Early detection of psychiatric disorders in general hospital settings could facilitate a systematic assessment of anxiety and depression, and lessen their non-detection, misdiagnoses and subsequent negative impacts. We built a new short screening tool with simple Yes/No questions on anxiety and depression and examined its diagnostic capacity and acceptability.

MethodsOur cross-sectional study included 608 patients examined in an emergency department at a Parisian general hospital. Their depressive and anxiety symptoms were assessed with the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), and the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7). Participants also completed the ‘GHU-checklist’, a list of 17 words evoking moods or feelings. Sensitivity and specificity of the checklist were determined using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) analysis.

Results22.7% of participants had depressive symptoms as measured by the PHQ-9, while 25.4% suffered from moderate or severe anxiety. Most participants perceived positively the GHU-checklist, which had a sensitivity of 81.5% in distinguishing patients with depressive symptoms. Sensitivity was 86.0% for moderate anxiety and 94.7% for severe anxiety. The specificity ranged from 64.3% to 71.1%.

ConclusionsA short 17-words checklist is able to ultra-rapidly screen for depressive and anxiety symptoms in non-psychiatric medical settings, and was perceived positively by patients. Its systematic use could facilitate a rapid and systematic assessment of these symptoms, especially in crowded and under-staffed settings such as the emergency department.

Depressive and anxiety disorders are the most common and persistent mental health disorders, affecting 4.4% and 3.6% of the world population, respectively.1 They are one of the leading causes of disability worldwide and are major contributors to the overall global burden of disease.2,3 Depression is also one of the most consistent predictors of suicide risk.4Tools and programs capable of early detection and treatment of these common mental health problems have been reported to lessen their negative impacts by reducing symptoms and suicide risk.5

However, these disorders are too often undetected or under-detected, especially in primary care and general emergency departments,6 leading to an important proportion of affected patients leaving these settings without proper referral or care.

The prevalence of anxiety and depression is especially high among patients visiting emergency departments (ED) for non-psychiatric conditions. In a study carried out in 14 European ED in 2011, nearly half of patients presented symptoms of anxiety (47%), and 23% had symptoms of depression, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS).7 More recent studies have also reported higher rates of depressive and anxiety symptoms among ED patients compared to the general population.8,9 In fact, mental health problems are a risk factor for repeated ED visits.10 Anxiety disorders are also associated with increased healthcare utilization across multiple care settings.11

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has resulted in a substantial increase in the prevalence of major depressive disorders and anxiety disorders.12 Access to mental health care was also severely hindered due to the pandemic, significantly increasing unmet mental health needs.13

Several validated self-administered questionnaires designed to screen for depressive and anxiety symptoms in the general population exist and have been previously used in primary care settings and in the ED.14,15 Nevertheless, these tools are time-consuming and are rarely used in routine practice. Efforts to promote early detection of depressive and anxiety disorders in ED as well as in other primary care settings are hindered by the low self‐confidence of care providers in their skills and training to detect mental health problems.16 In often crowded and under-staffed contexts, care providers also perceive that time-consuming mental health acts are not a top ED priority.17

To face these challenges, we developed a simple, short, “inconspicuous”, and self-administered screening tool to detect anxiety and/or depressive symptoms. In this study, we examine the usefulness and acceptability of this simple 17-word mood adjective checklist for screening anxiety and depressive disorders in an ED.

MethodsSetting and participantsOur observational study took place in the ED of the Bichat Claude-Bernard University general Hospital (Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris, Université de Paris), located in the north of Paris, France. It was carried out by the Parisian University Hospital Group (GHU) of Psychiatry and Neurosciences in collaboration with the Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Paris. Participants were recruited in the waiting areas of the ED, from March 7 to July 6, 2018, by a clinical research assistant, during the daytime (9 am to 5 pm), two days a week, Monday to Friday. Patients were eligible if they were 18 years of age or older, not suffering from a life-threatening condition, and willing to participate in our study. Patients were excluded from the study if they were unable to understand French, if their medical condition was incompatible with questionnaire administration (patients physically unable to read or write, for example), or if they objected to study participation. Age, sex, and reason for non-inclusion were collected on a separate register. All participants received a briefing note explaining the study objectives and were informed of their right to oppose study participation according to the French regulation and study protocol.18

Data collectionThe research assistant explained the study to all potential participants, and if they agreed to participate they were asked to fill in a paper self-administered questionnaire.

