Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs) are alternative to incarceration programs for veterans involved in the criminal legal system. VTC participants have high rates of co-occurring mental health and substance use disorders (COD). Maintaining Independence and Sobriety Through Systems Integration, Outreach and Networking – Criminal Justice (MISSIONCJ) is an evidence-based, multicomponent intervention offered alongside VTCs to support veterans’ complex needs. Multicomponent interventions are often difficult to implement nationally, let alone when care is offered and coordinated across multiple systems. This protocol offers an overview of an implementation-effectiveness trial of MISSIONCJ in VTCs.

MethodsThis quality improvement (QI) project will involve an adaptive, randomized design, in which VA staff in four geographically-dispersed regions across the U.S. will be invited to participate and receive varying implementation facilitation (IF) support (i.e., low/passive and high/active) for implementing MISSIONCJ. Sites will have a 9-month run-in period (e.g., orientation) followed by 9-months of low/passive IF. Sites that meet an implementation benchmark will then be randomized to continue low/passive IF or discontinue; and sites that do not meet the benchmark will be randomized to continue low/passive IF, or receive high/active IF for 12-months. Implementation outcomes are based on the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance) framework (e.g., reaching eligible veterans, adoption rates, fidelity to MISSIONCJ, and maintenance/sustainment). MISSIONCJ effectiveness outcomes include treatment engagement and COD improvements.

DiscussionThis QI project aims to determine the most effective type and intensity of IF to increase MISSIONCJ, while improving outcomes among VTC participants. As the first national trial to implement MISSIONCJ in VTCs, it has important implications for the criminal legal and implementation science fields.

Trial RegistrationISRCTN registry, ISRCTN13576289, Registered 21 December 2022, https://www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN13576289

Veterans have high rates of criminal legal involvement with a 71 % increase over the past two decades.1-3 Nearly 60 % of veterans with criminal legal involvement have a co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder (COD),4-7 which is often associated with high rates of morbidity and mortality.8 Although little research has explicitly investigated the etiologic factors that explain the relationships between veteran status, criminal legal involvement, and COD, one systematic review and meta-analysis examining Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) and criminal legal involvement indicated that veterans with PTSD were at higher risk of criminal legal involvement compared to those without PTSD.9 Alternative to incarceration programs have been developed over the past two decades to reduce jail and prison overcrowding while referring participants to community-based substance misuse, mental health, and other needed behavioral health and social services.10-13

Veterans Treatment Courts (VTCs) are one type of national alternative to incarceration program, are designed specifically for veterans who served in the armed forces.14 VTCs operate through a partnership in which local courts initiate, fund and conduct a special court session for veterans, and the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Veterans Justice Outreach (VJO) program, provides staff to help with referrals and linkage support both in and out of the VA healthcare system. Fragmented care between VTCs and VA and non-VA behavioral health and social service programs is always a concern in these partnerships. This is particularly a concern for participants with a COD, as they often have multiple behavioral health and social determinants of health (SDOH) needs while facing challenges in engaging in treatment.15,16 Poor engagement can result in ongoing substance misuse, mental health symptom exacerbations, and a spiraling into unemployment and homelessness, which are strong predictors of recidivism.7,17 Therefore, VTC participants with a COD could benefit from robust and comprehensive wraparound services to help them remain engaged in VTCs, as well as VA and non-VA services.6,18

Maintaining Independence and Sobriety through Systems Integration, Outreach, and Networking-Criminal Justice (MISSIONCJ), is such an intervention that could be used by VJO staff to serve VTC participants with a COD. Moreover, MISSIONCJ, delivered by case manager and peer specialist teams is a multicomponent, cross disciplinary, evidence-based intervention, designed to engage veterans with a COD in care and reduce service fragmentation, and has been tested in alternative to incarceration settings.19-23 Unfortunately, despite being shown to improve outcomes, systems do not easily adopt new practices.24 This is particularly true for multicomponent interventions like MISSIONCJ as well as for complex settings such as VTCs given the need for close collaboration between the state criminal legal system, and the VA and non-VA service programs.25-27 Other studies have also confirmed that factors at both the individual level (e.g., training, skills, efficacy, and involvement in decision making) and organizational level (e.g., organization size, climate, financial resources, and active support for evidence-based practices among staff and administrators) predict successful implementation of evidence-based interventions.28-33 Implementation strategies at both the individual and organizational levels are needed to encourage adoption, since passive approaches such as training alone often result in little uptake of the evidence-based intervention.28,34-36

