Infliximab is an anti-tumour necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) antibody used in the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Its use is associated with infectious and immunological pulmonary complications, including interstitial lung disease.1

We present the case of a 54-year-old male, an active smoker (15 pack-years), who has suffered from ileocolic Crohn's disease for 14 years. The patient required maintenance treatment with thiopurines for 46 months, but these were discontinued when he was shown to be in prolonged remission. Over the following nine months, he had a severe flare-up that was initially treated with intravenous methylprednisolone. Inflectra® (infliximab biosimilar), azathioprine and cotrimoxazole were later added for maintenance.

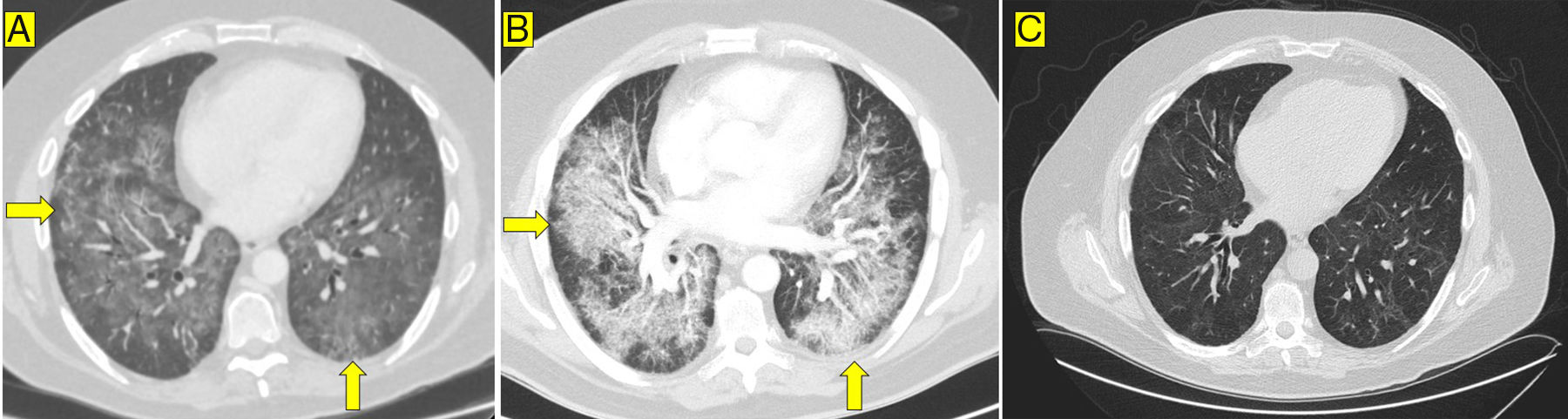

The patient consulted with chest pain and dyspnoea 18 days after receiving the second dose of infliximab. He was afebrile, but had tachycardia and tachypnoea. Arterial blood gases (oxygen via nasal cannula at 4l/min) showed: pO2=67mmHg, pCO2=37mmHg, bicarbonate=24mM/l. The only other relevant findings from blood tests were: C reactive protein=115mg/l (normal<5mg/l); d-dimer=900ng/ml (normal≤500ng/ml); and rheumatoid factor=54.1IU/ml (normal<40). Computed tomography (CT) angiography of the chest detected filling defects in the segmental pulmonary arteries and diffuse, bilateral, symmetrical lung involvement in a mosaic pattern (Fig. 1A). The echocardiogram and Doppler ultrasound of the lower limbs were normal. The patient was started on low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) 1mg/kg body weight every 12h. However, despite this, he suffered a severe deterioration of respiratory function and had to be transferred to Intensive Care. Repeat CT angiography showed radiological deterioration, with ground glass opacities and areas of septal thickening (Fig. 1B). Bronchoscopy study was negative for mycobacteria, Pneumocystis jirovecii, Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Aspergillus. With the diagnosis of suspected interstitial pneumonitis, piperacillin/tazobactam, cotrimoxazole and methylprednisolone were administered intravenously.

The patient gradually improved and was discharged with oral methylprednisolone, azathioprine, cotrimoxazole, LMWH and oxygen therapy. The infliximab biosimilar was discontinued and vedolizumab (anti-alpha-4 beta-7-integrin antibody) was prescribed to avoid the use of other anti-TNF-α drugs. Six months after discharge, oxygen therapy was discontinued and the peri-bronchial consolidation disappeared, but a non-specific mosaic pattern and minimal bronchiectasis persisted (Fig. 1C).

None of the other medications to which the patient was exposed during this period have been linked to the development of interstitial lung disease. Therefore, given that re-exposure would be both dangerous and unethical, we attribute the adverse event to the infliximab biosimilar.

In patients with IBD, the most common lung complications derive from the development of pulmonary thromboembolism1, as the extraintestinal manifestations of IBD rarely affect the respiratory system. Other complications, such as drug-related pulmonary toxicity (mesalazine, methotrexate, etc.), are less common.1

Among the non-infectious complications of infliximab is interstitial pneumonia. Although the incidence thereof is not known, in some registries it is estimated at around 2.9%.2 It is more common in males, older people and individuals with a previous history of lung disease or glucocorticoid use.3

There are few reported cases of patients with IBD and interstitial pneumonitis secondary to infliximab4 and we are yet to find one associated with an infliximab biosimilar.

A series of 122 patients with diffuse interstitial lung disease (DILD) associated with anti-TNF-α treatment was reported in Spain. Most of the patients were being treated for rheumatoid arthritis, with almost half receiving infliximab.5 DILD developed an average of 26 weeks after administration with symptoms of dyspnoea, fever and cough.5 Most patients were treated with corticosteroids, sometimes given in combination with other immunosuppressants, and the mortality rate was 29%.5

In our case, the patient made a good recovery from the lung disorder with corticosteroid treatment, and is now asymptomatic.

In conclusion, despite the fact that the most common complications are infectious, inflammatory lung involvement related to anti-TNF-α drugs should be suspected in case of respiratory symptoms or impaired gas exchange. This complication has been described with the reference drug infliximab and can also occur with the infliximab biosimilar. In order to ensure early diagnosis and management of this complication, it is important to stress that patients receiving anti-TNF-α drugs can develop DILD, particularly if they have risk factors.

The authors notified the SEFV (Sistema Español de Farmacovigilancia [Spanish Pharmacovigilance System]) about this case.

Please cite this article as: Ríos León R, Jaureguizar Oriol A, López-Sanromán A, Jiménez Castro D, Nieto Royo R, Albillos Martínez A. Toxicidad pulmonar aguda grave secundaria al uso de infliximab biosimilar en un paciente con enfermedad de Crohn. Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;42:104–105.