Tofacitinib is an oral synthetic small-molecule inhibitor of Janus kinases, which are involved in the pathogenesis of various inflammatory diseases, representing a new therapeutic option for ulcerative colitis. The efficacy and safety of tofacitinib have been demonstrated in clinical trials in patients with moderate to severe ulcerative colitis, and it has recently been approved by the European Medicines Agency to treat this disease. This article reviews the most relevant characteristics of tofacitinib, its main differences from biological agents, the studies which demonstrate its efficacy in patients with ulcerative colitis, and its optimal use in different clinical situations.

Tofacitinib es una molécula pequeña sintética, de administración oral, que actúa inhibiendo a las cinasas Janus implicadas en la patogénesis de diversas enfermedades inflamatorias, y constituye una nueva opción terapéutica para la colitis ulcerosa. La eficacia y la seguridad de tofacitinib en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa activa de moderada a grave han quedado demostradas en ensayos clínicos y este fármaco ha sido recientemente aprobado por la Agencia Europea de Medicamentos para el tratamiento de dicha enfermedad. En el presente artículo se revisan las características más destacadas de tofacitinib, sus principales diferencias con los tratamientos biológicos, los estudios que demuestran su eficacia en pacientes con colitis ulcerosa y su optimización en diferentes situaciones clínicas.

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that affects the colonic mucosa and is characterised by alternating periods of activity and remission. Its pathogenesis is multi-factorial; factors include genetic predisposition, mucosal barrier defects, immune response regulation disorders, intestinal microbiota and environmental factors.1 Its incidence is on the rise, and it has a higher prevalence in developed countries.2,3

The aim of short-term treatment of active UC is to manage the signs and symptoms of the disease (induction treatment). Once this is achieved, the aim of long-term treatment is to prevent new disease flare-ups (maintenance treatment). Both stages of treatment are intended to act on the disease process and reduce inflammation of the colonic mucosa.1 Treatment options in UC (amino salicylates, corticosteroids, azathioprine/mercaptopurine, cyclosporine and biologic drugs) are not effective for all patients; therefore, medical needs that are not met by induction and maintenance therapies persist.4 At present, amino salicylates are the first-line treatment for induction and maintenance of remission in mild to moderate UC; corticosteroids are indicated when patients do not respond to amino salicylates and in patients with moderate or severe activity; and immunosuppressants and biologic drugs are used in moderate to severe UC that does not respond to treatment with corticosteroids or is corticosteroid-dependent. With the availability of these drug treatments, the need for surgical treatment has decreased in the last few decades, although the colectomy rate remains relatively high (3–17% 10 years after diagnosis).5,6

In recent years, the incorporation of biologic drugs (infliximab, adalimumab, golimumab and vedolizumab) into clinical practice has represented an improvement in the treatment of moderate to severe UC.7,8 These drugs are monoclonal antibodies that act on cytokines or integrins, that is to say, on extracellular molecules or on the cell membrane. Recently, new active substances have been developed for various diseases. These new active substances are classified as small-molecule drugs. Some of them, filgotinib, upadacitinib, peficitinib, TD1473, Pf-06651600, Pf-06700841, ozanimod and etrasimod, are currently in different stages of development for the indication of Crohn's disease and/or UC.9 They consist of small molecules that act on signal transduction within cells or modulate immune cell traffic. These drugs include tofacitinib, a Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitor.10 It was approved in 2012 by the Food and Drug Administration and in 2017 by the European Medicines Agency and the Spanish Medicines Agency for the treatment of moderate to severe active rheumatoid arthritis.11 In 2018, tofacitinib (Xeljanz®) in combination with methotrexate gained authorisation from the European Medicines Agency for the treatment of active psoriatic arthritis in adult patients who have had an inadequate response to or could not tolerate prior treatment with a disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drug and for the treatment of UC in patients with active moderate to severe disease who had an inadequate response, loss of response or intolerance to conventional treatment or a biologic drug.11 The objective of this article is to review current knowledge of the efficacy of tofacitinib in the treatment of UC, as well as the main differences between tofacitinib and biologic treatments and strategies for optimisation in different clinical situations.

