Ultrasound has an excellent diagnostic performance when Crohn’s disease is suspected, when performing an activity assessment, or determining the extension and location of Crohn's disease, very similar to other examinations such as MRI or CT. It has a good correlation with endoscopic lesions and allows the detection of complications such as strictures, fistulas or abscesses. It complements colonoscopy in the diagnosis and, given its tolerance, cost and immediacy, it can be considered as a good tool for disease monitoring. In ulcerative colitis, its role is less relevant, being limited to assessing the extent and activity when it is not possible with other diagnostic techniques or if there are doubts with these. Despite its advantages, its use in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is not widespread in Spain. For this reason, this document reviews the advantages and disadvantages of the technique to promote knowledge about it and implementation of it in IBD Units.

La ecografía tiene un excelente rendimiento diagnóstico tanto cuando se sospecha una enfermedad de Crohn como en la valoración de la actividad o en determinar su extensión y localización, muy similar a otras exploraciones como resonancia magnética o tomografía computarizada. Tiene una buena correlación con las lesiones endoscópicas y permite la detección de complicaciones como estenosis, fístulas o abscesos. Complementa a la colonoscopia en el diagnóstico y dada su tolerancia, coste e inmediatez, es una buena herramienta para la monitorización de la enfermedad. En la colitis ulcerosa su papel es menos relevante, limitándose a valorar la extensión y actividad cuando no sea posible o haya dudas con otras técnicas diagnósticas. A pesar de sus ventajas, su empleo en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal (EII) no está muy extendido en nuestro país, por este motivo el presente documento revisa las virtudes e inconvenientes de la técnica para favorecer su conocimiento e implantación en las Unidades de EII.

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic condition with exacerbations which, over time, can cause complications that lead to varying degrees of disability. Colonoscopy is the recommended technique for both the initial diagnosis and the follow-up of IBD.1 However, colonoscopy can only assess the mucosa and endoluminal findings. The assessment is also limited to the colon and terminal ileum. In Crohn's disease (CD) specifically, with its transmural nature and involvement of other bowel segments, this means that the study may be incomplete. Consequently, the main consensus documents recommend performing an imaging test that complements colonoscopy,1 preferably one which does not involve radiation. Options are limited to magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and abdominal ultrasound. Although MRI is common practice in most of Europe, the same cannot be said of ultrasound, the use of which varies greatly from country to country.2 In view of the low level of implementation of abdominal ultrasound here in Spain, at the GETECCU (Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa [Spanish Working Group on Crohn's Disease and Ulcerative Colitis]) we have decided to review the advantages and disadvantages of the technique, the main findings and how to correctly interpret them, and the positioning of the technique in the management of IBD.

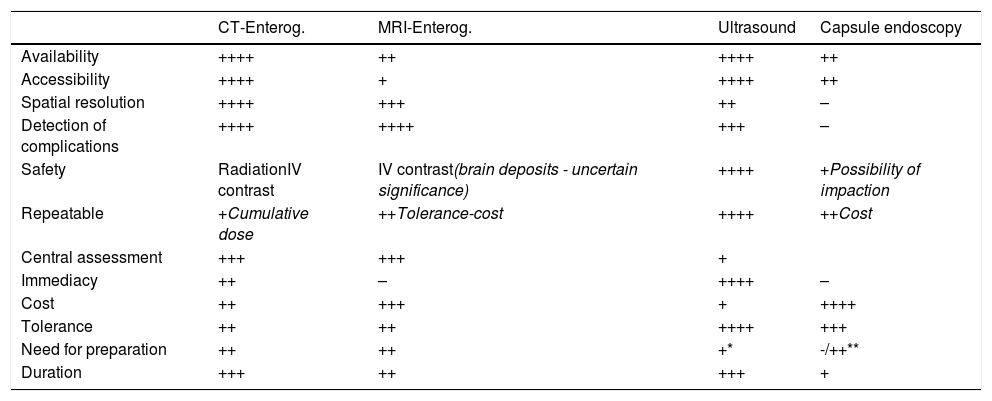

Advantages of intestinal ultrasoundIntestinal ultrasound has significant advantages in the diagnosis and assessment of IBD (Table 1). It is very well tolerated by the patient, can be performed without specific preparation and is very accessible, cheap and non-invasive.

Differences between the main imaging techniques in CD.

| CT-Enterog. | MRI-Enterog. | Ultrasound | Capsule endoscopy | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Availability | ++++ | ++ | ++++ | ++ |

| Accessibility | ++++ | + | ++++ | ++ |

| Spatial resolution | ++++ | +++ | ++ | – |

| Detection of complications | ++++ | ++++ | +++ | – |

| Safety | RadiationIV contrast | IV contrast(brain deposits - uncertain significance) | ++++ | +Possibility of impaction |

| Repeatable | +Cumulative dose | ++Tolerance-cost | ++++ | ++Cost |

| Central assessment | +++ | +++ | + | |

| Immediacy | ++ | – | ++++ | – |

| Cost | ++ | +++ | + | ++++ |

| Tolerance | ++ | ++ | ++++ | +++ |

| Need for preparation | ++ | ++ | +* | -/++** |

| Duration | +++ | ++ | +++ | + |

The excellent tolerance facilitates the use of ultrasound in IBD monitoring, enabling treatment to be adjusted based on the ultrasound assessment, and this has been associated with improvement in patients' clinical outcomes.3 In studies comparing the tolerance of the different diagnostic techniques in IBD, intestinal ultrasound comes first, at the same level as a blood test, and with a perceived utility similar to MRI.4

Another great advantage is its immediacy, as it can be performed without any prior preparation. This is known as point of care ultrasonography (POCUS), and it has been proven to speed up quality decision-making, both in initial diagnosis and in monitoring.5,6

The technique is also less expensive than MRI. A published decision model shows the most cost-effective strategy in the diagnosis of CD to be colonoscopy in conjunction with intestinal ultrasound.7 Another great advantage of the technique is its innocuous nature when compared to ileocolonoscopy (invasive) or computed tomography (CT) scan (radiation).8

Overall, the sensitivity and specificity figures for intestinal ultrasound are similar to those of CT and MRI in the diagnosis of CD and in assessing the severity of the disease.9,10 It performs less well in the assessment of some segments (rectum and retroperitoneal duodenum) and specific findings (abscesses or fistulas) located in the deep pelvis or retroperitoneum.10–13

Ultrasound performance is operator-dependent and the equipment used and the build of the patient are also influencing factors.10,14 However, assessing the interobserver variability of intestinal ultrasound, Fraquelli et al.15 found a good degree of agreement in the measurement of intestinal wall thickness, colour Doppler evaluation, presence of lymphadenopathy, free fluid and the detection of strictures, all important parameters in the diagnosis of the disease and in assessing the inflammatory activity.

Technique, equipment, physical principlesConventional and high-frequency (at least 5 MHz) transducers are required to be able to distinguish between the layers of the intestinal wall.

The examination includes a B-mode ultrasound study, following a systematic examination of the abdomen, using the gradual compression technique and focusing on locations where the patient shows pain or tenderness.16,17 A Doppler study should also be performed, optimised for the detection of slow flows from the small vessels of the intestinal wall (low wall filter, high gain and low velocity scale).11,14,15,18

The scan can be performed without preparation, although fasting of at least four hours is recommended for planned ultrasounds to avoid ingestion-related peristalsis causing interference with the Doppler. In certain circumstances, the examination can be completed with oral intake of a variable volume (250−800 ml) of an isotonic contrast solution (polyethylene glycol) to distend the loops.11,16 Studies using this technique, known as SICUS (small intestine contrast ultrasonography), show a greater capacity to assess the proximal small intestine, detect strictures and evaluate postoperative recurrence, as well as reducing interobserver variability.19,20 However, the duration of the procedure increases from 25 to 45−60 min and complicates the assessment in colour Doppler mode.21,22

Intravenous (IV) contrast increases the sensitivity in detecting the vascularisation of the intestinal wall, compared to the study in colour Doppler mode. A sulphur hexafluoride microbubble ultrasound contrast agent (SonoVue®) is used, which is eliminated via the respiratory tract and has an excellent safety profile. To assess hyperaemia with intravenous contrast, specific software is used in which time-intensity curves are obtained which make it possible to quantify the enhancement of the intestinal wall.23,24 There is wide variability in the measurements obtained with IV contrast from one piece of equipment to another, so it is recommended, as far as possible, to use the same ultrasound machine and transducer for monitoring the disease.

