Errors are very common in daily clinical practice; however, they can be prevented. Our aim was to identify the most common errors in the outpatient management of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients.

Material and methodsPatients diagnosed with IBD, being treated at our IBD Unit and who were referred for a second opinion were consecutively enrolled. Data on the strategies implemented by their previous physicians were obtained. These strategies were compared with the currently recommended diagnostic and therapeutic procedures.

ResultsSeventy-four IBD patients were enrolled. Prior to care in our Unit, screening for tobacco use had been performed in 50% of Crohn's disease patients, while smoking cessation counselling had been provided in 29%. At the time of IBD diagnosis, the hepatitis B virus immunisation status had been investigated in 16% of the patients, the hepatitis C virus status in 15%, and the varicella status in 7%. Seven percent of the patients had been vaccinated against hepatitis B virus, and 3% against influenza, tetanus and pneumococcus. Sixty-seven percent of the patients with an indication for use of 5-aminosalicylic acid and 37% of those with an indication for immunosuppressants had received the indicated drug.

DiscussionErrors in the outpatient management of IBD patients are very common and relevant.

Los errores son muy comunes en la práctica clínica diaria; no obstante, pueden prevenirse. Nuestro objetivo fue identificar los errores más frecuentes en el manejo ambulatorio de los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII).

Material y métodosSe incluyeron pacientes consecutivos diagnosticados de EII atendidos en segunda opinión en nuestra Unidad de EII. Se obtuvieron datos sobre las estrategias que habían realizado los médicos que les atendieron previamente, y se compararon con los procedimientos diagnósticos y terapéuticos actualmente recomendados.

ResultadosSe incluyeron 74 pacientes. Previamente a la atención en nuestra Unidad, se había interrogado sobre el tabaquismo en el 50% de los pacientes con enfermedad de Crohn, y en el 29% se promocionó el abandono de este. Al diagnóstico de la EII, en el 16% se había evaluado la infección por el virus de la hepatitis B, en el 15% por el virus de la hepatitis C, y en el 7% por la varicela. El 7% de los pacientes había sido vacunado frente a la hepatitis B, mientras que el 3% frente a la gripe, tétanos y neumococo. El 67% y el 37% de los pacientes con indicación de 5-aminosalicitalos e inmunosupresores, respectivamente, los había recibido.

DiscusiónLos errores en el manejo de los pacientes ambulatorios diagnosticados de EII son muy frecuentes y relevantes.

Daily clinical practice involves constant decision making, and each decision is subject to possible error. Errors are very common in daily clinical practice; however, they can be prevented as has been shown in the field of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).1–3

Clinical practice guidelines are a tool of Evidence-Based Medicine, which provide a homogeneous framework for the diagnosis, therapeutic management and follow-up of patients based on the best scientific evidence available. In spite of these clinical practice guidelines for IBD and other areas of medicine, the level of follow-up of these recommendations is lower than expected and patients frequently receive sub-optimal care, with heterogeneous criteria not based on scientific evidence.4,5

Although sub-specialisation for a better efficacy in clinical practice is a need that is assumed, there are few studies to assess whether there is better quality healthcare when patients are cared for by doctors who focus specifically on IBD. Furthermore, the majority of studies that assess compliance with the recommendations based on scientific evidence are based on questionnaires inviting doctors to respond to the question as to what they would do, but few actually evaluate what doctors really do in their clinical practice by analysing their decisions as described in the patient's medical records.4–6 For all these reasons, the aim of this study was to identify different errors in the outpatient management of patients with IBD referred for a second opinion to the Integrated IBD Patient Care Unit of Hospital Universitario de La Princesa according to the clinical practice guidelines, in order to identify these errors and take measures intended to prevent them.

Material and methodsStudy designA retrospective, single-centre, cross-sectional study.

Study populationAll consecutive patients diagnosed with Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) treated in the Integrated IBD Patient Care Unit of Hospital Universitario de La Princesa, between June 2011 and June 2012, and who had previously had their IBD monitored by another doctor not belonging to our unit, were included.

Data collectionA specific questionnaire was designed to collect information on the follow-up of the patient prior to the start of their follow-up in our IBD unit. The questionnaire was completed by the two IBD specialists in our unit at the patient's first visit. The clinical data contained in the medical record documents provided by the patient were collected in the questionnaire. For those aspects for which no data existed in the clinical documents, the corresponding information was obtained from the interview with the patient at the time of the consultation.