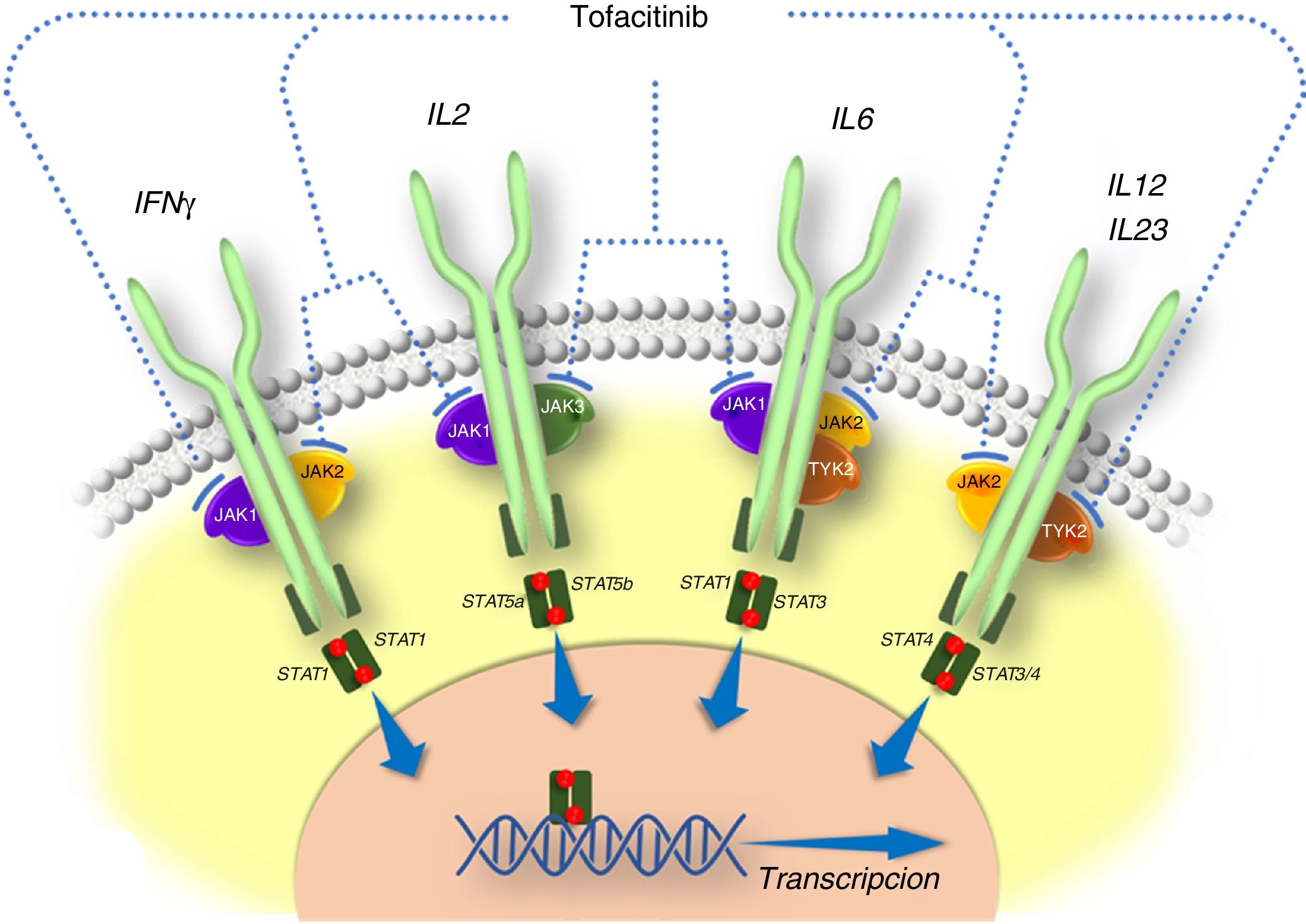

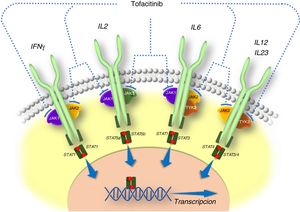

General information on tofacitinibThe pathogenesis of IBD and other inflammatory diseases involves various cytokines that act by activating JAKs. JAKs comprise a family of intracellular tyrosine kinase enzymes that phosphorylate tyrosine hydroxyl residues in their target proteins and modify their activity. They include the enzymes JAK1, JAK2, JAK3 and tyrosine kinase 2 (TYK2). Whereas kinases JAK1, JAK2 and TYK2 are ubiquitous, JAK3 is found predominantly in haematopoietic cells. JAKs are activated by many cytokines, such as interleukins and interferons, and by hormones such as erythropoietin, thrombopoietin and growth hormone.10 The binding of a cytokine to its receptor induces activation of JAKs associated with that receptor and ultimately causes phosphorylation of signal transducers and activators of transcription (STATs), that is to say, STAT activation. Phosphorylated STAT dimers are translocated to the nucleus, where they play a role in regulating the expression of hundreds of proteins that participate in immune response and contribute to inflammation.10

Tofacitinib is a small-sized synthetic drug that primarily inhibits JAK3 and JAK1, and to a lesser extent inhibits JAK2 and TYK2.12 It binds selectively and reversibly to the adenosine triphosphate (ATP) binding site in the kinase. This action blocks the signal transduction of the receptors of several interleukins (IL-2, IL-4, IL-6, IL-7, IL-15 and IL-21) and type I and II interferons, thereby modulating the inflammatory and immune response.12,13 Therefore, its mechanism of action in UC consists of inhibiting several cytokines that are linked to the pathogenesis of the disease14,15 (Fig. 1).

