Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is common and usually associated with HCV chronic infection and HFE polymorphisms. Since DAA IFN-free regimens availability, SVR for HCV is nearly a constant and we wonder whether HCV SVR determine PCT evolution.

MethodsRetrospective observational study including patients with HCV associated PCT from the Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases Departments at our Hospital, treated with DAA (Apr/2015–Apr/2017). Clinical variables of PCT were collected at PCT diagnosis, after PCT treatment, before DAA use and after SVR achievement. UROD activity and C282Y/H63D polymorphisms were registered. SPSS 22.0.

Results13 HCV-PCT patients included: median age 52.5 years; 4 females; 8 HCV/HIV co-infected (all on undetectable viral load). Classical PCT factors: 12 smoked, 9 alcohol abuse, 6 former IDU. 10 type I PCT and 1 type II PCT. HFE polymorphism: 2 cases with C282Y/H63D; H63D polymorphism in 8. PCT manifestations resolved with PCT treatment in 4 patients, almost completely in 7 patients, 1 patient referred stabilization and one worsened. After DAA treatment all the residual lesions resolved, what always led to specific treatment interruption.

ConclusionsOur series of cases of HCV-associated PCT shows that SVR after DAA treatment leads to PCT resolution. Porphyrin levels are not needed after ending PCT specific treatment interruption when there are no residual skin lesions in HCV-associated PCT.

La porfiria cutánea tarda (PCT) es un trastorno frecuentemente asociado con la infección por VHC y los polimorfismos HFE. Desde la aparición de los AAD en regímenes libres de IFN, la RVS para el VHC es casi universal. Nos preguntamos si la RVS del VHC determina la evolución de la PCT asociada al VHC.

MétodosEstudio observacional retrospectivo con pacientes con PCT asociada al VHC atendidos en Gastroenterología y Enfermedades Infecciosas en nuestro centro, tratados con AAD (abril 2015 - abril 2017). Se registra información relacionada con la PCT en el momento del diagnóstico, tras iniciar tratamiento para la PCT, antes de AAD y tras RVS. Analizamos la actividad UROD y los polimorfismos C282Y/H63D. SPSS 22.0.

ResultadosSe incluyen 13 pacientes con PCT asociada al VHC: edad mediana 52,5 años; 4 mujeres; 8 coinfectados VHC/VIH (todos con VIH indetectable). Factores asociados a PCT: 12 fumadores, 9 alcohol, 6 ADVP. Hubo 10 PCT clasificadas como tipo I y una PCT tipo II. HFE: 2 casos C282Y/H63D; H63D presente en 8. Tras iniciar tratamiento clásico para PCT los síntomas se resolvieron completamente en 4 casos, casi completamente en 7, se estabilizaron en un paciente y empeoraron en un paciente. Tras la RVS con AAD desaparecieron las lesiones residuales en los pacientes que las presentaban, lo que llevó a interrumpir todos los tratamientos para la PCT.

ConclusionesNuestra serie de casos de PCT asociada al VHC muestra que la RVS para el VHC tras AAD conduce siempre a la curación de la PCT. Según esto no sería necesaria la determinación de porfirinas tras finalizar la terapia específica para la PCT cuando no haya lesiones cutáneas residuales en la PCT asociada al VHC.

Porphyria cutanea tarda (PCT) is the most frequent of all porphyrias, a group of diseases involving alterations in the heme metabolism. When uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase (UROD) function drops below 20% of normal activity, uroporphyrins accumulate in the liver and later to the bloodstream from where they are eliminated through urinary excretion. However, uroporphyrins may accumulate in the skin where, when exposed to sun radiation, produce a tissular damage responsible of the main cutaneous manifestations in PCT disease: blisters, scars and other skin lesions in photo-exposed areas.1

Type I (spontaneous) PCT involves 80% of all PCT cases, whereas type II and III (associated to UROD genetic mutations) are less frequent in our area due to the lower incidence of these polymorphisms.2 To date, chronic HCV infection (with or without hepatopathy) is one of the most important acquired factors associated to PCT. The reason why HCV favours UROD dysfunction is apparently multifactorial and is not clear at all.3 Other classical factors are hereditary haemochromatosis (HH) or hemosiderosis, chronic hepatopathy/cirrhosis, and other secondary factors such as alcohol, smoking, arterial hypertension, exogen oestrogens, or diabetes mellitus.1

HFE gene polymorphisms are associated with the emergence of any type of PCT. In the presence of C282Y and H63D there may be relevant hepatic iron accumulation even without clinical manifestations of HH. Therefore, both HFE mutations are linked to PCT. What is more, the presence of isolated H63D, which is not thought to be enough to trigger HH, has been associated with PCT.3 The relation between HH and PCT is marked by a common pathophysiology and by a similar therapeutic approach, as the standard of care for both pathologies consists on phlebotomies to reduce iron tissue overload.

