Colorectal cancer screening programmes have been shown to reduce incidence and mortality. High-risk adenomas (HRA) are the most frequently diagnosed lesions in these programmes, and these patients are referred to a specialist. However, few studies have evaluated the adherence of HRA patients to the recommended endoscopic follow-up.

ObjectivesTo analyse follow-up adherence and duration in patients diagnosed with HRA in a screening programme.

MethodsRetrospective cohort study of patients diagnosed with HRA within one of the participating hospitals of the colorectal cancer screening programme of Barcelona, during the first round of the programme (2010–2011). The follow-up period was 75.5 months. Descriptive analyses, logistic regression and survival models were performed.

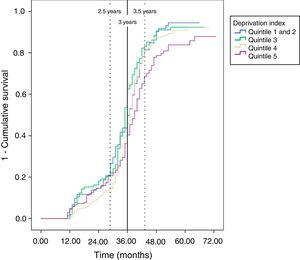

Results602 patients were included in the study, 66.6% of which were men. The adherence rate was 83.7% (n=504). Follow-up colonoscopy was performed within the recommended time (36±6months) in 57.7%, with a mean follow-up of 34 months. The Cox regression only showed differences at the socioeconomic level, with a lower adherence rate in the most deprived quintile (HR 0.70; 95% CI, 0.53–0.93).

ConclusionsCompared to previous studies, the follow-up adherence rate is considered to be acceptable. However, follow-up was not performed within the recommended time frame in a high proportion of cases. There is a need to further explore the reasons leading to lower follow-up adherence in the most deprived socioeconomic group and to increase the equity of the programme beyond participation.

Los programas de detección precoz de cáncer colorrectal han demostrado reducir la mortalidad y la incidencia de este cáncer. Del conjunto de lesiones diagnosticadas en los programas, los adenomas de alto riesgo (AAR) son las más frecuentes. Los AAR son derivados al especialista pero son escasos los estudios que han evaluado la adherencia al seguimiento endoscópico recomendado.

ObjetivosAnalizar la adherencia y el intervalo de seguimiento de personas diagnosticadas de AAR en un programa de cribado.

MétodosEstudio de cohorte retrospectivo, de personas diagnosticadas de AAR en uno de los centros hospitalarios del Programa de detección precoz de cáncer colorrectal en Barcelona durante la primera ronda (2010–2011). El periodo de observación fue de 75,5 meses. Se realizaron análisis descriptivos y modelos de regresión logística y de supervivencia.

ResultadosLa población de estudio fue de 602 personas, el 66,6% hombres. La tasa de adherencia fue del 83,7% (n=504). El 57,7% realizaron la colonoscopia de seguimiento en el intervalo de tiempo recomendado (36 ±6meses), con una media de 34 meses. En la regresión de Cox solo se observaron diferencias según el índice socioeconómico, con menor adherencia en el quintil de mayor privación (HR 0,70; IC 95%: 0,53–0,93).

ConclusionesLa adherencia al seguimiento se consideró aceptable al compararla con estudios previos, si bien en un alto porcentaje no se realizó en el tiempo recomendado. Es necesario explorar los motivos de la menor adherencia del grupo de mayor privación para diseñar estrategias que mejoren la equidad del Programa más allá de la participación.

In Catalonia, colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cause of cancer death for both genders, with an incidence rate of 47.9 cases in men and 28.2 cases in women per 100,000 inhabitants,1 which is similar to the figures reported for Spain.2 The risk of developing CRC is higher among men and increases with age (90% of cases are diagnosed in individuals over the age of 50).3,4 Screening programmes have been shown to reduce CRC incidence and mortality.3

In 2006, the Spanish National Healthcare System approved the use of population-based screening programmes based on biennial faecal occult blood tests (FOBT) in men and women aged 50–69 years.5 Catalonia was the first autonomous community to implement a CRC screening pilot programme in the year 2000.6 The first round (2010–2011) of the Barcelona colorectal cancer screening programme (PDPCCR-BCN), aimed initially at residents of two of the four integral healthcare areas, started in December 2009.

