We present the case of a young woman who developed a rare complication secondary to an intragastric balloon, requiring its removal. This has only been previously described once in the literature.1

The prevalence of overweight is increasing worldwide. At the same time, the intragastric balloon is becoming established as an effective, safe and well-tolerated treatment in patients with morbid obesity, especially in cases in which dietary, pharmacological and behavioural modification therapies have failed, or as a step prior to bariatric surgery.2,3 This, together with the fact that weight loss is maintained in almost half of patients 1 year after removing the balloon,2,3 has led to an increase in the use of this technique.

A 20-year-old woman with a history of an eating disorder (bulimia nervosa) and implantation of an intragastric balloon 5 months previously came to the emergency department for severe epigastric pain radiating to the left hypochondrium that had commenced the previous day, associated with nausea and vomiting. She denied dietary transgression and alcohol or drug ingestion. On examination, her abdomen was soft and non-tender, with no signs of peritonism. Blood tests revealed: amylase 875U/L (normal: 28–100), lipase 187U/L (normal: 16–36), C-reactive protein 28.78mg/dL (normal: 0–0.5), and leukocytes 18,170/mm3 (normal: 4800–10800) with neutrophilia. The rest of the biochemistry tests (including triglycerides and calcium), full blood count and coagulation were normal.

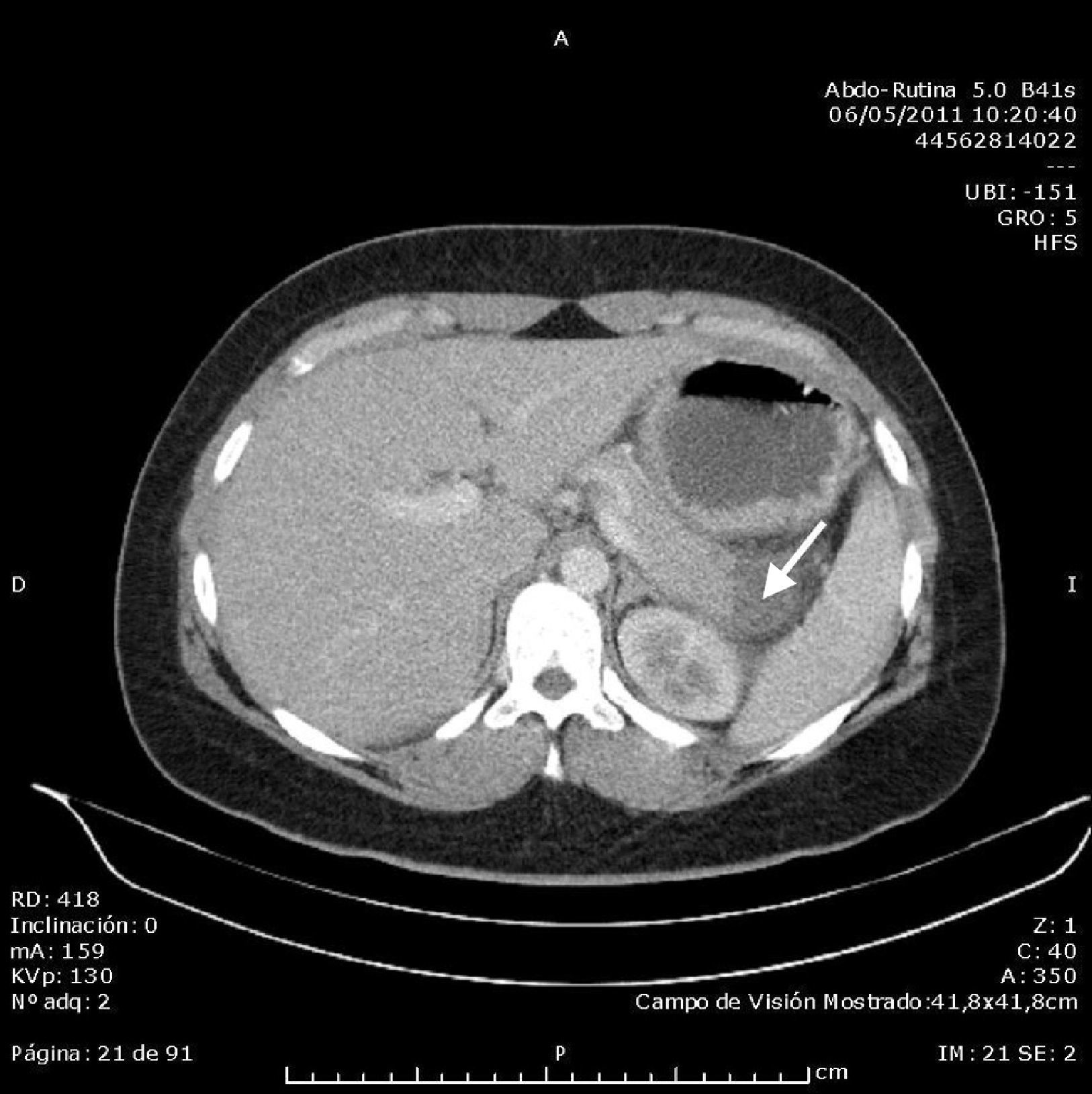

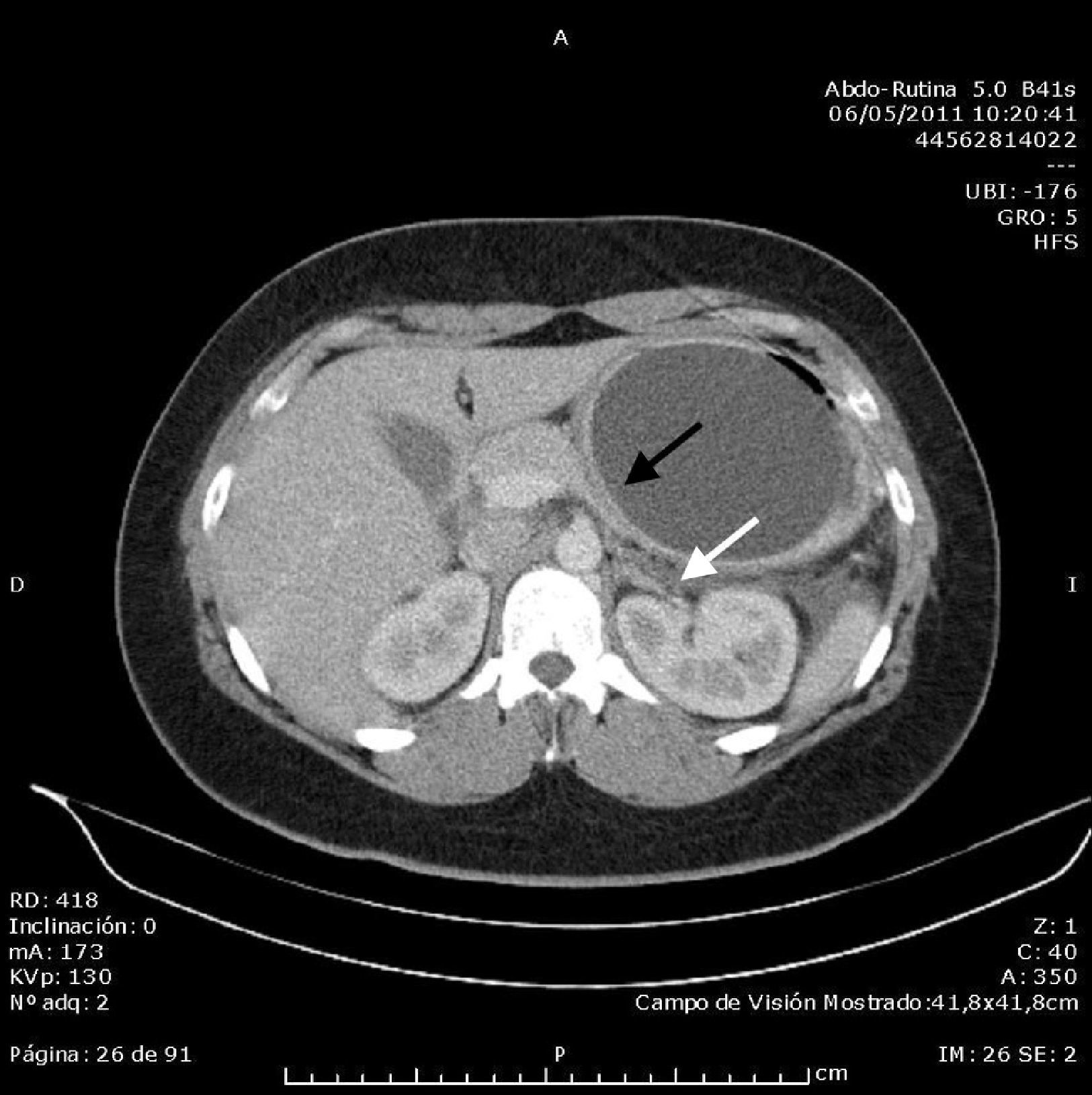

Abdominal ultrasound found an acalculous gallbladder and head and body of the pancreas with no abnormalities, although the tail could not be visualised due to the presence of the intragastric balloon, which measured around 10cm. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the abdomen and pelvis without contrast showed an area with decreased uptake in the tail of the pancreas measuring around 23×24mm, with rarefaction of the adjacent fat, consistent with focal pancreatitis of the tail (Balthazar stage C) with less than 30% pancreatic necrosis; the intragastric balloon and minimal free fluid in the pouch of Douglas were also visualised (Figs. 1 and 2). Once other causes of acute pancreatitis, such as congenital malformations, trauma or tumour, had been ruled out by the CT images, the diagnosis of acute pancreatitis secondary to compression of the tail of the pancreas by intragastric balloon was established by exclusion. The patient progressed well with symptomatic treatment, with the abdominal pain receding and laboratory parameters returning to normal levels. On discharge, it was recommended that the balloon be removed in the centre where it had been implanted.

Acute pancreatitis is a common inflammatory process, with an incidence in the United States of around 40 cases per 100,000 persons.4 Global mortality in hospitalised patients with acute pancreatitis is approximately 10% (range: 2–22%), reaching 30% in the subset with necrotising acute pancreatitis.5

Acute pancreatitis is caused by gallstones and excessive alcohol consumption in 75–85% of cases. Hypertriglyceridaemia is the most common metabolic cause, accounting for 1–4% of cases,5,6 followed by hypercalcaemia (in hyperparathyroidism, acute pancreatitis presents in less than 1.5% of all cases).4 Other causes are5,6: drugs (antibiotics such as tetracyclines, furosemide, oestrogens, immunosuppressants, neuropsychiatric agents), tumours, annular pancreas/pancreas divisum, Oddi sphincter dysfunction, trauma, invasive procedures (endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, surgery), infections and genetic causes (PRSS1, SPINK1, CFTR).