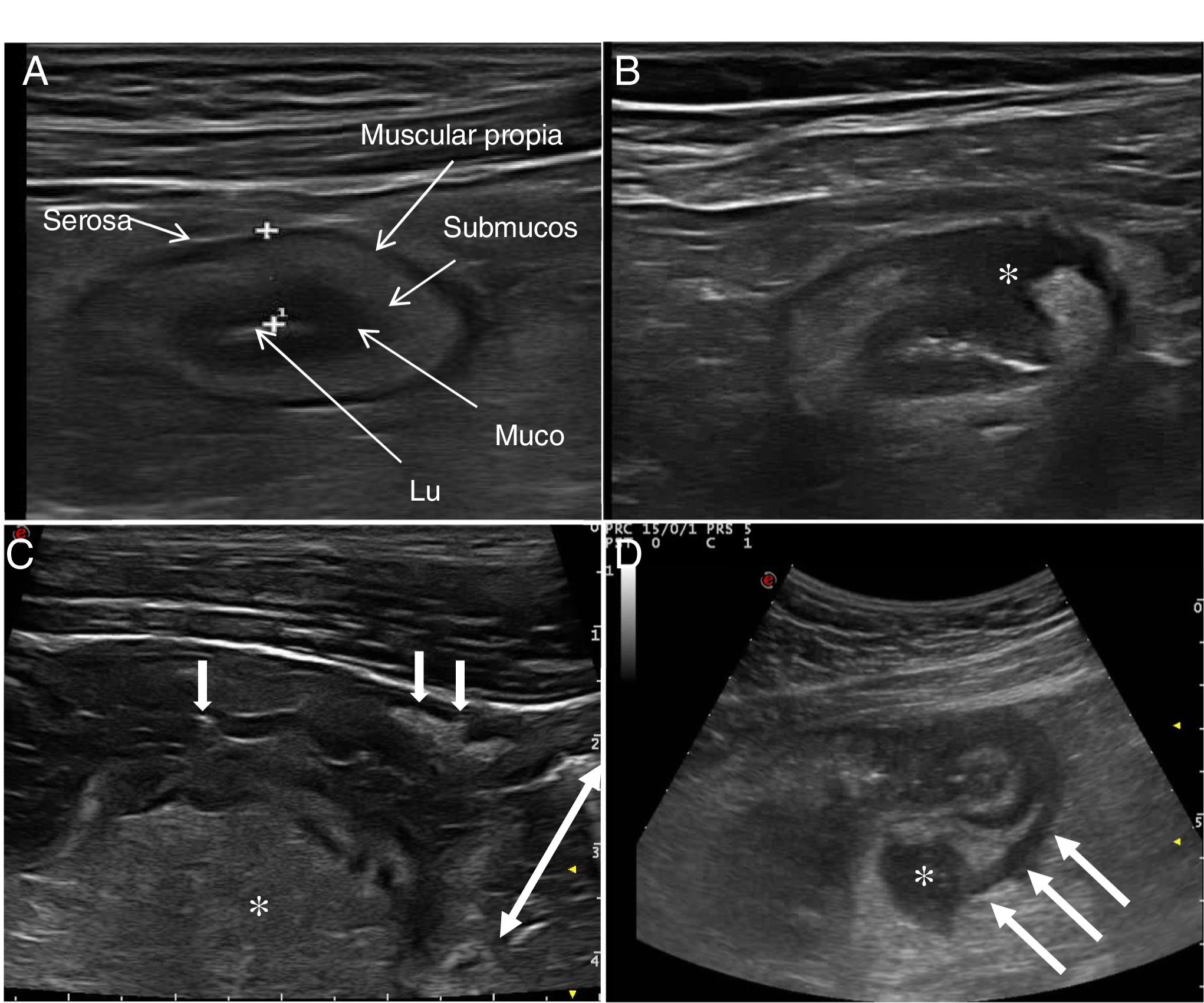

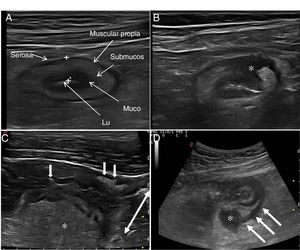

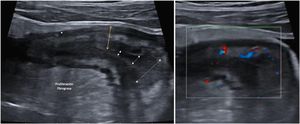

Ultrasound in Crohn's diseaseMain findings of USA typical ultrasound feature of CD is thickening of the intestinal wall, which affects the terminal ileum in up to 70% of cases and which may be characteristically discontinuous. Other typical findings are predominance of the submucosal layer, deep ulcers, disruption of the layer structure, creeping fat, stricture, fistulas, phlegmons and abscesses (images 1–3).

Ultrasound parameters of activityWall thickeningWall thickness is the most robust ultrasound parameter for diagnosis and assessment of disease activity (Fig. 1) and has low interobserver variability.15,25

The normal thickness of the bowel wall is less than 2 mm.26 The cut-off point with the highest sensitivity and specificity to consider an intestinal loop as pathological was between 4 mm (sensitivity 89% and specificity 96%)27 and 3 mm (sensitivity 89.7% and specificity 95.6%) in the two recently published meta-analyses. The European Federation of Societies for Ultrasound in Medicine and Biology (EFSUMB) consensus document recommends using a cut-off point of 3 mm to obtain greater sensitivity in the diagnosis and assessment of activity.28