The screening test used is the immunological FOBT; when the test is positive (≥20μg/g faeces), a colonoscopy is recommended for diagnosis purposes. The most common findings are polyps, most of which are adenomas, which are classified as low-, moderate- and high-risk adenomas in terms of the risk of progression to cancer based on their size, number and histology. This classification determines the recommended endoscopic follow-up intervals.

High-risk adenomas ([HRA] 5 or more small adenomas or at least one adenoma ≥20mm)3 represent the most common group, with a detection rate during the first round (2010–2011) of 21.7% (41.5% of all colonoscopies performed during the Programme).7 Lesion follow-up recommendations in effect at the start of the Programme were those outlined in the AEG-SEMFyC Clinical Practice Guideline (2009 update, Barcelona), which recommended performing a follow-up colonoscopy on those patients with HRA 3 years after the baseline colonoscopy.4 These individuals were excluded from the Screening programme and referred to either the reference primary care centre or specialised CRC units for follow-up, based on the typology of the lesion.8 As a follow-up to the PDPCCR-BCN, letters were sent out to these individuals within the 6 months prior to the end of the recommended 3-year period to remind them to make an appointment for a follow-up colonoscopy. Since the third round (2014–2015), lesions have been classified and recommendations have been made based on European guidelines for colorectal cancer screening and diagnosis.3

Very few studies have evaluated adherence to follow-up in this group of patients within the context of screening programmes as most are designed within a clinical context and show a wide variation in endoscopic adherence. In a recent study conducted in Spain,9 within the framework of a clinical trial, 65.5% adherence to follow-up colonoscopy was observed in HRA patients diagnosed through a screening programme, with a mean time to colonoscopy of 2.8±1years. In the Netherlands, Van Heijningen et al.10 observed endoscopic follow-up in 66.0% of individuals diagnosed with adenoma (low- and high-risk), while Jonkers et al.11 described 85.3% adherence to follow-up in patients with colorectal adenomas, with time to follow-up longer than the recommended time in 32.5% of cases and shorter than the recommended time in 27.3% of cases (both in clinical practice). In the United States, Braschi et al.12 showed that 21.4% completed follow-up at 3 years after diagnosis of HRA; Greenspan et al.13 observed 89.3% adherence for all adenomatous polyps, with patients receiving phone calls 3 and 7 days prior to their appointment (both in a clinical context). In opportunistic CRC screening in Germany,14 adherence of less than 50.0% was observed in patients with colorectal adenomas (35.6% in patients with HRA), and only 28.0% completed follow-up within the recommended interval of 36 months.

The aim of this study is to analyse adherence to follow-up colonoscopy in patients diagnosed with HRA during the first round (2010–2011) of the PDPCCR-BCN, and to analyse the interval between screening colonoscopy and follow-up colonoscopy and its relationship to socio-demographic variables (gender, age and deprivation index).

Material and methodsA retrospective cohort study was conducted. The study population included individuals diagnosed with HRA after participating in the first round (2010–2011) of the PDPCCR-BCN. It included those individuals who were residents of the hospital's area of influence and whose medical records and files were available to the investigators (which embarks half of the territory covered at that time by the PDPCCR-BCN). Individuals who had undergone endoscopic follow-up within the first year of their screening colonoscopy (as this was considered part of the baseline process, for example, in cases of fragmented resection), those requiring special follow-up and deaths within the first year (from the time of the baseline colonoscopy) were excluded. The study period ran from 1st January 2010 to 15th April 2016.

The study population and information on the study variables (gender, age, date of screening colonoscopy and basic healthcare area) for the individuals were obtained from the PDPCCR-BCN database. The deprivation index variable used was the MEDEA index,15 created initially to analyse socio-economic inequalities in mortality. The index was calculated for each census tract using 5 indicators from the 2001 census (percentage of manual labourers, unemployment, casual workers, inadequate education and inadequate education for young people). This type of measure may be useful when the effect of socio-economic characteristics in a determined context on small geographical areas needs to be analysed, or when socio-economic deprivation may be a confounding factor which needs to be controlled. Furthermore, use of this census-based deprivation index represents a homogeneous source for the whole of Spain, allowing comparisons between different regions. This index was divided into quintiles for this study and, due to the limited number of individuals in quintile 1 (least deprived), this quintile was merged with quintile 2.