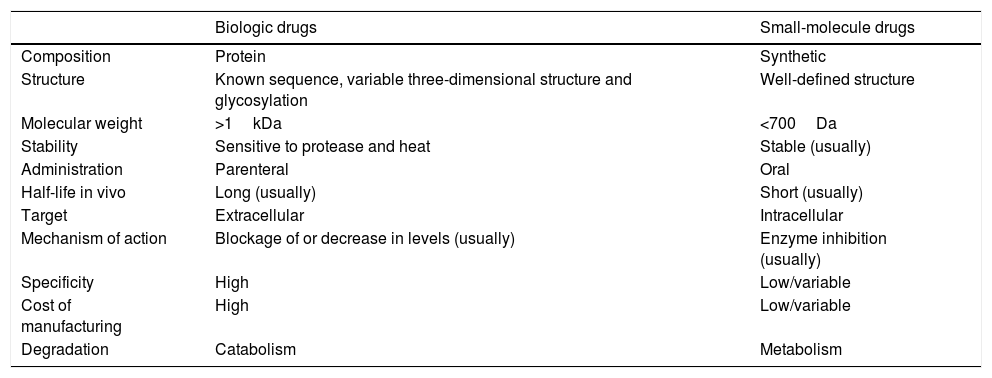

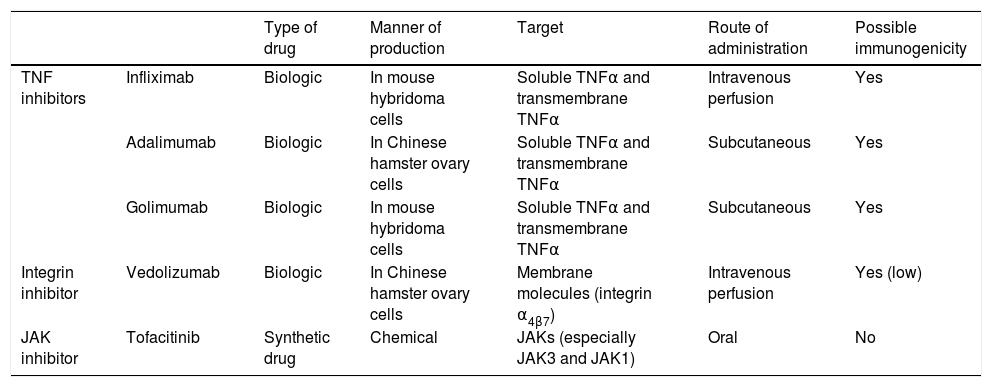

Advances in knowledge of the inflammatory cascade, as well as the role of cytokines and adhesion molecules in the pathogenesis of IBD, have led to the development of biologic drugs that are effective in UC. At present, three tumour necrosis factor (TNF) inhibitor drugs (infliximab, adalimumab and golimumab) and one drug that targets integrin α4β7 (vedolizumab) are approved. These biologic agents are monoclonal antibodies and their production requires live cells; they are not synthesised by means of chemical procedures. In addition, as they are proteins, they can induce immunogenicity. The most significant differences between biologic drugs and so-called small-molecule drugs are summarised in Table 1.

Differential characteristics of biologic drugs and small-molecule drugs.

| Biologic drugs | Small-molecule drugs | |

|---|---|---|

| Composition | Protein | Synthetic |

| Structure | Known sequence, variable three-dimensional structure and glycosylation | Well-defined structure |

| Molecular weight | >1kDa | <700Da |

| Stability | Sensitive to protease and heat | Stable (usually) |

| Administration | Parenteral | Oral |

| Half-life in vivo | Long (usually) | Short (usually) |

| Target | Extracellular | Intracellular |

| Mechanism of action | Blockage of or decrease in levels (usually) | Enzyme inhibition (usually) |

| Specificity | High | Low/variable |

| Cost of manufacturing | High | Low/variable |

| Degradation | Catabolism | Metabolism |

Source: Danese et al.4

Although the efficacy of TNF inhibitor drugs is beyond question, up to 30% of patients do not initially respond to treatment (primary failure)16 and up to 50% may experience loss of response over time (secondary failure).17 In addition, serum levels of a TNF inhibitor drug before the drug is administered again appear to determine clinical outcomes in UC, at least in part, as an increased risk of colectomy has been shown when serum levels of infliximab are low or cannot be detected.18 Therefore, it has been suggested that monitoring plasma levels of the biologic agent and antidrug antibodies could be useful for dose optimisation.19–21 By contrast, in studies conducted with tofacitinib in patients with UC, no loss of efficacy due to a drop in mean plasma levels of tofacitinib has been seen.22 Tofacitinib acts rapidly, and the pharmacokinetic data do not suggest any reduction of serum levels when treatment duration is prolonged22,23; this drug is seen to exhibit clinical efficacy 2–8 weeks after the start of treatment.22,24 Moreover, the therapeutic effect of biologic treatments is linked to the levels reached, such that there is a great deal of inter-individual variability in terms of pharmacokinetics; therefore, it has been suggested that it is appropriate to monitor these levels to optimise treatment.24

Finally, vedolizumab, a humanised monocolonal antibody that binds specifically to integrin α4β7, presents the same principles of pharmacokinetics as TNF inhibitor drugs.25 Antibodies against this drug have also been detected, though they are less common than antibodies against TNF inhibitor drugs.21

Table 2 sums up the main differences between biologic drugs and JAK inhibitors that have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of UC with respect to manner of production, therapeutic target, route of administration and potential for immunogenicity.

Main differences between biologic drugs and Janus kinase (JAK) inhibitors that have demonstrated efficacy in the treatment of ulcerative colitis.

| Type of drug | Manner of production | Target | Route of administration | Possible immunogenicity | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF inhibitors | Infliximab | Biologic | In mouse hybridoma cells | Soluble TNFα and transmembrane TNFα | Intravenous perfusion | Yes |

| Adalimumab | Biologic | In Chinese hamster ovary cells | Soluble TNFα and transmembrane TNFα | Subcutaneous | Yes | |

| Golimumab | Biologic | In mouse hybridoma cells | Soluble TNFα and transmembrane TNFα | Subcutaneous | Yes | |

| Integrin inhibitor | Vedolizumab | Biologic | In Chinese hamster ovary cells | Membrane molecules (integrin α4β7) | Intravenous perfusion | Yes (low) |

| JAK inhibitor | Tofacitinib | Synthetic drug | Chemical | JAKs (especially JAK3 and JAK1) | Oral | No |

