This study examined problematic video game use and its sociodemographic and clinical correlates in a sample of 1,410 Spanish video game players (33.6% women; mean age = 21.12 years, SD = 3.29).

MethodsThe participants completed a comprehensive set of assessment scales to evaluate clinical features: a sociodemographic interview, problematic video gaming (using the GAS-7), emotional symptoms (with the Goldberg Anxiety and Depression scales), suicidal ideation (with the Paykel Suicidal Ideation Scale), loneliness (De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale) and impulsivity (UPPS-P scale). Participants were classified based on problematic gaming severity. Differences between groups were explored for the clinical features assessed.

ResultsAs a result, most participants showed a low-risk gaming pattern (88.2%), in comparison to those showing either excessive use of video games (10% of participants) or problematic (pathological) gaming use (almost 2%). Risk groups differed by sex (p < .01), but not age, education, or employment. Game time and frequency varied across risk groups, indicating higher use with greater risk. Clinical correlates were examined, with higher risk groups showing more depressive symptoms (p < .01), anxiety symptoms (p < .01), suicidal ideation (p < .01), and loneliness (p < .01). Impulsiveness dimensions also showed significant group differences, except for sensation seeking. In conclusion, problematic video game use was linked to higher levels of depressive symptoms, anxiety, suicidal ideation, loneliness, and impulsiveness.

ConclusionThis study sheds light on the clinical aspects associated with different levels of problematic gaming.

Problematic video game use is recognized as a clinically relevant problem and is included in international diagnostic and disease classification manuals. The DSM-5 introduced "Internet gaming disorder" (IGD) in section 3, recognizing its distinctive clinical features but noting the need for further research for taxonomic consideration and highlighting this category diagnostic as being subject to investigation. It was defined as persistent and recurrent use of Internet gaming that causes distress or impairment over at least 12 months.1 In addition, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially incorporated Gaming Disorder (GID) as a mental health disorder in the 11th revision of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11).2

Previous studies have reported that the prevalence of problematic video game use varies across countries.3,4 A recent meta-analysis with 227,665 participants from 29 countries revealed that the overall prevalence of Gaming Disorder (GD) was 3.3% (8.5% in males and 3.5% in females), with a range from 0.3% to 17.7%.5

In Spain, previous studies also showed inconsistent results, with prevalence rates ranging from 3.3% to 7.1% in adolescents.6,7 A recent study with a representative sample (N = 41,507) reported prevalence data and identified risk and protective factors associated with these risky behaviors. Specific scales were used to measure problematic Internet use and online gaming addiction based on the DSM-5 and ICD-11 criteria. The results showed a prevalence of 3.1% for problematic gaming using the DSM-5 approach.8 However, a more conservative approach based on the ICD-11 showed 1.8%. Additionally, risk and protective factors were identified, including gender, parental education, internet connection time, and mobile phone use in class.

A study by Fuster et al.9 is one of the few to provide data on young adults, where a prevalence of 2.6% was reported. Studies are needed concerning Spanish young adults that address video game-related problems and video game addiction using reliable inter-country instruments, thereby minimizing cultural effects in determining the actual prevalence.10,11 The frequency of video game use among the general population varies from daily use to sporadic or use only in a social context. Relevant factors including the device (computer, console, mobile device, others), age, and sex can explain this fluctuation. Among Spanish adults, Alonso-Díaz et al.12 found that over 26.7% of men and 17.2% of women played video games daily. Further data should be provided in terms of other relevant sociodemographic factors such as education attainment or the frequency of video game use.

Clinical correlates, such as depressive symptoms, anxious symptoms, motivations for playing, and quality of life dimensions, are found to be related to the severity of problematic video game use. Lower levels of personality organization are associated with greater problematic gaming, and this relationship is mediated by depressive symptoms and socializing and achievement motivations.13 In addition, a higher severity of problematic gaming is associated with lower health-related quality of life in all dimensions, particularly in physical well-being and school environment.14,15 These findings suggest that various clinical factors and dimensions of quality of life play a role in the severity of problematic video game use.

Clinical correlates of problematic video game usePrevious studies have reported consistently that problematic video gaming was associated with various mental health problems such as depression and anxiety16,17; as well as with unhealthy lifestyle habits (sedentary lifestyle and drug use).18 Excessive video gaming has also been associated with an increase in suicidal ideation among adolescents and young adults.19 In contrast, certain studies have failed to ascertain a substantial relationship between these variables and problematic video game usage20 or have discovered that engaging in video games reduces stress, anxiety, and depressive symptoms, even during the pandemic.21,22 A recent systematic review encompassing 24 studies examined the impacts of video games during the initial phases of the COVID-19 crisis on stress, anxiety, depression, loneliness, and gaming disorder. It revealed that video games, particularly augmented reality and online multiplayer formats, alleviated stress, anxiety, depression, and loneliness among adolescents and young adults facing stay-at-home measures. However, concerning individuals at risk, notably male youths, engaging in video games exhibited adverse effects.23 Therefore, the empirical evidence is presented in a contradictory manner, underscoring the need for further research to elucidate this relationship.