Information on patient follow-up was obtained from the hospital's colonoscopy database and a database held by the Gastrointestinal Department, and was then completed by manually reviewing each medical record. Other variables were also created: adherence to follow-up (showing whether a follow-up colonoscopy was performed during the study period or not) and duration of follow-up (time between the date of the screening colonoscopy and the follow-up colonoscopy).

Univariate and bivariate analyses were performed on all variables along with logistic regression and survival models to analyse adherence to follow-up and time to follow-up colonoscopy (Kaplan–Meier and Cox regression models). All regression models were adjusted for gender, age and deprivation index. A sensitivity analysis for data missing from the deprivation index was performed. IBM-SPSS version 21 statistics software was used. All analyses were performed in accordance with current legislation and current European Union and national conventions and declarations on ethical standards in research projects. The protocol for this study was approved by the Independent Ethics Committee prior to conducting this study.

ResultsA total of 1734 individuals were diagnosed with HRA in round one of the PDPCCR-BCN and 650 (37.5%) of these belonged to the study area. A total of 48 patients (7.4%) were excluded: 46 due to undergoing endoscopic follow-up in the last year and/or requiring special follow-up, and 2 as a result of death during the first year. The final study population was 602 patients with a mean age of 59.7 years and 66.6% men.

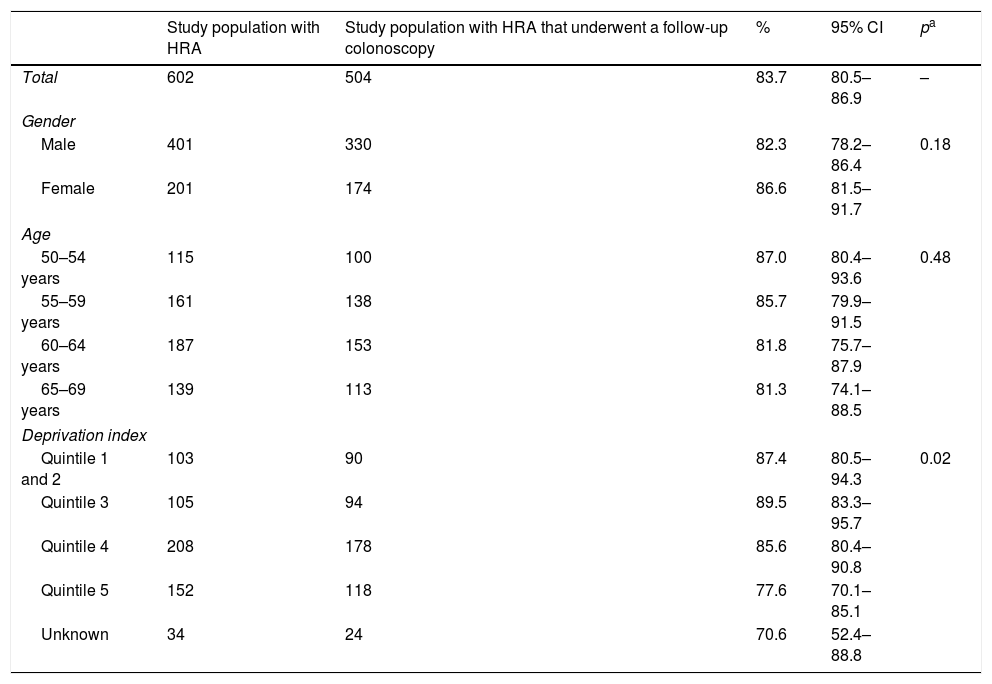

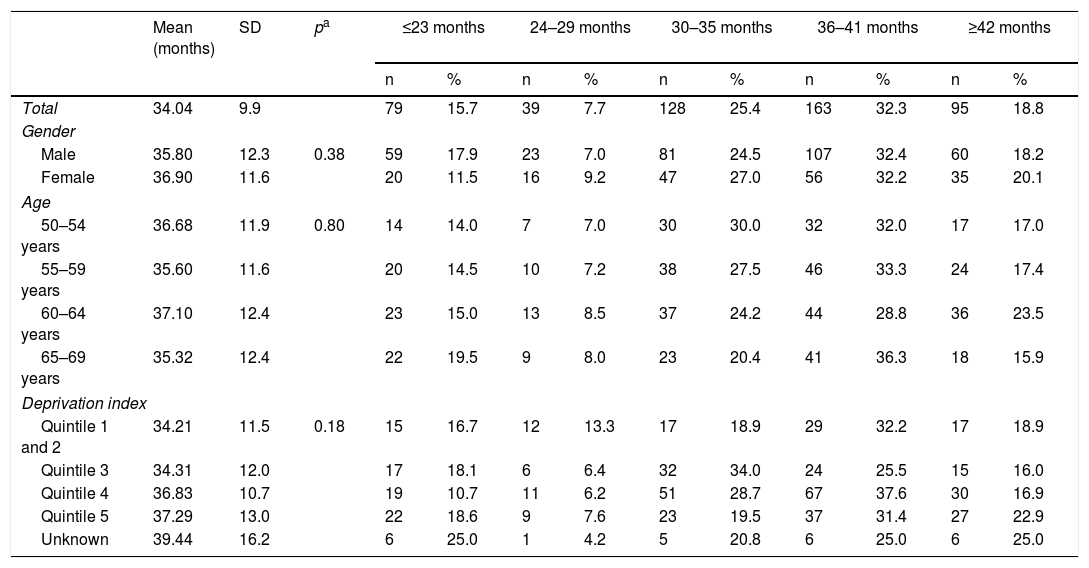