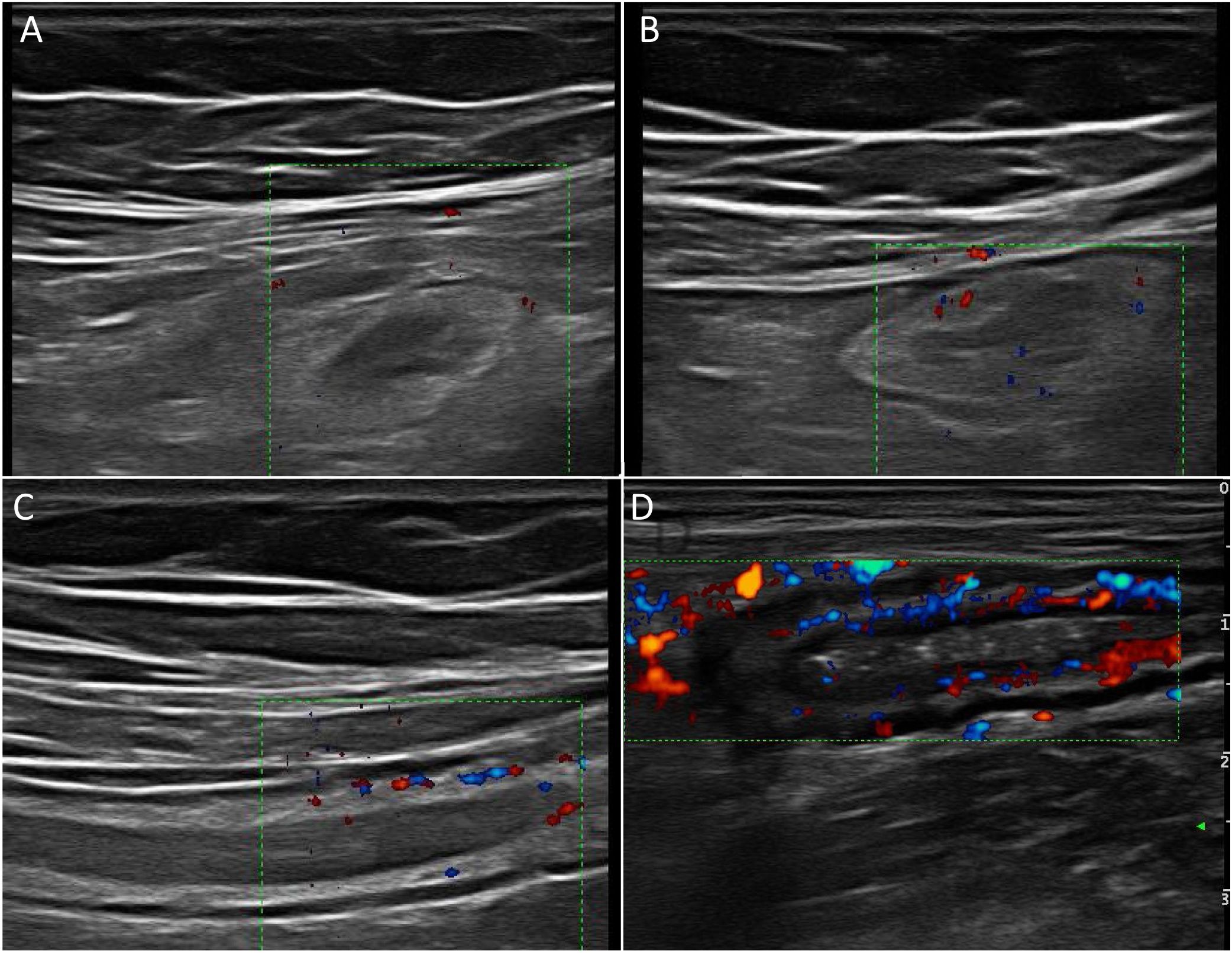

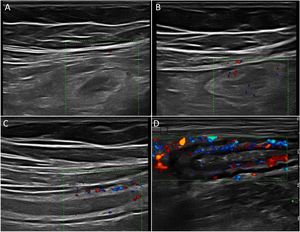

Wall hyperaemiaAnother diagnostic standard for detecting activity is wall hyperaemia detected with colour Doppler ultrasound (Fig. 2). Vessel density is assessed using the modified Limberg semi-quantitative score, which classifies the degree of wall vascularity from 0 to 3.29 This scale has shown a good correlation with the histological findings,12,30,31 endoscopic activity31–34 and the clinical activity31,35–39 of the disease. The persistence of wall hyperaemia could be associated with increased risk of a flare-up of the disease.39

Ultrasound with IV contrast increases the diagnostic sensitivity (87-97%) in the detection of hyperaemia compared to colour Doppler, although with less specificity (60.5-87%).32,34,40,41

Echotexture of the wallHigh-frequency probes show intestinal wall echotexture with higher resolution than MRI.42 The layer pattern may be preserved or there may be focal or segmental loss of structure (Fig. 1). Focal wall loss has been associated with the presence of deep longitudinal ulcers (with a sensitivity of 91% and a specificity of 100%43) and with an increased risk of requiring surgery.43–45

Ultrasound can also identify the presence of ulcers (Fig. 3), which are recognised as hyperechoic images that penetrate the wall to varying degrees. In some series,42 the diagnostic capacity of ultrasound is superior to MRI for the detection of ulcers, with a diagnostic accuracy of 80.7% compared to 58.5% with MRI.

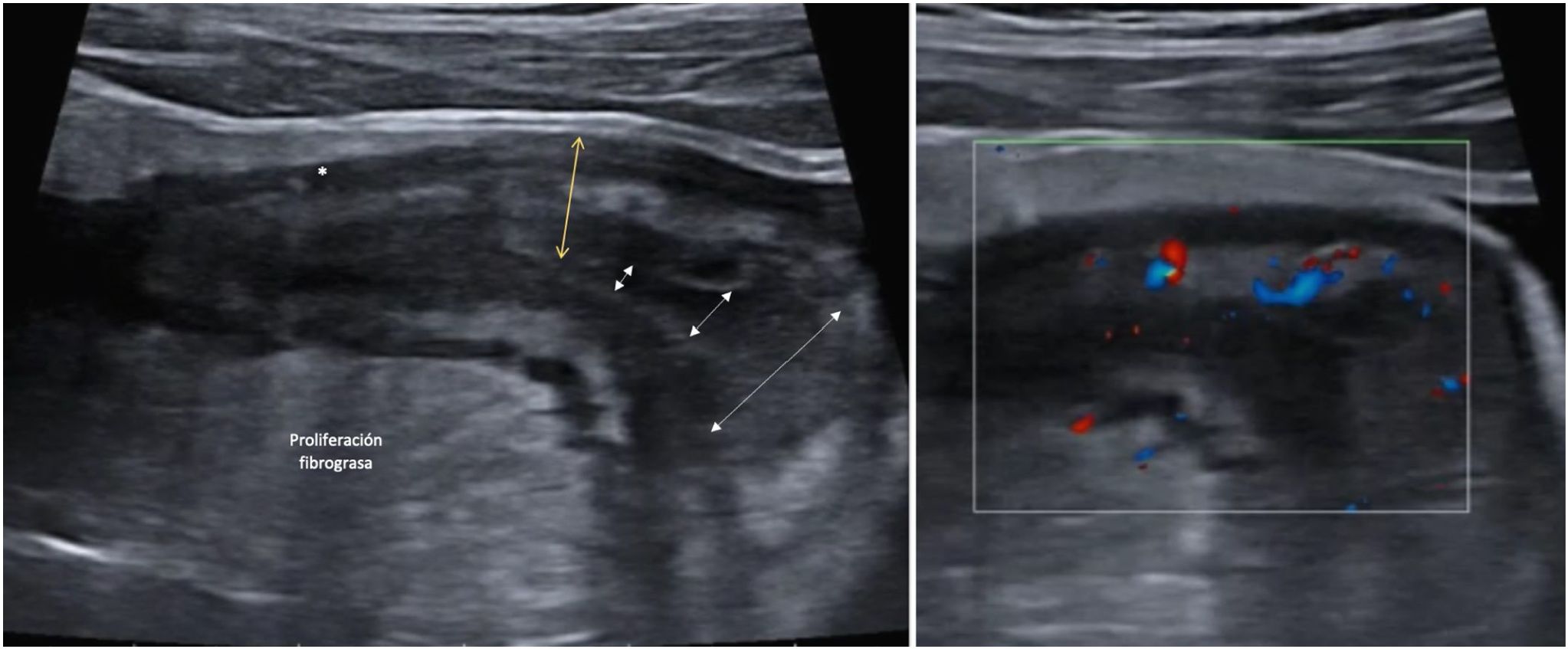

Creeping fatAnother ultrasound parameter commonly associated with active CD is mesenteric fat involvement. It is characterised by a homogeneous increase in echogenicity surrounding an affected bowel segment. This finding is identified in up to 47% of patients and is significantly associated with the presence of fistulas (OR = 13.5) and pathological wall thickening (OR = 7.6).46 However, it can also persist in up to 24% of patients with quiescent CD without being associated with an increased risk of recurrence (Fig. 4).