On the other hand, previous investigations have established consistently a strong correlation between loneliness and addiction to gaming.24,25 Additionally, it is essential to recognize that loneliness not only serves as a cause but can also be a consequence, suggesting a potential bidirectional relationship.15 Other research has indicated that while there are short-term benefits, excessive gaming does little to foster the establishment or sustenance of real-world connections. Instead, the substitution of real-life interpersonal interactions with gaming could potentially exacerbate the deterioration of existing social relationships, thus intensifying feelings of loneliness.26 Consequently, we anticipate a positive relationship between problematic video games and loneliness.

Furthermore, high impulsivity has also been emphasized in previous studies involving samples of video game players.27,28 However, a distinct contrast has been revealed in a study between problem gamblers and problematic video game players.29 For instance, Choi et al.30 discovered notable variations, wherein individuals with DSM-5 Internet Gaming Disorder exhibited markedly higher impulsivity; those with gambling disorder displayed heightened compulsivity. Although problematic video game use has been associated with high impulsivity, impulsivity across multiple domains has not been investigated thoroughly in this population. In this context, the UPPS-P model, derived from existing literature and refined over time, postulates five impulsivity factors: (lack of) perseverance, (lack of) premeditation, positive and negative urgency, and sensation-seeking.31 Notably, empirical studies have shown that higher levels of lack of perseverance, as well as positive and negative urgency, are distinguishing features between patients with problematic gaming.32,33 Similarly, the absence of premeditation is correlated positively with suboptimal decision-making.34 A recent study discovered elevated levels of all assessed dimensions of impulsive tendencies in the (diagnosed) problematic video game players group versus the control group.33

Despite social concerns, playing video games is considered in general to be a common leisure activity, with only a small percentage of players experiencing health problems derived from problematic use. However, global figures on screen time exposure and video game use in the post-pandemic times are rarely optimistic in terms of problematic video gaming prospects.35,36 This shows a need to develop appropriate instruments to measure problematic video gaming, which can then be used to study physical and mental burdens derived from problematic video gaming on a community basis, across countries.

Expanding on the previous information, we have formulated the research question: How does the problematic video gaming among Spanish young adults affect the emotional symptoms (anxiety and depression), loneliness, suicidal ideation, and impulsive behavior? Our general objective is to explore the relationship between the problematic video game use and different psychological variables of interest in a sample of young Spanish adults. The main goal of this research is to provide substantial empirical evidence on the issue of problematic video game use among young Spanish adults. We utilized an instrument facilitating cross-cultural comparisons to enhance existing knowledge and gain deeper insights into excessive video game use in Spain. Additionally, we aimed to uncover clinical factors contributing to problematic video gaming. Our specific objective was t:o1 analyze the relationship between problematic video game addiction and emotional symptoms (anxiety and depression), loneliness, suicidal ideation, and impulsive behavior.

MethodParticipantsThe population sample consisted of 1410 Spanish young adults. The participants were between the ages of 18 and 34 (M = 21.12; SD = 3.29) of which 936 (66.4%) were men and 474 (33.6%) were women. All these participants were video gamers. Most of participants (n = 1041; 73.8%) had a university education. In terms of employment, 68.7% of the participants indicated that they were only studying (n = 968), 12.3% (n = 173) were only working, and 15.8% (n = 233) indicated they were both working and studying. Finally, and to a lesser extent, 1.8% (n = 25) indicated that they were unemployed and 1.5% (n = 21) responded that they were in another situation.

Participants should fulfil the following inclusion criteria: a) aged between 18 and 35 years old at the time of answering the questionnaire; b) Being a video game player; c) Have Spanish nationality; d) Consent to voluntary participation, having been informed of the implications of their participation in the study.

InstrumentsSociodemographic data and the use of games: Various information was collected regarding sociodemographic characteristics (i.e. gender, age, employment status, educational level) and gaming patterns (frequency of use, amount of time).

Problematic game use: The Game Addiction Scale - GAS-737 is a brief, self-administered scale that assesses video game-related problems. The Spanish adaptation was carried out by Irles et al.38 establishing a type of individual and collective application of a total of 7 items. We used the GAS-7 version by de la Torre-Luque et al.39 in which a conceptual adaptation was conducted to better adjust to Spanish language usage. The items present a graded response format with five options (1 = Never; 2 = Rarely; 3 = Sometimes; 4 = Often; and 5 = Very often). “In the last 6 months" is used as a time specifier. This version of the GAS-7 fitted well to a unifactor structure on a sample of young adults (N = 522), χ221 = 919.22, RMSEA = 0.08, robust CFI = 0.95. The reliability of the scale was also adequate, with Cronbach's α = 0.81.

Depression and Anxiety: The Goldberg Anxiety and Depression scale40 contains 2 subscales with nine questions in each: the anxiety subscale (questions 1- 9) and the depression subscale (questions 10 −18). The last 5 questions of each scale are only asked if there are positive answers to the first 4 questions. The response format for each item is binary (0 = No; 1 = Yes). Higher scores indicate greater severity of symptoms. The reliability of the scale was adequate, McDonald's ω = 0.88 for the total scale and with Cronbach's α = 0.8 in the anxiety subscale and Cronbach's α = 0.78 in the depression subscale.

