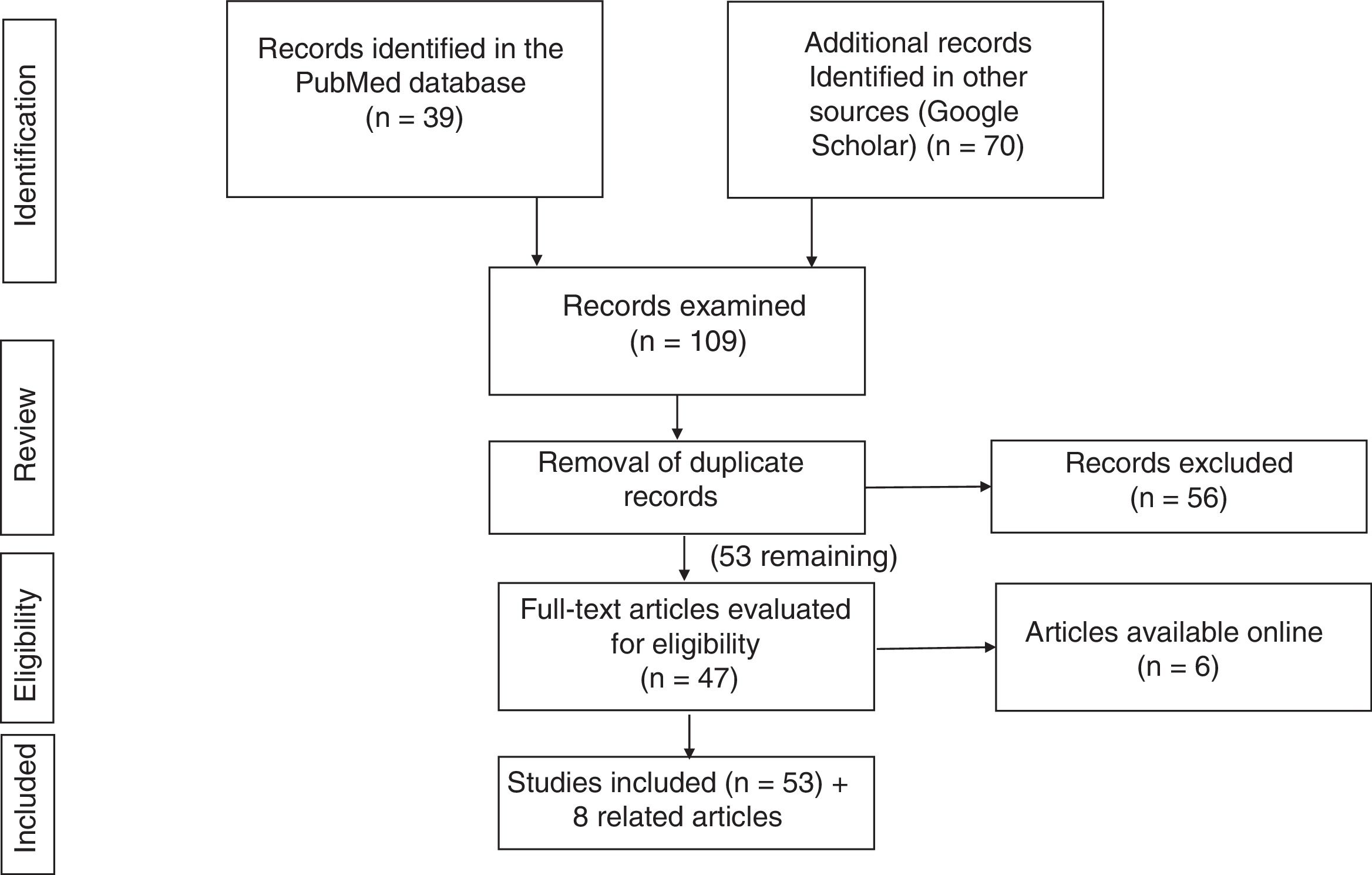

Search strategyThe literature search was performed in the PubMed (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/) and Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.es) databases, using the following keywords and filters:

- 1

PubMed: (COVID-19[ti] OR SARS-CoV-2[ti]) AND (("digestive system"[MeSH Terms] OR "digestive system"[All Fields]) OR ("gastrointestinal tract"[MeSH Terms] OR "gastrointestinal tract"[All Fields])).