There are several non-specific clinical manifestations of PCT which make diagnosis very complex. Consequently, it requires an expert dermatological exam plus a urine porphyrins test, always supported by the pathological anatomy of lesions.1 Classical treatment is based on hepatic iron depletion (phlebotomies or iron chelating agents) combined in some cases with chloroquine. Treatment usually achieves clinical control after some months4 but in case of further iron repletion there may be a clinical relapse in up to a 10–50% of patients, requiring new cycles of interventions.5

In our area a great proportion of PCT is associated to chronic HCV infection.6,7 In this context, HCV treatment is key for PCT control. Former HCV treatments based on interferon (IFN) and ribavirin (RBV) are nowadays considered insufficient, and they could even trigger or worsen PCT skin manifestations.8 Direct acting antivirals (DAA) for HCV in interferon free regimens provide a great opportunity for PCT patients as they are simple and well tolerated, and they get to rates of sustained virologic response (SVR) higher than 90–95%. There is already some evidence that DAA may improve symptoms in HCV associated PCT,9–14 and normalization of asymptomatic porphyrinurias has been described in a series of patients after HCV elimination.18

After more than 4 years of experience treating HCV with IFN-free DAA regimens we sought to clarify the outcome of PCT in HCV-infected people after SVR for HCV is achieved by IFN-free DAA regimens.

MethodsWe designed a retrospective observational study including patients with chronic HCV infection and PCT from the Gastroenterology and Infectious Diseases Department in “Hospital Universitario de La Princesa” in Madrid, collecting information since DAA-IFN free regimens availability (April 2015) until April 2017. The patients included from the Infectious Diseases Department (who were HCV-HIV co-infected because of our clinic logistics) were selected after reviewing systematically all the DAA treated patients in this department, whereas the HCV mono-infected patients from the Gastroenterology Unit were collected from their series of cases with PCT. We excluded the HCV-infected patients who had achieved SVR with IFN base regimens (even when associated to DAA).

A systematic retrospective medical history review was performed, registering demographical data, toxic exposure history and classical factors linked to PCT. Within HIV patients we collected CD4 count cell and viral load (<50cop/ml). About HCV infection we registered the regular clinical data about this condition, specifically including information about hepatic involvement and the specific DAA regimen applied. Regarding PCT we collected data about clinical symptoms at diagnosis, PCT treatment before DAA availability (phlebotomy or chloroquine) and the evolution of clinical findings and treatments after PCT before and after DAA associated SVR; the tests which led to PCT diagnosis were also collected. Biochemical parameters were collected at the time of PCT diagnosis and in the different evolving times of the disease until SVR. Within these, measured porphyrin urinary levels have been collected when PCT was diagnosed and after achieving SVR. We collected the UROD activity in peripheral blood and HFE C282Y/H63D polymorphisms.