Implementation facilitation is a multi-faceted, context-specific process of enabling and supporting individuals, groups, and organizations in their efforts to adopt and incorporate clinical innovations, such as MISSIONCJ, into routine practices.26,37 Implementation facilitation can incorporate many implementation strategies, such as audit and feedback, education and training, and stakeholder engagement.37,38 However, optimal application, timing, and intensity of implementation facilitation across the lifespan of an implementation project is still unclear. One study suggests that a cost-effective approach to implementation support includes step-up support for slow responders as compared to simply starting high or low.39 This is crucial given that 96 % of sites discontinued prior to beginning pre-implementation, meanwhile fewer than 10 % of sites who implement a program/practice continue to sustain it beyond two years.40,41 As a result of steep early discontinuation of implementation efforts, Smith and colleagues (2018) suggest that providing early enhanced implementation facilitation support to sites with substantial organizational barriers may be wasted efforts unless they are tailored to leverage local contextual factors.42 Therefore, taking previous research into consideration, this quality improvement (QI) project will: 1) offer all sites low/passive implementation facilitation support and then randomize sites to different intensities of implementation facilitation for getting MISSIONCJ into practice among VJO staff working within VTCs; and 2) test effectiveness outcomes, including treatment engagement and COD improvements among veterans that received MISSIONCJ.

Materials and methodsAimsThe primary aim is to (a) identify pre- and post-implementation barriers and facilitators to adopting MISSIONCJ, and (b) assess the implementation effectiveness of varying intensities of implementation facilitation for getting VJO staff to deliver MISSIONCJ to the veterans they serve in VTCs. The secondary aim is to evaluate MISSIONCJ effectiveness via treatment engagement as well as mental health and substance use outcomes among veterans being served by VJO staff delivering MISSIONCJ in VTCs.