This strategy turned up 37 articles; among these, those that did not suit the purpose of this review were removed, and 19 were selected.

- 2

Google Scholar: the strategy (allintitle: "COVID-19" OR "SARS-CoV-2" "gastrointestinal") yielded 70 studies.

After the results of the two literature searches were compared and duplicate records were removed, 51 studies were selected.

Fig. 1 summarises the literature search strategy and its results.

COVID-19 and the digestive tractSARS-CoV-2 infects hosts by virtue of its great affinity for angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE-2), which is highly expressed not only in lung cells but also in the epithelial cells of the bowel, mainly the small bowel, such that the virus is able to infect them.1,2 That would explain patients’ gastrointestinal symptoms, as well as the presence of SARS-CoV-2 in faeces, pointing to a route of transmission that must be taken into account in infection control efforts.3

Gastrointestinal symptoms may develop in the early stage of the disease, even before respiratory signs and symptoms appear. Hence, diagnostic suspicion of the disease, in essentially all patients with possible contact with COVID-19 recently and during the period of high incidence of the virus, will be fundamental in early diagnosis and management.4

Recent studies have indicated detection of SARS-CoV-2 by PCR in the faeces of infected patients, with a higher prevalence in those with gastrointestinal symptoms, in particular diarrhoea.5,6 The virus has been detected in faecal samples following resolution of symptoms, and even following clearance of the virus from the respiratory tract.7,8 This could represent a route of infection in addition to the respiratory route and would entail changes in measures for detection, as well as measures for management of disease propagation.9

Some cases with gastrointestinal symptoms alone have been reported,3,10 such as the first case of COVID-19 in the United States. A 35-year-old man presented with nausea and vomiting, later accompanied by diarrhoea and abdominal pain. SARS-CoV-2 RNA was detected in the patient’s faeces by PCR on day seven of his disease.11

With regard to gastrointestinal symptoms reported, various case series have agreed that the most common clinical signs are anorexia, diarrhoea, nausea, and vomiting; abdominal pain and gastrointestinal bleeding have also been reported, to a lesser extent.3,10

A recently published meta-analysis5 gathered information from series reported up to March 2020. It encompassed a total of 4243 patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19 by PCR, from 60 studies (53 from China and 7 from other countries, including one American study and one British study). In said study, the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection was 17.6%. Among them, 26.8% had anorexia, 12.5%, had diarrhoea, 10.2% had nausea and vomiting, and 9.2% had pain or abdominal discomfort. In the analysis by subgroups, statistically significant differences were found by country of origin: in China, the total prevalence of digestive symptoms was 16.1%, versus 33.4% in all other countries.

The clinical picture of diarrhoea reported, in general, is a mild course with more than 3 bowel movements per day, usually without dehydration, which habitually develops at the onset of signs and symptoms or in the course thereof. It can also be seen to be aggravated by different drugs used to treat the disease.12

The presence of gastrointestinal symptoms and the seriousness of the disease clinical course has been evaluated with variable results. In the above-mentioned meta-analysis,5 11 of the 60 studies compared them: the prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms was 17.1% in patients with disease with a serious course (95% CI: 6.9–36.7) versus 11.8% (95% CI: 4.1–29.1) in patients with COVID-19 with a non-serious course (p < 0.001; I2 = 90.9% and I2 = 97.7%).

Redd et al.13 published a multi-centre cohort study that enrolled 318 patients with COVID-19 with a high prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms: up to 61.3% presented at least one gastrointestinal symptom, but the authors found no differences in terms of the seriousness of the clinical course, need for invasive mechanical ventilation, ICU admission or mortality.

Concerning COVID-19 in patients with inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), today, there is no solid evidence on its repercussions for the course of the disease, or for the prognosis in patients with immunosuppressant treatments.14,15

A series of 86 patients at New York University Langone Health with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases and confirmed or strongly suspected COVID-19 infection did not find a worse prognosis for the viral infection.16 Similar results have been seen in other recently published series,17 which have identified neither a higher risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection nor a higher mortality rate in patients with IBD.