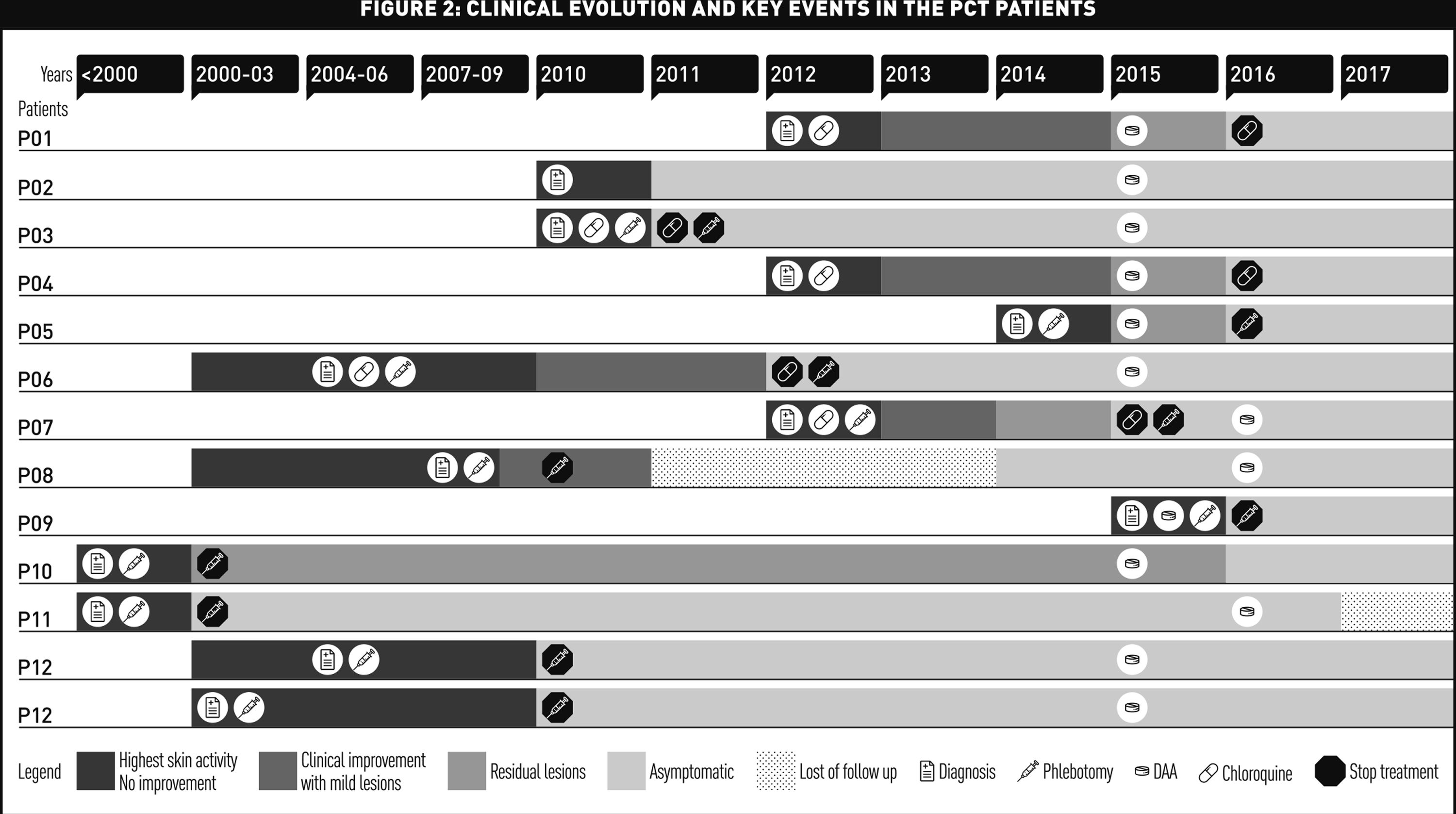

When collecting clinical information about skin symptoms evolution from medical histories, we could only register information about improvement or worsening of symptoms from the physicians written comments. Because of that we recorded that information in a semiquantitative way referring “highest activity/no improvement – clinical improvement/mild lesions – residual lesions – complete clinical resolution/asymptomatic – lost follow up”.

In those cases where genetic tests were not available in the retrospective research, we contacted the patient clinicians to make them consider requesting this information afterwards. That genetic tests were performed by our geneticist clinician collaborator who asked the patients for an informed consent as she does according to good clinical practice in genetic research, and who communicated the results to the patients offering them genetic counselling when required.

The quantitative variables are referred as median and 25–75th percentile [med (25p–75p)]; qualitative variables are referred by their numeric value and percentage. Wilcoxon test was performed to analyze statistical significance of changes in laboratory parameters. Lost information is not included in the analysis and data is considered in a “per protocol” approach. Descriptive analysis has been executed using SPSS 22.0.