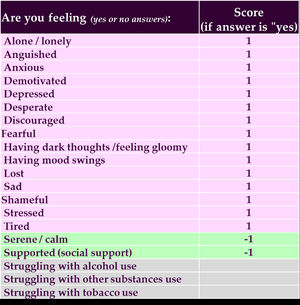

The GHU checklistA single question, “How have you been feeling these past two weeks?” was used to ask participants to describe their main mood(s) and feeling(s). The patient answered by choosing “yes” or “no” to the GHU-checklist of 17 words or short expressions that evoke signs of anxiety or depression, like “stressed”, “sad”, “calm” etc. (Fig. 1). Three questions on substance use were also included in the checklist (20 in total).

This list was based on expert opinions and an exploratory survey. First, several expert psychiatrists from Paris University had pre-selected a list of words and short expressions figuring in the DSM diagnostic criteria for depression/anxiety. This list was compared with results from an exploratory survey where a dozen psychiatric inpatients were asked to list three words describing their mood or symptoms during the two weeks preceding their hospital admission. The final list was obtained by combining the pre-selected list and the most frequently used words given by patients in the exploratory survey. We then added two “positive” mental health items corresponding to serenity and calmness, which differentiate between anxiety, depression, and a normal state.

Mental health assessmentOverall mental health, as well as depressive and anxious symptoms, were assessed using two validated instruments.

Depressive symptoms in the past 2 weeks were measured by using the Patient Health Questionnaire 9 (PHQ-9; score range from 0 to 27), with a cut-off point ≥10.19 For each participant who had up to 2 missing items with missing values, we imputed missing values with the mean score for all complete data for this score (n=57; 9.6%).

Anxiety level was measured by using the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7 (GAD-7), which distinguished “moderate anxiety” (GAD score between 10 to 14) and “severe anxiety” (GAD score ≥15) .20 We also imputed up to 2 missing items with missing values with the mean score for all complete data for this score (n=30; 5.1%).

Additional informationTo examine the main demographic characteristics of our participants, the auto-questionnaire also collected information on age, sex, living status, education level, and employment status.

We also collected data from medical records on emergency triage classification, which ranks conditions from least urgent5 to most urgent1.21 We also collected data on the reason for admission, and history of psychological or psychiatric follow-up.

Data on substance use was collected as complementary data of the 17-items checklist.

Patients feedbackPatients’ perceptions concerning the checklist were collected. Participants were asked whether they ever had the opportunity to fill out this questionnaire or a similar one, as well as its perceived usefulness. They were also asked about perceived difficulties or ease in completing and understanding the questions, and whether the words in the checklist reflected their feelings. They were also asked about possible discomfort with some questions. Open-ended commentaries were also possible.

Data and statistical analysisThe GHU-checklist scoreWe created a score based on participants’ answers to the 17- items on the checklist. A response was valid if a participant had answered “yes” to at least one of the items. Each missing value was considered as a “no” answer. Each “yes” response was given a value of 1 point. We then constructed a score by summing the points for all items except for the two related to feeling “calm” or “serene”, which were subtracted (Fig. 1). Therefore, the score had a possible range of -2 to 15.

AnalysisPatients’ characteristics were described for all included participants. Categorical variables were described by proportions (%); and continuous variables by means and their standard deviation. The age and sex distributions in patients included and excluded from the study were compared using the t-test and the chi-square test, respectively.

Receiver Operating Curve (ROC) plot curves allowed the calculation of an optimal cut-off point using the SAS macro %ROCPLOT using the Youden index,22 which allowed the creation of a binary variable characterizing those at risk of depressive or anxiety symptoms (yes/no).

Using the newly binary scale, we calculated sensitivity (Se), specificity (Sp), positive predictive value (PPV), and negative predictive value (NPV) to assess the diagnostic capacity of the dichotomized score.