In total, 504 patients underwent a follow-up colonoscopy within the study period, which gives an overall rate of adherence of 83.7%. No significant differences based on gender or age were found, but there were significant differences based on deprivation index as adherence was lower in the most deprived quintile compared to the least deprived quintile (77.6% versus 87.4%, respectively) (Table 1). The mean time between the baseline colonoscopy and the follow-up colonoscopy was 34 months (SD±9.9), with no significant differences based on gender, age or deprivation index. More than half of the patients (57.7%) who underwent an endoscopic follow-up did so within a time frame of 2.5–3.5 years; 23.4% underwent follow-up within less than 2.5 years and 18.8% underwent follow-up after 3.5 years (Table 2).

Population that participated in round 1 of the PDPCCR-BCN with a screening colonoscopy and a follow-up colonoscopy, according to gender, age and deprivation index.

| Study population with HRA | Study population with HRA that underwent a follow-up colonoscopy | % | 95% CI | pa | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 602 | 504 | 83.7 | 80.5–86.9 | – |

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 401 | 330 | 82.3 | 78.2–86.4 | 0.18 |

| Female | 201 | 174 | 86.6 | 81.5–91.7 | |

| Age | |||||

| 50–54 years | 115 | 100 | 87.0 | 80.4–93.6 | 0.48 |

| 55–59 years | 161 | 138 | 85.7 | 79.9–91.5 | |

| 60–64 years | 187 | 153 | 81.8 | 75.7–87.9 | |

| 65–69 years | 139 | 113 | 81.3 | 74.1–88.5 | |

| Deprivation index | |||||

| Quintile 1 and 2 | 103 | 90 | 87.4 | 80.5–94.3 | 0.02 |

| Quintile 3 | 105 | 94 | 89.5 | 83.3–95.7 | |

| Quintile 4 | 208 | 178 | 85.6 | 80.4–90.8 | |

| Quintile 5 | 152 | 118 | 77.6 | 70.1–85.1 | |

| Unknown | 34 | 24 | 70.6 | 52.4–88.8 | |

HRA: high-risk adenoma; CI: confidence interval; PDPCCR-BCN: Barcelona colorectal cancer screening programme.