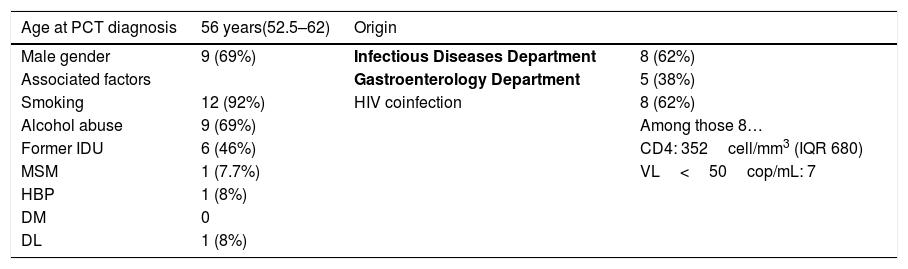

ResultsThirteen patients were included in the study. Table 1 shows demographic and PCT parameters in the time of diagnosis (baseline).

Baseline parameters. Med (25p–75p)/N (%) – N=13.

| Age at PCT diagnosis | 56 years(52.5–62) | Origin | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male gender | 9 (69%) | Infectious Diseases Department | 8 (62%) |

| Associated factors | Gastroenterology Department | 5 (38%) | |

| Smoking | 12 (92%) | HIV coinfection | 8 (62%) |

| Alcohol abuse | 9 (69%) | Among those 8… | |

| Former IDU | 6 (46%) | CD4: 352cell/mm3 (IQR 680) | |

| MSM | 1 (7.7%) | VL<50cop/mL: 7 | |

| HBP | 1 (8%) | ||

| DM | 0 | ||

| DL | 1 (8%) |

Med (median), p (percentile), N (number), IDU (injected drug users), MSM (men who have sex with men), HBP (high blood pressure), DM (diabetes mellitus), DL (dyslipidemia), VL (viral load), cop (copies).

The symptoms referred at PCT diagnosis were “blisters in photo-exposed areas” in 11 (85%) patients, “scars in photo-exposed areas” in 4 (31%) and hypertrichosis in 1(8%). Urinary porphyrins (total, uroporphyrin and coproporphyrin) were elevated in the 8 patients who had this information available (100%). Skin biopsy was performed in 9 patients: 6 (66%) showed characteristic PCT subepidermal blister. Urinary porphyrin levels (coproporphyrin and uroporphyrin) were found in 8 of the patients, being over normality levels in all of them and thus confirming PCT diagnosis.

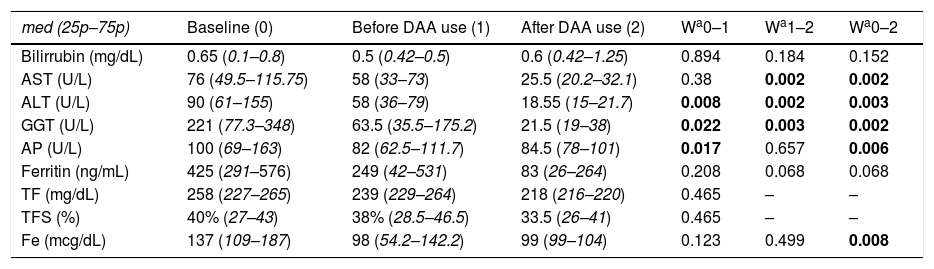

Table 2 shows the biochemical parameters at baseline time and during follow up.

Biochemical parameters.

| med (25p–75p) | Baseline (0) | Before DAA use (1) | After DAA use (2) | Wa0–1 | Wa1–2 | Wa0–2 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilirrubin (mg/dL) | 0.65 (0.1–0.8) | 0.5 (0.42–0.5) | 0.6 (0.42–1.25) | 0.894 | 0.184 | 0.152 |

| AST (U/L) | 76 (49.5–115.75) | 58 (33–73) | 25.5 (20.2–32.1) | 0.38 | 0.002 | 0.002 |

| ALT (U/L) | 90 (61–155) | 58 (36–79) | 18.55 (15–21.7) | 0.008 | 0.002 | 0.003 |

| GGT (U/L) | 221 (77.3–348) | 63.5 (35.5–175.2) | 21.5 (19–38) | 0.022 | 0.003 | 0.002 |

| AP (U/L) | 100 (69–163) | 82 (62.5–111.7) | 84.5 (78–101) | 0.017 | 0.657 | 0.006 |

| Ferritin (ng/mL) | 425 (291–576) | 249 (42–531) | 83 (26–264) | 0.208 | 0.068 | 0.068 |

| TF (mg/dL) | 258 (227–265) | 239 (229–264) | 218 (216–220) | 0.465 | – | – |

| TFS (%) | 40% (27–43) | 38% (28.5–46.5) | 33.5 (26–41) | 0.465 | – | – |

| Fe (mcg/dL) | 137 (109–187) | 98 (54.2–142.2) | 99 (99–104) | 0.123 | 0.499 | 0.008 |

