The competences of intensive care (ICU) nurses in their healthcare environment, have increased with the acquisition of new responsibilities associated with new care and devices for critical patients. Many studies suggest the need for specific training of nurses that work in these units. Based on this evidence, the European Federation of Critical Care Nurses Associations (EfCCNa), recommends unifying the training of intensive care nurses. Therefore we set ourselves the following objective: to assess the training needs detected by ICU nurses through their experience and practical knowledge.

MethodDescriptive qualitative study, with a phenomenological approach, through semi-structured interview where the four areas (clinical practice, professional, management and educational) covered by the EfCCNa were studied. Fifteen nurses from an adult polyvalent ICU were interviewed

ResultsThe interviewees acknowledged that the previous training was deficient for the care and support measures that they had to face. They considered that subsequent training and experience were decisive in order to carry out their work effectively. They also stated that support measures and care are topics to be developed continuously through targeted training.

ConclusionThe nurses in this research study acknowledged that training is needed to achieve the competences required in ICU, and these are affected by the type of unit and patients.

Las competencias que abordan en su entorno laboral las enfermeras de cuidados intensivos (UCI), han aumentado con la adquisición de nuevas responsabilidades asociadas a cuidados y dispositivos a realizar al paciente crítico. Múltiples estudios avalan la necesidad de la especialización de las enfermeras que trabajan en este tipo de unidades. Apoyado en estas evidencias, la European Federation of Critical Care Nurse (EfCCNa), recomienda unificar la formación de las enfermeras de cuidados intensivos. Por tanto, nos planteamos el siguiente objetivo: valorar las necesidades formativas que detectan las enfermeras de UCI a través de sus vivencias y experiencias profesionales.

Material y métodoestudio cualitativo descriptivo, con enfoque fenomenológico, a través de una entrevista semiestructurada donde se estudiaron los 4 ámbitos que la EfCCNa recoge (clínico, profesional, gestión y educativo). Se entrevistaron a 15 enfermeras de una UCI polivalente

ResultadosLos entrevistados reconocen que la formación previa era deficiente para los cuidados y medidas de soporte que tuvieron que afrontar. Consideran que la formación posterior y la experiencia fueron determinantes para poder desarrollar efectivamente su labor profesional. Además afirman que las medidas de soporte y los cuidados son temas a desarrollar continuamente mediante una formación dirigida.

ConclusiónLas enfermeras reconocen que debe existir una formación destinada a cumplir las competencias que las UCIs requieren, y que estas se ven afectadas por el tipo de unidad y el tipo de pacientes atendidos.

What do we know/what does this paper contribute?

Nurses work professionally in intensive care with no requirements prior to choosing these departments. The conditions of the users themselves, their critical status and vulnerability in addition to clinical support needs require professionals to deal with great variability of care in a short space of time. This has led the scientific societies themselves to attempt to homogenise nursing competences, but no support has been received from the institutions.

What are the implications of the study?

The nurses themselves acknowledged in the research study that specific training measures must be adopted in the units themselves because they feel that the knowledge and skills they had when they graduated from university were insufficient for them as novices. And even though they are already veterans, they require training to keep them constantly up to date with the new advances and the care that they must provide.

In recent decades there have been major developments in nursing, in both the academic and the clinical field. Technological advances in health and care have resulted in a need to define and acquire new professional competences.

The current requirements for access to the workplace are assymetrical, non-regulated and based solely on holding a degree in nursing and on time worked previously in a given department. Some studies claim that specialising in care improves care results, and therefore training should be ensured for specific jobs.1

Currently there is no official nursing specialisation in critical patient care in Spain. However, some universities do provide training in this area in the form of their own master’s and expert level qualifications. Many countries are developing training programmes in this regard, especially in light of the evidence provided by Aiken et al.,2 who found a relationship between the educational levels of nurses and patient mortality.

Although we are in the European Higher Education Area, the different solutions proposed by Lakanmaa et al.3,4 from Finland are not symmetrical to those that can be developed in the Spanish National Health System. In the area of critical patient care, different measuring instruments have been designed, such as the Intensive and Critical Care Nursing Competence Scale and the Basic Knowledge Assessment Tool, version 7,5 all of which came about from the needs detected in this respect by the European Federation of Critical Care Nurses Associations (EfCCNa)6 to homogenise intensive care in Europe. The need for training identified comes not only from the scientific societies, but also from professionals, who see gaps in training and information on specific competences. In this regard, the need can be seen for collaboration to obtain the best outcomes and optimal training adapted to the needs of the patient and the ICU environment.

For all these reasons, there have been different responses at a European level, all aimed at the acquisition of a series of competences ranging from the most technical, behavioural and emotional, with emphasis on communication. It has been observed that improved nurse training and professional working environments lead to better outcomes in complex patients.7–9

There have been attempts in Spain to develop accreditation as a specific or advanced area of competence by the Spanish Society of Intensive Nursing and Coronary Units, but this has remained an isolated attempt that has not gained the support of the public or private institutions that ultimately hire nurses in the different intensive care units.10

Even at the moment, we need to ask ourselves what the necessary competences in each unit are,3 and even assess what nurses themselves demand in the workplace,11–13 and not forget that continuous training is a bridge to care excellence, more so in highly technical units where potential risks are also associated with deficient training.14,15 Nurses, as members of a multidisciplinary team, require appropriate training to face the challenges posed by critical patients and their environment.

Based on the premise that training in advanced care is necessary, the aim of this research study was to describe the training needs detected by ICU nurses through their life and professional experience.