Time interval between baseline and follow-up colonoscopy in those patients with high-risk adenoma, according to gender, age and deprivation index.

| Mean (months) | SD | pa | ≤23 months | 24–29 months | 30–35 months | 36–41 months | ≥42 months | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | ||||

| Total | 34.04 | 9.9 | 79 | 15.7 | 39 | 7.7 | 128 | 25.4 | 163 | 32.3 | 95 | 18.8 | |

| Gender | |||||||||||||

| Male | 35.80 | 12.3 | 0.38 | 59 | 17.9 | 23 | 7.0 | 81 | 24.5 | 107 | 32.4 | 60 | 18.2 |

| Female | 36.90 | 11.6 | 20 | 11.5 | 16 | 9.2 | 47 | 27.0 | 56 | 32.2 | 35 | 20.1 | |

| Age | |||||||||||||

| 50–54 years | 36.68 | 11.9 | 0.80 | 14 | 14.0 | 7 | 7.0 | 30 | 30.0 | 32 | 32.0 | 17 | 17.0 |

| 55–59 years | 35.60 | 11.6 | 20 | 14.5 | 10 | 7.2 | 38 | 27.5 | 46 | 33.3 | 24 | 17.4 | |

| 60–64 years | 37.10 | 12.4 | 23 | 15.0 | 13 | 8.5 | 37 | 24.2 | 44 | 28.8 | 36 | 23.5 | |

| 65–69 years | 35.32 | 12.4 | 22 | 19.5 | 9 | 8.0 | 23 | 20.4 | 41 | 36.3 | 18 | 15.9 | |

| Deprivation index | |||||||||||||

| Quintile 1 and 2 | 34.21 | 11.5 | 0.18 | 15 | 16.7 | 12 | 13.3 | 17 | 18.9 | 29 | 32.2 | 17 | 18.9 |

| Quintile 3 | 34.31 | 12.0 | 17 | 18.1 | 6 | 6.4 | 32 | 34.0 | 24 | 25.5 | 15 | 16.0 | |

| Quintile 4 | 36.83 | 10.7 | 19 | 10.7 | 11 | 6.2 | 51 | 28.7 | 67 | 37.6 | 30 | 16.9 | |

| Quintile 5 | 37.29 | 13.0 | 22 | 18.6 | 9 | 7.6 | 23 | 19.5 | 37 | 31.4 | 27 | 22.9 | |

| Unknown | 39.44 | 16.2 | 6 | 25.0 | 1 | 4.2 | 5 | 20.8 | 6 | 25.0 | 6 | 25.0 | |