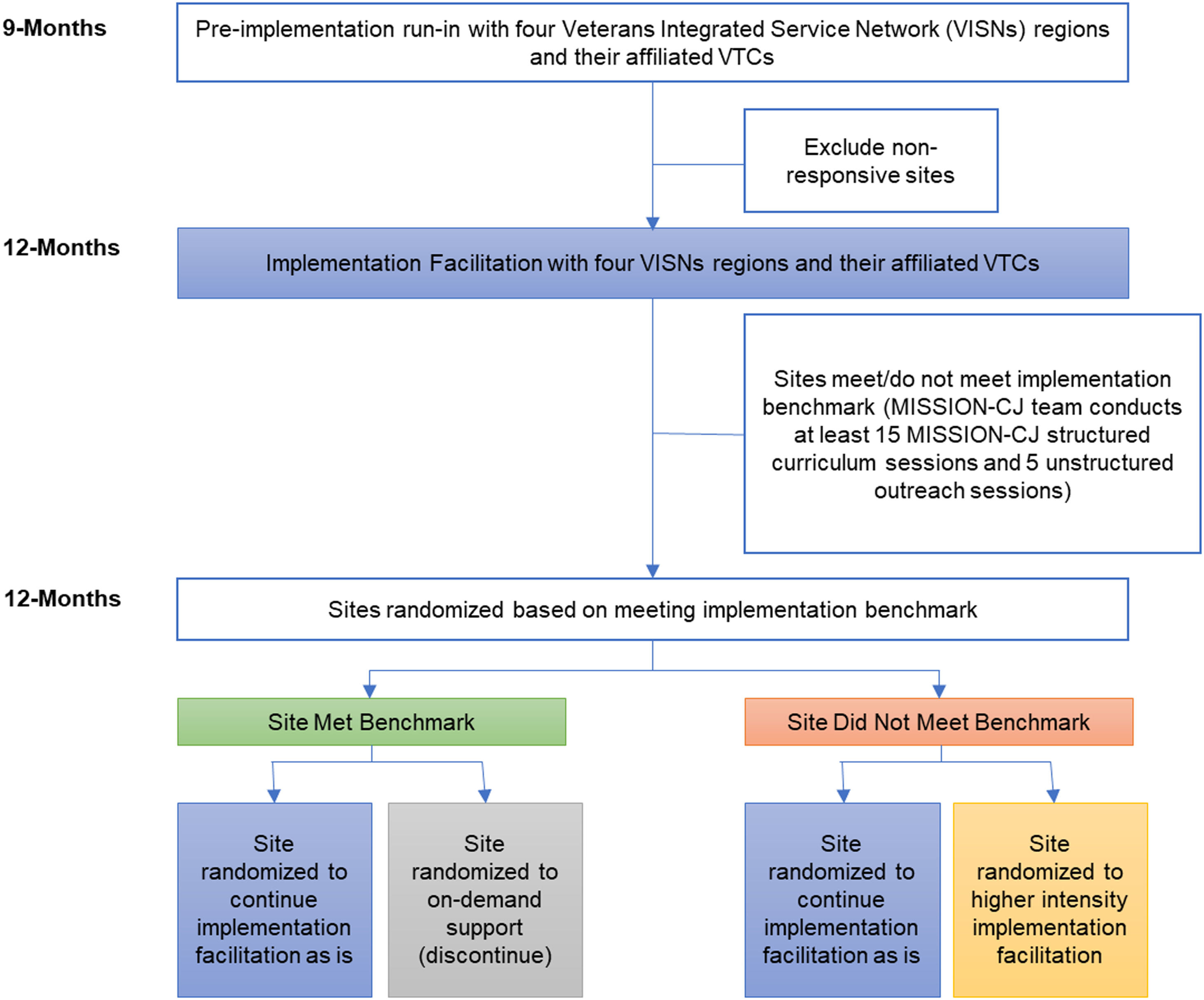

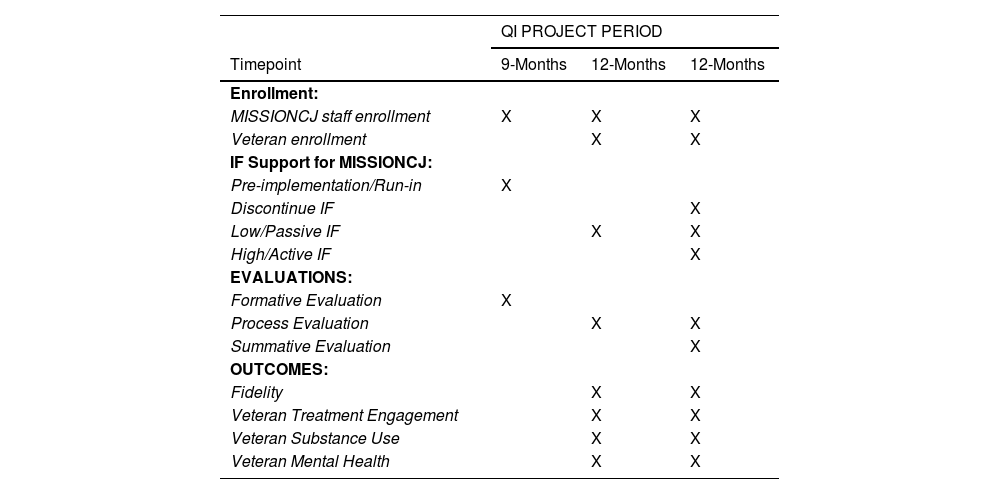

DesignWe selected a Hybrid Type III43 implementation-effectiveness, randomized, adaptive design (see Fig. 1 for an overview of the QI project design). First, there will be a pre-implementation run-in period of 9-months. This was selected to offer sites time to introduce MISSIONCJ to both the VJO staff and the affiliated VTC, modify any existing procedures for the partnership between the VJO program and VTC for delivering MISSIONCJ, and to get a MISSIONCJ treatment note within each partnering VA's medical record so that we could track MISSIONCJ service delivery type and frequency by VJO staff delivering MISSIONCJ to VTC participants. Then, sites will receive 9-months of low/passive implementation facilitation. At the end of this period, there is a predefined implementation benchmark that will play a role in the adaptive design of the randomization. Meeting the implementation benchmark is predefined as conducting at least 15 MISSIONCJ structured curriculum sessions (i.e., a combination of Dual Recovery Therapy (DRT), Empowering Prosocial Change (EPC), and/or Peer Support) and five unstructured outreach sessions during the 9-months of low/passive implementation facilitation. When they meet this predefined benchmark, they will be randomized using a SAS Macro. Those meeting the implementation benchmark will be randomized to either continue to receive low/passive implementation facilitation or discontinue for 12-months. If these components are not met, then sites will be considered as not meeting the implementation benchmark. Those not meeting the implementation benchmark will be randomized to either continue at the current intensity of implementation facilitation (i.e., low/passive), or to receive more personalized facilitation support (i.e., high/active intensity implementation facilitation) for 12-months. Implementation-effectiveness of the MISSIONCJ intervention is a secondary aim in this trial and will examine whether veterans demonstrate improved engagement and behavioral health outcomes when receiving MISSIONCJ. Table 1 provides an overview of the schedule of enrollment, implementation facilitation support, and assessment during the QI project period.

SPIRIT: Schedule of enrollment, implementation support, and assessment.

Note. IF = implementation facilitation.

The project is funded by the VA Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI, QUE 20–017), which is a quality improvement funding arm of VA. According to the VA Program Guide 1200.01, projects are considered quality improvement when; 1) the goal of the work is to improve VA care or processes, 2) data on performance is fed back to the provider or other levels of VA leadership in order to improve care, and 3) the work is funded in VA by care dollars as opposed to research dollars. Such activities go through an extensive review process for approval that includes a determination of non-research. This project met the aforementioned requirements and went through a review by the VA Bedford Healthcare System Institutional Review Board (IRB),44,45 the U.S. version of a research ethics committee, where it was deemed “non-research, quality improvement”. However, while such quality improvement efforts do not require the participants, in this case VA staff, to document informed consent, projects do ensure verbal consent, through a team member explaining the project procedures that are required to assist them with delivering the MISSIONCJ intervention. Participants are verbally asked for assent to participate and explicitly told that a lack of participation will have no impact on their employment at the VA.