The development of JAK inhibitors such as tofacitinib represents a new approach to the treatment of immune-mediated inflammatory diseases. The fact that they have a rapid pharmacological effect in an oral formulation renders them particularly appealing. Moreover, JAK/STAT signalling pathway inhibitors are capable of blocking multiple cytokines at the same time. However, both TNF inhibitor biologic drugs and anti-integrin drugs are meant to inhibit a single component of the inflammatory response. Inhibition of a single cytokine may not be enough to completely resolve the gut's inflammatory response, which is regulated by multiple cytokines. On the other hand, simultaneous inhibition of several pro-inflammatory pathways would, at least in theory, allow for more extensive resolution of the intestine's inflammatory response, even though inhibition of the different components of the inflammatory cascade is not normally complete.9

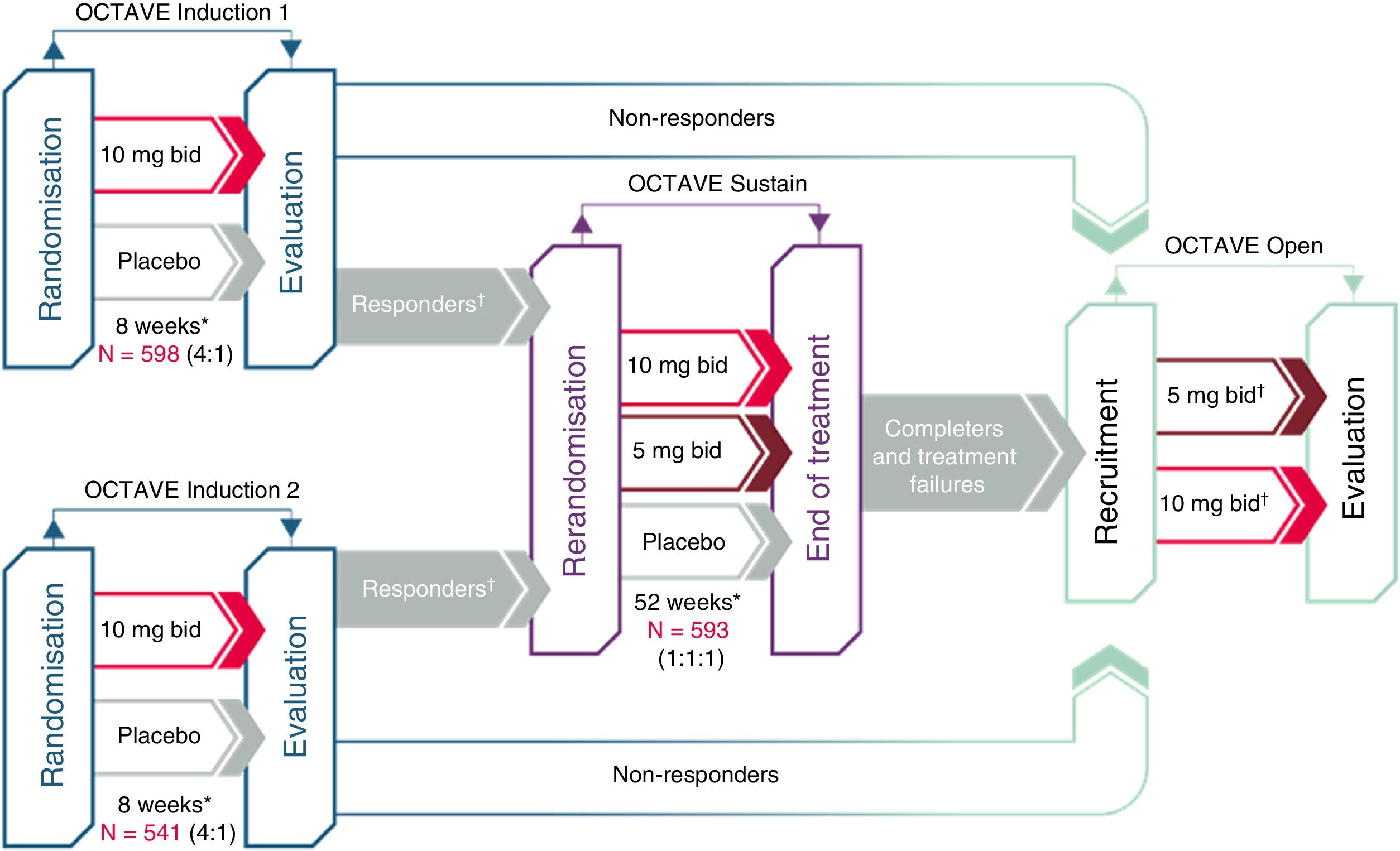

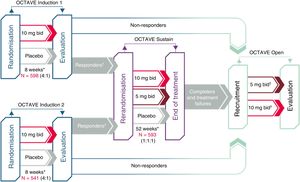

Clinical development of tofacitinib in ulcerative colitisThe efficacy of tofacitinib has been evaluated in one phase-2 and three phase-3 clinical trials in patients with moderate to severe UC (Fig. 2). The most outstanding aspects of these studies are reviewed below.

Clinical development of tofacitinib in ulcerative colitis.

*Final evaluation of complete efficacy in week 8/52. Continuous treatment up to week 9/53.

†“Responders” are patients who achieved clinical response during the OCTAVE Induction 1 or 2 study.

‡Patients in remission at week 52 of the OCTAVE Sustain study were assigned to tofacitinib 5mg/12h; patients who completed 8 weeks of treatment in the OCTAVE Induction 1 or 2 study and were classified as non-responders as well as patients who completed the OCTAVE Sustain study but did not meet the requirements for remission or left the study early due to treatment failure were assigned to tofacitinib 10mg/12h.