SD: standard deviation

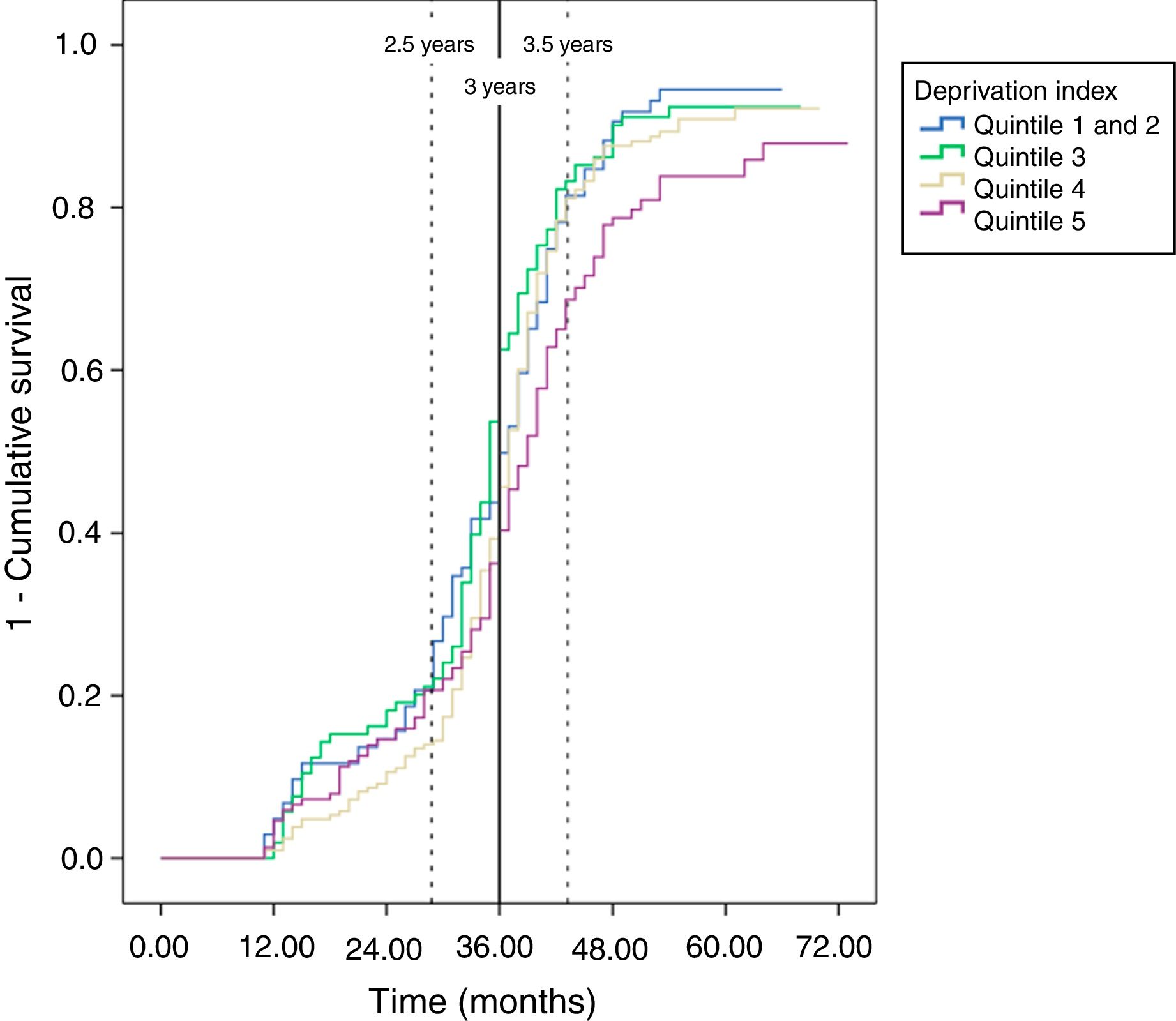

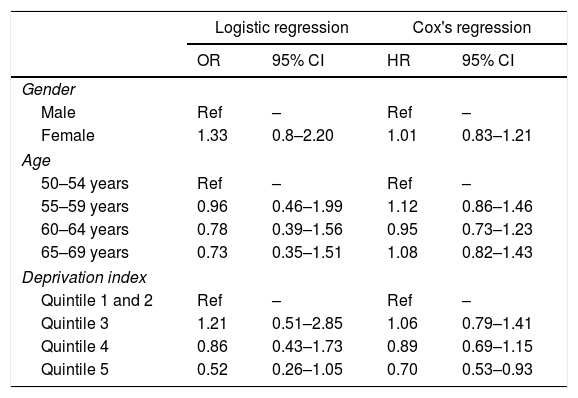

In the analysis (logistic regression) adjusted for gender, age and deprivation index, none of these variables had a statically significant impact on the probability of adherence to follow-up (Table 3). However, the descriptive analysis of the probability of undergoing a follow-up colonoscopy within the set time (Kaplan-Meyer curve) revealed that the most deprived group (quintile 5) showed less adherence to follow-up than the least deprived group (Fig. 1). These results were also observed when adjusted for duration of follow-up (Cox's regression), with the most deprived quintile showing a lower probability of adherence to follow-up colonoscopy than the least deprived group (quintile 1 and 2) (HR 0.70; 95% CI: 0.53–0.93) (Table 3).

Odds ratio (OR) for adherence to follow-up and hazard ratio (HR) for duration of follow-up, adjusted for gender, age and deprivation index (No.=568 patients, not including missing deprivation index values).

| Logistic regression | Cox's regression | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | HR | 95% CI | |

| Gender | ||||

| Male | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Female | 1.33 | 0.8–2.20 | 1.01 | 0.83–1.21 |

| Age | ||||

| 50–54 years | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| 55–59 years | 0.96 | 0.46–1.99 | 1.12 | 0.86–1.46 |