VA setting and participantsThis QI project will invite VJO staff from multiple VA Medical Centers from four geographically dispersed Veterans Integrated Service Network (VISN) regions across the U.S. (i.e., VISN 1: VA New England Healthcare System; VISN 4: VA Healthcare – VISN 4; VISN 19: Rocky Mountain Network; and VISN 21: Sierra Pacific Network, and their affiliated VTCs (multiple per VA)). The VAs are similar in size, but the affiliated VTCs vary in respect to size, structure, and maturity. The VA sites are the unit of randomization in this trial. Each VA site has numerous VJO staff (i.e., case managers) assigned to VTCs. To fulfill the MISSIONCJ peer specialist role, the national VJO program created an opportunity for VA sites to apply for funding for dedicated paid peer specialist positions to work exclusively on this QI project in their respective VTCs to support the adoption and implementation of MISSIONCJ. A trained implementation facilitator will work with each VA site during the pre-implementation/run-in period to secure this funding and hire a new peer, or to secure a local peer.

Inclusion criteria for veterans being served by VJO staffTo identify veterans eligible for MISSIONCJ, VJO staff, who include licensed clinical case managers, review the VA medical record of veterans on their VTC caseloads for the following inclusion criteria: (1) VA service-connected and enrolled in a VTC affiliated with a VA site within one of the four regions (VISNs); (2) meets Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th Edition46 diagnostic criteria of International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision47 for a current substance use disorder(s) (mild – severe) and a co-occurring mental health disorder(s) (including anxiety, mood, or a psychotic spectrum disorders); and (3) is willing to participate in MISSIONCJ services. VTC enrollment varies and can be as high as 45 veterans per VTC, but we anticipate a more conservative 30 Veterans per VTC. With 10 total VTCs across all the project sites, we anticipate serving roughly 300 Veterans. We conducted power analysis for our effectiveness outcomes (Aim 2) based on this anticipated sample size. Specifically, we used GLIMMPSE, an online power computational tool specifically for conducting power analysis of the linear mixed effects models we plan to use in our effectiveness analysis.48 Assuming an alpha of 0.05, our anticipated sample size would have yield greater than 80 % power to detect a small-to-medium effect size.

MISSIONCJ clinical interventionMISSIONCJ is a 6-month, multicomponent, cross disciplinary, COD treatment intervention rooted in the Risk, Need, Responsivity49 and Health Belief Models.50 The three core service components of MISSIONCJ include 1) Critical Time Intervention (CTI), 2) an integrated co-occurring mental health and substance use disorder treatment called Dual Recovery Therapy (DRT) that includes an additional seven Empowering Prosocial Change (EPC) exercises (total of 20 sessions), and 3) Peer Support. The first component, CTI, is time-limited assertive case management model intended to provide proactive community outreach to help individuals engage in needed community services.51 While VJO programs offer linkage support, this would require them to expand their role to provide more intensive and comprehensive wraparound support which is delivered in three phases of decreasing intensity: Transition to Community, Try-Out, and Transfer of Care. In the Transition to Community phase, services are intended to reinforce community living. In the Try-Out phase, the case manager and peer specialist team begins to reduce service intensity to help the veteran test and readjust the VA and non-VA support systems to fill any gaps. Visits in the Transfer of Care phase are used to fine-tune the connections established with VA and non-VA resources and supports. In CTI, the case manager focuses on supporting veterans in obtaining clinical and entitlement services, while the peer specialist supports veteran engagement in 12-step and other recovery activities.

The second component of MISSIONCJ is DRT, which includes 13 integrated mental health and substance use sessions along with seven EPC sessions delivered by the case manager.52-55 The 13 DRT sessions are highly structured and focus on motivation for recovery54 and relapse prevention,55 and specifically target the co-occurring mental health, substance use and criminal legal issues commonly facing veterans in VTCs. Furthermore, the seven EPC sessions offer veterans strengths-based support around prosocial thinking and behavior that is often intertwined with substance use. While Veterans Justice Program links veterans to substance use, mental health and prosocial thinking and behavior change services, they do not offer them directly, and this project would suggest a substantial expansion of their role. The third component of MISSIONCJ is Peer Support.56,57 Besides the aforementioned CTI offered by peer specialists, they also deliver 11 structured psycho-educational recovery sessions. These sessions are designed to empower veterans to plan for a life of stability, sobriety, and for community integration. While some VJO programs offer unstructured peer support, veterans enrolled in VTCs also receive support from a Volunteer Peer Mentor who works within the court and also offers the veteran linkage support. It is worth noting that the Volunteer Peer Mentors within the court, are also veterans of the armed services, but do not necessarily have lived mental health, substance use or criminal legal experience. With regard to intensity and frequency of MISSIONCJ, each Veteran optimally receives about 2 h of manualized services a week from a case manager and peer specialist team.