The data collected consisted of demographic data, IBD data (type, extension, phenotype, year of diagnosis), area of specialisation of the patient's referring doctor, smoking history prior to diagnosis, and information regarding the prior study of the patient's immunological status with respect to hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and chickenpox, in addition to the administration of vaccines in the cases recommended. Furthermore, information was collected regarding the treatments received previously by patients: indication, route of administration and dose of 5-aminosalicylic acid (5-ASA), corticosteroids and immunosuppressants. It was also checked whether the patient had been included in a colorectal cancer (CRC) screening programme due to their IBD, if indicated. Data were recorded relating to the attitude of the previous doctor if the patient had presented a flare-up of their disease and it was determined whether an enteric infection had been ruled out during the flare-up.

DefinitionsThe reference standards for assessing the quality of care received by patients were the guidelines issued by the European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation (ECCO). In certain aspects where no recommendation exists in ECCO's consensuses, the best scientific evidence available was employed.

- a)

A previous adequate immunisation study: if on diagnosis of IBD an immunisation study of the patient against HBV, HCV, HIV and chickenpox had been requested and if carrying out a Mantoux test had been indicated. If any of these tests were lacking, it was considered that the study had been inadequate.

- b)

Adequate promotion of immunisation: if after determining that the patient did not have immunity against HBV, chickenpox, the influenza virus, tetanus or pneumococcus, the treating doctor had recommended that the patient be vaccinated.

- c)

Adequate extension study of the CD: it was considered that this had been adequate if after CD diagnosis an ileocolonoscopy and a magnetic resonance entero-colonography or an abdominal computer assisted tomography had been requested.

- d)

Adequate indication of treatment with 5-ASA, immunosuppressants and steroids: it was considered that treatment with these drugs had been adequate if the current ECCO recommendations had been followed for treatment of IBD patients with these drugs.7,8

- e)

Adequate prevention of osteoporosis: if the concomitant administration of calcium and vitamin D had been indicated in those patients who had been administered systemic steroid treatment.

- f)

Adequate CRC screening: CRC screening was adequate if the screening colonoscopy had been requested for patients with UC (except proctitis) or CD with colic affectation (at least 2 colon segments affected) of more than 8 years’ progression. Moreover, the frequency of screening colonoscopies was considered adequate if the current ECCO recommendations had been followed, once the risk to the patient had been stratified after the first screening colonoscopy.9

- g)

Adequate approach regarding IBD flare-ups: approach was considered adequate if given the clinical presence of a flare-up in a patient with IBD, the doctor had requested a bacteriological study in faeces (stool cultures and Clostridium difficile [C. difficile] toxin) to rule out enteric infection and if the presence of clinical activity had been confirmed by endoscopy or an imaging test.

The study was approved by the Clinical Research Ethics Committee of our centre and was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and good clinical practice guidelines.

Statistical analysisIn the statistical analysis, the quantitative variables were expressed as mean and standard deviation (if the variable followed a normal distribution) or as median and interquartile range (if it did not follow a normal distribution). The percentages for the qualitative variables, with their 95% confidence intervals were calculated. In the univariate study, the categorical variables were compared using the chi-squared (χ2) test. It was determined that a difference was statistically significant if the p value was <0.05.

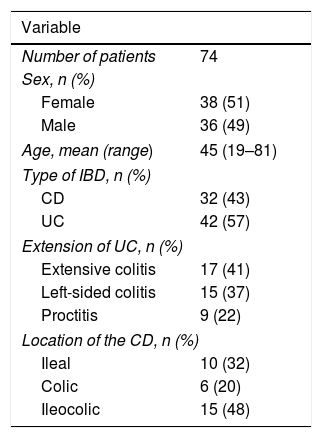

ResultsGeneral characteristics of the study populationA total of 74 patients were recruited. The demographic characteristics of the patients are summarised in Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the study population.

| Variable | |

|---|---|

| Number of patients | 74 |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 38 (51) |

| Male | 36 (49) |

| Age, mean (range) | 45 (19–81) |

| Type of IBD, n (%) | |

| CD | 32 (43) |

| UC | 42 (57) |

| Extension of UC, n (%) | |

| Extensive colitis | 17 (41) |

| Left-sided colitis | 15 (37) |

| Proctitis | 9 (22) |

| Location of the CD, n (%) | |

| Ileal | 10 (32) |

| Colic | 6 (20) |

| Ileocolic | 15 (48) |

CD, Crohn's disease; IBD, inflammatory bowel disease; UC, ulcerative colitis.

