This article presents a structured review of the literature about corporate social responsibility, from the origins and evolution of the discipline, as a field of research, until the present. A review is also presented on the main contributions of authors and institutions in relation to the promotion of social responsibility, focusing on two complementary trends that have gained prominence as theoretical support: institutional theory and stakeholder approach. Some controversies and discussions generated in the years around the concept are also discussed.

The increasing complexity and turbulence of the environment provokes that firms should develop competitive management models aimed not only at obtaining profit margins in the short term, but also to meet the balanced expectations of society and the different stakeholders involved in its activities in the long-term (Crane, Mcwilliams, Matten, Moon, & Siegel, 2008; Solano, Casado, & Ureba, 2015).

Regarding these requirements for companies, corporate social responsibility (CSR)1 has been proclaimed in recent years as a key tool that helps companies to meet these environmental pressures as well as to improve its competitiveness as a result (Aguilera, Rupp, Williams, & Ganapathi, 2007; Boulouta & Pitelis, 2014; Carroll & Shabana, 2010). The analysis of the concept CSR reveals that for a long period of time, organizations have played a fundamental and exclusive economic function in society, contributing actively in the distribution of goods and services, and the generation of wealth and employment.

However, in recent decades, circumstances such as: (i) the growing number of corporate fiscal abuses and opportunistic strategies in the financial landscape (Sami, Odemilin, & Bampton, 2010); (ii) the increase of social inequalities reflected in the poverty, hunger or discrimination among countries (De Neve, 2009); (iii) the great power held by multinationals (Bouquet & Deutsch, 2008); or (iv) the environmental degradation accused by the planet (Lindgreen, Maon, Reast, & Yani-De-Soriano, 2012), have generated that the parties affected by firm's decisions and outcomes – shareholders, employees, unions, customers, suppliers, citizens, local community, government, etc. – the requirement of a greater commitment and responsibility from organizational activities.

Given these requirements, in accordance with the fundamentals of institutional theory (Dacin, Kostova, & Roth, 2008) and stakeholder perspective (1984), which argue that companies must gain the support of society and the various stakeholders to operate with greater freedom and guarantees of survival, companies are progressively adapting their behaviour and actions, guiding them to a greater commitment to these parts.

Considering the previous frame, this article concentrates its efforts on providing an analysis of the literature on corporate social responsibility, focusing on two main theories (institutional and stakeholder), which have helped to develop, consolidate and internalize this concept and management philosophy as a necessary and crucial for organizational success. The manuscript also examines some controversy around the term corporate social responsibility and its implications for businesses today, thus providing future research lines.

Literature review: origins and foundations, moving towards a change in responsible business modelResearch in social responsibility reveals that a large number of scholars have been reflecting on the raison d’etre of a company, and whether it should pursue a dual economic and social function (Friedman, 1970; Galbreath, 2010; Lozano, 1999).

Specifically, the origin of the debate on corporate social responsibility goes back to the early twentieth century, where the intensity where the intensity of increased production merges with the second phase of the Industrial Revolution highlighting Western Europe, United States of America and Japan. In this process, the consolidation of capitalism as an economic philosophy, the first proposals for a welfare state and/or labour shortages reflect some social and labour shortages in the management system (Araque-Padilla & Montero-Simó, 2006).

The situation experienced in this period led authors such as Weber (1922) and Clark (1939) to express the need to educate businesspeople towards a new framework of social responsibility. In these efforts, leading business schools, with Harvard as a reference point, and professional magazines like Fortune have joined in a common purpose: to demonstrate that executives and managers of companies, might achieve a competitive management model through responsible guidance of their actions from an economic point of view (i.e., ensuring the payment of wages for employees, suppliers responsibilities in contracts, reduction of risk for shareholders, etc.). Moreover, it is necessary from a social point of view to identify improvement aims for the common good of the community in which firms operate.

Based on these initial contributions, the first work arose in the fifties, formally defining the concept of social responsibility as ‘the set of moral and personal obligations that the employer must follow, considering the exercise of policies, decisions or courses of action in terms of objectives and values desired by society’ (Bowen, 1953: 6).