Ideation suicide: The Paykel Suicidal Ideation Scale41 consists of a total of five items with a dichotomous response system (0 = No; 1 = Yes). At a theoretical level, higher scores indicate greater severity. The time frame refers to the last year. The reliability of the scale was adequate, with Cronbach's α = 0.8.

Loneliness: The De Jong Gierveld Loneliness Scale42 consists of 11 items with three response categories (1 = No; 2 = More or less; 3 = Yes). The items refer to whether people experience situations where the number of interpersonal relationships is lower than desired or whether the desired level of intimacy has been reached. The loneliness score is obtained by dichotomising the responses so that 1 point is obtained if More or less or No is answered for items 1, 4, 7, 8 and 11. For the remaining items, 1 point is awarded if the answer is More or less or Yes. The final score ranges from 0 (No loneliness) to 11 (Extreme loneliness), which is the sum of the number of affirmative and negative responses for all items. The reliability of the scale was adequate, with Cronbach's α = 0.82.

Impulsiveness: The full version of the Impulsive Behavior Scale- UPPS-P43 is composed of 59 items, with 10–14 items per scale. This scale aims to assess impulsivity from a multidimensional perspective. For this study we used the short version that assesses five different dimensions of impulsivity: positive urgency (items 3, 10, 17, 20), negative urgency (items 6, 8, 13, 15), sensation seeking (items 9, 14, 16, 18), lack of premeditation (items 2, 5, 12, 19) and lack of perseverance (items 1, 4, 7, 11). Items are scored on a 4-point Likert-type scale (1 = Strongly Agree; 2 = Somewhat Agree; 3 = Somewhat Disagree; 4 = Strongly Disagree). Higher values translate into higher levels of impulsivity. The items of each scale are averaged together. The reliability of the scale was adequate, with McDonald's ω = 0.88 for the total scale.

ProcedureA cross-sectional study was conducted and the participants were selected by convenience sampling. All subjects gave their informed consent for inclusion before they participated in the study. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and the protocol was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Universidad Complutense de Madrid (protocol code C.I. 20/089-E was approved on March 11, 2020). The survey web link was disseminated through the webpages of the institution and on the official social media sites Twitter and Facebook. The survey was available from april 2020 to april 2022. No financial assistance or compensation was offered to participants.

Data analysisTo address the objective, three groups of problematic video game use were established using the GAS-7 instrument: a) low-risk group of problematic use (i.e., participants with a normalized use of video games); b) excessive use group (i.e., participants who excessive use group (i.e., participants who responded with 'sometimes' or higher frequency on four to six of the GAS-7 items); c) pathological use group (i.e., participants who responded with 'sometimes' or higher frequency on all of the GAS-7 items).

Due to the unbalanced sample size of the different groups, non-parametric tests were carried out in which a similar sample size in all groups was not required. In addition, the effect size (eta squared) was obtained to analyse the sensitivity of the results.

First, descriptive statistics were computed (average and standard deviation for quantitative variables and proportion of cases for nominal and ordinal variables) to present the characteristics of the 3 groups of problematic use of games in terms of sociodemographic and clinical variables. Subsequently, contrast tests were performed. In this regard, differences by risk groups for problematic video game use were studied, using Pearson's χ2 (Chi-square) test or the Fisher-Freeman-Halton exact test, as appropriate, for the categorical variables and the Kruskall-Wallis test for variables of a quantitative nature, due to the results obtained after studying the normality distribution for each dependent variable (symptoms of depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, loneliness, and impulsivity) using Kolmogorov-Smirnoff and Shapiro-Wilk, which indicated that there was not normality in the dependent variables. The p-value was set to 0.05.

In the case of Kruskall-Wallis test, differences by pairs of groups were tested by applying the post hoc Mann-Whitney test. The data were analyzed using IBM-SPSS 28.

ResultsThe sample comprised 1410 video game players (33.6% women). Mean age was 21.12 years old (SD = 3.29). Most participants were university students (71%). Over a quarter of sample (23.9%) played video games on a daily basis. A higher proportion of participants (45.1%) reported playing video games several days a week. Mean time playing video games was 2.18 h (SD = 1.27).