MISSIONCJ manuals and trainingMISSIONCJ includes a Treatment Manual,19 which describes the three core components of MISSIONCJ, provides suggestions for service delivery, and includes a number of appendices with additional didactic materials. MISSIONCJ also includes a MISSIONCJ Participant Workbook58 that provides veterans with all of the DRT, EPC and Peer Support session worksheets to review in advance of the treatment sessions or following the sessions to reinforce learning. The workbook also has self-guided readings and other self-help exercises that veterans can use to promote recovery. The MISSIONCJ Participant Workbook is given out by the peer specialist at the onset of MISSIONCJ treatment and is seen as an initial gift as the veterans commence their MISSIONCJ recovery journey.

MISSIONCJ trainingMISSIONCJ case managers and peer specialists will also receive MISSIONCJ educational and training materials (i.e., MISSIONCJ Treatment Manual, Abbreviated Treatment Guides, and Participant Workbook) prior to formal training. They will be asked to review the materials if possible, prior to being offered the formal training. Formal training in this project will be offered via two modalities: 1) MISSION-University (described below), or 2) live virtual training by one of the MISSIONCJ developers that will last two to four hours and covers the MISSIONCJ components. Both the live or MISSION-University training are comparable and VJO staff will be asked to select which they prefer. All staff, regardless of completing MISSION-University or live training also view three recorded training videos on the EPC curriculum.

MISSION-University. Besides the MISSIONCJ Treatment Manual and Participant Workbook, our group developed MISSION-University via funding from the National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA). MISSION-University is an online portal available 24/7 that offers asynchronous leaning that will train staff on the MISSIONCJ components.59 MISSION-University is broken down into five, 1-hour training modules and includes an e-simulation where trainees apply their knowledge to a clinical case. The training provides an overview of the treatment model and covers each of the three therapeutic core components.