With this argument Bowen, generally called the father of the term social responsibility, pointed out that companies can have a significant influence on the lives of citizens, and consequently firms should intervene in improving and solving their main economical and social imbalances. Therefore, in addition to considering the economic function, organizations should contemplate the social consequences resulting from their actions. From this work, the concept of social responsibility starts to take on increased interest as a research topic as Carroll (1999) postulates, a work which examines in detail the evolution of the concept, subdividing the decade into different key periods that have helped the progressive institutionalization of this mental attitude of responsibility between business and academia.

Among these works, it is necessary to highlight the ideas of Drucker (1954) who discusses the need to take the factor of public opinion into account in the decision making process of any organization, regardless of size or industry. According to the author, this idea is based on the experiences of multinationals such as Ford and General Motors, which in the mid-50s received much criticism from the press, media and various national regulatory institutions, due to the development of behaviours qualified as ‘irresponsible’, which had not considered the interest of their communities. These companies had to take further action to regain the trust of these customers (creating channels of communication, collaborating with environmental organizations, implementing a social volunteer programme for employees, etc.). With these arguments Drucker reflects that even major companies are subjected to an environment of wide social pressure, which consequently determine their actions in the market in the long term.

Regarding these ideas, in the early sixties, Davis (1960) contributed to the concept of social responsibility, suggesting that, depending on the number of agents affected by organizational actions, they must look after their interests in order to win their endorsement and support. Therefore, Davis advised that organizations that use their power without worrying about causing impact on the environment might lose the respect and trust of their stakeholders (customers, suppliers, employees, shareholders, etc.), qualities that Davis considers determinants for success and business consolidation. This idea will be developed in literature through the trend termed ‘corporate constitutionalism’, which contemplates the firm as a social institution that must exercise its power responsibly, with their groups’ interest at heart, in order not to be punished and expelled from the market (Davis, 1960).

Since the mid-sixties, Davis (1967) frames the studies of social responsibility as a macro organizational issue that goes beyond internal and technicians’ interest of any company. So far, the works published highlight how the assumption of greater responsibility on the part of the companies could improve their results in relation to particular interest groups. However, Davis’ proposals suggest the need for organizational activities to be developed in line with the institutional context that surrounds and affects businesses, it being necessary to know what other companies (competitors or firms which belong in the same sector) and institutions require in economic and social terms. This process, according to Davis, is what helps companies to redefine their responsibilities and commitments regarding their agents, who make up their community.

Taking into account the previous contributions, Walton (1967) stressed that social responsibility emerges as a set of actions that managers try to implement for companies to improve their relationship with the broad range of interest groups that make up their environment. In addition, Walton (1967) made a decisive contribution to the understanding of what social responsibility is, and how it can be activated among organizations. In this regard, Walton highlights that the essential ingredient of social responsibility is the degree of voluntariness by business, because such action is not mandatory, and the decision to carry it out involves the assumption of a significant cost and risk, which can affect the success or failure of a business in a decisive way. Therefore, considering the imbalances and the investment required to develop social responsibility actions, authors like Wallich and Mcgowan (1970) added that, with regard to the viability of social responsibility action, which may ensure a company's success, and to conduct their activities without restrictions, they must maintain a balance between the economic and social interests of their stakeholders.

The contributions examined in the fifties, sixties and early seventies help academics to understand the role that social responsibility plays in the adjustment process of the company, with the environment and with stakeholders.

In the eighties, as Carroll (1999), Garriga and Melé (2004) and Lee (2008) reflect, there is a great theoretical dispersion that aims at analyzing the benefits and advantages of implementing actions in terms of social responsibility by firms.

After considering this large body of approaches, this study, unlike the study of Carroll (1999), is focused on the analysis of social responsibility from two disciplines that, although separated, have evolved in parallel, and can provide a better explanation of the need to internalize socially responsible behaviour by firms in response to environmental pressures: the institutional theory (Fernández-Allés, 2001; Meyer & Rowan, 1991; Scott, 2007); and the stakeholder theory (Freeman, 1984; Freeman, Harrison, Wicks, Parmar, & De Colle, 2010).