A: Stricture of the lumen (dashed arrows indicate progressive narrowing of the lumen). It is accompanied by very evident creeping fat and an ulcer (asterisk). B: Marked Doppler signal (Limberg 2-3) indicating the presence of hyperaemia and it is therefore a stricture with inflammatory activity.

Lymph nodes are identified in approximately 25% of patients with CD.47,48 They are more common and occur in higher numbers in childhood, at the onset of the disease, as well as in patients with fistulas and abscesses. Enlarged lymph nodes may disappear after starting treatment.47

Extension and locationThe European Crohn's and Colitis Organisation and European Society of Gastrointestinal and Abdominal Radiology (ECCO-ESGAR) guidelines support the use of intestinal ultrasound, MRI and capsule endoscopy (CE) for the study of disease extension and location.49

Intestinal ultrasound has a comparable diagnostic accuracy to MRI and CE in locating the disease.12,50 Its sensitivity and specificity for the location of affected segments are 86-94% and 94-96% respectively,10,12 showing excellent performance in ileocaecal disease, but with worse results than CE for disease location in proximal segments (jejunum or proximal ileum),51–53 and worse than MRI in the deep location of the pelvis or rectum.10,13,54–56 The accuracy of intestinal ultrasound also depends on the severity of the disease, with endoscopy being more sensitive than imaging techniques for the detection of mild forms (in terminal ileum and colon).10,49 When assessing the length of the affected segment, MRI has better concordance with the surgical findings, while ultrasound underestimates the extension, especially when the segment is over 20 cm long.12

ComplicationsStricturesA stricture (Fig. 3) can be defined as a thickened (>4 mm), stiff bowel segment with narrowing of the lumen and distension of the proximal bowel segment.12 With oral contrast, it is defined when the diameter of the lumen of the affected segment is less than 1 cm, measured at the point of maximum distension of the loop.57

Ultrasound, CT and MRI all have high sensitivity and specificity for the diagnosis of small intestine and colon strictures, with similar diagnostic accuracy.10,49,58 In the case of ultrasound, the sensitivity for detecting strictures is 79.7% and the specificity, 94.7%.13 The sensitivity increases to 92% if we use oral contrast.13

There is no single diagnostic test at present capable of determining the fibrotic or inflammatory component of strictures.59 In fact, histologically most strictures are mixed.60 By ultrasound, the destructuring of the layer pattern is associated with a greater inflammatory component while the hyperechogenicity of the submucosal layer is associated with a greater fibrotic component,13,61 although these results have not been contrasted in larger series. The degree of hyperaemia with colour Doppler30,62 or enhancement with contrast62–65 have been shown to have a good correlation with the degree of fibrosis or inflammation, with the most useful parameters being the maximum peak, the percentage of enhancement and the time to peak.57 Lastly, one of the advances with ultrasound which could be promising in terms of characterisation of strictures is elastography. This technique makes it possible to assess the stiffness of the tissue using specific software included in the ultrasound equipment. In a recent systematic review,66 higher mean quantitative elastography values were found in fibrotic strictures, although the authors point to high heterogeneity between studies and a high risk of bias.

FistulasFistulas derive from transmural fissures and sinus tracts, which initially appear as hypoechoic irregularities on the external margin of the wall.67–69 As inflammation progresses, hypoechoic pathways form in the mesenteric fat which can come to a blind end or end in a mesenteric inflammatory mass.70,71 The fistulas connect epithelialised structures to each other or to the skin. They can occur between loops of the small intestine (enteroenteric), with the colon (enterocolic), bladder (enterovesical) or vagina (enterovaginal).12,61,68,69,72 The presence of gas within the fistulas will show up as echogenic foci that reverberate within the hypoechoic tract.

The sensitivity of ultrasound for the diagnosis of fistulas is similar to that described for CT and MRI and varies from 67 to 87%, with a specificity of 90-100%.10,13,73 The latest ECCO-ESGAR consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and monitoring of IBD recommend intestinal ultrasound as one of the imaging techniques to evaluate fistulising complications.49

Transperineal (or even transvaginal) ultrasound is helpful in perianal fistulas and abscesses. In a recent systematic review, the sensitivity in the detection of abscesses reached 86% with a positive predictive value (PPV) of 90%. Accuracy in fistula detection is even higher (sensitivity 98%, PPV 95%).74 We do not comment on endoanal ultrasound here because it is beyond the scope of these recommendations.

Phlegmons and abscessesAbscesses usually form as a result of fistulas or complications from surgery.67 They show up on ultrasound as hypo- or anechoic masses, with posterior reinforcement and well-defined thick walls, and may contain gas. Phlegmons are seen as hypoechoic inflammatory masses with poorly defined margins and no identifiable wall.12,61,67,69,71,72,75

Abscesses and phlegmons can occasionally have a similar appearance on B-mode ultrasound, and differentiation between the two is important for deciding on management. Colour Doppler ultrasound can help make the differentiation, by showing vascularisation inside the phlegmon, while in the abscess vessels are only seen in the wall. The use of ultrasound contrast has made it easier to safely distinguish between the two, with phlegmons showing diffuse enhancement of the lesion while in abscesses the enhancement is peripheral, with an internal avascular portion due to fluid content.76 The contrast better defines the size of the abscess.

The sensitivity of ultrasound for the diagnosis of abdominal abscesses ranges from 81 to 100%, with a specificity of 92-94%, similar to CT and MRI. They are more difficult to assess in certain anatomical areas such as the deep pelvis or retroperitoneum, due to the presence of gas, which can hide the lesions or be mistaken for an intestinal loop.13,57,73

Ultrasound is particularly useful as a guide in draining collections and in monitoring the lesion if the patient is treated with antibiotics and anti-TNF.77 Therefore, ultrasound with IV contrast should be considered the diagnostic technique of choice for differentiating between phlegmon and abscess, and in monitoring response to therapy.13

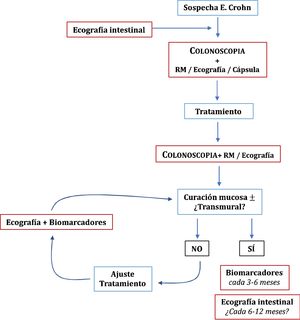

Overall positioning in the management of Crohn's diseaseInitial diagnosisAlthough an ileocolonoscopy is recommended for the initial diagnosis of CD, it should always be complemented with an examination that investigates the small intestine, whether CE, MRI or ultrasound,49 as this changes management in 50-60% of the patients.78,79