First, a phase-2 clinical trial was conducted. This was a multi-centre, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with several doses of tofacitinib.26 It enrolled 194 patients, who were randomised (2:2:2:3:3) to receive 0.5, 3, 10 or 15mg or tofacitinib or placebo, twice daily, for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical response in week 8 evaluated using the Mayo score, which includes number of bowel movements, presence of blood in stool, the physician global assessment of the patient's status and endoscopic lesions. The secondary efficacy endpoints included clinical remission, endoscopic response and endoscopic remission at 8 weeks. In addition, health-related quality of life (HRQoL) was measured with the Inflammatory Bowel Disease Questionnaire (IBDQ).

After that, the OCTAVE Induction 1 and 2 studies as well as two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase-3 clinical trials that were identical in design were conducted.22 They enrolled 598 and 541 patients, respectively, who had moderate to severe active UC despite prior conventional treatment or treatment with a TNF inhibitor drug. Patients received induction treatment with 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily or placebo for 8 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission in week 8.

The OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study22 enrolled 593 patients who had experienced a clinical response to induction treatment. These patients were randomised to receive maintenance treatment with tofacitinib (5 or 10mg twice daily) or placebo for 52 weeks. The primary endpoint was clinical remission in week 52.

Finally, OCTAVE Open, an open extension study, is under way. This is a multi-centre, open-label, uncontrolled phase-3 extension study. The main objective is to evaluate the long-term safety of tofacitinib at doses of 5 and 10mg twice daily in patients with moderate to severe active UC who have completed the OCTAVE Induction 1 and 2 studies and have not achieved clinical response or who completed or suspended treatment in the OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study. The secondary objectives are to evaluate long-term efficacy and quality of life.27

In the OCTAVE Induction and Sustain studies, clinical remission was defined as a total Mayo score ≤2, with no sub-score >1 and a sub-score for rectal bleeding of 0. It should be noted that this definition of remission is stricter than that used in prior studies with biologic drugs.22

During the induction studies, concomitant use of oral amino salicylates and oral corticosteroids was allowed. However, the use of TNF inhibitor drugs, azathioprine/mercaptopurine or methotrexate was not allowed. Moreover, in the maintenance trial, concomitant use of oral corticosteroids was allowed, although gradual dose reduction to the point of suspension was required.

Clinical efficacy of tofacitinib in ulcerative colitisFirst of all, when analysing the clinical efficacy of tofacitinib, it is important to bear in mind that the patients enrolled in the OCTAVE Induction 1 and 2 clinical trials had relatively severe UC: their mean disease duration was 8.1 years, 51% of them had extensive colitis or pancolitis, their mean Mayo score was 9.0, 52% of them had previously experienced treatment failure with TNF inhibitor drugs and 46% were receiving corticosteroids at the start of the study with tofacitinib.28

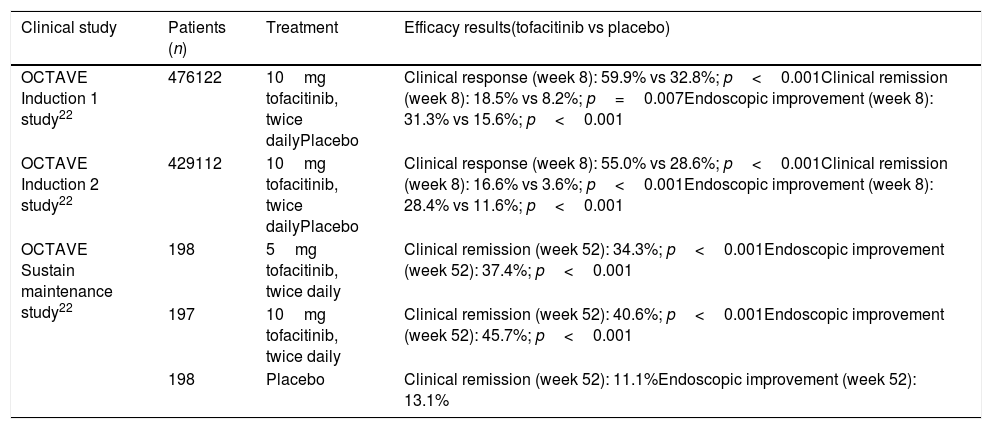

The phase-3 clinical trials confirmed the superiority of tofacitinib over placebo in induction treatment and in maintenance of clinical remission in patients with moderate to severe UC, as shown in Table 3.

Efficacy results in clinical trials with tofacitinib in patients with ulcerative colitis.

| Clinical study | Patients (n) | Treatment | Efficacy results(tofacitinib vs placebo) |

|---|---|---|---|

| OCTAVE Induction 1 study22 | 476122 | 10mg tofacitinib, twice dailyPlacebo | Clinical response (week 8): 59.9% vs 32.8%; p<0.001Clinical remission (week 8): 18.5% vs 8.2%; p=0.007Endoscopic improvement (week 8): 31.3% vs 15.6%; p<0.001 |

| OCTAVE Induction 2 study22 | 429112 | 10mg tofacitinib, twice dailyPlacebo | Clinical response (week 8): 55.0% vs 28.6%; p<0.001Clinical remission (week 8): 16.6% vs 3.6%; p<0.001Endoscopic improvement (week 8): 28.4% vs 11.6%; p<0.001 |

| OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study22 | 198 | 5mg tofacitinib, twice daily | Clinical remission (week 52): 34.3%; p<0.001Endoscopic improvement (week 52): 37.4%; p<0.001 |

| 197 | 10mg tofacitinib, twice daily | Clinical remission (week 52): 40.6%; p<0.001Endoscopic improvement (week 52): 45.7%; p<0.001 | |

| 198 | Placebo | Clinical remission (week 52): 11.1%Endoscopic improvement (week 52): 13.1% |

Clinical remission: total Mayo score ≤2, with no sub-score >1 and a sub-score for rectal bleeding of 0. Endoscopic improvement: Mayo endoscopic sub-score 0–1. Clinical response: reduction from baseline Mayo score ≥3 points and ≥30% accompanied by a reduction of the sub-score for rectal bleeding by at least 1 point or an absolute score for rectal bleeding of 0–1.