Contributions from institutional theory to the implementation of socially responsible behavioursFor decades organizational strategies and actions have been adapted to requirements and environmental pressures (Fernández-Allés & Valle-Cabrera, 2006). Following this argument, the response to the context in which companies operate and keep their actions and behaviours consistent with principles demanded by external and internal context is considered vital for organizational survival (Dacin, 1997; Fuenfschilling & Truffer, 2014).

This internalization process of a set of norms, beliefs, values and principles accepted by society and the community allow organizations to achieve the support and backing of their activity, which is known as legitimacy (Cruz-Suárez, Prado-Román, & Díez-Martín, 2014; Suchman, 1995). Among the advantages of the legitimation process, organizations could achieve more efficient access to resources from certain stakeholders – investor funds, support from government, increased sales and customer loyalty, access to the negotiation of contracts with different suppliers and distributors, obtaining the respect and commitment of employees, etc., as a process that helps to improve the organization's economic and financial performance (Brammer, Jackson, & Matten, 2012).

Internally, institutionalization and internalization of norms, values and social behaviours and structures arises from formal and informal processes, which take place between internal groups within the company (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991). Moreover, the external environment is considered essential with regard to the possibility of establishing a set of relationships between the company and Government laws and regulations, professional associations (licensing and certification) and other organizations, especially those that are within the same sector (Fernández-Allés, 2001).

Regarding this, DiMaggio and Powell (1983) point out that companies will adapt more efficiently to their environment and can achieve legitimacy and the benefits they derive from it if they: (i) Consider the legal and political pressure exerted externally by agencies such as the Government – coercive isomorphism – due to the fact that there is a creator and regulatory power enhancer and promoter of change rules, which inspects and punishes accordingly; (ii) Mimic the processes, practices and strategies of the most successful companies – mimetic isomorphism. In this process it could be argued that cognitive power, i.e. a set of beliefs, assumptions and explicit knowledge, codified and specialized, is a framework through which to perform organizational routines that help internalize these best practices; and finally; (iii) Collaborate with professionals, taking into account the experience and previous training of managerial personnel to generate a professional knowledge that will address the problems of the environment for firms with greater confidence – normative isomorphism (Fernández-Allés, 2001).

Although the result of the mechanisms of isomorphism implies that organizations are very similar, empirical evidence shows that those using these processes can improve their position in the market, getting their business to be perceived as desired by public institutions and the wide range of their community stakeholders (Schultz & Wehmeier, 2010).

These contributions, framed within the approach of old institutionalism, help to explain why organizations view the imitation of behaviours identified in their environment as able to ensure the legitimacy of the groups and institutions that shape it. However, the new institutional trend, conceived as neo-institutionalism, suggests that organizations and their strategies are substantially influenced by cultural factors, legal, historical and political institutions that define specific patterns of behaviour for different regions or countries (Doh & Guay, 2006; Powell & DiMaggio, 2012).

Support of this neo-institutional basis might explain what influence these factors have on the socially responsible actions undertaken by companies. Significant within this institutional contemporary framework is the theoretical support of Keim (2003), who identifies several institutions that should be considered in the analysis of the context:

(i) Formal institutions, which are constitutions, laws, policies and formal agreements created and validated by citizens from different localities and countries; (ii) informal institutions, which rule behaviour and mental models and are generated by individuals via cultural heritage, religious beliefs or policies. These rules, in the field of business, are coded as informal practices and routines. In addition, there are some key institutions for national and supranational political, legal and social legislation, from which jurisdiction specific to a particular territory or geographic area emanates. Following this classification, to examine the implementation of socially responsible behaviours among companies, the institutional environment is interpreted in contexts such as Europe and North America, traditionally marked by different historical and political factors, which affect the particular way in which respective companies make decisions about social responsibility.

