Liver haemangiomas are the most common primary tumours of the liver with a prevalence of 5–20%. Believed to be of congenital aetiology and benign, they consist of intrahepatic vascular malformations characterised by cavernous spaces lined with flat endothelial cells. They are most prevalent in middle-aged women, tend to be diagnosed as an incidental finding and generally manifest as single lesions measuring less than 4cm. Large haemangiomas are known as giant or cavernous. They tend to be asymptomatic, irrespective of their size. Phenomena of intratumoral bleeding have been reported very sporadically, as well as Kasabach-Merritt syndrome and systemic inflammatory response syndrome secondary to haemangioma in very exceptional cases.1,2

In this article, we present a case of systemic inflammatory response syndrome secondary to a giant haemangioma.

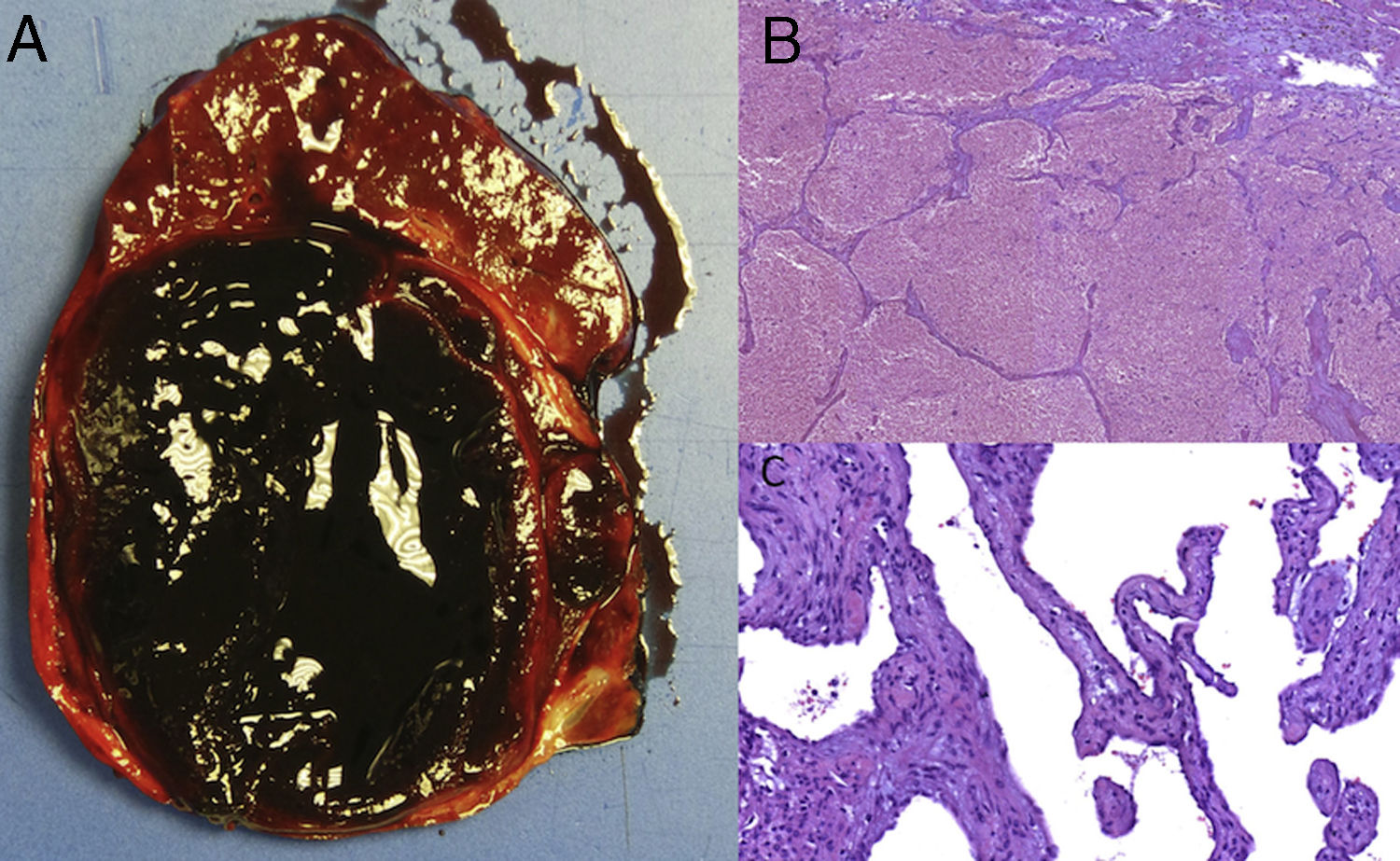

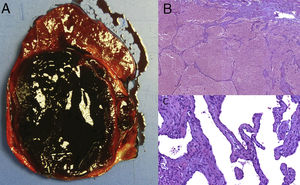

The case concerns a 49-year-old female patient with a 10-cm liver haemangioma in the right liver lobe (RLL) discovered in 2013 following a computed tomography (CT) scan performed for another reason and asymptomatic to date. In January 2018, the patient experienced discomfort in her right upper quadrant and daily fever of up to 39°C without signs of infection or constitutional symptoms. An abdominal CT scan was performed at another centre, which revealed growth of the haemangioma to 14cm, with some intratumoral bleeding, associated with anaemia. In light of these findings, the patient underwent percutaneous embolisation of the right hepatic and phrenic arteries. Despite empirical antibiotic therapy with meropenem and teicoplanin, fever persisted after one month, so the patient was referred to our centre for diagnostic and therapeutic assessment. The blood test revealed elevated inflammatory markers with persistently high C-reactive protein levels of around 25mg/dl (reference range: <1mg/dl), without leukocytosis, and an abnormal liver profile of anicteric cholestasis (GGT 260U/l, AP 175U/l), with AST 39U/l, ALT 43U/l and bilirubin 0.4mg/dl. All blood and urine cultures were negative. The study was concluded with an MRI that showed the 14-cm liver haemangioma in the RLL compressing the bile duct, right portal branch and suprahepatic vein, without collapsing them. No abscesses, sites of bleeding, lymphadenopathies or other abnormalities were observed in the structures of the abdominal or lower thoracic cavities. Having ruled out other processes that could explain the persistent fever, a suspected diagnosis of systemic inflammatory response