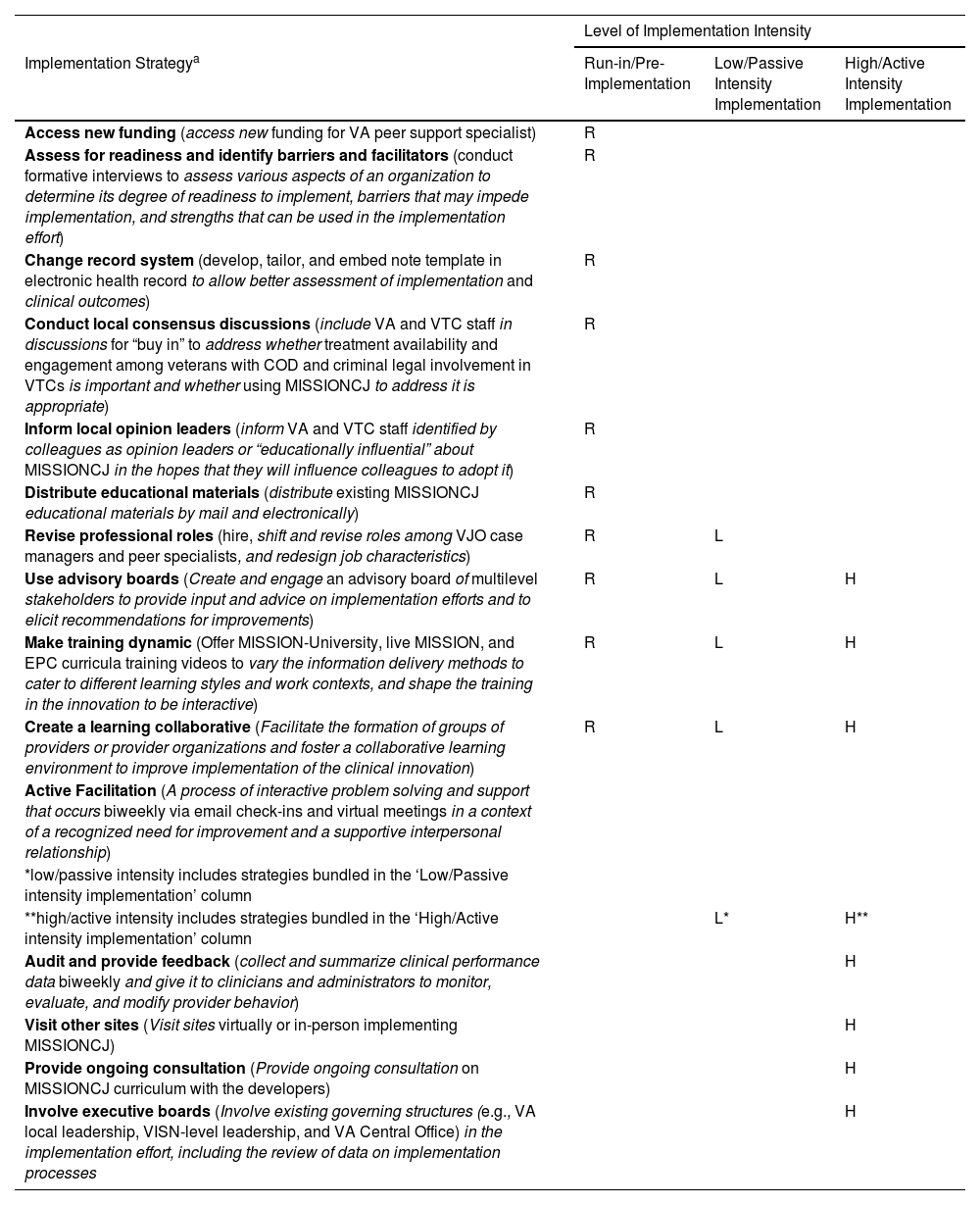

Implementation facilitation strategiesThis QI project will include multiple different implementation facilitation strategies that will be bundled for each level of intensity (i.e., low/passive intensity implementation facilitation and high/active implementation facilitation). Table 2 provides an overview of the implementation facilitation strategies used in the project by level of intensity, including what supports sites received during the run-in/pre-implementation period. Although the majority of implementation facilitation strategies differ for each level of implementation intensity, there are some strategies that will be used across levels of intensity but will be implemented differently (these occurrences are denoted in Table 2 with an asterisk(s), and explanations of how the strategy differs across levels are provided). Implementation facilitation strategies follow the definitions identified by Powell et al., 2015.60

Selected implementation facilitation strategies by level of implementation intensity.

| Level of Implementation Intensity | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Implementation Strategya | Run-in/Pre-Implementation | Low/Passive Intensity Implementation | High/Active Intensity Implementation |

| Access new funding (access new funding for VA peer support specialist) | R | ||

| Assess for readiness and identify barriers and facilitators (conduct formative interviews to assess various aspects of an organization to determine its degree of readiness to implement, barriers that may impede implementation, and strengths that can be used in the implementation effort) | R | ||

| Change record system (develop, tailor, and embed note template in electronic health record to allow better assessment of implementation and clinical outcomes) | R | ||

| Conduct local consensus discussions (include VA and VTC staff in discussions for “buy in” to address whether treatment availability and engagement among veterans with COD and criminal legal involvement in VTCs is important and whether using MISSIONCJ to address it is appropriate) | R | ||

| Inform local opinion leaders (inform VA and VTC staff identified by colleagues as opinion leaders or “educationally influential” about MISSIONCJ in the hopes that they will influence colleagues to adopt it) | R | ||

| Distribute educational materials (distribute existing MISSIONCJ educational materials by mail and electronically) | R | ||

| Revise professional roles (hire, shift and revise roles among VJO case managers and peer specialists, and redesign job characteristics) | R | L | |

| Use advisory boards (Create and engage an advisory board of multilevel stakeholders to provide input and advice on implementation efforts and to elicit recommendations for improvements) | R | L | H |

| Make training dynamic (Offer MISSION-University, live MISSION, and EPC curricula training videos to vary the information delivery methods to cater to different learning styles and work contexts, and shape the training in the innovation to be interactive) | R | L | H |

| Create a learning collaborative (Facilitate the formation of groups of providers or provider organizations and foster a collaborative learning environment to improve implementation of the clinical innovation) | R | L | H |

| Active Facilitation (A process of interactive problem solving and support that occurs biweekly via email check-ins and virtual meetings in a context of a recognized need for improvement and a supportive interpersonal relationship) | |||

| *low/passive intensity includes strategies bundled in the ‘Low/Passive intensity implementation’ column | |||

| **high/active intensity includes strategies bundled in the ‘High/Active intensity implementation’ column | L* | H** | |

| Audit and provide feedback (collect and summarize clinical performance data biweekly and give it to clinicians and administrators to monitor, evaluate, and modify provider behavior) | H | ||

| Visit other sites (Visit sites virtually or in-person implementing MISSIONCJ) | H | ||

| Provide ongoing consultation (Provide ongoing consultation on MISSIONCJ curriculum with the developers) | H | ||

| Involve executive boards (Involve existing governing structures (e.g., VA local leadership, VISN-level leadership, and VA Central Office) in the implementation effort, including the review of data on implementation processes | H | ||

Notes: R = run-in/pre-implementation, L = low/passive implementation, H = high/active implementation; *depicts if strategy changes from low/passive implementation to high/active implementation.