There has been speculation about a lower risk of secondary complications in patients with IBD as a result of the possible role of the drugs used in the management of the inflammatory cascade causing acute respiratory distress.18

In addition, owing to the frequent use of biologic drugs and immunosuppressants in patients with IBD, there is a degree of concern that those patients may be more susceptible to SARS-CoV-2 infection, although as yet there has been no report of a patient infected with this virus in a cohort of more than 20,000 Chinese patients with IBD.19

Despite this, the Chinese have already implemented several strategies to minimise the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with IBD, including particular clinical practice guidelines.20

To date, no interactions or effects of SARS-CoV-2 in the stomach, oesophagus, bile ducts or pancreas have been reported, but they could appear in the literature in due course, as virus detection methods improve.21

COVID-19 and the liverApart from gastrointestinal signs, COVID-19 patients often present liver damage.22

The data from a retrospective single-centre study conducted in Wuhan (China) in patients with SARS-CoV-2 pneumonia showed elevated ALT levels in 28% of patients and elevated AST levels in 35% of patients, as well as a slight increase in bilirubin levels (18% of cases).23 In most cases, these abnormalities were mild, transient and not clinically significant, although serious liver impairment could also occur in critically ill patients, in up to 28% of cases.24

The mechanism by which the SARS-CoV-2 virus causes liver damage is unknown. Pending the conduct of larger numbers of studies and autopsies, the following hypotheses are postulated.25,26

- -

Direct liver damage: the fact that SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in faeces may suggest possible transmission from the bowel to the liver, through the portal circulation (portal vein viraemia).27 Hepatocytes and cholangiocytes could be potential targets during infection with the virus (cytopathic effect): ACE-2 has higher levels of expression in cholangiocytes, followed by perivenular hepatocytes in the healthy liver, and cholangiocyte dysfunction could cause liver damage.28 Supporting this hypothesis, Wang et al.29 conducted a post mortem examination of 2 patients who had died of the disease and detected, for the first time, SARS-CoV-2 virus particles in the hepatocyte cytoplasm, with histological evidence of both direct cytopathic damage and intrahepatocyte virus replication. In addition, some studies have found a higher incidence of hepatic abnormality in men.30 Differences in levels of ACE-2 expression by the liver between males and females may help to account for possible clinical differences in the course of SARS-CoV-2 infection in patients with an underlying chronic liver disease.31

- -

Damage secondary to the systemic inflammatory response and stress: under normal circumstances, the liver is an organ that filters toxic substances and maintains immune tolerance, which may be affected by the hyperimmune response and cytokine storm appearing in this process.32 To date, in patients with cirrhosis, in whom there is dysfunction of the reticuloendothelial system, macrophages and the adaptive immune response, the role of these disorders in the development of a more serious form of liver disease due to the novel coronavirus is unknown.33,34

- -

A hypoxia/ischaemia–reperfusion mechanism has been reported as the most common cause of serious liver disease, secondary to pulmonary claudication, and of shock occurring in critical patients. In these patients, mention must also be made of liver damage which, collaterally, may cause liver congestion secondary to right heart failure, owing to the elevated positive pressure of mechanical ventilation.35

- -

Indirect liver damage of toxic/drug origin: the limited autopsies performed to date in patients who have died of COVID-19 have found microvesicular steatosis with mild lobular and portal inflammatory impairment of a non-specific nature, similar to that found in drug-induced hepatotoxicity.36

In regular clinical practice it is important to discern when liver abnormalities occur. In this regard, the models that stratify the risk of serious liver disease in patients with COVID-19 that have been developed note that elevated liver enzymes at the time of admission, especially those indicating hepatocellular damage (ALT and AST) and mixed damage (elevated bilirubin and GGT), prior to the use of certain hepatotoxic drugs, appear to be associated with more serious forms of lung disease and with an increased mean duration of hospital stay.37 However, these findings, which are subject to constant re-evaluation, must be confirmed in future prospective cohort studies.

During admission, the use of certain drugs, especially lopinavir/ritonavir and, at present, remdesivir and tocilizumab (as well as, to a lesser extent, hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin) is the most significant risk factor for liver damage. This points to a need for close monitoring of hepatic clinical chemistry in patients being treated with these drugs.38

In addition, the presence of comorbidities, such as obesity, diabetes and hypertension, appears to influence the prognosis of this disease caused by the novel coronavirus.

Several studies39,40 have analysed how the chronic liver impairment that occurs in COVID-19, with a prevalence of 2%-11% of patients, could influence the disease itself. To date, the number of studies is very limited and it is difficult to assess any such impact, but cohort studies and a recent meta-analysis of 5 studies comparing disease progression in patients with or without prior chronic liver disease have indicated that chronic liver disease does not seem to significantly influence the seriousness or the course of the disease (OR: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.30–1.49; p = 0.326). However, in the studies analysed, the precise cause of the chronic liver disease developed has not been published, and the number of such studies is insufficient.