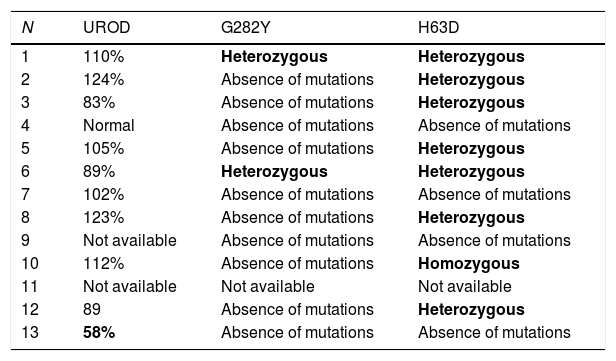

UROD enzyme activity could be tested in 10 of our patients, showing just 1 case (10%) of UROD genetically reduced activity. The HFE polymorphisms were determined in 11 patients: 9 (81.8%) showed an absence of mutations in C282Y loci and 2 patients showed a heterozygous condition in this gene. Regarding H63D: 4 patients did not show any mutation, 7 (63.6%) had a heterozygous condition (of which 2 were also associated with a mutation in C282Y) and 1 showed a homozygous condition for these loci. This information is synthetized in Table 3.

Baseline genetic parameters.

| N | UROD | G282Y | H63D |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 110% | Heterozygous | Heterozygous |

| 2 | 124% | Absence of mutations | Heterozygous |

| 3 | 83% | Absence of mutations | Heterozygous |

| 4 | Normal | Absence of mutations | Absence of mutations |

| 5 | 105% | Absence of mutations | Heterozygous |

| 6 | 89% | Heterozygous | Heterozygous |

| 7 | 102% | Absence of mutations | Absence of mutations |

| 8 | 123% | Absence of mutations | Heterozygous |

| 9 | Not available | Absence of mutations | Absence of mutations |

| 10 | 112% | Absence of mutations | Homozygous |

| 11 | Not available | Not available | Not available |

| 12 | 89 | Absence of mutations | Heterozygous |

| 13 | 58% | Absence of mutations | Absence of mutations |

UROD (uroporphyrinogen decarboxylase).

Prior to the availability of DAA, 7 patients were treated exclusively with phlebotomies and 2 exclusively with chloroquine. 3 patients required a combination of both treatments and 1 patient did not require any treatment at the time. Biochemical parameters after PCT specific treatment, before DAA use, and 12 months after receiving DAA are shown in Table 2.

After PCT specific treatment, but before DAAs, an evident improvement in skin manifestations was referred in 7 patients, a complete improvement in 4 patients, and a clinical stability was described in 1 case. There was 1 case in which a slight worsening was reported.

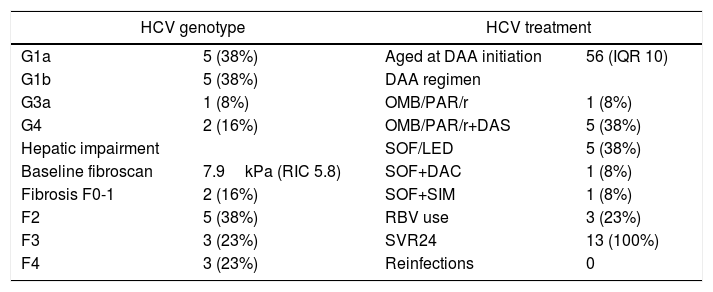

Table 4 shows virologic, hepatic fibrosis and HCV treatment information.