Analyses were performed using SAS9.4® software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary NC). Statistical significance was determined at the .05 level of confidence.

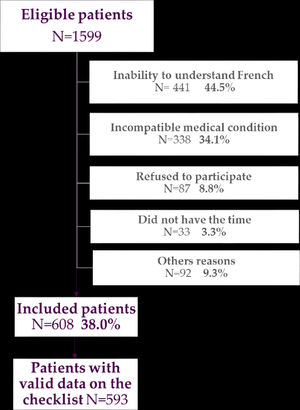

ResultsParticipants characteristicsOf the 1599 potential participants admitted to the ED on the days of survey administration, 608 (38%) were included in our study, with valid data for 593 patients. The study's flow chart indicating reasons for non-inclusion is presented in Fig. 2. Among eligible patients, 44.5% were excluded because they did not understand French well enough to be informed about the study and to self-complete the questionnaire (the hospital is based in a very ethnically-diverse geographic location), 34.1% due to either life-threatening or serious medical condition, or a condition which did not allow them to give informed consent and fill out the questionnaire, and 9.3% for other reasons (including unreturned questionnaires for 6.9% patients). Non-included patients were significantly older, with a mean age of 46.4 years (sd=17.3 years, p<0.001), and were more often men (62.5%, p<0.001) than included participants.

The socio-demographic, medical, and clinical characteristics of participants are described in Table 1. The mean age of participants was 42.2 years (sd=16.5), the majority were men (53.5%). Most participants were consulting for non-psychiatric reasons (98.2%) and were classified in level 4 (44.1%) or 5 (39.3%) of emergency triage, which corresponds to a stable medical situation, requiring medical care within 120 to 240 minutes. A history of psychiatric or psychological follow-up concerned a quarter of patients (n=155, 25.5%).

Socio-demographic and medical characteristics of patients in the emergency department.

Comparison of patients according to the GHU-checklist score. N=593

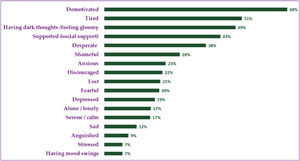

Fig. 3 presents the selection frequency for each item on the checklist. Most participants had checked at least one word or expression in the list (97.5%), with the most selected words being: « tired » (n=402, 67.8 %), « supported » (n=302, 50.9%), « stressed » (n= 288, 48.6%), “calm” (n=255, 43.0%), and « anxious » (n=223, 37.6%). Whereas «having dark thoughts » (n=53, 8.9%), « desperate » (n=40, 6.8%), and « with a sense of shame » (n=40, 6.8%) were the less selected items.

The average score was 2.6 (sd=3.9; min=-2; median =2; max =15).

Diagnostic capacityAbout 80% of all participants had completed data for the PHQ-9 (79.8%, n=485), and the GAD-7 (80.4 %, n=489) scales, and were therefore included in the tests assessing the diagnostic capacity of the GHU-checklist score.

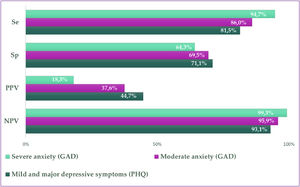

The optimal cut-off point on the GHU-checklist score calculated by the Youden index was different for the two mental health assessment tests. The Youden index was 4 for mild and major depressive symptoms (PHQ), and moderate anxiety (GAD), and 6 for severe anxiety (GAD). Therefore, we used the lowest cut-off point (<4) to dichotomize the score.

Fig. 4 shows the results of the different diagnostic tests for the newly binary GHU-checklist scale. The capacity of this scale to distinguish patients with overall mental health problems, moderate and severe anxiety, as well as mild and major depressive symptoms was rather high, with sensitivity varying from 81.5% (for mild and major depressive symptoms) to 94.7% (severe anxiety). The specificity varied from 64.3% (for severe anxiety) to 69.5% (moderate anxiety).