Focusing the analysis on European territory, due to Spain being the country in which the research is framed, it should be mentioned that there has been a high turnover of policies at the community level by different Member States, determining the generation of a large number of legislations to harmonize laws and regulations. For example: the Maastricht Treaty, 1993; Amsterdam Treaty, 1996; Treaty of Nice, 2000 (Doh, 1999; Doh & Guay, 2006). The integration of these countries under a monetary system and common government influence can affect the reformulation of traditional relationships between businesses and Governments, aimed in this case at achieving a coherent system of welfare in these European countries (Doh, 1999). Concretely, bodies such as the European Commission, the Parliament and the Spanish Council of Ministries are positioned as expert advisors on negotiation and improvement of these collective European interests.

In terms of CSR at the European level, the elaboration and publication of the Green Book of CSR by the European Commission (2001) is highlighted as one of the prime manuscripts to promote a common framework in which responsible behaviour for entrepreneurs and managers may be developed within the European Union. Despite the importance of these European figures in the formulation of policies and procedures which promote social responsibility, according to Doh and Teegen (2002) and Doh and Guay (2006), reflect that NGOs and the general public have been two of the main promoters at institutional level to have driven the imperative to develop socially responsible behaviours in firms during recent decades. More specifically, negative ecological impacts such as discharges of toxic air pollution by companies, or socially negative impacts such as gender inequalities or the use of child labour have led to several platforms being built and to NGOs expressing their dissatisfaction, expressing the need for more regulation of these aspects. With these arguments there is a progressive institutionalization and concern by companies to develop responsible behaviour, leading to numerous studies that have attempted to demonstrate the relevance and added value of including social responsibility as a part of organizational goals (Branco & Rodrigues, 2006).

Other factors such as the financial position in the market, the level of enterprise competitiveness, or a history of political baggage in some countries, encourage firms to position themselves as complementary constraints in the course of implementing socially responsible behaviour (Campbell, 2007; Sementelli, 2005).

In response to the ideas, and the need to respond to the demands of the institutional environment, there is a significant body of work that proclaims itself as essential to social responsibility, in its ability to respond to the large number of players involved in activity that influences business performance (Freeman, 1984; Greenwood & Anderson, 2009; Ley & Wood, 2014). This framework represents the main support of stakeholder theory.

Contributions from stakeholders theoryThe development of the stakeholder perspective implies the transformation of the traditional bilateral relationship established between the firm and only some of the relevant groups, such as shareholder or owners, into alternative multilateral relationships, which include the employees, unions, customers, suppliers, the Government, investors, media, competitors or the local community (Argandoña, 1998; Bridoux & Stoelhorst, 2014).

The origin of the stakeholder concept arises from the field of business management, introduced by Freeman and defined as ‘any group or individual who can affect or be affected by the decisions and the achievement of corporate objectives’ (Freeman, 1984: 25). Given the multitude of parties involved in organizational activities, such as those stated by Freeman (1984), Goodpaster (1991) and Clarkson (1995) it is necessary to differentiate between and prioritize them according to a single criterion in order to meet their expectations with a logical order. These previous works use a double distinction of stakeholders by way of consensus regarding their nature and the relationship established with the organization: (i) a primary group, which usually has a formal contract with the firm and is essential for its proper functioning (owners, shareholders, employees, unions, customers, suppliers, etc.) and (ii) a secondary group which, despite not being directly involved in the economic activities of the company and not having a contractual relationship with it, can exercise a significant influence on its activity (citizens, competitors, local community, the Government, public, etc.).

The influence, power and claims that each of these parts have on the company has been analyzed in works such as Mitchell, Agle, and Wood (1997). In this regard, a solid and broad theoretical framework has been built related to the stakeholders theory, that shows how satisfying the interests of these parties can help companies to improve their financial performance and subsequently their competitiveness and sustainability (Harrison, Bosse, & Phillips, 2010). Specifically, Goodpaster (1991), Donaldson and Preston (1995) and Fassin (2009) argue that there are different forms of analysing and studying the management of interest by companies. Thus, Goodpaster (1991) appreciates three theoretical trends that explain the behaviour of firms in relation to their stakeholders. Firstly, the strategic approach, which argues that stakeholders can facilitate or hinder the achievement of the organizational aims. Secondly, the responsibility approach, which explains how establishing a quality relationship with those groups of interest, can provide more benefits for companies through achieving their satisfaction. Thirdly, the convergent approach which stands as an intermediate trend from both previous approaches.

