The interest to use telemedicine rapidly expands as the COVID-19 outbreak does. Before the pandemic, we already lived times of overwhelmed consultations with financial constraints, and the promise of telemedicine for improving access to better health services at lower costs drew attention to its use. Paradoxically, the exponential increase in the number of articles over years led to an asymptotic evolution that rarely reaches the implementation of telemedicine in daily practice and policy.1 The use of information and communication technologies (ICTs) for health practice faced several challenges explaining why many telemedicine projects fail to scale-up, despite the technical advances made since the term “telemedicine” was coined about 50 years ago. Then, will this pandemic trigger a deep implementation of telemedicine never seen earlier?

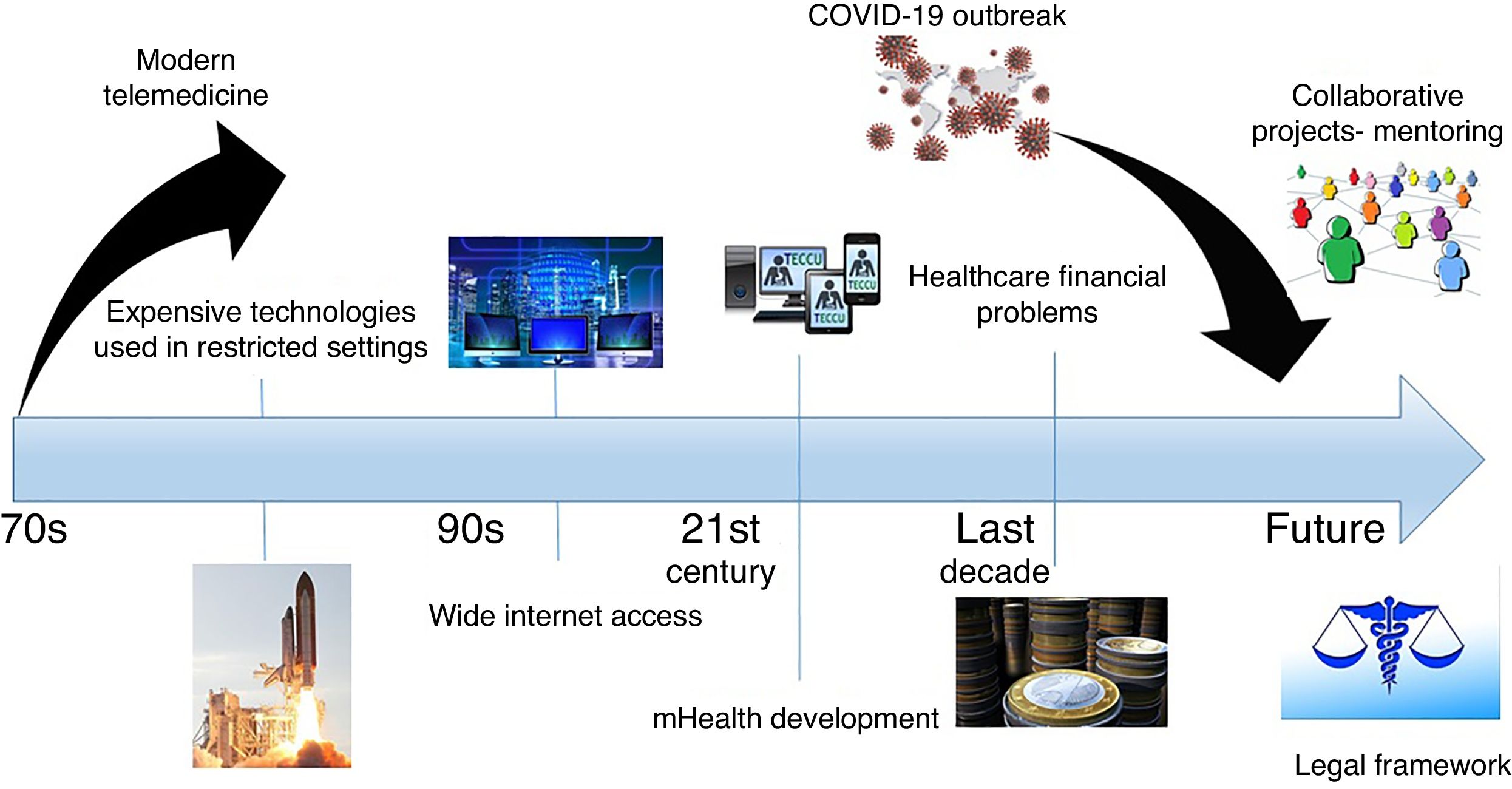

During the first steps of modern telemedicine, the limitations were mainly technical or procedural, with high costs associated to the communication tools that only allowed their use in restricted settings such as spatial or military applications. Over time, the digitalization in telecommunications and the progressively wider access to the Internet offered an opportunity to reorganize healthcare services. The increase of data transmission and storage capacity, as well as the evolution of mHealth with the development of wireless communications, provided us a broad range of easy-to-use devices adaptable to many aspects of our practice remotely. Furthermore, the incorporation of artificial intelligence and Big data to analyze massive volumes of information could potentially improve healthcare systems to facilitate tailored medicine.