During the initial 9-month run-in/pre-implementation period, VA site interest will be confirmed via a letter of support, and each VA site within the four regions will be engaged either through direct outreach to VA staff, or staff at their affiliated VTCs. No implementation facilitation (i.e., low/passive intensity implementation facilitation and high/active implementation facilitation) will be offered during this phase. Formative interviews will also be conducted to assess site readiness, and to identify contextual barriers and facilitators, guided by the RE-AIM (Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation Maintenance) framework.61

At the end of the run-in/pre-implementation period, each site will then receive the same set of low/passive implementation facilitation strategies for 9 months. Low/passive implementation facilitation includes things such as the formation of a learning collaborative in the form of a community of practice to discuss implementation across sites. During this period, external facilitators (VY, KB) will assist sites and key decision makers through periodic emails and meetings both in one-on-one and group settings to assist with the development of action items, goal setting, and other tasks (e.g., distributing MISSIONCJ materials locally, and installation of an electronic medical record note template to track implementation and fidelity).

At the end of the 9-month period of low/passive implementation facilitation, sites will be assessed to determine if they met the implementation benchmark (15 MISSIONCJ structured curriculum sessions and five unstructured outreach sessions as noted above). Sites that meet this benchmark will be randomized to continue with low/passive implementation facilitation, or to discontinue implementation facilitation for 12 months. Sites that did not meet the implementation benchmark will be randomized to continue to receive low/passive implementation facilitation, or to receive high/active implementation facilitation for 12 months. Those randomized to the latter will receive the same implementation strategies as in the low/passive intensity, plus high/active implementation facilitation which includes such supports such as audit and feedback, with performance discussed with the external facilitator to provide tailored support as well as meetings with leadership to discuss site progress. Sites receiving high/active implementation facilitation will also have consultation calls with the MISSIONCJ developers and each site will have a site visit which will be held virtually or in-person when feasible.

Outcomes and analyses by AIMAim 1a: Identify pre- and post-implementation barriers and facilitators to adopting MISSIONCJTo understand the contexts in which MISSIONCJ will be implemented, we will identify both pre- and post-implementation facilitators and barriers to adopting MISSIONCJ. Data will initially be used to develop fidelity-consistent modifications to MISSIONCJ and to tailor our selected implementation strategies (Table 2) to the local settings.

Data Collection, Participants, and Analysis. We will use a Rapid Assessment, Response Evaluation (RARE)62,63 approach to assessment and program implementation to gather and assimilate formative data from each site to (1) understand the context and resources available for implementation and (2) inform adaptations to MISSIONCJ. We will conduct formative evaluations with key stakeholders at each VA and across VTCs. VJO case managers and peer specialists as well as VTC staff such as judges, probation officers, coordinators, and peer mentors will be interviewed using a semi-structured interview guide based on the Dynamic Sustainability Framework (DSF), which is a framework that examines the ongoing sustainment of practices in the midst of change.64 Interviews will last a maximum of 60 min and be transcribed verbatim. Interviews will be deductively coded using the DSF. Inductive codes will be developed that capture concepts related to the emotions, interactions that are not captured by the DSF.65 Process maps will be created to increase our understanding of practice setting variations. Interviews will be repeated following the completion of the implementation facilitation support as a summative evaluation to understand barriers and facilitators to implementation and sustainability. All interview data will be coded deductively, using the DSF, and inductively. Coding saturation is reached when no new concepts emerge. We will also conduct semi-structured interviews with a sample of key stakeholders (i.e., veteran participants, advisory board members, VA Central Office) to explore RE-AIM elements66 and, when appropriate, perspectives on (including barriers to and facilitators of) educational outreach, implementation facilitation, and needed adaptations to non-core components of MISSIONCJ.67 Coding and analysis of key stakeholder interviews will occur along with coding and analysis of participant data as stated above.

Aim 1b: Conduct an adaptive trial to determine the successful implementation of a tiered/tailored implementation facilitation approach using RE-AIMWe will assess whether intensity of implementation facilitation support as well as adding a tiered/tailored implementation facilitation approach impacts MISSIONCJ implementation in the Hybrid Type III implementation-effectiveness randomized trial using an adaptive design. The evaluation of the trial is guided by RE-AIM.63,66