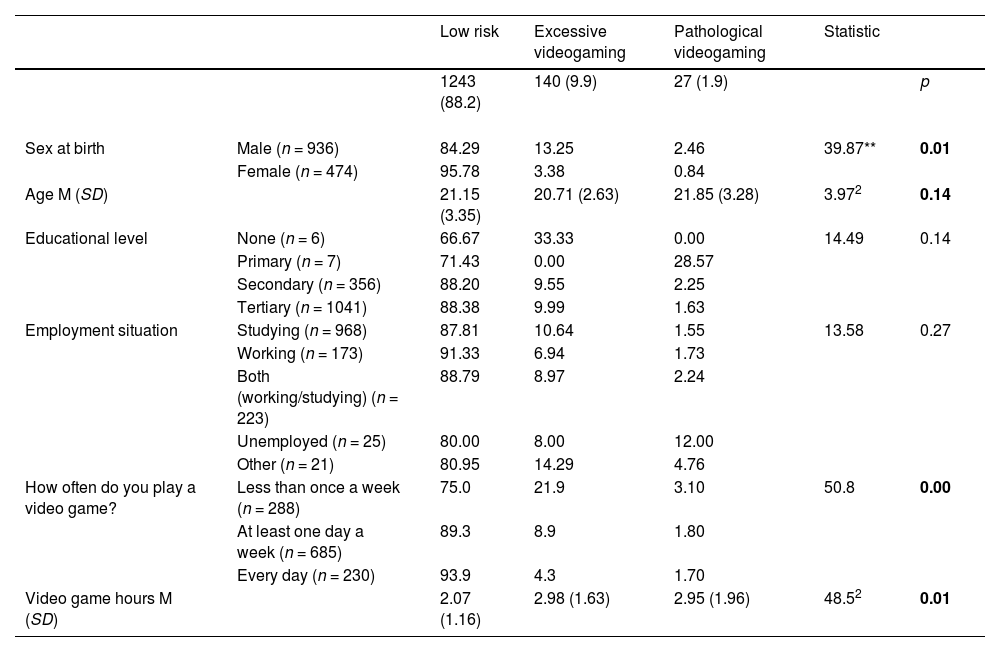

We classified our participants following the classification algorithm provided by Lemmens et al.37 This allows to rank the severity of problematic video gaming. As a result, we found that most participants were not at risk (or present a low risk) of problematic video gaming (n = 1243, 88.2% of sample); the polythetic risk of problematic videogaming (also labelled as excessive use) was found in almost 10% of sample (n = 140). Almost 2% (n = 27) showed GAS-7 scores surpassing the clinical point of monothetic problematic video gaming (so-called, pathological use). The Tables 1 and 2 displays descriptive data on the sociodemographic and clinical features of our sample, according to their risk level of problematic video gaming. Differences were found between the risk groups by sex, χ22 = 39.87, p < .01. A higher proportion of women was observed in the low-risk group. The three groups did not differ significantly in terms of age, education level and employment situation (p > .05; see Table 1).

Characteristics of the participants by problematic game use groups.

| Low risk | Excessive videogaming | Pathological videogaming | Statistic | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1243 (88.2) | 140 (9.9) | 27 (1.9) | p | |||

| Sex at birth | Male (n = 936) | 84.29 | 13.25 | 2.46 | 39.87** | 0.01 |

| Female (n = 474) | 95.78 | 3.38 | 0.84 | |||

| Age M (SD) | 21.15 (3.35) | 20.71 (2.63) | 21.85 (3.28) | 3.972 | 0.14 | |

| Educational level | None (n = 6) | 66.67 | 33.33 | 0.00 | 14.49 | 0.14 |

| Primary (n = 7) | 71.43 | 0.00 | 28.57 | |||

| Secondary (n = 356) | 88.20 | 9.55 | 2.25 | |||

| Tertiary (n = 1041) | 88.38 | 9.99 | 1.63 | |||

| Employment situation | Studying (n = 968) | 87.81 | 10.64 | 1.55 | 13.58 | 0.27 |

| Working (n = 173) | 91.33 | 6.94 | 1.73 | |||

| Both (working/studying) (n = 223) | 88.79 | 8.97 | 2.24 | |||

| Unemployed (n = 25) | 80.00 | 8.00 | 12.00 | |||

| Other (n = 21) | 80.95 | 14.29 | 4.76 | |||

| How often do you play a video game? | Less than once a week (n = 288) | 75.0 | 21.9 | 3.10 | 50.8 | 0.00 |

| At least one day a week (n = 685) | 89.3 | 8.9 | 1.80 | |||

| Every day (n = 230) | 93.9 | 4.3 | 1.70 | |||

| Video game hours M (SD) | 2.07 (1.16) | 2.98 (1.63) | 2.95 (1.96) | 48.52 | 0.01 |

Relationship between clinicals characteristics and problematic game use groups.

| Low risk | Excessive videogaming | Pathological videogaming | Statistic | Effect size | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | HK-W (df) | ή2 | |

| Depression (n = 1297) | 2.95 (2.38) | 3.88 (2.50) | 5.22 (2.70) | 30.6962,⁎⁎ | 0.03 |

| Anxiety (n = 1297) | 4.48 (2.70) | 4.72 (2.62) | 6.73 (2.33) | 15.0172,⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Suicide ideation (n = 1335) | 0.83 (1.35) | 1.30 (1.50) | 1.96 (1.67) | 30.9692,⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Loneliness (n = 1337) | 3.24 (3.07) | 4.28 (3.48) | 7.73 (3.03) | 20.1752,⁎⁎ | 0.02 |

| Impulsiveness | |||||

| Lack of premeditation (n = 1296) | 7.26 (2.29) | 8.09 (2.55) | 7.73 (3.02) | 12.0552,* | 0.01 |

| Lack of perseverance (n = 1301) | 8.28 (1.44) | 8.76 (1.61) | 8.83 (1.59) | 14.4772,⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Negative urgency (n = 1307) | 8.89 (2.89) | 9.87 (2.84) | 10.30 (3.21) | 18.362,⁎⁎ | 0.01 |

| Positive urgency (n = 1029) | 9.77 (2.44) | 10.45 (2.27) | 10.39 (2.62) | 8.352,* | 0.01 |

| Sensation seeking (n = 1303) | 9.90 (3.01) | 10.01 (2.98) | 9.59 (3.40) | 0.3882 | 0.00 |

Note.