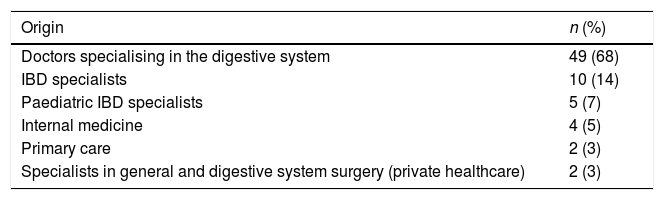

The majority of patients had been referred to our unit from digestive system specialists and other IBD specialists, as can be seen in Table 2. The median time from diagnosis to referral to our centre was 65 months.

Origin of the patients referred to our IBD unit.

| Origin | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Doctors specialising in the digestive system | 49 (68) |

| IBD specialists | 10 (14) |

| Paediatric IBD specialists | 5 (7) |

| Internal medicine | 4 (5) |

| Primary care | 2 (3) |

| Specialists in general and digestive system surgery (private healthcare) | 2 (3) |

IBD: inflammatory bowel disease.

Smoking had been investigated in 50% (95% CI 31–69) of patients with CD. A total of 36% (95% CI 18–57) of those patients had been informed of the negative effects of smoking on IBD and in 29% of these (95% CI 13–51) giving up smoking had been promoted.

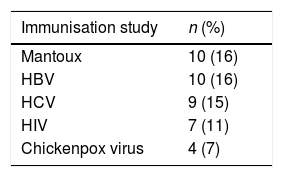

Immunisation study upon IBD diagnosisFor the majority of patients, an adequate immunisation study had not been performed upon IBD diagnosis. Table 3 summarises the immunisation study upon diagnosis.

Promotion of immunisationsThe HBV vaccine was administered to 7% of the non-immunised patients upon diagnosis and the chickenpox vaccine to 3% of the patients. Immunisation against pneumococcus and tetanus was promoted in 3% of patients who reported not being vaccinated. Vaccination against seasonal influenza was also recommended in 3% of patients.

Study of the location of the disease in patients with CDIn patients with CD, only the involvement of the small intestine was investigated in 7% of patients, while in another 7% of patients, only the presence of the disease in the colon was studied. Furthermore, in 86% (95% CI 66–96) of patients diagnosed with CD, it was investigated whether the disease affected the small intestine and the colon.

Treatment of IBDTreatment with 5-ASAOf those patients in whom treatment with 5-ASA was indicated (patients with at least left-sided ulcerative colitis), only 67% (95% CI 53–78) had received it. Of those who received 5-ASA, 93% (95% CI 80–98) were treated with an induction dose lower than that recommended, with the median dose of under-dosed patients being 2g (IQR 2–3). Some 85% (95% CI 70–94) received a fractionated dose regimen (instead of once daily). A total of 31% of the patients had received a maintenance dose below that established, with the median maintenance dose of the under-dosed patients being 1.2g daily (IQR 1–2). Some 42% of the patients in whom treatment with oral 5-ASA was not indicated had received it (patients with diagnosis of Crohn's disease with involvement of the small intestine). A total of 41% of patients, for whom topical treatment with 5-ASA had been indicated, received it.

Treatment with steroidsA total of 53% (95% CI 29–75) of patients with ileal involvement and minor activity had received treatment with systemic corticosteroids (instead of budesonide) to induce remission; the rest of the patients were treated with oral budesonide. Moreover, 22% of patients received budesonide for more than three months.

Treatment with immunosuppressantsTreatment with immunosuppressants had been started in 38% (95% CI 19–59) of patients in whom this was indicated. A total of 29% of patients received the full dose of immunosuppressants (azathioprine or 6-mercaptopurine) from the start. The median of the dose of patients treated with azathioprine who were under-dosed was 1.2mg/kg every 24 h (IQR 1–1.8).