| 60–64 years | 0.78 | 0.39–1.56 | 0.95 | 0.73–1.23 |

| 65–69 years | 0.73 | 0.35–1.51 | 1.08 | 0.82–1.43 |

| Deprivation index | ||||

| Quintile 1 and 2 | Ref | – | Ref | – |

| Quintile 3 | 1.21 | 0.51–2.85 | 1.06 | 0.79–1.41 |

| Quintile 4 | 0.86 | 0.43–1.73 | 0.89 | 0.69–1.15 |

| Quintile 5 | 0.52 | 0.26–1.05 | 0.70 | 0.53–0.93 |

A follow-up colonoscopy was performed during the study period for 83.7% of the patients diagnosed with HRA during the first round (2010–2011) of the PDPCCR-BCN and belonging to the area of one of the city's hospitals. No significant differences were observed across gender and age. However, the most deprived group of patients showed significantly lower adherence to follow-up than the least deprived group. With regard to duration of follow-up, taking into account that guidelines in effect at that time recommended 3 years of follow-up, and accepting a margin of ±6months, more than half of the adherent patients (57.7%) underwent a colonoscopy within the recommended period, while 23.4% underwent a colonoscopy early and 18.8% were late.

The authors consider that the adherence to follow-up observed in this study is acceptable when compared with the results published in other studies. The only Spanish study contemplating adherence to colonoscopy discovered is a clinical trial that obtained 65.5% adherence.9 Observational studies conducted in a clinical context in the Netherlands10 and the United States12 obtained lower rates of adherence of 66 and 21.4%, respectively. Those studies in which patients already had an appointment for a colonoscopy and/or using telephone or postcard reminders obtained higher rates of adherence: 85.3% in the Netherlands11 and 89.3% in the US.13 As far as the authors are aware, this is the first study conducted in the screening context to evaluate adherence to follow-up based on socio-economic factors; therefore, this study cannot be compared with earlier results.

This study obtained a mean follow-up of 2.8±0.8years, which is very similar to the results obtained by Cubiella et al. in Spain.9 57.7% of the colonoscopies performed took place within the time frame recommended by guidelines in effect at that time (3years±6months). Other authors11,14,16–19 who have obtained similar time intervals concluded that these are not adequate and that greater adherence is required. In our context, it must be noted that 23.4% underwent follow-up earlier than the recommended period of 3 years, which may be a reflection of the ongoing change towards current recommendations (endoscopic follow-up one year after diagnosis of HRA),20 and only 18.8% underwent follow-up later than the recommended interval.

This study has some limitations. Firstly, only those individuals diagnosed with HRA at one of the two hospital sites involved in the Programme were included, which may limit the external validity of the study. Taking into consideration the fact that patients diagnosed with HRA at the other site have a less deprived profile (data not shown), and that there appears to be an inverse correlation between deprivation and adherence, overall adherence is expected to be higher.

Secondly, information on follow-up colonoscopies performed outside the study site was not available as this information was not included in their medical histories. Nevertheless, given the relatively high rate of adherence to follow-up obtained, and taking into account the high attraction rate of the hospital studied21 and the fact that individuals have already participated in the Programme, the number of colonoscopies performed outside the study site is expected to be small. Another possible limitation is due to the deprivation index used, which is an ecological deprivation index,15 based on census tract and not individual data. Nevertheless, it has been shown in various studies that ecological deprivation indices are fairly accurate measures of an individual's actual deprivation, including in colorectal cancer screening.22–24

It is also important to highlight the quality of the PDPCCR-BCN database as an accurate source of data with structured, reviewed information. The study also had access to databases containing information on endoscopic follow-up, which provided reliable data on colonoscopies performed on individuals with HRA. Use of the MEDEA index15 allowed analysis according to socio-economic status, a variable which very few studies have access to, especially in Spain.

The diagnosis of high-risk patients by screening programmes requires a large volume of follow-up colonoscopies that must be covered by the healthcare system over successive years. In one recent study conducted in Barcelona25 using a simulation model, it was estimated that the total number of colonoscopies generated by the Screening programme would double over the next 20 years, due primarily to the increase in follow-up colonoscopies. This study provides important data for calculating estimated requirements for endoscopic resources generated as a result of a population-based screening programme since knowing the actual adherence to endoscopic follow-up will improve the accuracy of such estimates.