Additionally, Donaldson and Preston (1995) propose another three trends to examine and analyze stakeholders management with accuracy: (i) the descriptive approach, which aims to explain that companies are defined by a broad set of different interests that must be balanced, a process that can induce better or worse results; (ii) the instrumental approach, which explains how the stakeholder management of the company is an instrument or a tool to meet specific, traditional organizational goals: profitability, stability and growth and (iii) the normative approach, supported by the fact that the management and satisfaction of stakeholder interests should be the main goal to be achieved by the company, leaving economic benefits in second place.

In connection with the implementation of CSR actions according to Mitchell et al. (1997), stakeholder theory shows that the behaviour of the company will be influenced not only by agents with great power and dependence on the organization (shareholders, employees, investors, etc.), but also by other outside groups such as social and environmental activists, professional critics, the media, the press, etc.

For example, Henriques and Sadorsky (1999) found that the perception of interests and environmental demands of particular interest groups did significantly influence the level of environmental commitment adopted by companies in their practices. For these reasons, Phillips, Freeman, and Wicks (2003) proposed to adapt and modernize stakeholder's theory into a version able to capture and simplify these groups into five internal categories: financial control agents (e.g. shareholders), customers, suppliers, employees and communities in which the company operates (including competitors). Phillips also proposes six specific external groups: the Government, environmental organizations, NGOs, professional critics or experts, the media and others in general (citizens, local or those which affect or will be affected by companies). The reason why these groups may have an influence on the company, although they do not control essential resources, is explained by the legitimacy concept (Lee, 2011). In the words of Scott (2007: 45) legitimacy ‘is not a commodity to be possessed or exchanged by companies, but rather a condition that reflects the cultural alignment, normative support, or consonance with the rules or laws of the environment’. This idea leads us to uncover a natural and complementary theoretical link between institutional theory and stakeholder approach, given the influence that interest groups could have on the implementation of socially responsible behaviour required of the companies by society.