Moreover, the cohort studies that have analysed the course of COVID-19 in patients with viral hepatitis (hepatitis B)41 and those that have assessed the impact of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease on the disease due to the novel coronavirus, especially in the absence of obesity, have concluded that there is a higher risk of developing a serious form of pneumonia and having more prolonged hospital stays,42 although the available data in this regard remain insufficient.

Regarding patients with autoimmune hepatitis, to date, there is no scientific evidence endorsing or advising a decrease or change in immunosuppression, which could even cause reactivation of the disease and worsen its prognosis. However, it seems appropriate to stratify risks of developing complications, closely monitor these patients during infection and propose reduction of immunosuppression, particularly antimetabolites, in patients who present lymphopenia or a worsening of the course of the disease.43

Other questions have yet to be answered, such as what short-term and long-term effects the triggered immune cascade could have in COVID-19, in pre-existing liver diseases44 such as steatosis; how SARS-CoV-2 could impact cholestatic liver diseases (primary biliary cholangitis and primary sclerosing cholangitis), through ACE-2 receptors; and what repercussions liver damage incurred in COVID-19 could have for patients with less hepatic reserve.

With a view to offering answers to these questions in the future, the universal, collaborative COVID-Hep/SECURE Cirrhosis registry has been developed in order to ascertain how pre-existing liver disease and liver transplantation affect the course of COVID-19, and to collect patient factors such as age, sex, comorbidity and medication used to analyse their influence on the course and outcomes of the disease.

The registry is updated on a weekly basis. In the latest update, of 12 May 2020, the controlled cohort was 491 patients; up to that date, notably, there was a 36% mortality rate in patients with cirrhosis — much higher than the mortality rate in other patients with non-cirrhosis chronic liver disease (7%) and that in patients with a liver transplant (20%). These data will continue to be analysed as the registry continues to be developed (see at https://www.covid-hep.net/updates.html).

Gastrointestinal endoscopy in the context of COVID-19The gastrointestinal endoscopy procedure may generate aerosols with a high capacity for infection. This means that this technique, in all its modalities, must be considered an examination with a high risk of infection and preventive measures must be put in place for all endoscopy staff.

In this regard, some experts and various scientific organisations around the world have hastened to prepare various operational guidelines for gastrointestinal endoscopy units during the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic.

All these guidelines have been updating their initial recommendations as the pandemic has unfolded. In general, all of them are in agreement on their end goals45: to protect all healthcare workers involved in performing gastrointestinal endoscopy procedures, as well as patients and caregivers, and to keep endoscopy units operational in terms of quantity and, above all, quality/safety.

To achieve these objectives, all the guidelines concur, more or less, on matters such as:

- 1

Reorganisation of endoscopy unit working agendas.

- 2

Assessment/screening for the infection risk of the patient and the endoscopy technique.

- 3

Use of personal protective equipment and its suitability according to risk.

- 4

At-home follow-up of the patient and the staff.

- 5

Disinfection of endoscopy materials and waiting rooms.

Below is a review of the published guidelines and recommendations from different countries and continents with an attempt made at distilling the points they have in common and the points on which they do not entirely agree.

The following were reviewed: from the United States, the guidelines of the American Gastroenterological Association (AGA),46 the American College of Gastroenterology(ACG) and the American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE);47 from Europe, the guidelines of the European Society Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Nurses and Associates (ESGENA);48 from Spain, the guidelines of the Sociedad Española de Patología Digestiva (SEPD)-Asociación Española de Gastroenterología (AEG) [Spanish Association of Gastrointestinal Disease (SEPD)-Spanish Association of Gastroenterology (AEG)];45 from the Asia-Pacific region, the guidelines of the Asian Pacific Society of Digestive Endoscopy (APSDE);49 from the United Kingdom, the guidelines of the British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG);50 from Japan, the guidelines of the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society (JGES);51 from Saudi Arabia, the guidelines of the Saudi Gastroenterology Association (SGA);52 and from India, the guidelines of the Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy of India, the Indian Society of Gastroenterology and Indian National Association for the Study of the Liver (SGEI-ISG-INASL).53

Recommendations from China,54 Italy,55 Singapore,56 Australia (Gastroenterological Society of Australia [GESA])57 and the World Endoscopy Organization (WEO)58 were also reviewed.