Moreover, the use of reminder systems, whether by phone13,26,27 or by postcard,27 for clinical endoscopic procedures has been shown to have an impact on adherence to such procedures. Greenspan et al.13 obtained a rate of adherence of 89.3% after making two phone calls prior to colonoscopy appointments in the United States; and in another clinical trial27 also conducted in the US, adherence improved to 44.7% (with reminder) versus 22.6% (without reminder). In another study based on clinical practice and conducted by Adams et al.26 in Australia, non-adherence rates declined significantly from 12.2% to 9.0% after implementing reminder systems. Since the PDPCCR-BCN, reminder letters have been sent out routinely approximately 2.5 years after the baseline colonoscopy to those patients diagnosed with HRA, reminding them to see their doctor to schedule a colonoscopy. Although it has not been possible to evaluate the impact of these letters, it is reasonable to assume that they had a positive effect on adherence.

This study only analyses adherence to follow-up by those individuals with HRA. With regard to extrapolating these results to follow-up for other diagnoses, less favourable results in terms of adherence to follow-up should be expected for those diagnoses with longer recommended endoscopic follow-up intervals during the first round of the Programme, as is the case with low-risk adenomas (recommendation of 5 years). Since the third round (2014–2015), individuals diagnosed with this type of lesion remain in the Programme and are invited back for a FOBT 2 years after diagnosis.

Finally, and in view of the results obtained in this and other studies, the paradox that the medium-risk population (included in population-based screening programmes) may be better controlled than the higher-risk population, whose follow-up and control depends on clinical structures and partly on the patients themselves, may arise. In this sense, it may be necessary to assess the need to include follow-up colonoscopies for those high-risk patients diagnosed from screening within the structure and management of population-based programmes, instead of excluding them as is currently the case in Spain.

To summarise, adherence to endoscopic follow-up after diagnosis of HRA by a screening programme in an urban context is around 84%. The lower rate of adherence detected in more deprived patients emphasises the need to investigate the reasons for such difference and to take into consideration the characteristics of the population for follow-up invitation and reminder strategies. Likewise, implementation of systems to improve adherence, such as reminder letters, email alerts, etc., is recommended. Such systems should be coordinated by the screening programmes, primary care and specialised care, and the effectiveness and efficiency of such measures should be evaluated in terms of adherence and the resources used. It would also be a good idea to study follow-up by individuals excluded from the Programme after diagnosis of other diseases.

FundingThis study is not part of any funded project and has not received any additional funding.

Conflict of interestThe authors declare that there is no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this article.

We would like to thank: Albert Prats, Julieta L. Politi, Oleguer Parés and Borja Casañ for their help and methodological and statistical support during this study; and Cristina Hernández for her help with data extraction.

Procolon is the research group of the Barcelona colorectal cancer screening programme (www.prevenciocolonbcn.org) and is currently comprised of the following members: Rafael Abós, Eva Abril, Marta Aldea, Cristina Álvarez, Marco Antonio Álvarez, Montserrat Andreu, Isis Araujo, Josep M. Augé, Anna Aymar, Guillermo Bagaria, Francesc Balaguer, Mercè Barau, Xavier Bessa, Montserrat Bonilla, Andrea Burón, Sabela Carballal, Antoni Castells, Xavier Castells, Mercè Comas, Rosa Costa, Míriam Cuatrecasas, Josep M. Dedeu, Mireya Diaz, Maria Estrada, Imma Garrell, Jaume Grau, Rafael Guayta, Cristina Hernández, Mar Iglesias, María López-Cerón, Laura Llovet, Francesc Macià, Leticia Moreira, Lorena Moreno, M. Francisca Murciano, Gemma Navarro, Jordi Gordillo, Teresa Ocaña, Maria Pellisé, Mercè Pintanell, Àngels Pozo, Faust Riu, Liseth Rivero-Sánchez, Cristina Rodríguez, Maria Sala, Ariadna Sánchez, Agustín Seoane, Anna Serradesanferm, Judit Sivilla, Antoni Trilla, Isabel Torà.

Please cite this article as: Otero I, Burón A, Macià F, Álvarez-Urturi C, Comas M, Román M, et al. Adherencia al seguimiento de las personas con adenoma de alto riesgo diagnosticadas y excluidas del Programa de detección precoz de cáncer de colon y recto de Barcelona. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;41:226–233.