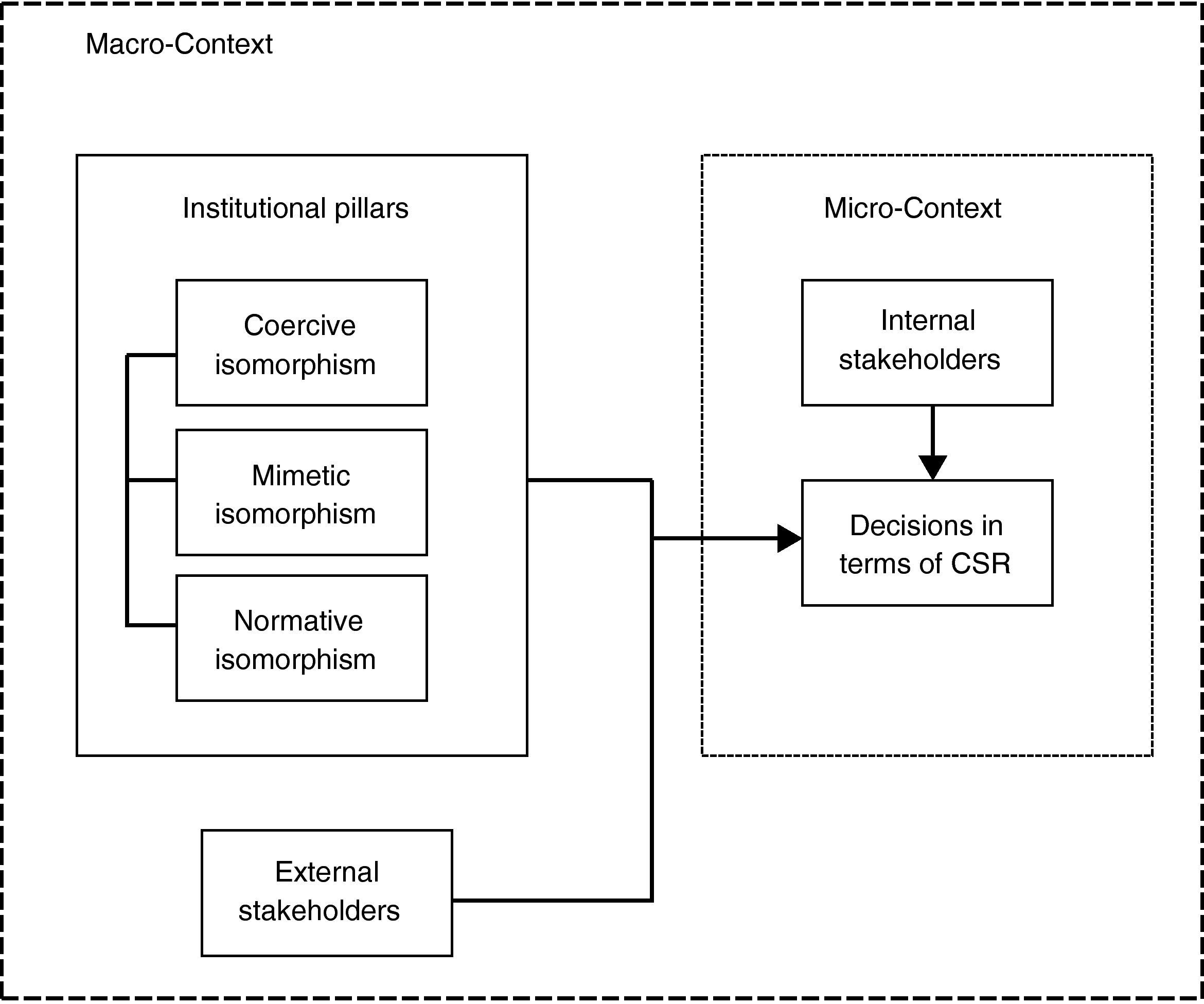

On the basis of theoretical arguments presented, we can conclude that both the institutional theory and stakeholders approach represent two solid pillars to explain and analyze the incorporation of corporate social responsibility actions by firms (Fernando & Lawrence, 2014; Marano & Kostova, 2015; Verbeke & Tung, 2013) as Fig. 1 illustrates.

In this way, the institutional pillars proposed by DiMaggio and Powell (1983), reflect how the pressure on companies may condition their decisions in terms of social responsibility actions. According to Clarkson (1995), it will be necessary to distinguish and consider the influence they can further exert upon external groups affected by or affecting business activity interest. These mechanisms composing the external macro-context of the company are of great importance for companies’ attention, something that will determine their survival in the market. Internally, the micro-context would consist of those domestic interest groups with links to the company, able to exercise power over decisions on social responsibility as expressed in Fig. 1.

The next section provides a structured review of the main contributions that have helped with the practical institutionalization among companies of socially responsible behaviour, facilitating its understanding and importance in the process of analyzing and responding to the pressures exerted by the environment and stakeholders of the company.

Institutionalization of corporate social responsibilitySince the seventies, international organizations such as the Committee for Economic Development (CED, 1971) have attempted to demonstrate the importance that social responsibility as a management model can exercise on growth and sustainability of companies in society. To achieve this process, CED proposes three key functions that companies must undertake to behave responsibly according to their role in society: (i) an internal function of an economic nature aimed at the distribution of products and services that will generate jobs and inject income into the community; (ii) an intermediate function that meets the expectations, values and social priorities of the stakeholders and (iii) an external function, which tries to reduce social and environmental imbalances in society. The characterization of these three commitments by the CED banishes simplified concepts of social responsibility that are defined only as isolated philanthropic actions or donations made by companies to legitimize their activities. Additionally, the CED proclaims that social responsibility must become a tool that helps companies to express their willingness to be part of the social and economic system in which they exist.