Regarding game time (hours), a statistically significant difference was observed (p < .01) among the groups. It was observed that the low-risk group had a mean game time of two hours (M = 2.07; SD = 1.16), followed by the pathological risk group (M = 2.95; SD = 1.96), and finally the excessive risk group with the highest usage time (M = 2.98; SD = 1.63). Post hoc tests indicated the presence of differences among the three study groups, demonstrating that game time is differently related to various levels of risk associated with video game use. While more hours of gameplay are associated with lower low-risk (p < .001), they are also linked to a higher risk of excessive use (p < .001). However, no clear relationship is observed between game time and pathological risk in the studied sample (p = .987). Regarding the frequency of gaming, significant differences were found among the groups (p < .01). Out of the total players, n = 685 reported playing at least once a week. Among them, the majority were classified in the low-risk group (89.3%), followed by the excessive gaming group with 8.9%, and only 1.80% were in the pathological gaming group. Among the n = 288 participants who reported playing less than once a week, 75% were categorized as low risk, 21.9% as excessive gaming, and finally, 3.1% belonged to the pathological gaming group. Lastly, n = 230 participants reported playing every day, of whom 93.9% were placed in the low-risk group, 4.3% in the excessive gaming group, and a smaller percentage.

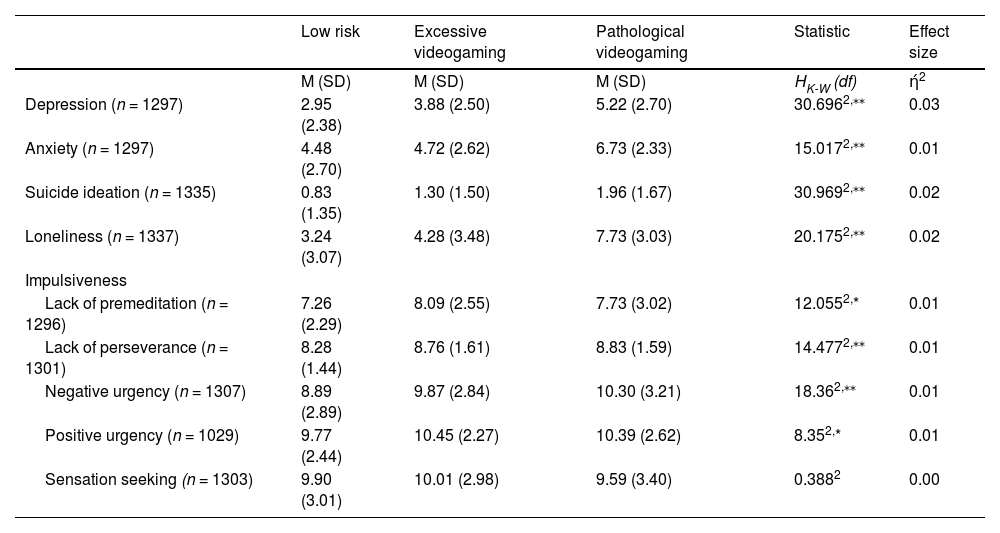

Regarding the clinical correlates of problematic video game use (see Table 2), participants exhibiting depressive symptoms (n = 1297) demonstrated significant differences among the three groups, as shown by the Kruskall-Wallis test (p < .01). Post hoc tests indicated the presence of differences between the three study groups (p < .05). The "pathological video game use" group displayed a higher mean of depressive symptoms (M = 5.22; SD = 2.7), followed by the "excessive use" group (M = 3.88; SD = 2.5), and finally, the low-risk group (M = 2.95; SD = 2.38). It should be noted that the depression symptoms and problematic gaming has a meaningful effect size (ή2 = 0.03), implying a moderate association.

Similarly, participants showing symptoms of anxiety (n = 1297) exhibited differences between groups according to the Kruskall-Wallis analysis (p < 0.01). Post hoc tests indicated the presence of differences between the pathological videogaming and both low risk and excessive videogaming study groups (p < .01), but not between the low risk and excessive videogaming groups (p = 0.328). Specifically, the "pathological video game use" group had a higher mean of anxiety symptoms (M = 6.73; SD = 2.33) compared to the "excessive game use" group (M = 4.72; SD = 2.62), and to a lesser extent, the low-risk group (M = 4.48; SD = 2.7).