AcceptabilityMost patients (n=399, 65.5%) had a favorable opinion of this questionnaire. For almost one in four patients, answering this questionnaire allowed them to express difficulties they did not previously have the opportunity to voice (n=122, 22.9%). It was perceived as easy to complete for 80.9% of patients, easy to understand for 68.3% (n=415), interesting (n=334, 54.9%) and conveyed well their feelings for 52.6% (n=320).

DiscussionKey resultsIn this study, a simple 17-word mood adjective checklist displayed high sensitivity in detecting depressive symptoms and anxiety, and good acceptability even among patients not consulting for psychiatric reasons.

InterpretationOur screening tool has the potential to be used systematically in ED and other medical settings, and assist in optimizing the design of interventions that would reduce the escalation of mental health problems into more long-term problems, and decrease suicide risk.

This short and practical psychiatric screening tool could be made available for non-mental health clinicians in a context of increasing prevalence of depressive symptoms and anxiety, which often go undetected,6 and an ever-increasing time pressure on busy ED staff. . This tool could constitute another systematic emergency department test, along with, for example, blood pressure and sugar testing. A positive screening with this GHU-checklist should lead to a more detailed and precise psychiatric assessment and referral.

Our results corroborate those of other studies on the usefulness of short assessment tools for the detection of mental disorders in a non-psychiatric health care setting. Some studies compared standardized scales with simple questions, such as "are you depressed?”,23 and “Have you felt depressed or sad much of the time in the past year?”.24 These questions had slightly higher specificity than our checklist, but significantly lower sensitivity, the latter being arguably more important for screening tools.

Another mood adjective checklist has also been used for the assessment of anxiety and depression,25 but it is much longer (consisting of 132 adjectives) and has never been tested among patients not consulting for psychiatric reasons, such as ED patients. Most (97.5%) of participants checked at least one item on the list, which shows that the checklist is easy to understand and its use seems adapted to the emergency context or other non-psychiatric medical settings. Patients also had a positive reaction to the screening tool, and felt “heard” while waiting to be treated. This screening tool could therefore prompt a more complete psychiatric assessment for patients with potential psychiatric problems, and adequate care. Moreover, our checklist contained two items with a ‘positive’ connotation, which improved sensitivity and specificity.

LimitationsFindings from this study should be interpreted with the following limitations: The first limitation is potential selection bias. The main exclusion criteria were having a life-threatening medical condition and inability to understand French, which means our sample is not representative of all ED patients. Also, we observed a difference in age and sex distribution between included and non-included participants, and we did not include patients visiting at night or during the weekend.

Furthermore, because the study was conducted in a hospital in the north of Paris with relatively young patients who are multicultural and more socio-economically vulnerable than the rest of the Parisian population,26 the generalizability of our findings may be limited.

Future research in other geographical areas and/or in other medical settings would be pertinent.

To our knowledge, our checklist tests the first ultra-rapid screening tool on un-selected patients who were consulting for non-psychiatric reasons.

Moreover, our objective was not to describe the prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms among our study sample, but to compare our screening instrument to two other validated scales.

Another potential limitation is incomplete data, for around 20% of participants, on mental health scales serving as gold standards in the tests assessing the diagnostic capacity of the GHU-checklist score. However, the difficulties patients have in filling in the validated scales highlight the need to put in place simpler tools such as the GHU 17-items checklist. It is usual to have incomplete data in real life settings, especially concerning mental health measurement. Our screening checklist could limit such bias.

ImplicationsWe demonstrate the usefulness of a simple, non-invasive 17-items checklist, able to screen for anxiety and depressive symptoms in non-psychiatric medical settings. Our screening tool could be easily self-administered in often overcrowded ED as well as in other non-psychiatric medical settings such as general medical waiting rooms, where practitioners have limited time and where psychometric scales could be unsuitable. Our checklist could therefore improve the identification of affected patients and increase referrals to psychiatrists, potentially contributing to reducing suicide risk. It could also be used in automated admission forms.Ethical considerations

The study protocol was approved by an ethical committee (CPP Sud Est V) on November 23rd 2017 (IDRCB number: 2017 – A02974-49). Informed consent was obtained from all participants.