In the late eighties and early nineties, an international institution known as the World Commission on Environment and Development (WCED) ratified in the Brundtland Report (1987), and later at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro (1992) two important elements. On the one hand, the importance of studies by academics from the early seventies on sustainable and responsible behaviour undertaken by companies and, on the other hand, the relevance of meeting the needs and aspirations of the present without compromising the resources and capabilities available in the future.

The contributions of the WCED underlies that the economic growth of companies must be underpinned by developing solutions to eliminate the main common problems that impact daily on society, like environmental contamination (pollution, non-renewable energy, lack of recycling, etc.) and social inequalities (poverty, hunger, underdevelopment within countries, etc.) in order to preserve its sustainability and responsible development. These contributions underline the need for companies to minimize their economic, social, and environmental ‘triple impact’ on society, in order to preserve a sustainable and balanced development within it.

In the late nineties and early twenty-first century it will be the World Business Council for Sustainable and Development (WBCSD) which is positioned as a global partnership dedicated to exploring sustainable development alternatives for companies, sharing knowledge, experiences and efficient practices. The power and impact of this partnership lies in its cooperation with governments, NGOs and intergovernmental organizations, running and financing the business projects of energy efficiency and corporate sustainability. According to the WBCSD (1999) CSR can be understood as a commitment of business to contribute to sustainable economic development, working with employees, their families, the local community and society at large to improve the quality of life of their groups. This definition has placed more emphasis on the need to pursue the balanced and sustainable development of enterprises, highlighting specifically facets like the defining of employees and their families as a decisive interest group as well as the community in which enterprises operate.

Other international initiatives that have helped to promote the importance of integrating social responsibility in business management are: the Principles of Global Compact promoted by the United Nations Global Compact (2000); the OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises (2000); the CSR Green Book prepared by the Commission of the European Communities (2001), and the Tripartite Declaration of the International Labour Organization concerning Multinational Enterprises and Social Policy (2002). Concretely, within a European framework, the contribution of the Green Book on CSR is decisive, as prepared by the Commission of the European Communities (2001: 3), which aims to promote corporate social responsibility at European and international level through the development of innovative practices, increased transparency and assessment tools to validate social responsibility among firms.

In this respect the Green Book of CSR understands social responsibility as the voluntary integration by companies of social and environmental concerns in their business operations and their relationships with their partners. Additionally, according to the fundamentals of the Green Book, being ‘socially responsible’ does not mean only compliance with legal and statutory obligations, but also with those social duties which represent constant investment in human capital or the community in which the company participates. Therefore, this European initiative highlights the altruistic value of social responsibility actions, and its progressive support at European level.

As a consequence of the gradual increase of definitions of CSR, not only by academics but also by institutions, Van Marrewijk (2003) emphasizes the multidisciplinary breadth and scope of CSR as well as a certain solid base of these contributions based on the support of institutional and stakeholder theories.

Therefore, Van Marrewijk (2003) understands CSR as a tailored process in which each organization should select specific sustainability goals to adapt to the changes and challenges of the environment. Similarly, McWilliams, Siegel, and Wright (2006) argue that corporate social responsibility acts as an enabler for companies involved, according to their characteristics and objectives, social and environmental actions as well as other emerging demands of society, the industry and community. The above statements highlight how the size or organizational structure of a company may affect the definition of CSR objectives.

In an attempt to extract commonalities and consensus in the literature regarding a definition of CSR, the bibliometric analysis conducted by Dahlsrud (2008) highlights that all of the definitions set up until this year have three points in common: (i) the importance given to the stakeholders; (ii) the voluntary degree of CSR actions by companies and (iii) the reference to these actions representing a set of social, economic and environmental obligations, and the association of these commitments with sustainable development. According to Dahlsrud after analyzing 37 definitions of CSR, there is no description arising out of optimum performance derivative actions on social responsibility, and how those can affect the decision making of the company. Additionally, the analysis of Dahlsrud shows that issues such as globalization, the new dynamic and competitive context in which business operates, the new actors and international laws are changing the expectations that society places on businesses and altering the way of citizens’ lives. From the work of Van Marrewijk and Dahlsrud it can be extracted that the term CSR has evolved in parallel with the environment and the expectations of society in business. Taking into consideration the conclusions of the previous authors, and in line with the stakeholders and institutional approaches, this research promotes as a most suitable the definition of CSR by the European Commission (2011) which understood CSR as the process of integration in the organizational activities of social, environmental, ethical and human concerns from their interest groups, with two objectives: (1) to maximize value creation for these parts, and (2) to identify, prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of organizational actions on the environment. The conceptualization of the European Commission highlights the importance of stakeholders, the need to create value for them as well as to respond to environmental or institutional pressures, trying to prevent the consequences of organizational actions.