The OCTAVE Induction 1 study found clinical remission at 8 weeks in 18.5% of patients treated with tofacitinib versus 8.2% in the placebo group (p=0.007). The OCTAVE Induction 2 study showed remission at 8 weeks in 16.6% of patients treated with tofacitinib versus 3.6% in the placebo group (p<0.001).22

In a post hoc analysis of the Induction 1 and 2 studies, tofacitinib showed a rapid onset of action, with significant improvement in UC symptoms 3 days after administration.23 Improvements were also seen in the partial Mayo score (excluding the endoscopy component) (p<0.001) and in the physician global assessment (p<0.01) two weeks after the start of treatment (first study evaluation), with a maximum drop in CRP towards the fourth week of treatment (first time evaluated after the start of treatment).22 This beneficial effect was seen in both patients who had not previously received TNF inhibitor drug treatment and those in whom this treatment had failed.23 Therefore, unlike other, slower-acting drugs (such as vedolizumab), the introduction of concomitant treatment with steroids has not been proposed in patients who do not receive them at the start of treatment.

Efficacy of tofacitinib in maintenance of remission of ulcerative colitisIn the OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study, clinical remission was demonstrated at 52 weeks in 34.3% of patients treated with 5mg of tofacitinib twice daily and in 40.6% of those who received 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily, versus 11.1% of the placebo group (p<0.001, for both 5 and 10mg).22

One of the secondary endpoints in the OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study was sustained remission at 52 weeks without concomitant treatment with corticosteroids. In the patients who were in clinical remission when they were enrolled in the study, remission was maintained without using corticosteroids in a higher percentage of patients treated with tofacitinib: in 35.4% of those treated with 5mg of tofacitinib twice daily and in 47.3% of those who received 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily, versus 5.1% of the placebo group (p<0.001).22

In addition, the percentage of remission without corticosteroids among patients who received these drugs at the start of the study was 27.7% in those treated with 5mg of tofacitinib, 27.6% in those treated with 10mg of tofacitinib and 10.9% in those who received placebo (p<0.05).11

Long-term maintenance was evaluated in month 12 of the OCTAVE Open study. A total of 73.8% of the patients who achieved remission at the end of the OCTAVE Sustain study (at 52 weeks) by taking tofacitinib 5 or 10mg twice daily remained in remission while they received tofacitinib 5mg twice daily.29

Efficacy of tofacitinib for endoscopic lesions“Endoscopic improvement” was a secondary endpoint in the OCTAVE Induction 1 and 2 induction studies. It was defined as a Mayo endoscopic sub-score of 0–1. Table 3 sums up the most significant findings for the efficacy of tofacitinib with regard to endoscopic lesions. It should be noted that improvement of mucosal lesions was confirmed in 46% of patients after a year of treatment22; this is quite a high figure in comparison to other drugs such as biologic drugs.