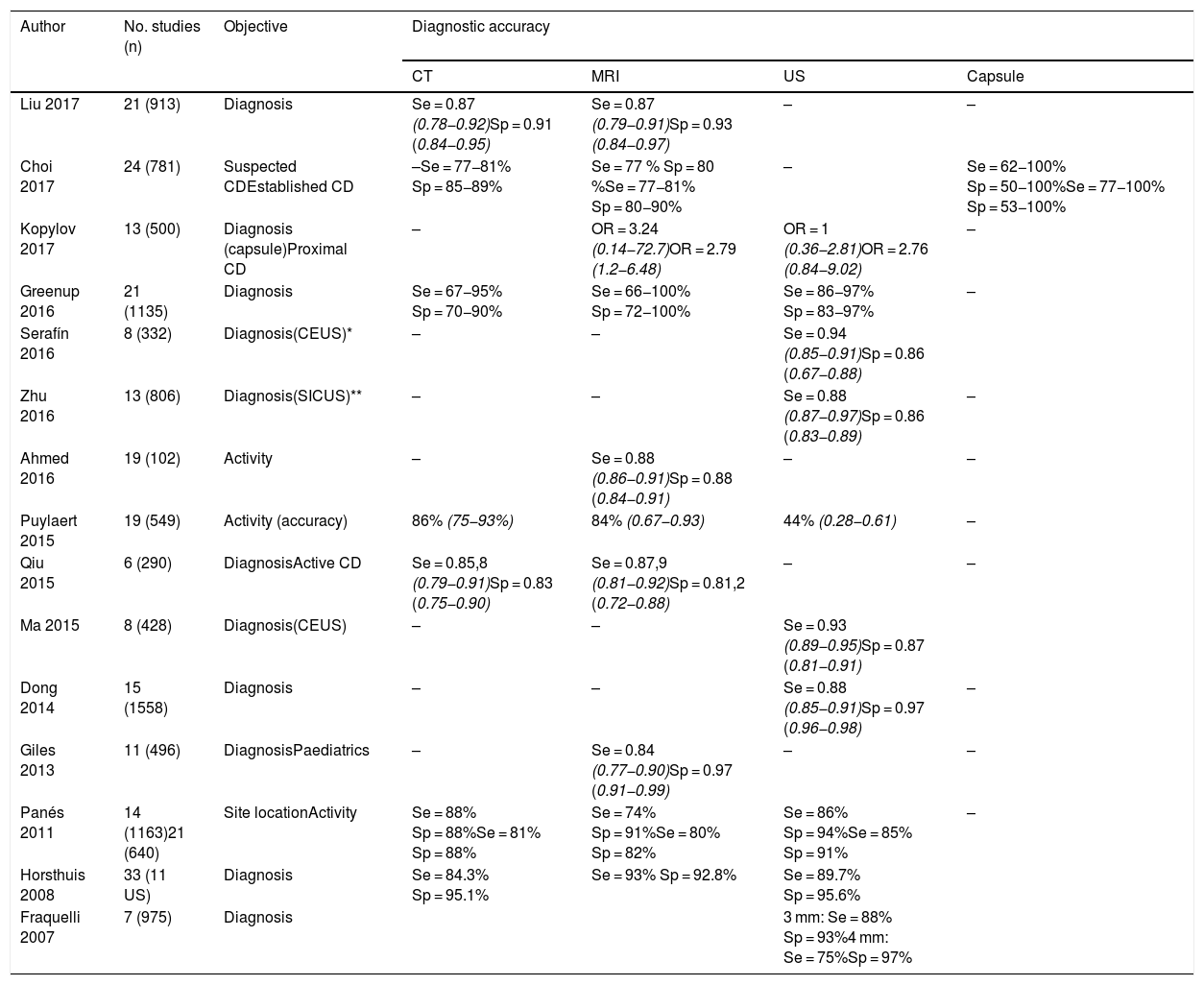

In published systematic reviews, ultrasound has a sensitivity of 85-97% for the diagnosis of CD and a specificity of 83-97%.10,27,40,41,50,80–82 Studies comparing ultrasound and MRI show performance to be similar12,54,55,83–86 (Table 2), although in the METRIC study, which was the most appropriate methodologically,55 MRI was 10% superior to ultrasound in determining the extent in the small intestine. However, at diagnosis, ultrasound provides immediacy and it is very likely that in centres with experience in intestinal ultrasound, the two techniques may be superimposable.

Diagnostic accuracy of intestinal ultrasound and other imaging techniques in meta-analyses and systematic reviews.

| Author | No. studies (n) | Objective | Diagnostic accuracy | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CT | MRI | US | Capsule | |||

| Liu 2017 | 21 (913) | Diagnosis | Se = 0.87 (0.78−0.92)Sp = 0.91 (0.84−0.95) | Se = 0.87 (0.79−0.91)Sp = 0.93 (0.84−0.97) | – | – |

| Choi 2017 | 24 (781) | Suspected CDEstablished CD | –Se = 77−81% Sp = 85−89% | Se = 77 % Sp = 80 %Se = 77−81% Sp = 80−90% | – | Se = 62−100% Sp = 50−100%Se = 77−100% Sp = 53−100% |

| Kopylov 2017 | 13 (500) | Diagnosis (capsule)Proximal CD | – | OR = 3.24 (0.14−72.7)OR = 2.79 (1.2−6.48) | OR = 1 (0.36−2.81)OR = 2.76 (0.84−9.02) | – |

| Greenup 2016 | 21 (1135) | Diagnosis | Se = 67−95% Sp = 70−90% | Se = 66−100% Sp = 72−100% | Se = 86−97% Sp = 83−97% | – |

| Serafín 2016 | 8 (332) | Diagnosis(CEUS)* | – | – | Se = 0.94 (0.85−0.91)Sp = 0.86 (0.67−0.88) | |

| Zhu 2016 | 13 (806) | Diagnosis(SICUS)** | – | – | Se = 0.88 (0.87−0.97)Sp = 0.86 (0.83−0.89) | – |

| Ahmed 2016 | 19 (102) | Activity | – | Se = 0.88 (0.86−0.91)Sp = 0.88 (0.84−0.91) | – | – |

| Puylaert 2015 | 19 (549) | Activity (accuracy) | 86% (75−93%) | 84% (0.67−0.93) | 44% (0.28−0.61) | – |

| Qiu 2015 | 6 (290) | DiagnosisActive CD | Se = 0.85,8 (0.79−0.91)Sp = 0.83 (0.75−0.90) | Se = 0.87,9 (0.81−0.92)Sp = 0.81,2 (0.72−0.88) | – | – |

| Ma 2015 | 8 (428) | Diagnosis(CEUS) | – | – | Se = 0.93 (0.89−0.95)Sp = 0.87 (0.81−0.91) | |

| Dong 2014 | 15 (1558) | Diagnosis | – | – | Se = 0.88 (0.85−0.91)Sp = 0.97 (0.96−0.98) | – |

| Giles 2013 | 11 (496) | DiagnosisPaediatrics | – | Se = 0.84 (0.77−0.90)Sp = 0.97 (0.91−0.99) | – | – |

| Panés 2011 | 14 (1163)21 (640) | Site locationActivity | Se = 88% Sp = 88%Se = 81% Sp = 88% | Se = 74% Sp = 91%Se = 80% Sp = 82% | Se = 86% Sp = 94%Se = 85% Sp = 91% | – |

| Horsthuis 2008 | 33 (11 US) | Diagnosis | Se = 84.3% Sp = 95.1% | Se = 93% Sp = 92.8% | Se = 89.7% Sp = 95.6% | |

| Fraquelli 2007 | 7 (975) | Diagnosis | 3 mm: Se = 88% Sp = 93%4 mm: Se = 75%Sp = 97% | |||

Once treatment is started in patients with CD, we have to assess whether or not the objectives have been achieved and, if they have, we need to periodically monitor for possible disease reactivation. It is recommended that the initial, endoscopic or transmural response should be assessed within the first six months after starting treatment.49 Ultrasound can be useful for monitoring at this stage. The main study in this regard is the prospective multicentre TRUST study, which included 234 patients followed up for 12 months. Practically all the parameters assessed (wall thickness, loss of layering, creeping fat, colour Doppler signal, lymphadenopathy and strictures) showed improvement as early as three months after starting treatment.47 Ultrasound changes can be seen even earlier, having been reported at four and even at two weeks.38,87,88 Ultrasound has an excellent correlation with endoscopic findings, and can provide a good estimate of mucosal healing.89 Of the different parameters, the one that best predicts mucosal healing is the colour Doppler signal (κ = 0.82; p < 0.001), with a sensitivity of 97.6% and specificity of 82.4%.