Regarding the reorganisation of endoscopic activity, all the sources consulted agree on decreasing the number of examinations in order to prevent overcrowding of endoscopy areas and contagion among staff, and on allowing ventilation of rooms and saving on equipment and protective materials.

All organisations45–58 recommend prioritising emergency examinations: upper and lower gastrointestinal bleeding with haemodynamic repercussions, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in cases of obstructive acute cholangitis, acute dysphagia, obstruction requiring stent placement and gastrostomy placement when feeding cannot be delayed.

They agree that all other indications should be delayed by up to 12 weeks, or even longer. Such is the case of screening endoscopies, follow-up endoscopies and endoscopies in patients without warning symptoms. However, some guidelines45,50 have established an intermediate level, with debatable indications, some of which should be done before said 12-week period has elapsed, assessing the risk of diagnostic delay, the patient’s condition and the hospital’s circumstances, as well as the availability of other support services, such as surgery, radiology and oncology.

The risk of infection seems to depend more on the patient than on the type of examination; however, regarding the latter, there are differences among the sources consulted. Some recommendations45,55 consider colonoscopy to be a low-risk or intermediate-risk technique, whereas all others46,56–58 make no distinction between upper and lower endoscopy.

Regarding assessment of patients’ risk of infectiousness, all the sources consulted45–58 recommend screening with a clinical interview 24 h before and on the day of the test. Fever, cough, dyspnoea and gastrointestinal symptoms (diarrhoea) in the past 2 weeks with no apparent cause, as well as patients’ potential contact with patients with confirmed COVID-19, are to be investigated.

The ASGE47 also recommends that patients’ temperature be taken the day before (by patients themselves) and the day of the examination, on the endoscopy unit. Based on this screening, patients are considered to have a low, intermediate or high risk of infectiousness.

Most organisations45,49–54,56–58 have no low level of risk of infectiousness, and refer only to intermediate risk (no symptoms) and high risk (symptoms, contact or confirmed COVID-19 diagnosis). Only patients who had and recovered from the infection and had a negative PCR would be low risk. All guidelines45–58 agree on delaying endoscopies in patients with a high risk, except in cases of an emergency indication or any other that cannot be delayed.

Only some institutions45,48,53,55 recommend that the patient visit the hospital accompanied by a single family member, if possible one under age 65, who must remain outside the unit for the duration of the procedure.

Among the sources consulted, only the SEPD, the ESGE and the Chinese source45,48,54 recommend that patients wear a surgical face mask as long as they are on the unit. The ASGE and the Indian guidelines47,53 only recommend this if the patient has symptoms. All other associations make no mention of this matter.

All the guidelines45–58 agree on applying general measures (hand-washing before and after each examination, observance of social distancing, and use of surgical face masks outside of rooms), training stable working teams, avoiding the transfer of endoscopists to potentially infected areas, using one computer per physician and cleaning work stations daily with a specific disinfectant solution.

Regarding personal protective equipment, several of the sets of guidelines consulted47,48,50,53,57,58 recommend that unit staff receive specific training in its use.

The AGA and most organisations46,47,50–54,56–58, for their part, recommend using FFP2 and FFP3 face masks for procedures with a risk of generating aerosols and make no distinction between upper and lower endoscopy.

The SEPD, the ESGE, the APSDE and the Italian group45,48,49,55 recommend the use of surgical face masks in low-risk and moderate-risk patients, both in gastroscopies and in colonoscopies.

As regards gowns, most associations46,56–58 recommend using waterproof gowns. The SEPD and the Italian group45,55 advocate for single-use surgical gowns in low-risk and moderate-risk procedures and patients.

All the organisations consulted recommend wearing nitrile or latex gloves, and one of them48 recommends wearing two pairs of gloves for high-risk patients.

After performing an endoscopy on a high-risk patient or a patient with confirmed COVID-19, the waterproof gown and face mask used should be discarded. In the event of a shortage of the latter, the AGA46 recommends covering face masks with a surgical face mask to reuse them and extend their hours of use, and thus save materials (limited evidence).

There is a consensus on using goggles, or a face shield, and a disposable cap in all examinations, and on using a specific room and specific staff in high-risk patients and patients with confirmed COVID-19.