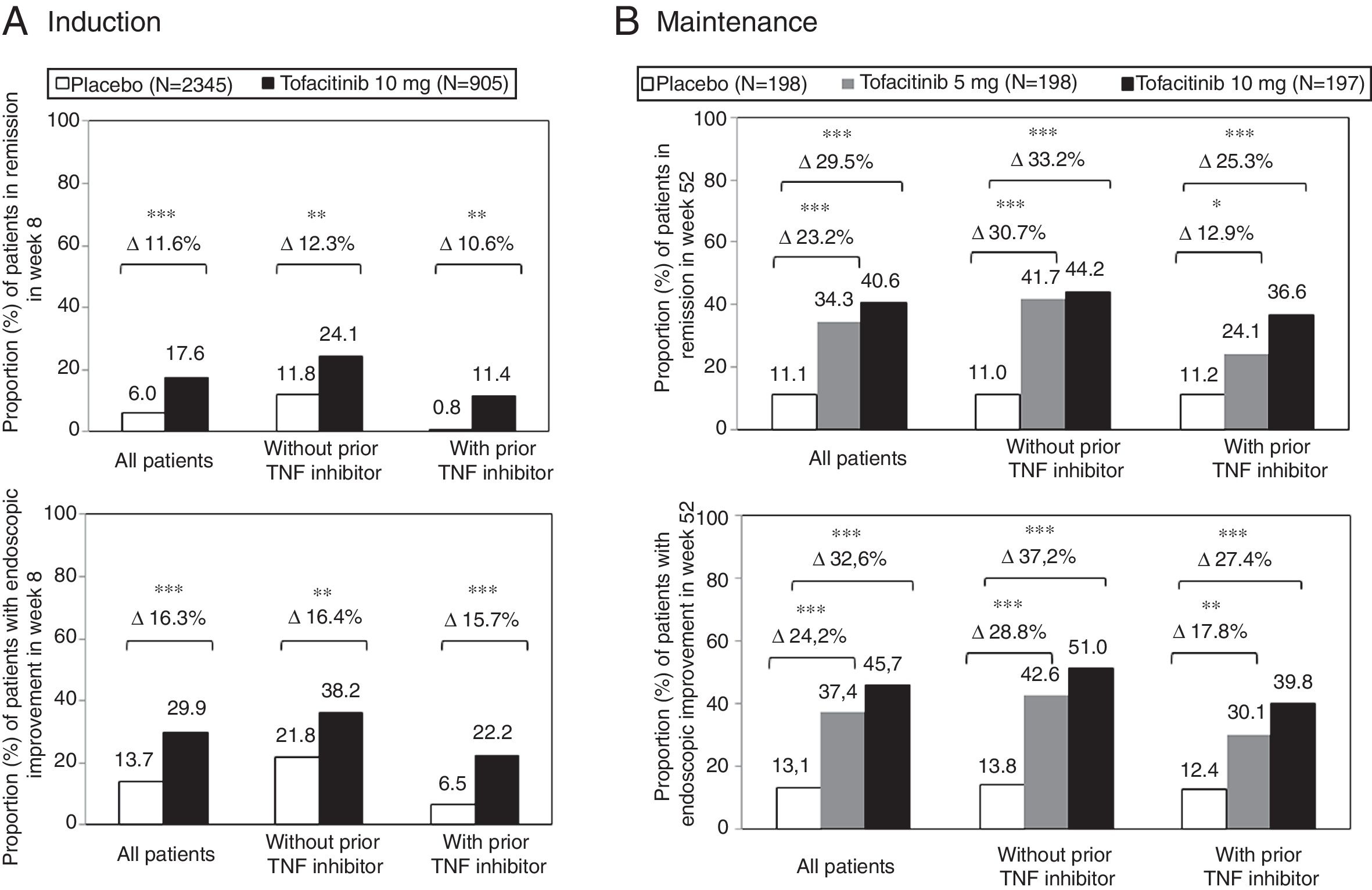

Efficacy of tofacitinib according to prior treatmentThe efficacy of tofacitinib was also analysed in pre-established sub-populations of patients: those with and without prior treatment with TNF inhibitor drugs and those treated and not treated with corticosteroids at the start of the study.22 In clinical studies of induction with tofacitinib, 52% of patients had previously experienced treatment failure with a TNF inhibitor drug. Among them, 56% had experienced primary failure, 39% had experienced secondary failure and 33% had experienced treatment failure with two or more TNF inhibitor drugs.30

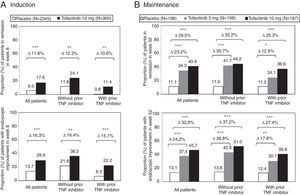

The therapeutic benefit of tofacitinib in induction of remission compared to placebo was similar in patients with and without prior treatment failure with TNF inhibitor drugs (Fig. 3A). In both sub-groups of patients, a higher proportion of patients treated with tofacitinib 10mg twice daily achieved clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in week 8 compared to the placebo group.11

Proportion of patients with and without prior TNF inhibitor drug treatment who (A) achieved clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in week 8 of the OCTAVE Induction 1 and 2 studies combined and (B) maintained clinical remission and endoscopic improvement in week 52 of the OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study.

Clinical remission: total Mayo score ≤2, with no sub-score >1 and a sub-score for rectal bleeding of 0. Endoscopic improvement: Mayo endoscopic sub-score 0–1. *p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.0001 vs placebo.

During maintenance treatment, the effects of treatment with tofacitinib 5 and 10mg twice daily were evident in patients with and without prior failure with TNF inhibitor drugs. The difference between treatment and placebo was similar for tofacitinib 5mg twice daily and tofacitinib 10mg twice daily in the sub-group of patients without prior failure of TNF inhibitor drugs. There were indeed differences between tofacitinib 5 and 10mg twice daily in patients who had experienced treatment failure with TNF inhibitor drugs before treatment with tofacitinib (Fig. 3B). Therefore, in some patients, such as those having previously experienced treatment failure with an TNF inhibitor drug, continuation of a dose of 10mg twice daily should be considered as maintenance treatment.11,30

Effect of tofacitinib on quality of lifeIn clinical studies of tofacitinib in patients with UC, better outcomes in terms of HRQoL (assessed using the IBDQ) have been seen in those treated with the drug than in those who received placebo.31–33

In the phase-2 clinical study, patients showed a preference for the study drug compared to other treatment options. In addition, treatment with tofacitinib was associated with a statistically significant dose-dependent improvement in HRQoL. Patients in whom endoscopic remission was achieved had a higher score on the IBDQ questionnaire.31 In a multivariate analysis that evaluated the associated factors that contributed the most to satisfaction with treatment, “bowel function” (bowel symptoms and frequency of bowel movements) was the most important for the satisfaction of the patient treated with tofacitinib.32

In the induction studies, treatment with 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily significantly improved HRQoL at four weeks. In the patients who showed a clinical response in the induction phase, the improvement achieved in HRQoL (compared to placebo) during that phase was maintained to a significant degree during the 52 weeks of maintenance treatment, on regimens of 5 and 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily.33

Finally, a systematic review and meta-analysis also found that tofacitinib is effective in short-term remission induction and improves patient quality of life.34

Strategies for optimisation of treatment with tofacitinibExtension of the induction period by 8 additional weeks (for a total of 16 weeks)Patients who did not achieve clinical response in the induction trials at 8 weeks received treatment with 10mg of tofacitinib, twice daily, for 8 more weeks. An additional 53% of these patients were seen to achieve clinical response and 14% achieved remission at the end of this period.22