Transmural healing or complete disappearance of lesions implies a better prognosis than partial improvement in the medium-to-long term,90–92 and could even have a greater prognostic value than isolated mucosal healing.93 Around a third of patients with mucosal healing have persistent lesions on imaging techniques, but not all of these lesions have the same significance in terms of prognosis.93,94 With MRI, residual thickening, enhancement and the presence of strictures are associated with a higher risk of recurrence, but creeping fat is not.46,94

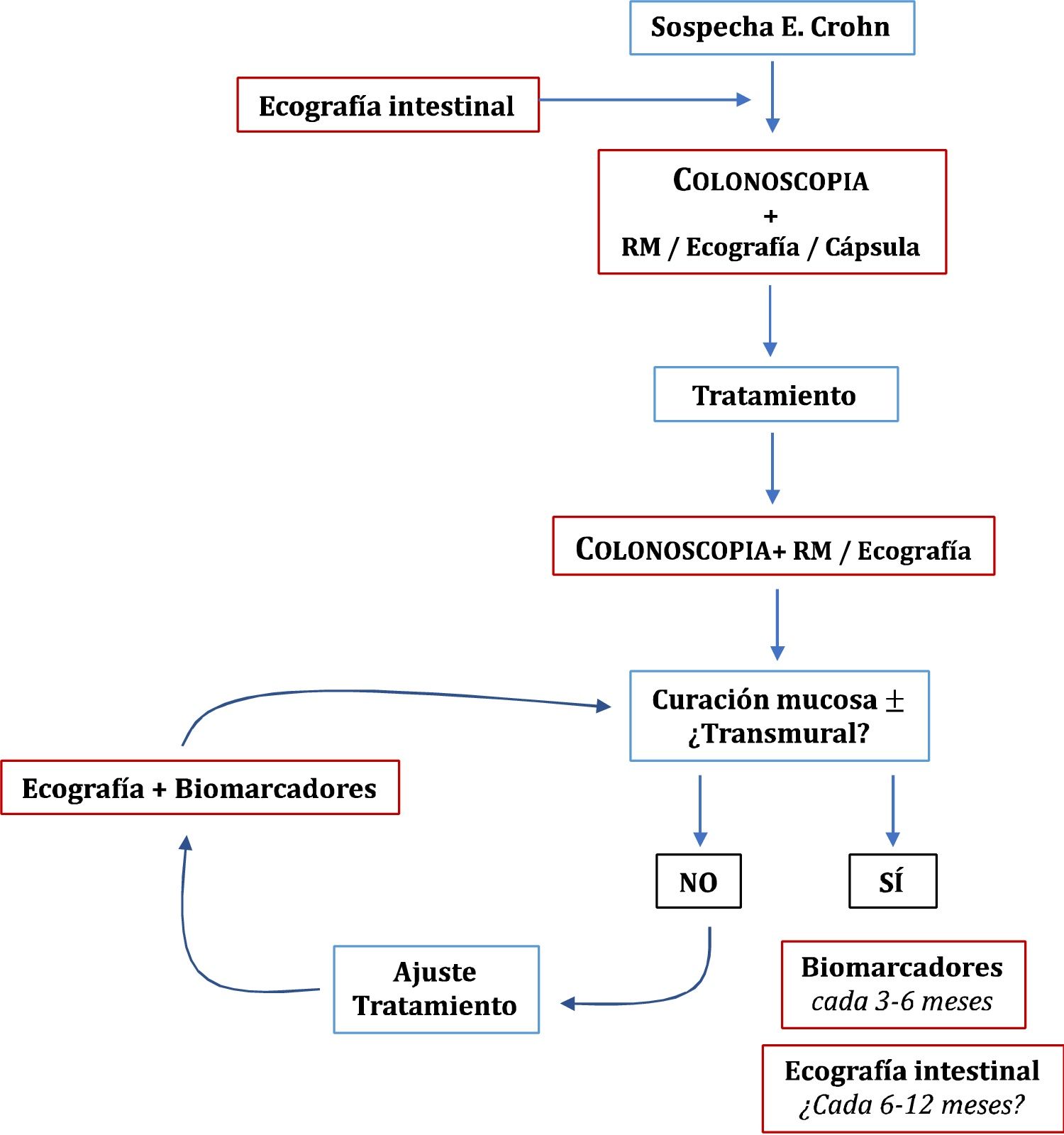

Once the treatment objectives have been achieved, the role of imaging techniques in the monitoring of patients with CD is mainly in cases of suspected recurrence or unexplained symptoms or before a significant change in treatment.49 Clinical signs and biomarkers are not exempt from false negatives, so some authors recommend an examination every 6–12 months.95 However, this has not been sufficiently explored in the specialised literature. In patients in remission and with normal CRP, up to 27% have ultrasound activity, which can change the doctor's clinical decision in 58-60% of cases.54 The role of ultrasound in the diagnosis and monitoring of CD is summarised in Fig. 1.

RecurrenceIleocolonoscopy is considered the technique of choice for the initial assessment and is advised 6–12 months after surgery,96 using the Rutgeerts index (iR) to evaluate and grade the findings.97 However, the lack of consensus on when the next ileocolonoscopy should be performed has led to ultrasound in conjunction with faecal calprotectin being proposed as valid non-invasive alternatives to ileocolonoscopy during the follow-up of the disease.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of ultrasound for detecting postoperative recurrence (POR) is 94% and 84% respectively.98–102 Wall thickness is the main parameter studied, and a neoterminal ileum thickness ≥3 mm is generally considered a sign of recurrence. The use of oral contrast improves sensitivity (99%), although with a decrease in specificity (74%)98. Another aspect studied is the detection of the severity of recurrence (iR ≥ i3). The cut-off value that best predicts severe recurrence (iR3-4) is thickness ≥5 mm, with a sensitivity of 83.8% and specificity of 97.7%.98 Other signs associated with severe forms of the disease are the extent of involvement of the neoterminal ileum and the presence of complications (fistulas, abscesses) or strictures.99,102–104 The grading of hyperaemia with colour Doppler ultrasound has been correlated with the degrees of severity of endoscopic recurrence.105 Studies with IV contrast improve the detection of severe forms of recurrence with a high positive predictive value (82-90%).102,103