It has been a long way to go, and still the development of more powerful and cheaper communication tools turns technical challenges into legal, ethical, economical and professional issues. Unlike the use of ICTs in other fields (streaming entertainment services, grocery delivery, e-banking, etc.), telemedicine interventions deal with the need to integrate patient-generated data into electronic health records, while privacy is essential in the processing of sensitive data. Moreover, the efficacy of telemedicine on health outcomes is inconsistent across different programs used in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), and their value is difficult to establish when only few economic data are available. Thus, decision-makers have difficulties to support the implementation and investment on telemedicine due to a lack of solid evidence. In addition, these decisions become even more complicated in areas were reimbursement is an important factor in the setup of clinical activity.

At this point, are we ready to transform COVID-19 crisis into a revolution? As other disasters, the pandemic leads to a surge in demand for healthcare services, which directly and indirectly could collapse health systems. To solve this problem, telemedicine offers two main advantages. On the one hand, the classical benefit of providing healthcare at a distance may serve to start-up efficient triage services without exposure to SARS-CoV2.2 On the other hand, components like tele-education and telemonitoring that provide action plans can promote patients’ empowerment and self-management. The combination of these two benefits could alleviate our previously overwhelmed healthcare capabilities not only during the pandemic, but also in our daily practice.

Telemedicine triage systems could classify IBD patients into different categories both considering the risk of serious COVID-19 disease and IBD flare. With this approach, even quarantined providers can continue working and IBD patients with COVID-19 disease can receive quality healthcare in a safe manner for staff, other patients and general population. It is possible to use telephone to perform triage and clinical appointments. Many centers count on telephone and email helplines, ideally attended by specialized nurses, to answer patients’ queries regarding treatment, the risk of infection or the IBD itself. In centers that previously implemented mature telemedicine programs, these new tools may offer personalized follow-up and multidisciplinary advice, even using automated algorithms (with the providers’ support) to standardize practice patterns. If accessible, new systems can include point of care (PoC) fecal calprotectin testing in combination with validated patient reported outcomes.

IBD represents a heterogeneous group of disorders mostly affecting young individuals in their optimal period of personal and professional development. The use of ICTs is a potential solution to manage these patients, but telemedicine mainly focused on other chronic conditions such as depression, diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases. The development of more sophisticated telemedicine programs and PoC testing over the last years provides additional value to remote follow-up in the IBD context, improving the ability to cover different patients’ profiles more objectively.

In this sense, our research group developed a web-based platform called TECCU (“Telemonitorización de la Enfermedad de Crohn y ColitisUlcerosa” or Telemonitoring of Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis). In a previous pilot trial, TECCU showed to be a safe strategy to improve health outcomes of complex IBD patients,3 with a high probability of being more cost-effective in the short term compared to standard care and telephone care.4 In view of these results, a new project in collaboration with other hospitals and investigators from the Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis (GETECCU) and the confederation of associations for patients with Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis of Spain (ACCU) is currently underway (Fig. 1).

In any case, to reorganize IBD health practice definitely we should waive the previous brakes in the adoption of telemedicine, but we must also know how to drive the new situation (Fig. 2). First, it is necessary to standardize remote medical practice. In the US, the Interstate Medical Licensure Compact was created to increase efficiency in multistate licensing of physicians,5 but such a proposal is lacking in Europe. Second, those organizations that previously investigated the value of telemedical innovations should lead this revolution,6 with the collaboration between centers and regions to develop the European health strategies. Third, institutions lacking telemedicine programs can outsource these services, but the provision of remote health safely also requires a uniform legal framework regarding medical liability. Finally, in order to maintain adherence to follow-up it is essential to adapt telemedicine programs according to patients’ requirements.

Maybe the pandemic has reduced reluctance amongst physicians to use telemedicine, but funders, policy-makers, providers and patients need to align their interests to implement remote healthcare successfully. As an example, on March 6, 2020 it was signed into law an emergency bill of more than $8 billion passed by the US Congress to face COVID-19. Part of this funding package includes the Telehealth Services During Certain Emergency Periods Act of 2020,7 in order to temporarily lift certain restrictions on Medicare telemedicine coverage in the efforts to contain the virus.

Therefore, telemedicine offers many opportunities to overcome healthcare challenges posed in the management of IBD during the COVID-19 outbreak, as long as we know how to use these resources properly. In spite of the use of telephone and e-mail in many centers, the development of mature telemedicine programs integrated with electronic health records requires further collaborative efforts between different investigators. Telemedicine intends to reorganize (not to replace) healthcare systems, and decision-makers still need more evidence on the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of its use in IBD prior to perform important changes. Even if we assume that the pandemic could reduce reluctance to use telemedicine, specific European regulation is required to protect remote medical practice and to lift some existing legal barriers.