HCV: virologic, hepatic impairment and treatment parameters.

| HCV genotype | HCV treatment | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| G1a | 5 (38%) | Aged at DAA initiation | 56 (IQR 10) |

| G1b | 5 (38%) | DAA regimen | |

| G3a | 1 (8%) | OMB/PAR/r | 1 (8%) |

| G4 | 2 (16%) | OMB/PAR/r+DAS | 5 (38%) |

| Hepatic impairment | SOF/LED | 5 (38%) | |

| Baseline fibroscan | 7.9kPa (RIC 5.8) | SOF+DAC | 1 (8%) |

| Fibrosis F0-1 | 2 (16%) | SOF+SIM | 1 (8%) |

| F2 | 5 (38%) | RBV use | 3 (23%) |

| F3 | 3 (23%) | SVR24 | 13 (100%) |

| F4 | 3 (23%) | Reinfections | 0 |

HCV (hepatitis C virus), DAA (direct acting antivirals), OMB (ombitasvir), PAR (paritaprevir), r (ritonavir), DAS (dasabuvir), SOF (sofosbuvir), LED (ledipasvir), DAC (daclatasvir), SIM (simeprevir), RBV (ribavirine), SVR (sustained virologic response).

Fig. 1 shows graphically the clinical evolution and the key events in the PCT of the patients. All patients received DAA treatment between May 2015 and October 2016. A complete normalization of skin lesions was observed in 11 patients (84%) during the first 12 weeks after finishing their DAA treatment. Only 1 patient – HLP09 – suffered a worsening of his skin lesions after PCT specific treatment, improving totally soon after DAA initiation. One patient – HLP12 – developed cutaneous lessons that were not compatible with PCT after SVR. Urinary porphyrins in all 9 tested patients (included HLP12) returned to normal values. PCT specific therapy was subsequently stopped in the 4 patients who were still receiving it.

DiscussionOur observational study collects the biggest multidisciplinary series of cases until the date. It shows a completely favourable homogeneous clinical and analytical behaviour among HCV patients, even when coinfected with HIV. These results are consistent with the clinical cases previously referred in literature.9–14

Most of our sample consisted of males with a former IDU habit, since this risk behaviour is prevalently present in HCV patients in our area. Comparatively, the proportion of MSM in our PCT series was minimal which may be explained because of the actual highest HCV incidence among MSM with HIV on clinical follow-up. HCV incidence is currently higher among MSM with HIV, and frequent testing for this event in this population results in a shorter period since HCV infection to DAA use, allowing little time for PCT skin manifestations to appear (supposing UROD activity as normal). Beyond HCV and smoking (smoking was extremely very frequent in our patients), the other classical factors associated with PCT were barely present (HBP and DL are rare, no case of DM).

PCT diagnosis was performed, on average, 6 years before HCV DAA treatment. Some patients even had been diagnosed with PCT much earlier than HCV diagnosis. The clinical manifestations leading to PCT diagnosis were the classical described skin symptoms; these are blisters in photo exposed areas evolving to scars and hypertrichosis (the last condition was rare, but our high male prevalence induces us to believe this may be underreported). Definite PCT diagnosis was achieved after skin biopsy and urinary porphyrins testing. Although we have information about only 8 out of 13 patients, all 8 had urinary porphyrin levels far above over normal values (both for uroporphyrin and for coproporphyrin levels). Unluckily the remaining 5 patients’ data was not available during the retrospective research.

One out of the 11 patients tested for UROD activity showed a significant reduction in this enzyme activity, which in turn, led us to the presence of a polymorphism in this gene: 1 out of 11 patients analyzed had a type II PCT. This prevalence is not such different from the 20% referred in other series, considering that the prevalence for UROD dysfunction follows a north-south descending gradient. Beyond that, polymorphisms in HFE gene have shown some relevant data: 2 patients were heterozygous for both the C282Y and H63D loci and this is conclusive for HH diagnosis. Despite of this genetic information, this patient has never developed any HH clinical manifestation probably because of previous phlebotomies for PCT treatment. Other 5 patients had an isolated heterozygous condition and 1 was homozygous in the H63D loci. These H63D isolated polymorphisms are not enough to lead to an HH but the prevalence of these polymorphisms among our patients is definitively higher than the prevalence in general population: 73% (8 out of 11) vs. less than 40%.15,16 This reveals an association between H63D polymorphism and PCT in chronically infected patients for HCV which may be clarified by future analytical studies.

PCT treatment was chosen, according to the available guideline recommendations, with phlebotomies, chloroquine or a combination of both. After this PCT nonspecific treatment there was an improvement in almost all patients, with one remaining with skin lesions. It was observed the emergence of atypical skin lesions in one patient after achieving clinical resolution with a previous PCT treatment, but these manifestations were defined as not consistent with PCT and urinary porphyrin analysis was negative. This case shows the relevance of corroborating UROD activity normalization by determining urinary porphyrins, as we could testify some clinical controversial events which would make difficult to evaluate the PCT resolution without the porphyrins test in urine.