Regarding suicidal ideation (n = 1335), the Kruskall-Wallis analysis showed significant differences between groups (p < .01). Post hoc tests indicated the presence of differences between the low risk and both excessive and pathological videogaming (p < 0.01), but not between the excessive and pathological videogaming study groups (p = .06). Specifically, the "pathological video game use" group had a higher mean of suicidal ideation (M = 1.96; SD = 1.67), followed by the "excessive video game use" group (M = 1.30; SD = 1.51), and to a lesser extent, the low-risk group (M = 0.83; SD = 1.35). The suicidal ideation shows a moderate association with problematic gaming (ή2 = 0.02).

Furthermore, regarding the feeling of loneliness (n = 1337), the Kruskall-Wallis test revealed a significant difference among the three groups (p < .01). Post hoc tests indicated the presence of differences between the low risk and both excessive and pathological videogaming (p < 0.01 and p < 0.05), but not between the excessive and pathological videogaming study groups (p = 0.1). The "pathological video game use" group exhibited a higher mean (M = 7.73; SD = 3.03) compared to the "excessive use" group (M = 4.28; SD = 3.48) and the low-risk group (M = 3.24; SD = 3.07).

Four dimensions related to impulsive behavior showed significant differences among the groups according to the Kruskall-Wallis test (positive urgency, negative urgency, lack of premeditation, lack of perseverance) (see Table 2). However, the dimension of Sensation seeking did not display any differences between the groups (p = .82).

In particular, the dimension of Lack of premeditation (n = 1296), post hoc tests indicated the presence of differences only between the low risk and excessive videogaming study groups (p < .01). Specifically, the group exhibiting excessive gaming had a higher mean (M = 8.09; SD = 2.55) compared to the group classified as pathological gaming (M = 7.73; SD = 3.02), and to a lesser extent, the low-risk group (M = 7.26; SD = 2.29). Conversely, in the dimension of Lack of perseverance (n = 1301) the presence of differences was only significant between low risk and excessive videogaming groups (p < 0.01), the group with pathological gaming had the highest mean (M = 8.83; SD = 1.59), followed by the excessive gaming group (M = 8.76; SD = 1.61), and the low-risk group (M = 8.28; SD = 1.44), respectively.

On the other hand, in the dimension of Negative urgency (n = 1307), according to the post hoc test, the means were significantly different between low risk and excessive and pathological gaming groups (p<.05). The mean was higher in participants classified as pathological gamblers (M = 10.30; SD = 3.21), followed by the "excessive gaming" group (M = 9.87; SD = 2.84), and finally the group with low-risk gamers (M = 8.89; SD =2.89).

Similarly, in the dimension of Positive urgency (n = 1029), according to the post hoc test, there were differences between the low risk and the excessive gaming groups (p<.01) with the excessive gaming group obtaining the highest mean (M = 10.45; SD = 2.27) compared to the other two groups.

Regarding the sensitivity of the study, the effect sizes found indicate mild to moderate associations between the variables and the different groups of problematic video game use (ή2 = 0.01 – 0.03). Thus, these significant results indicate sample differences due to the large sample size, which prevents inflation of the type I error.44

DiscussionThe present study addressed the problem of video game use among young adults in Spain, focusing on sociodemographic factors and clinical correlates. In this sense, it is important to emphasize that this is the first descriptive study in the Spanish population in this age range, as well as the first to address clinical correlates associated with the use of video games. Additionally, while Bernaldo-de-Quirós et al.45 have examined factors associated with the problematic use of video games in adolescents and young people in Spain, their study does not present disaggregated data for young adults specifically. Our study, therefore, provides a unique and necessary contribution to understanding video game use and its clinical implications within this specific demographic.

The results revealed a variable presence of problematic use within our sample, with 10% for the excessive use group and 1.9% for the group designated as pathological use, according to the classification of Lemmens et al.37 These findings are consistent with previous investigations that have identified similar prevalence ranges both nationally6-8 and internationally.3–4,20 However, it should be noted that there is variability in the instruments and methodology employed among the aforementioned studies.

In terms of game characteristics, it is observed that more than 20% of the sample plays video games on a daily basis, while approximately 45% play several days a week. It is interesting to note that the distribution of gaming frequency in this study largely coincides with trends identified by other researchers.37 In particular, the study by Alonso-Díaz et al.12 found that more than 26.7% of men and 17.2% of women played video games on a daily basis. Accordingly, the current findings support the idea that the use of video games is a common leisure activity in these stages.

Along the same lines, the relationship between frequency of gaming and risk of problematic use, the findings of this study suggest that time spent gaming could be associated with levels of risk. It is observed that those who play more hours per week present a higher proportion of problematic use, although this seems to be more pronounced in the excessive use group compared to the pathological use group. These results could indicate that more time spent gaming could contribute to the development of a pattern of problematic gaming, although not necessarily at pathological levels.

Regarding sociodemographic characteristics, differences were obtained only between gender and frequency of gaming, which is consistent with previous literature. Numerous studies highlight gender-based disparities in problematic video game usage, indicating that males generally exhibit higher levels of engagement than females.12,46 Specifically, one study uncovered that 30% of males were identified as playing at problematic levels, whereas only 7.4% of females fell into this category.47 Another study further illustrated that males engage in more frequent and online gaming compared to their female counterparts. These variations may be attributed to various factors, including personal preferences, cultural and social roles, as well as the themes and typology of video games. However, it is crucial to note that these specific variables were not analyzed in the present study. Additionally, no significant associations were observed among the three groups concerning age, education level, and employment situation, potentially attributable to the homogeneity of the population.