Prevention of osteoporosisSome 13% of patients who had received systemic steroids had taken calcium and vitamin D as osteoporosis prevention. Bone mineral density was assessed by densitometry in 12% of the patients who had received prolonged corticosteroid therapy.

Colorectal cancer screeningColorectal cancer screening had been started in 56% (95% CI 30–80) of those patients with indication; of these, the screening was started at the appropriate time in 33% of patients, and in 38% the colonoscopies were repeated with the recommended frequency.

Attitude towards flare-ups of the diseaseIn 90% (95% CI 55–99) of patients, the presence of clinical activity was confirmed by performing an endoscopy or imaging tests. In 75% (95% CI 43–97) of cases of IBD activity, stool cultures and parasites in stools were requested, meanwhile in 70% (95% CI 35–93) of patients with IBD activity, the presence of the C. difficile toxin in stools was investigated.

Response of general digestive health physicians vs IBD specialistsIBD specialists carried out a more adequate promotion of immunisation among patients who had not been vaccinated against HBV, pneumococcus, chickenpox and tetanus, compared with general digestive health physicians and this difference was statistically significant.

No statistically significant differences were found in the response of the IBD specialists vs the general digestive health physicians with respect to the smoking study in patients with CD, the promotion of stopping smoking in these patients, the immunisation study upon diagnosis, the study of the CD location upon diagnosis of the disease, the indication and adequate dosing of both the induction and maintenance dose of 5-ASA, the indication of treatment with steroids and immunosuppressants, the prevention of osteoporosis in patients receiving treatment with steroids, CRC screening or in their attitude towards the presence of IBD activity.

DiscussionThis study demonstrates that errors in the outpatient care of patients with IBD are common, in spite of the fact that the vast majority of the patients were referred to our unit by digestive system specialists. This is in line with other studies published, which have shown that the response of general digestive health physicians differs from current recommendations based on scientific evidence in up to 30% of cases.4

In our study, only half of the previous doctors asked patients with CD about their smoking habit and less than one third promoted quitting smoking. Nulsen et al. investigated the knowledge, attitudes and practices of 140 gastroenterologists with respect to smoking among their patients with CD. The authors observed that 66% of the gastroenterologists asked their patients about smoking and only one third of these promoted quitting smoking.10 In other studies, around 90% of gastroenterologists investigated whether their patients with CD were smokers.11,12 However, it should be remembered that in these studies, the electronic medical records included a warning to remind the doctor to screen for smoking.

The ECCO recommends assessing the immunisation status of patients with IBD at the time of diagnosis and the administration of the appropriate vaccines to avoid preventable infections.13 According to our results, an adequate study of immunisation status at the time of IBD diagnosis was performed in less than 20% of patients. In this aspect, we found no differences between IBD specialists and general digestive health physicians. These results are in line with other studies published in which the frequency of the study of the immunological status of patients with IBD by doctors was between 14% and 40%.14–17

According to our study, in the vast majority of patients, vaccination against HBV, chickenpox, seasonal influenza, pneumococcus or tetanus was not given. However, the IBD specialists recommended vaccination in patients who were not immunised more often compared with general digestive health physicians. This data is in line with the results from other studies.14 The low rate of vaccination among our patients suggests that both general digestive health physicians and IBD specialists are not recommending the vaccinations indicated for patients with IBD with the necessary frequency. In a study published by Wasan et al., 22% of the 167 IBD patients surveyed had refused to be vaccinated in the past. Of these, 14% reported that their doctors had told them that immunisation was not necessary.18 Another study that included 198 IBD specialists found that only 23% of them investigated the immunisation status of their patients. The authors concluded that these findings could be due to different factors, such as the doctors’ lack of knowledge, the indifference of both the doctors and the patients or concern regarding the possible side effects of the vaccines.17

The combined treatment with oral and topical 5-ASA demonstrated its superiority for the induction and maintenance of remission in patients with UC compared with oral 5-ASA in monotherapy.19 Of note in our study is the significant proportion of patients for whom treatment with oral 5-ASA is indicated who had not received it and the frequency of under-dosing in cases where treatment with 5-ASA was indicated. However, almost half of the patients for whom treatment with 5-ASA was not indicated, due to them being patients with CD with small intestine involvement, had received this treatment. An explanation of these facts would be the lack of knowledge of the guidelines regarding which IBD patients should receive treatment with 5-ASA and the adequate dose. In spite of the current recommendations, in our study only 41% of patients in whom topical treatment during the flare-up of the disease is indicated received said treatment. Another common error that came to light in our study was that more than 85% of patients received a fractionated dose of oral 5-ASA, in spite of the fact that this is one of the main factors associated with lack of treatment adherence, as has been demonstrated in various studies.20