syndrome secondary to giant liver haemangioma was established. Treatment was started with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, without achieving clinical response. After deliberation by the multidisciplinary committee, the haemangioma was resected by right hepatectomy extended to segments IVa and IVb. The patient experienced no post-operative complications, inflammatory marker levels quickly fell and the fever abated. Analysis of the surgical specimen confirmed that it was a largely necrotic cavernous haemangioma with a peak diameter of 15cm, with no sites of abscess formation or cholangitis and with free resection margins (Fig. 1).

Surgical specimen of right hepatectomy: (A) macroscopic image. Well-defined tumour of friable haemorrhagic appearance with a peak diameter measuring 14cm. (B) Microscopic image showing vascular canals containing blood, with extensive changes caused by coagulative necrosis (H&E, ×4). (C) Microscopic image at higher magnification showing vascular spaces lined with flat endothelial cells without atypia (H&E, ×20).

Following a literature review, very few cases (<20) of systemic inflammation associated with giant haemangioma were found. All exhibited high fever and sweating with elevated inflammatory markers and no leukocytosis, although without haemodynamic repercussions or impaired liver function, with negative screening for infectious disease, and haemangioma being the only finding. Although the exact pathophysiology of the syndrome is not fully understood, it has been suggested that it may be associated with the release of inflammatory mediators like interleukin-1 and interleukin-6 by the macrophages and endothelial cells of the haemangioma in response to intratumoral necrosis.3,4 With regards to treatment, the administration of corticosteroids and anti-inflammatories has been reported with variable response rates. However, most cases ultimately required tumour excision by segmental resection or hepatectomy to definitively resolve the symptoms.5

In summary, although most giant liver haemangiomas are asymptomatic and do not require any form of treatment, in exceptional cases they can cause significant complications like systemic inflammatory response syndrome. In such cases, surgical resection is considered the treatment of choice as it achieves complete abatement of symptoms and resolution of lab test abnormalities.2

Please cite this article as: Caballol B, Ruiz P, Ferrer-Fàbrega J, Diaz A, Forner A. Una causa infrecuente de síndrome inflamatorio sistémico. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:383–384.