Therefore, in patients in whom an adequate response was not achieved after 8 weeks with 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily, induction treatment may be prolonged by 8 weeks, for a total of 16 weeks, if their clinical condition allows it. If after 16 weeks of treatment with tofacitinib there are no signs of therapeutic benefit, treatment should be suspended.11

Dose escalation of tofacitinibAnother sub-analysis of the OCTAVE Open extension study included data for patients who, following achievement of clinical response at 8 weeks with 10mg of tofacitinib twice daily, received 5mg twice daily in the OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study and lost the clinical response achieved. These patients’ dose was escalated to 10mg twice daily (n=58), and clinical response and remission were recovered in 59% and 34% of cases, respectively, 8 weeks after dose escalation; these percentages rose to 69% and 52%, respectively, at 12 months.35 Therefore, patients on maintenance treatment with 5mg of tofacitinib, twice daily, with loss of response may benefit from a dose escalation to 10mg twice daily.35

Retreatment with tofacitinibFinally, patients who experienced loss of response after suspending active treatment or receiving placebo during the OCTAVE Sustain maintenance study restarted tofacitinib at a dose of 10mg twice daily. Clinical response was seen in 75% of patients, endoscopic improvement was seen in 55%, and 40% achieved clinical remission at 8 weeks of retreatment.36 Therefore, if loss of response follows suspension of treatment with tofacitinib, another induction with this drug at a dose of 10mg twice daily may be considered.11

Efficacy of tofacitinib and of biologic drugs in meta-analysesThe efficacy and safety of tofacitinib and biologic drugs in the treatment of UC have been summarised in various traditional and network meta-analyses.34,37 No direct comparisons have been made between tofacitinib and biologic drugs. Indirect analyses have not found any significant differences between the two treatment modalities, although a recent network meta-analysis did find that tofacitinib may be the most effective drug in maintenance of remission and endoscopic improvement.38 Other meta-analyses have concluded that tofacitinib is superior to biologic drugs in patients with prior treatment failure with TNF inhibitor drugs.39

Advantages of tofacitinib in the treatment of ulcerative colitisThe aim of treatment of UC is to achieve remission, since persistent clinical activity, even mild, reduces quality of life.40 The remission rates achieved with current biologic drugs (TNF inhibitor and vedolizumab) or with new drugs in their final stages of development are 20–35%, with response rates around 60–70%. Put simply, none of these treatments achieves clinical remission for most patients.40 Therefore, new treatment strategies with different mechanisms of action are needed.41

An obvious advantage of small-molecule drugs versus biologic drugs is their administration by the oral route (versus the parenteral route, either intravenous or subcutaneous). Notably, the use of tofacitinib versus intravenous drugs would allow the costs associated with administration by the intravenous route (scheduling of visits for intravenous administration, specialised staff, consumables, special conditions for storage, etc.) to be brought down.42

With biologic drugs, it may be necessary to optimise the dose based on plasma levels of the active substance. With tofacitinib, this is not necessary as this drug has linear pharmacokinetics, meaning that the relationship between the dose administered and the serum levels achieved is linear and therefore predictable.40,43 In addition, the half-life of small-molecule drugs is quite a bit shorter, resulting in rapid drug clearance in situations that might call for it, such as a serious infection or pregnancy.44

A significant advantage of tofacitinib is that it does not cause immunogenicity, unlike biologic drugs, especially TNF inhibitor drugs. Therefore, loss of response due to development of immunogenicity may be predicted to be null.45,46

Finally, the costs of production of tofacitinib are lower than those of biologic drugs. The latter are produced by means of genetic engineering, with possible changes in the production process that may bring about changes in efficacy and immunogenicity. By contrast, small-molecule drugs are produced by means of chemical synthesis,42 which means that there is no variability in their composition.

Consideration of the safety aspects of tofacitinib is not one of the objectives of this review. By way of a summary, tofacitinib's safety profile is similar to that of the immunosuppressants and biologic drugs used for the treatment of UC, apart from the fact that the incidence of herpes zoster is slightly higher with tofacitinib.22,47 However, many cases were classified as mild or moderate, affecting a single dermatome, and resolved in most instances without stopping medication.22,47

ConclusionThe efficacy of tofacitinib has been shown in patients with moderate to severe UC, in both induction and maintenance treatment. Its route of administration is oral, it is used in monotherapy, it has a rapid effect on the disease and it does not cause immunogenicity. Therefore, tofacitinib represents an appealing treatment in patients with UC who experience treatment failure or intolerance to conventional treatment or a biologic drug.

Conflicts of interestDr Gisbert contributed as a speaker, consultant and advisory member, or has received research funding from: MSD, Abbvie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Roche, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Casen Fleet, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

Dr Panés contributed as a speaker, consultant and advisory member, or has received research funding from: Pfizer, Abbvie, Arena, Biogen, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Celgene, Genentech, Gilead, GoodGut, GSK, Janssen, MSD, Nestlé, Novartis, Oppilan, Progenity, Roche, Shire, Sigmoid Pharma, Takeda, Theravance, TiGenix and Topivert.

The authors would like to thank Mónica Valderrama, Ana Cábez and Susana Gómez of Pfizer for reviewing this manuscript, as well as Dr Ana Moreno Cerro and Anabel Herrero, PhD, for their assistance with preparing the draft on behalf of Springer Healthcare with funding from Pfizer España.

Please cite this article as: Panés J, Gisbert JP. Eficacia de tofacitinib en el tratamiento de la colitis ulcerosa. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:403–412.