Thiopurines are the first-choice drug in corticodependent patients with CD and UC.1 According to our results, of the total number of patients who received immunosuppressants, treatment with these drugs was only indicated for 38%. These results are in contrast to another study in which 86% of the 285 gastroenterologists surveyed stated that azathioprine was always indicated in cortico-refractory or corticodependent patients.14 This could be explained because our study is based on real clinical practice and knowledge of clinical practice guidelines does not always guarantee their application.

In our study, CRC screening had already commenced in just over half of IBD patients for whom this was indicated. Of these, the screening had started at the adequate time in only one third and colonoscopies were repeated with the recommended frequency in just over one third of patients. Similar results were published by Vershuren et al.15 The authors found that doctors initiated CRC screening at eight to ten years from diagnosis in 57% of patients with left-sided colitis and in 70% of patients with extensive colitis at eight to ten years from diagnosis. Furthermore, the frequency of monitoring colonoscopies was inadequate in 80% of cases.

According to our results, there were no statistically significant differences in the different responses of the IBD specialists compared with the general digestive health physicians, except for the vaccination of non-immunised patients. In both groups, the frequency of errors in routine clinical practice was very high. An explanation for this fact could be the relatively small number of patients included in our study, above all in the group of patients referred to our unit by IBD specialists.

The variability in clinical practice may be due to different causes: lack of knowledge regarding the efficacy of certain drugs, beliefs regarding the cost of treatment or of the safety profiles of the drugs.21 Another possible explanation would be the lack of knowledge of the existence of clinical practice guidelines, as has been observed in other studies.22

This study has some relevant limitations. Firstly, it is a retrospective study. Therefore, a possible recall bias should be taken into account. Although a careful and exhaustive review was carried out of the patients’ medical records and a standardised questionnaire was administered with the aim of minimising this bias, it is clear that additional prospective studies are needed which would allow for a more precise identification of the areas for improvement that our study has uncovered and specific measures to be taken to improve compliance with clinical practice guidelines. Secondly, there could be a selection bias, since the study population included patients referred to our unit for a second opinion and the previous approach received by these patients could have been of a lower quality than those patients who had not been referred. Thirdly, the study design is single-centre and the number of patients included is relatively small. Therefore, some results may not be representative. Furthermore, the fact that the median follow up is 65 months and that the adaptation to current guidelines was assessed retrospectively could have influenced the results of poor compliance with the recommendations; however, the recommendations assessed in this study have not undergone substantial variation in recent years.

However, our study has the strength of being one of the few studies to assess the routine clinical practice in patients referred to an IBD unit, comparing it with currently recommended procedures, since, unlike other studies, ours is not limited to simply administering a questionnaire asking the doctor what they would do, but evaluates what the doctor really does in their clinical practice by analysing their decisions as described in the patient's medical records.

In conclusion, this study demonstrates that the errors made in the management of outpatients diagnosed with IBD are very common, both among general digestive health physicians and IBD specialists. The most common errors made were in the study of the patient's immunisation status and in the indications and doses of treatment with 5-ASA and immunosuppressants. These findings justify the need for a greater dissemination of the clinical practice guidelines among gastroenterologists and continuous training activities supported by scientific societies. This dissemination could be carried out by means of training sessions and courses organised by these societies, both by classroom attendance and online means. Finally, our results reinforce the recommendation that patients with IBD should undergo follow-up for their condition in specialist and accredited units.

FundingGETECCU-ABBOTT grant from Theory to Practice 2010–2011.

Conflicts of interestM.J. Casanova: has received funding to attend congresses and to participate in training activities with Pfizer, Janssen, MSD, Ferring, AbbVie.

M. Chaparro: given scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities with MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Takeda, Janssen.

J.P. Gisbert: given scientific advice, support for research and/or training activities: MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

Please cite this article as: Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, Gisbert JP. Errores en la atención de los pacientes con enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal: estudio «ERRATA». Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;43:233–239.