Therefore, while our study highlights the importance of considering the time spent playing video games, it is crucial to recognize that playing time was not significantly associated with the severity of problem gambling. Playtime alone may not be inherently problematic, and future research should further explore the combination of factors that may influence the development of pathological video game use in this specific population.

The objective of this research was to examine the relationship between problematic video game addiction and levels of emotional symptoms (anxiety and depression), loneliness and suicidal ideation, as well as impulsive behavior. Our findings reaffirm the high percentage of young adults with clinical symptomatology related to problematic video game use.17,22–23 These results are relevant, given that youth and early adulthood is a crucial stage in the development of a person's life, full of challenges and learning. Facing important social, occupational and personal challenges characterize this stage of life.48 As a consequence, this stage is particularly sensitive to the development of internalizing symptomatology (anxiety and depression) and other related factors (suicidal ideation, loneliness and/or impulsivity).7 Not much is known about the relationship of these factors with the problematic use of video games in this age group, which may become an important moderating element.

Specifically, the scientific literature highlights an important relationship between depressive symptoms and video game problematic; in particular, such users may be affected by depression.16 In this study, a high relationship was observed between the GAS and depression. A possible explanation could be that video game playing is associated with a release of dopamine that is similar in magnitude to drugs of abuse.49 Thus, addicted players may use video games in an uncontrolled manner to obtain pleasure, thereby relieving symptoms of depression. However, these behaviors maintain a cycle that prevents patients from resolving both their addiction and depression. It would be interesting to investigate this aspect in future research. Similarly, it is crucial to delve into the complex connections among problematic smartphone use, sleep quality, bedtime procrastination, and video game addiction in young adults individuals. While existing studies have uncovered the negative impact of problematic smartphone use on sleep latency50 and its bidirectional relationship with depressive symptoms51 there is a notable gap in research addressing the interplay between bedtime procrastination, video game addiction, and sleep quality. Further investigation is essential to grasp the interactions among these factors and their collective influence on the sleep quality of young adults individuals.

Anxiety was likewise evident among the cohorts exhibiting problematic video game usage in this study. This result is in line with what has been found by previous studies.15,22 Frequently, individuals with anxiety disorders employ games as a means of seeking solace (a type of evasion). This approach enables individuals to sidestep in-person interactions and substantially amplifies virtual relationships. Although the potential for video game addiction to arise as a result of anxiety disorder development exists, a longitudinal investigation revealed that participants who ceased pathological gaming tendencies exhibited reduced instances of depression, anxiety, and social phobias in comparison to those who persisted in such behaviors.52 Future research should explore the connection between resilience and video gaming, given resilience's pivotal role in personal well-being. Resilience exhibits a negative correlation with mental health issues like depression and anxiety, while positively correlating with factors like life satisfaction and positive affect. This is confirmed by a recent systematic review and meta-analysis.53

Our findings reaffirm the high percentage of young adults with suicidal ideation among the problematic video game use group, suggesting a possible risk of psychological impairment in this population. These findings are consistent with previous research on the relationship between suicidality and problematic video game use.19,54 For example, a recent systematic review, which included 12 cross-sectional studies, with a total of 88,732 participants, showed that 11 of the 12 included studies found positive associations between problematic gaming and suicidal ideation and attempts.19

Based on previous literature, it is hypothesized that the relationship between problem gambling and suicidal tendencies could be mediated by various causal mechanisms and pathways. On the one hand, it is postulated that gambling addiction could increase the propensity for suicidal tendencies due to increased psychological distress and impulsivity.27,55,56 Furthermore, it is considered that individuals with gaming problems might spend more time on this activity, thus exposing themselves to elements that potentially increase suicidal behavior, such as cyberbullying and violence in video games.57,58 However, it is crucial to note that the relationship between violent games and real-world violence is a controversial issue.59 It is also suggested that people with suicidal ideation might turn to video games as a means of escape.60

In this context, another relevant finding points out that problematic video game use is associated with feelings of loneliness in this population. This is consistent with previous research indicating that video game addiction tends to increase social isolation and feelings of loneliness.20,25,26 In fact, individuals tend to favour online interactions over offline interactions that could foster social relationship building.61

Loneliness is an important risk factor in the development of suicidal ideation or suicide attempts.62 Thomas Joiner's (2005) Interpersonal Theory of Suicide highlights the lack of a sense of belonging as a major risk factor in the formation of suicidal ideation. In this theory, lack of belongingness and the perception of being a burden to others are two factors that contribute to active suicidal ideation.63,64 We suggest that these cognitive moderators for suicide may be linked with the feelings of loneliness, even though a direct relationship between these variables cannot be established. Longitudinal studies are recommended to confirm these hypotheses, controlling for the relevant variables and elucidating their mechanisms and causal relationships.