Implementation Outcomes. Implementation fidelity will be our main implementation outcome designed to capture “successful implementation” and will be identified using a clinical note template including the MISSIONCJ fidelity tool which will be embedded within the VA's electronic medical record and used at all VA sites to document the sessions delivered by the case manager and peer specialist team, and the degree to which MISSIONCJ fidelity is achieved. Specifically, the fidelity tool tracks all the core elements of the MISSION approach, including CTI, DRT, EPC, Peer Support, and linkages to VA and non-VA care. The tool consists of 11 items over the following 6 areas: (1) session details (who, where, when); (2) structured DRT sessions (endorse session number and workbook use); (3) Peer-led structured sessions (endorse session number and workbook use); 4) other relevant treatment/services received; (5) community activities done with client, and (6) referrals/linkages made. We will use General Linear Mixed Models (GLMM) to compare fidelity scores between study conditions. Prior to estimating any models, we will examine the distribution of the outcome and predictor variables. If non-normality in variable distributions is observed for baseline comparisons between clients served in study conditions, we will use data transformation or nonparametric tests of equality between groups. One benefit of GLMM is its capacity to accommodate different conditional distributions for each outcome variable by choosing appropriate link and variance functions within GLMM.68 Models will also adjust for fixed effects based on staff and veteran-level variables (i.e., demographics). For all models, we will employ full maximum likelihood estimation, and, in combination with nested random effects for site staff, we will examine further constraints on covariance structure (e.g., auto-regressive) and choose that which yields the best fit by standard goodness-of-fit indices (e.g., Akaike's Information Criterion).

Implementation outcomes will also be explored using qualitative methods (RARE methods) and through VA administrative data (e.g., electronic medical record data, extracted from the Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW)). RARE methods will be used in Aim 1b as they are in Aim 1a, although in Aim 1b, we will specifically account for whether fidelity, defined as the extent to which an intervention is delivered as intended according to the MISSIONCJ protocol, is upheld.67 During the same interviews as in Aim 1a, we will probe for specific aspects of how MISSIONCJ has been carried out, and these qualitative data will be compared to the clinical notes and the MISSIONCJ fidelity tool, using a framework matrix.

We hypothesize that the RE-AIM framework domains will be improved in sites who continue to receive low/passive implementation facilitation, or who are provided with higher/active intensity implementation facilitation support: (1) Reach: veterans who are approached by VJO case managers or peer specialists to engage in MISSIONCJ (considering demographics, and volume and type of MISSIONCJ received); (2) Effectiveness: see Aim 2; (3) Adoption: staff trained on MISSIONCJ, and staff delivering MISSIONCJ; (4) Implementation: structured (i.e., DRT, EPC, Peer Support) and unstructured sessions completed and fidelity to MISSIONCJ; and (5) Maintenance: continued implementation by VJO case managers and peer specialists, and by sites after discontinuation of implementation facilitation support.

Aim 2: Examine effectiveness outcomesWe hypothesize that for sites that receive ongoing low/passive implementation facilitation or high/active implementation facilitation support, MISSIONCJ will increase linkage to VA and non-VA mental health and substance use disorder care and other behavioral health services. We also hypothesize that under high/active intensity implementation facilitation, MISSIONCJ will reduce days of substance use and reduce criminal recidivism. Using veterans as the unit of analysis, we will employ a mixed-effect modeling approach to assess the impact of adding implementation facilitation to educational outreach on MISSIONCJ implementation and effectiveness outcomes. In these models, the key term of interest will be a month by implementation strategy interaction term, which will capture impact of implementation strategy on rate of change of outcomes of interest. Information on the effectiveness of implementation facilitation (and the strategies involved in this) on veterans’ treatment and health outcomes, will be captured in an implementation playbook that will be distributed throughout VA at the conclusion of the trial.

Data Collection. We will rely on administrative data from the VA CDW which captures inpatient and outpatient service utilization. Additionally, a service utilization tracking sheet will be collected on a quarterly basis to track referrals and linkages to non-VA services during the project period. These utilization data (i.e., CDW for VA tracking, and service utilization form for non-VA tracking) will be combined to estimate the direct effect of each project condition (i.e., effect of high/active implementation facilitation, low/passive implementation facilitation, and discontinuation) on health outcomes including: (1) inpatient hospitalizations; and (2) engagement in substance use disorder/mental health disorder treatment; (3) CDW status notes on substance use; and (4) CDW status notes on criminal legal involvement.

Status and timelineThis QI project commenced in October of 2021 and is scheduled to be completed in September of 2025.

DiscussionAs noted above, research evidence and passive implementation facilitation strategies often do not change clinical practice or increase the adoption of new practices. MISSIONCJ has demonstrated evidence in specialty courts, including VTCs, yet it has not been widely adopted in VA. This project intends to test whether VA sites that receive ongoing low/passive implementation facilitation, or who are provided with higher intensity support aid in MISSIONCJ's implementation in VTCs, and secondarily to evaluate the effectiveness of MISSIONCJ on veteran treatment outcomes. If successful, ongoing low or higher intensity implementation facilitation could be used as a model to support MISSIONCJ implementation or the implementation of other multicomponent evidence-based intervention more widely in complex settings. The project findings should be available by 2025.

Ethical considerationsThis effort (QUE 20–017) is approved as a quality improvement project by the VA Bedford Healthcare System Institutional Review Board, the U.S. form of a research ethics committee.