After this review of the concept CSR, we can state that there is no consensus on the definition of social responsibility. Additionally, a coherent and consistent pattern is appreciable in the conceptual proposal regarding CSR in the literature, describing a phenomenon increasingly latent in society, although there are still no tools or guidance on how to manage its effects. Indeed, there remains a distinct need for continuing to analyze the impacts of CSR on organizational performance.

Conclusions, discussion and future linesThe review and analysis of the literature reveals the importance of carrying out socially responsible behaviour as a strategy of legitimation and survival for companies, basing this process on the basis of two main approaches such as institutional theory and the stakeholder approach. So far, many studies have reported the separate importance of these theoretical approaches where the relevance of socially responsible actions are concerned. Nevertheless, these works do not conclude that these approaches can act as complementary and may provide a significant degree of explanation of why companies adopt social responsibility practices, and the value derived from these actions for the stakeholders. Using this double theoretical approach, it can be argued that response to pressures and economic, social, ethical and environmental requirements of different stakeholders of the company that make up its environment, help to increase organizational competitiveness.

However, despite the evidence and theoretical advances, there is a high heterogeneity and inconsistencies regarding the measurement of actions and results derived from an empirical point of view. In the meta-analysis made by authors such as Allouche and Laroche (2005), Moneva and Ortas (2010) and Orlitzky, Schmidt, and Rynnes (2003) a number of limitations can be extracted that represent opportunities for future contributions in the field of corporate social responsibility at theoretical and empirical terms:

- (i)

The lack of a single theoretical framework, which contributes to the theoretical dispersion phenomenon, is difficult to study and further research can begin prior contrasted with a support;

- (ii)

The use of a wide variety of population (sizes, sectors, countries), which avoid the generation of inferences in statistical terms;

- (iii)

Methodological shortcomings in measuring the impact of social responsibility actions on financial performance. Considering that CSR represents an intangible construct or latent variables of great complexity in its measurement, it is very difficult to find practical tools to provide an efficient support by researchers to compare the results of these actions on the profitability and performance of the company;

- (iv)

The need to analyze the longitudinal basis of the relationship between social responsibility activities and performance indicators. The reason is that these social actions, until they are perceived and treated as actions that create value for stakeholders, requires a ripening period, which necessitates measuring this reaction in a large temporary space, which can be about two or three years.

Regarding the limitations exposed, it is necessary to continue exploring the external and internal effects of CSR actions in tangible variables (economic and financial results), and intangible variables (innovation, intellectual capital, organizational reputation). Within these intangible effects, it will be extremely relevant to examine how corporate social responsibility can generate shared value. According to Porter and Kramer (2011), the term-shared value involves creating economic value in a way that also creates value for society by addressing its needs and challenges. Considering the approaches reviewed in the current article, the concept of shared value is implicitly related to the essence of institutional perspectives and stakeholders, trying to provide a value in response to the needs and requirements of society and stakeholders. This value must go beyond the actual economic value, trying to create social and environmental value, helping companies to set goals that can ensure sustainability and an adequate future for all its citizens.

According to the European Commission, CSR is defined as “the process of integration in the organizational activities the social, environmental, ethical and human concerns from its groups of interest with two aims: (1) to maximize the value creation for these parts, and (2) to identify, prevent and mitigate the adverse effects of firm actions on the environment” (European Commission, 2011: 6).