Overall, nearly all the UPPS-P dimensions, namely negative and positive urgency, lack of premeditation, and lack of perseverance, exhibited significant associations with problematic video game use. These findings are consistent with previous research linking these dimensions of impulsivity to problematic video game use30,32 while the sensation-seeking dimension showed no significant relationship with problematic usage. In this regard, a study conducted by Michalczuk et al.65 indicated that urgency dimensions (i.e., negative and positive urgency) were strongly linked to gambling behaviors. Furthermore, differences were observed between problematic gambling participants and controls across all other impulsivity dimensions, except for sensation seeking. This distinction might be associated with the specific nature of video games and their potential to evoke intense emotions without necessitating a strong inclination for seeking new experiences.

The urgency subscales comprise positive urgency and negative urgency. The former denotes a tendency to engage in impulsive actions in response to extremely positive emotions. Consequently, impulsivity is correlated with positive emotions and immediate positive reinforcement.43 Negative urgency refers to impulsive behaviors triggered by experiencing negative emotions. In this scenario, impulsivity is linked to negative emotions and negative reinforcement, involving avoidance behavior or relief-seeking.

It is worth noting that the lack of premeditation exhibited the highest mean among the most problematic groups in video game usage. A prior study by Billieux et al. ,32 involving a clinical sample, described how individuals with gambling problems exhibited higher levels of urgency and lack of premeditation when compared to control individuals.

Future research should explore different facets of impulsivity across various contexts and in relation to individual disparities in gambling-related cognitions to gain a more precise understanding of how different aspects of impulsivity interrelate with gambling behaviors.

It should be noted that current studies indicate that Problematic video gaming can be explained by a combination of cognitive, social, and health-related factors. Cognitive factors associated with problematic gaming include cognitive deficits such as impaired executive functioning and hazardous decision-making, as well as cognitive biases like attentional biases and cognitive distortions.66 Social factors, such as engagement in the game and problem awareness, also play a role in problematic gaming. Additionally, mental health factors like general mental health, gender, and age can contribute to problematic gaming, although to a lesser extent.67 Health-related factors, such as withdrawal symptoms, mood modification, and conflict, have been identified as factors related to problematic mobile video gaming.67 These findings highlight the importance of considering cognitive, social, and health-related factors when addressing problematic gaming behaviors and developing preventative and therapeutic programs.

It should be noted that this study has limitations that should be considered. One of these is that the cross-sectional design only allows us to account for the magnitude of the association between the variables, so it is not possible to assume causal relationships. Additionally, the lack of objective measures (e.g., electroencephalographic data while playing) and ecological measures (derived, for instance, from ecological momentary assessment protocols) may be another shortcoming to provide more accurate relationships with clinical outcomes, as data were collected through self-reported measures. The lack of diversity in the sample, predominantly comprising young adult university students, may limit the generalizability of results to broader populations. To enhance comprehensiveness and representativeness, future research should incorporate participants from various demographic groups, including those not engaged in university education.

As a non-random sample, it is imperative to consider and discuss the limitations and potential biases introduced by the selection method. Participation bias in studies on mental health problems and problematic behaviors may skew results toward individuals already concerned with these issues, impacting generalizability. Factors such as loneliness and impulsivity may manifest differently in evolving cultural contexts; therefore, the study suggests that future research should include additional variables like social network and relationship quality for a richer understanding of youth's social experiences related to video game use and its effects on mental health.

Another limitation is the absence of control variables such as emotional dysregulation, personality, socioeconomic status, pre-existing mental health conditions, or other relevant factors that might influence the studied variables. Lastly, the study does not contextualize the data collection within the COVID-19 period, although the study's protocol and objectives were formulated prior to the pandemic. Future research should address these limitations for a more comprehensive interpretation of results and a better contextualization of findings within the participants' social environment.

Furthermore, the data collection period covering the COVID-19 lockdown in Spain may have significantly impacted the results. The lack of analysis on the homogeneity of the sample collected during and after the lockdown means we cannot determine if the sample is proportionally distributed between these periods or if any period is overrepresented. Future research should address these limitations for a more comprehensive interpretation of results and a better contextualization of findings within the participants' social environment.

ConclusionThis study provides an approach to the current situation of problematic video game use among young adults in Spain. The prevalence of problematic use found in the sample is around 10%, suggesting the need to implement preventive measures and intervention programs aimed at this population. The findings also emphasize the importance of considering the emotional and social aspects related to excessive video game use, such as anxiety, depression, suicidal ideation, impulsivity and loneliness. Furthermore, the results support the need for gaining deeper insight into the features of video gamers to better understand pathways towards adaptive and maladaptive coping.

Given that research on problematic video game use remains an evolving field, further exploration is needed to understand underlying causes, cultural dynamics, and effective interventions. Future studies could further explore the relationship between problematic video game use and other risk factors, as well as explore specific interventions to reduce the negative impact of this behavior on the mental health of this population.

FundingThis work was supported by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III-FIS under grant number PI20/00229 and cofunded by European Regional Development Fund (ERDF), ‘A way of making Europe’. Institutional Review Board Statement: The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of Universidad Complutense de Madrid (protocol code C.I. 20/089-E was approved on March 11, 2020) for studies involving humans.

Informed consent statementInformed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.