After reviewing the literature, we found only 1 case similar to the one presented here.1 In both, the aetiology of the acute pancreatitis was attributed to the presence of an intragastric balloon, despite correct positioning. In our patient, it occurred after 5 months, close to the date scheduled for balloon removal (at 6 months).

The intragastric balloon is a temporary alternative to reduce weight in moderately obese persons. It is not available for use in the United States outside of clinical trials, as it has still not been approved by the Food and Drink Administration.7 It consists of a silicone balloon with capacity for 400 to 650mL of physiological saline and methylene blue. It is placed endoscopically and, due to the space that it occupies in the stomach, promotes a feeling of early satiety after eating and reduces the appetite. The balloon should be extracted by endoscopy using the specific material provided by the marketing company. This should be done within 6 months, as this is the extent of the manufacturer's guarantee, and because after this time, the efficacy of the balloon decreases considerably.3,7

The intragastric balloon is indicated8,9: (a) in obese patients with comorbidities refractory to conservative treatment, (b) in severe obesity, as a step prior to bariatric surgery, and (c) to reduce surgical risk in obese patients who will require a non-bariatric intervention. Side effects include nausea and vomiting (in up to 70–90% of patients), halitosis, abdominal pain, constipation, oesophagitis, ulcer, balloon migration, and other more severe effects such as gastric perforation and even death.9,10

This case highlights an unusual complication to consider in patients with an intragastric balloon, and requires removal of the device.

Please cite this article as: Selfa Muñoz A, Calzado Baeza SF, Palomeque Jiménez A, Casado Caballero FJ. Pancreatitis aguda asociada a balón intragástrico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2016;39:603–604.