Among the guidelines reviewed, the AGA-ASGE and the ESGE47,48 recommend patient follow-up once the patient leaves the hospital, after 7 and 14 days, in which the patient is asked about the onset of any new symptoms that might be suggestive of COVID-19.

Any member of the unit with symptoms consistent with COVID-19 should abstain from going to work and must contact the hospital’s occupational health unit to take the appropriate measures.

The guidelines45–58 are consistent in all matters related to cleaning/disinfection and processing of endoscopes and materials from working rooms:

The usual disinfectants must be used; peracetic acid has demonstrated efficacy against bacteria, mycobacteria viruses and fungi. All materials should be transported to the washing area in sealed plastic bags. Endoscopes should be washed by hand before being placed in washers. Auxiliary materials should be single-use and must be discarded in specific containers. All surfaces and objects that have come into contact with the patient or the patient’s secretions (bed, railings, pulse oximeter, floor, toilet, endoscopy tower, etc.) must be disinfected following each examination with a sodium hypochlorite/bleach solution in a 1:100 dilution.

Following examination of an intermediate-risk patient, the room must remain empty and be ventilated for at least 30 min. For high-risk patients and patients with confirmed COVID-19, this period should be 60 min.

Regarding the risk of infection for healthcare staff and efficacy of protective measures, Repici59 published the retrospective experience of 42 endoscopy units in hospitals in Italy, with 968 healthcare workers investigated altogether. A total of 42 tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 (23 physicians, 16 nurses and 3 auxiliary staff members). Of these, 36 had respiratory symptoms and just 2 had gastrointestinal symptoms. Only 6 healthcare workers required admission to a unit and were discharged after a mean stay of 8 days. Some 70% of the units (with a total of 671 healthcare workers) reported no cases of infection. Three centres accounted for 55% of positive cases, most of which occurred before the strict protective measures recommended in Italy were put in place (8 March).

The analysis showed that the rate of infection among endoscopy staff was very low, just 4.3% — far lower than 10%, which was the estimated rate in Italy for healthcare staff during the crisis. Most of the 968 healthcare workers wore only surgical face masks, reserving N95 and equivalent face masks for infected and high-risk patients.

How to resume endoscopic activity following the cessation of the current outbreak?46,49,60

Before activity is resumed, several factors must be taken into consideration, such as the actual COVID-19 situation in a hospital and health area; agendas must be gradually reopened; numbers of pending examinations must be determined; indications must be re-evaluated; levels of priority (high, medium and low) must be assigned to indicated tests; screening must be carried out for risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection by conducting medical histories and taking all patients’ temperature; availability of personal protective equipment and protective materials for all staff must be ensured; and working protocols must be established.

The first point is extremely important, and some guidelines link the increase in activity in the different indications (emergency, preferential and elective) to the number of cases of infection seen. Where there are a high number of cases, urgent and emergency cases must be prioritised. Subsequently, activity will be increased to address preferential cases, then elective cases, as the number of new infections decreases, until 100% activity is recovered in all subgroups. But when? No one knows yet.

The new situation into consideration in agendas and examination times must be lengthened. When the number of new infections is low, in de-escalation, activity can be gradually resumed in accordance with the previously established prioritisation plan. In this situation, restarting endoscopic studies must be considered in patients with gastrointestinal bleeding with no signs of instability, resection of complex colon polyps, when onset of IBD is suspected, if there are gastrointestinal signs and symptoms with warning symptoms, with symptoms raising suspicion of colorectal neoplasm or with a positive result for a faecal occult blood test, in rescheduling ligature of risk varices and in resuming diagnostic/staging studies with suspected pancreatic neoplasm (endoscopic ultrasonography).

The new normal will require all staff belonging to gastrointestinal endoscopy unit teams to continue routinely using general standards for infection prevention and, as long as there are cases and there is a high risk of the spread of the virus in the community, all patients must be considered to be potentially infected. Hence, personal protective equipment must continue to be used in all endoscopic examinations, despite the inconveniences and delays in examinations that this may entail.

Conflicts of interestThe authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Please cite this article as: Sanz Segura P, Arguedas Lázaro Y, Mostacero Tapia S, Cabrera Chaves T, Sebastián Domingo JJ. Afectación del aparato digestivo en la COVID-19. Una revisión sobre el tema. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:464–471.