The biochemical analysis shows an initial high aminotransferase level which partially improved after PCT treatments (phlebotomies-chloroquine), and later reached to normal levels after HCV elimination. This is an interesting fact, as an improvement in hepatic damage markers was already evident after PCT specific treatment. This highlights the hepatotoxic effect of iron overload in PCT pathophysiology even without HH, which seems to be complementary to HCV hepatotoxic properties in these patients.16,17

Concerning to HCV infection, the most prevalent HCV genotypes were G1a and G1b, as it is expected in our area. G4 (2 patients) appeared exclusively in co-infected patients. HCV IFN-free DAA regimens reached SVR in all our patients, without any incident among the 5 patients with advanced hepatic fibrosis. This reflects a homogeneous response to DAA regimens although a specific analysis for every DAA regimen is not feasible. Interestingly, we found no reinfections in our patients during the referred follow-up.

In our series, all the analyzed patients (9 out of 9), including the one patient with type II PCT, normalized the urinary porphyrins after HCV elimination. This highlights that PCT was cured after HCV elimination, and was consistently associated with the remission of skin lesions when they were still present. If this evidence is confirmed, we could state that PCT associated to HCV is cured after HCV elimination. Besides of that, we could consider the futility of porphyrin determination after SVR is achieved in these patients. Urinary porphyrins after SVR would then be reserved only for cases with remaining or rebounding skin lesions.

Finally, although a case series is not a suitable design to stablish association or causality, we insist on the systematic review of the HIV-HCV coinfected patients belonging to the Infectious Diseases Unit. This enhances the possibility to state provisional generalizations from our series. Another limitation would be the retrospective design of our study, which has resulted in some lost data. This could be considered our main handicap, which is difficult to repair at this moment. At last, the fact that of our sample comprises both HCV mono-infected and HIV-HCV coinfected patients could be a limitation as well, but we think that this does not negatively impact our findings since the results observed in both groups were identical.

As I said, our study is one of the largest series of HCV-associated PCT referred to DAA use. Our main strength is that all our patients had a homogenous response to DAA HCV treatment, always followed by clinical and analytical PCT resolution. This aspect would be hardly attributed to bias or chance and considering the causality criteria involved in the clinical observations (temporary sequence, strong association, biological plausibility and specificity) we can conclude that PCT associated to HCV infection resolves after HCV eradication with DAA. In order to confirm our statement this data should be validated in other geographically different settings.

ConclusionsIn conclusion, the association between PCT (rare despite being the most frequent of porphyrias) with HCV infection is clear, especially in our HCV high prevalence geographic area, and clarifying whether HCV treatment modifies PCT evolution is still a question to be resolved.

Our series of cases is made of HCV mono-infected and HCV-HIV co-infected patients diagnosed with PCT before HCV eradication with DAA. HCV associated to PCT seems to have historically affected former IDU patients as they have been suffering HCV infection for a longer time than current HCV acutely infected MSM. Type I is widespread among our PCT patients, and PCT type II is anecdotal (as previously described in other studies). Its presentation is classically associated with HH: HFE polymorphisms for HH are expected to be more frequent among these patients, but surprisingly we observed that H63D loci (which is not enough to provoke HH when alone) could be associated with PCT as its prevalence in our sample is nearly twice of the expected in general population.

According to our data, SVR for HCV after use of DAA leads to PCT resolution. Despite our study limitations, HCV associated PCT resolves universally within our patients. Considering other series previously published in literature we could state that PCT resolution is almost guaranteed after HCV SVR. This cure for PCT is inferred by clinical normalization of symptoms and by analytical porphyrins normalization. Since PCT resolution after HCV SVR is constant within our series, it should lead to PCT specific treatment interruption without checking for urinary porphyrins (when there are no residual skin lesions) regardless of the degree of liver involvement, unless there is a different cause that could participate in the development of PCT. This statement is relevant for these PCT patients who are usually told to be lifelong adherent to chronic photoprotection and to chronic treatments, consequently resulting in a quality-of-life improvement.

Financial supportNone.

UnitsUnits are expressed on International Units System.

Conflict of interestNo conflict of interest to be declared.

I would like to express my gratitude to Dr. de los Santos and Dr. García-Buey for their support and dedication in this and other projects.