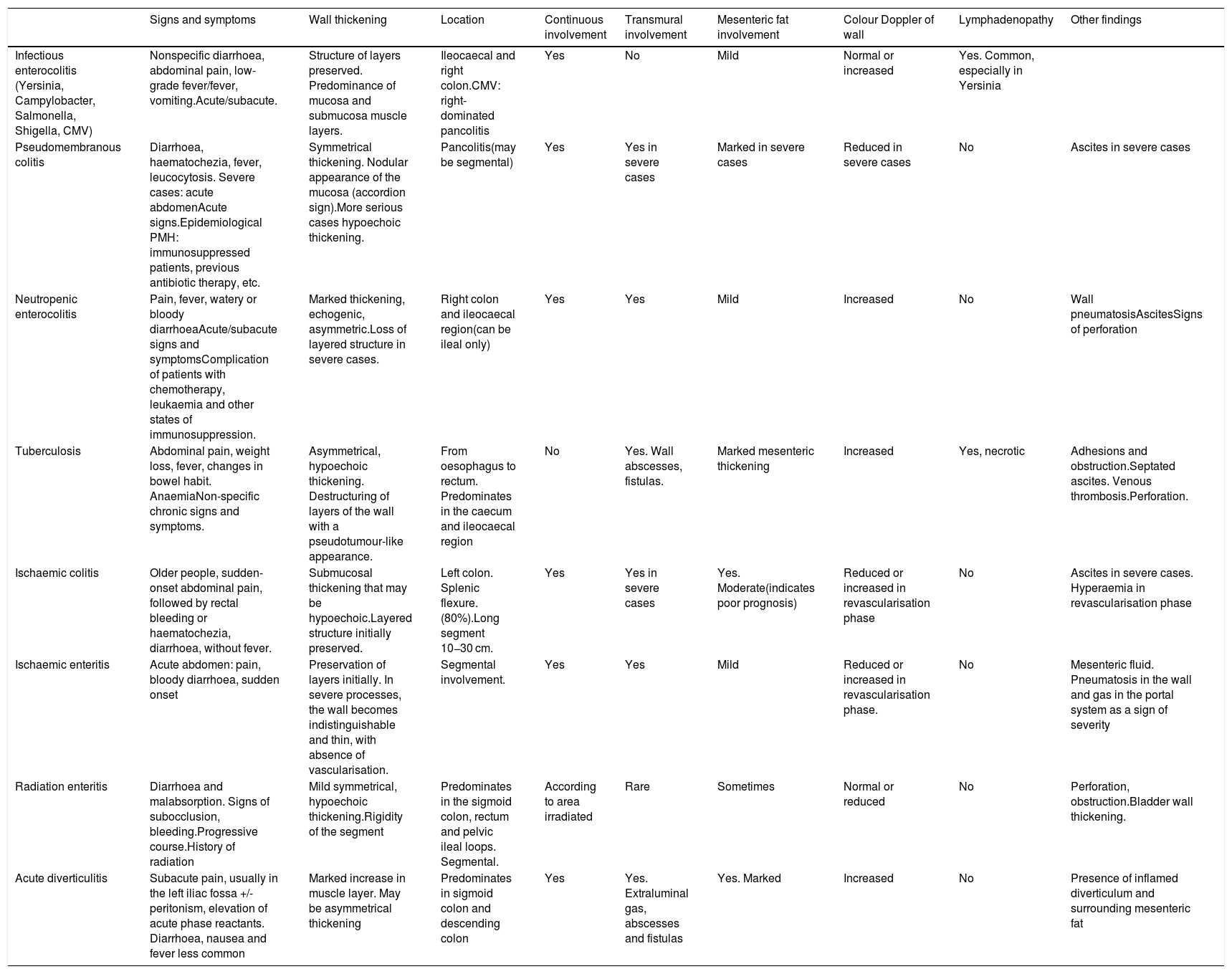

Differential diagnosisThe ultrasound findings of IBD described above can be identified in other diseases and the differential diagnosis can be complex at times. Thickening of the wall is one of the most common signs of bowel disease, but it occurs in many different conditions. It is the appearance of the wall echotexture, the location of the abnormality and other associated ultrasound findings that can help us to differentiate them. Also, in most cases the clinical presentation of the condition also helps establish the diagnosis of the disease (Table 3).

Main differential diagnoses of IBD.

| Signs and symptoms | Wall thickening | Location | Continuous involvement | Transmural involvement | Mesenteric fat involvement | Colour Doppler of wall | Lymphadenopathy | Other findings | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infectious enterocolitis (Yersinia, Campylobacter, Salmonella, Shigella, CMV) | Nonspecific diarrhoea, abdominal pain, low-grade fever/fever, vomiting.Acute/subacute. | Structure of layers preserved. Predominance of mucosa and submucosa muscle layers. | Ileocaecal and right colon.CMV: right-dominated pancolitis | Yes | No | Mild | Normal or increased | Yes. Common, especially in Yersinia | |

| Pseudomembranous colitis | Diarrhoea, haematochezia, fever, leucocytosis. Severe cases: acute abdomenAcute signs.Epidemiological PMH: immunosuppressed patients, previous antibiotic therapy, etc. | Symmetrical thickening. Nodular appearance of the mucosa (accordion sign).More serious cases hypoechoic thickening. | Pancolitis(may be segmental) | Yes | Yes in severe cases | Marked in severe cases | Reduced in severe cases | No | Ascites in severe cases |

| Neutropenic enterocolitis | Pain, fever, watery or bloody diarrhoeaAcute/subacute signs and symptomsComplication of patients with chemotherapy, leukaemia and other states of immunosuppression. | Marked thickening, echogenic, asymmetric.Loss of layered structure in severe cases. | Right colon and ileocaecal region(can be ileal only) | Yes | Yes | Mild | Increased | No | Wall pneumatosisAscitesSigns of perforation |

| Tuberculosis | Abdominal pain, weight loss, fever, changes in bowel habit. AnaemiaNon-specific chronic signs and symptoms. | Asymmetrical, hypoechoic thickening. Destructuring of layers of the wall with a pseudotumour-like appearance. | From oesophagus to rectum. Predominates in the caecum and ileocaecal region | No | Yes. Wall abscesses, fistulas. | Marked mesenteric thickening | Increased | Yes, necrotic | Adhesions and obstruction.Septated ascites. Venous thrombosis.Perforation. |

| Ischaemic colitis | Older people, sudden-onset abdominal pain, followed by rectal bleeding or haematochezia, diarrhoea, without fever. | Submucosal thickening that may be hypoechoic.Layered structure initially preserved. | Left colon. Splenic flexure. (80%).Long segment 10−30 cm. | Yes | Yes in severe cases | Yes. Moderate(indicates poor prognosis) | Reduced or increased in revascularisation phase | No | Ascites in severe cases. Hyperaemia in revascularisation phase |

| Ischaemic enteritis | Acute abdomen: pain, bloody diarrhoea, sudden onset | Preservation of layers initially. In severe processes, the wall becomes indistinguishable and thin, with absence of vascularisation. | Segmental involvement. | Yes | Yes | Mild | Reduced or increased in revascularisation phase. | No | Mesenteric fluid. Pneumatosis in the wall and gas in the portal system as a sign of severity |

| Radiation enteritis | Diarrhoea and malabsorption. Signs of subocclusion, bleeding.Progressive course.History of radiation | Mild symmetrical, hypoechoic thickening.Rigidity of the segment | Predominates in the sigmoid colon, rectum and pelvic ileal loops. Segmental. | According to area irradiated | Rare | Sometimes | Normal or reduced | No | Perforation, obstruction.Bladder wall thickening. |

| Acute diverticulitis | Subacute pain, usually in the left iliac fossa +/- peritonism, elevation of acute phase reactants. Diarrhoea, nausea and fever less common | Marked increase in muscle layer. May be asymmetrical thickening | Predominates in sigmoid colon and descending colon | Yes | Yes. Extraluminal gas, abscesses and fistulas | Yes. Marked | Increased | No | Presence of inflamed diverticulum and surrounding mesenteric fat |

The ultrasound findings very often do not allow us to differentiate IBD from other intestinal conditions, such as infectious ileitis. In such cases, if we perform an ultrasound 4–6 weeks after the acute process, we can verify the resolution of the ultrasound findings in infectious disease, while this would be uncommon in patients with CD.

Ultrasound in UCThe utility of ultrasound in ulcerative colitis (UC) is less established for several reasons: a greater correlation between clinical manifestations and endoscopic activity106; an adequate correlation of endoscopic activity with faecal calprotectin107; better accessibility to endoscopic assessment49; and, finally, because UC does not require imaging tests to monitor response to treatment.108 The ECCO guidelines do not recommend systematic assessment of the small intestine in patients with UC and only consider it when there is uncertainty over the diagnosis of UC or CD, as in cases with rectal preservation, atypical symptoms or reflux ileitis.109

Ultrasound does not allow adequate assessment of the rectum, so generally we will be able to identify disease proximally from the rectosigmoid junction, with varying degrees of extension. The most common ultrasound findings are continuous, symmetrical thickening of the bowel wall, irregularity of the surface of the mucosa, submucosal oedema, absence of haustra and wall hyperaemia.56,110 The thickness used for the diagnosis of UC is usually 3 mm in children111 and 4 mm in adults.56 Because the disease is not transmural, mesenteric fat involvement and loss of bowel wall echotexture are less common findings,112 although they may be present in severe flare-ups of the disease.57

Ultrasound has shown a high correlation with endoscopic findings in assessing the extent of the disease in UC, demonstrating its utility in patients who initially present with a severe flare-up, in whom colonoscopy is incomplete or limited, and in whom proximal extension is unknown.56,111,113

There is a high correlation between endoscopic activity and ultrasound findings,114–117 with wall thickness and wall hyperaemia being the most useful parameters.111,115–118

Learning the techniqueIt is commonly assumed that intestinal ultrasound has high interobserver variability and a high learning curve. However, in the main variables of activity, such as wall thickness and vascularisation, the correlation between examiners is excellent (k = 0.7–1 and 0.53−0.89 respectively).15 There has been very little study of the learning curve, with only one published paper stating that the number of examinations necessary to reach a degree of competence similar to someone with experience is in the range of 150-200.119 Previous experience in abdominal ultrasound speeds up the process and, although not essential to acquire the training, is helpful in terms of detecting other disorders that may be present.

ConclusionsUltrasound has similar performance to other imaging techniques such as MRI or CT, but with the added advantages of its wide availability and accessibility as well as excellent tolerance. It can be carried out at the "bedside" without preparation, allowing immediate identification of IBD and thus shortening the time to diagnosis. Ultrasound acts as a complement to colonoscopy in delimiting the extent and assessing the activity in the initial diagnosis of CD, and its tolerance allows the examinations necessary for close or "proactive" monitoring. It is able to diagnose complications associated with the disease such as strictures, fistulas and abscesses with a high degree of accuracy and, where necessary, guide the percutaneous drainage of such abscesses. Ultrasound also has a role in detecting recurrence after surgery, helping to avoid the need for endoscopic examinations. In UC, however, it has a more accessory role, as endoscopy is the main technique in the management of these patients, but it does help to define extent and activity when this is not possible with colonoscopy. Despite these advantages, the spread and implementation of its use in IBD units in Spain is limited. Promotion of and training in the technique are therefore essential to encourage more generalised incorporation of ultrasound into routine clinical practice.

RecommendationsIntroduction and advantages and disadvantages- •

For investigating CD, sectional imaging tests which make it possible to assess segments proximal to the terminal ileum and transmural lesions are recommended, to complement the findings of the colonoscopy.

- •

Intestinal ultrasound enables this assessment with a high degree of accuracy, both for diagnosis and monitoring, and provides additional advantages over CT (no radiation) and MRI (cost-effectiveness, tolerance, availability and accessibility).

- •

The examination can be performed without any prior preparation, although with planned examinations fasting for at least four hours is advisable.

- •

The use of high-frequency transducers (at least 5 MHz) is recommended to identify the layers of the bowel wall for the ultrasound assessment of the intestinal loops. The examination should include B-mode and colour Doppler in order to identify bowel wall hyperaemia.

- •

The examination can be complemented with the administration of oral contrast, for better assessment of strictures and loops proximal to the ileum.

- •

Intravenous contrast improves assessment of vascularisation of affected loops and is particularly useful in cases of abnormal thickening of the wall without wall hyperaemia, with colour Doppler, or in the presence of phlegmons or abscesses.

- •

For the diagnosis of CD, using a wall thickness greater than 3 mm is recommended to maximise sensitivity. If a higher diagnostic specificity is preferred, the value would be 4 mm.

- •

To assess EC activity, analysing the layered pattern of the bowel wall and checking for the presence of ulcers or creeping fat is recommended, as well as using colour Doppler to examine bowel wall vascularisation. IV contrast can be used in cases with bowel wall thickening in which the colour Doppler mode has not been able to detect hyperaemia.

- •

The use of ultrasound or MRI is recommended to determine the extent of CD.

- •

In cases of extensive involvement (>20 mm), an MRI is recommended, especially at diagnosis. In pre-surgical planning, an MRI should be considered if the findings are expected to be relevant, but it is not essential.

- •

If a stricture is suspected on ultrasound, administration of oral contrast is recommended to increase the accuracy of the diagnosis. Elastography and IV contrast can help characterise the predominantly inflammatory or fibrotic nature of the stricture.

- •

Ultrasound is recommended as the initial technique when an abscess or fistula is suspected, as it shows similar diagnostic accuracy to other techniques. However, in the case of deep or retroperitoneal abscesses, intestinal CT or MRI may be necessary.

- •

IV contrast is recommended in the event of an inflammatory mass, as it helps differentiate a phlegmon from an abscess and better defines the size of the abscess. Ultrasound with IV contrast is considered the technique of choice if percutaneous drainage and monitoring of abscess resolution are considered necessary.

- •

An early ultrasound scan (at 3–6 months) is recommended after the introduction of a new treatment in order to optimise the treatment.

- •

An ultrasound scan is recommended when symptoms occur and before changing treatment.

- •

Once the objective has been achieved, in asymptomatic patients and even if there us insufficient evidence, it could be advisable to use ultrasound monitoring every 6–12 months, depending on the severity and characteristics of the patients, to complement the information provided by the biomarkers.

- •

The use of ultrasound in conjunction with faecal calprotectin is recommended in follow-up of patients who have had surgery for their CD, after the initial colonoscopy.

- •

If the anastomosis cannot be distinguished, administration of oral contrast may be useful. IV contrast can be helpful in cases of wall thickening without wall hyperaemia in colour Doppler mode.

- •

With any gastrointestinal symptoms, ultrasound can be useful as the first diagnostic test. In the differential diagnosis with infectious ileitis, prior to a possible colonoscopy, we recommend repeating the examination at 4–6 weeks to check for resolution of the findings.

- •

In UC, ultrasound has a complementary role to colonoscopy. An ultrasound scan is recommended in cases where it is not possible to determine the extent of the disease (severe flare-ups, strictures, incomplete colonoscopy) or in cases of normal rectosigmoidoscopy with suspected proximal activity.

- •

Performing a sufficient number of supervised ultrasound scans, estimated at around 200, is recommended in order to reach the necessary level of training. Prior experience in and understanding of ultrasound is recommended and speeds up the training process.

- -

Fernando Muñoz: scientific advice and support for research and/or training activities from Tillots Pharma, Kern Pharma, Abbvie, Janssen, Pfizer and Takeda.

- -

Tomás Ripollés, Joaquín Poza Cordón, Berta de las Heras Páez de la Cadena and María Jesús Martínez-Pérez have participated in training activities sponsored by Abbvie.

- -

Enrique de Miguel: no conflicts of interest.

- -

Yamile Zabana: lecturer, consultant, advisory board or has received grants for research from: Abbvie, MSD, Ferring, Amgen, Janssen, Pfizer, Dr Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Shire, Takeda, Otsuka Pharmaceuticals and Almirall.

- -

Miriam Mañosa has received grants for research, training activities or consulting from MSD, Abbvie, Kern, Takeda, Janssen, Pfizer, Ferring, Faes Farma, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillots Pharma and Adacyte.

- -

Belén Beltrán: scientific advice and support for research and/or training activities from AbbVie, Otsuka, Pfizer, Takeda and MSD.

- -

Manuel Barreriro-de Acosta: scientific advice and support for research and/or training activities from MSD, AbbVie, Hospira, Pfizer, Kern Pharma, Biogen, Takeda, Janssen, Sandoz, Celgene, Ferring, Faes Farma, Shire Pharmaceuticals, Dr. Falk Pharma, Tillotts Pharma, Chiesi, Gebro Pharma, Otsuka Pharmaceutical and Vifor Pharma.

Please cite this article as: Muñoz F, Ripollés T, Poza Cordón J, de las Heras Páez de la Cadena B, Martínez-Pérez MJ, de Miguel E, et al. Recomendaciones del Grupo Español de Trabajo en Enfermedad de Crohn y Colitis Ulcerosa (GETECCU) sobre el empleo de la ecografía abdominal en la enfermedad inflamatoria intestinal. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021;44:158–174.