MethodA descriptive qualitative design was proposed, with a phenomenological approach. Phenomenology enables us to study the proposed phenomenon through lived experiences and analysis of the reality of work in the everyday environment of an ICU. This study was developed with the nurses of the adult ICU of the Hospital Universitario Insular of Gran Canaria, which comprises a polyvalent unit of 30 beds.

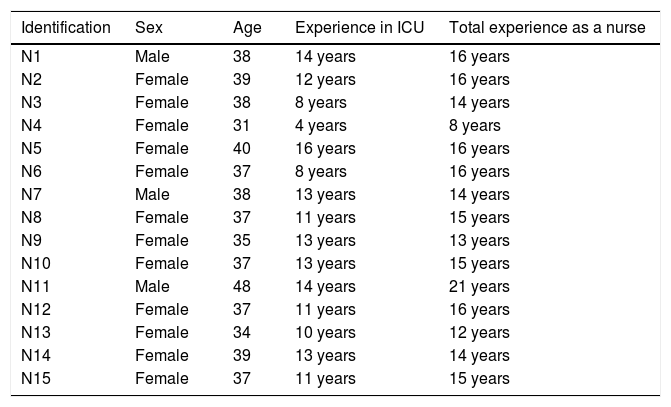

The sample to be studied was selected through convenience sampling of 72 nurses. Participants in the study had to have had experience in ICU of three years or more and collaborate in the study voluntarily and disinterestedly. The sample consisted of 15 participants; their distribution is shown in Table 1.

Socio-demographic data of the participants.

| Identification | Sex | Age | Experience in ICU | Total experience as a nurse |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N1 | Male | 38 | 14 years | 16 years |

| N2 | Female | 39 | 12 years | 16 years |

| N3 | Female | 38 | 8 years | 14 years |

| N4 | Female | 31 | 4 years | 8 years |

| N5 | Female | 40 | 16 years | 16 years |

| N6 | Female | 37 | 8 years | 16 years |

| N7 | Male | 38 | 13 years | 14 years |

| N8 | Female | 37 | 11 years | 15 years |

| N9 | Female | 35 | 13 years | 13 years |

| N10 | Female | 37 | 13 years | 15 years |

| N11 | Male | 48 | 14 years | 21 years |

| N12 | Female | 37 | 11 years | 16 years |

| N13 | Female | 34 | 10 years | 12 years |

| N14 | Female | 39 | 13 years | 14 years |

| N15 | Female | 37 | 11 years | 15 years |

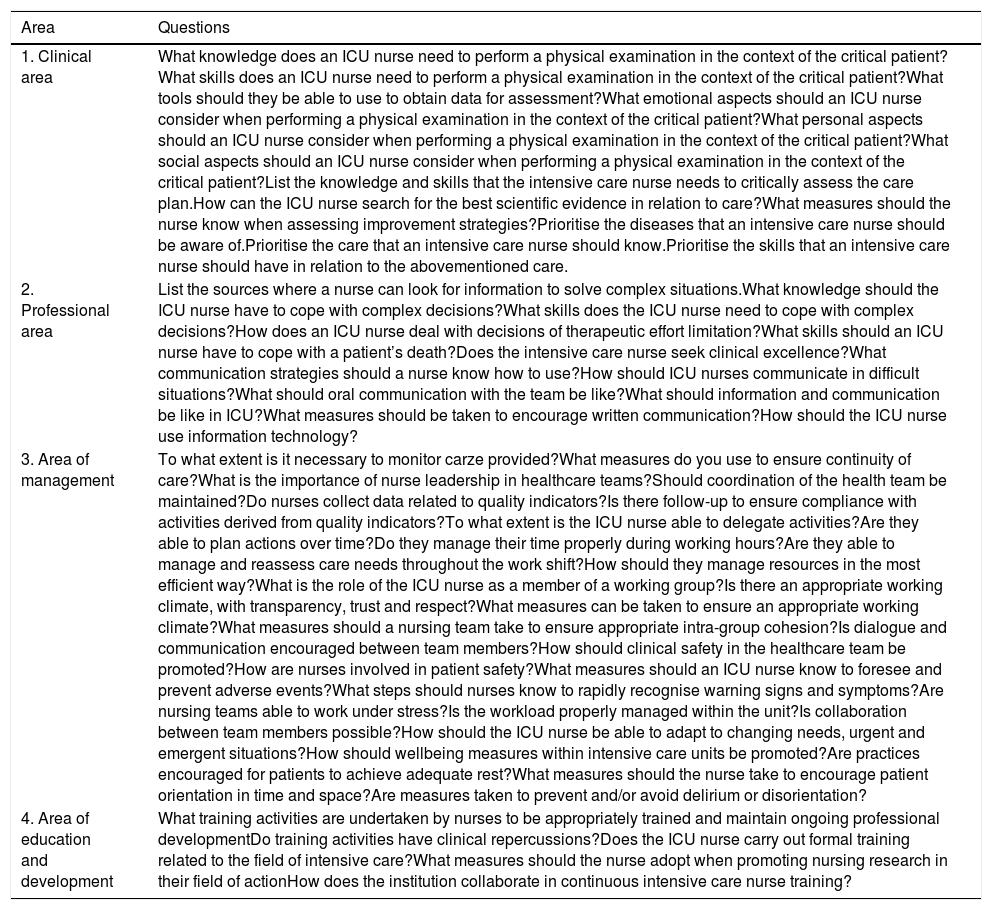

The semi-structured technique was used to obtain information, with 57 open-ended questions addressing the fields explored and developed by EffCNa,6 which are the following: clinical, professional, management and educational or developmental. They also included the dimensions of care as a cross-sectional axis of these areas such as: cognitive and learning, technical, integrative, relational and moral-affective. All the questions were included by consensus of the research team and supported by the current literature (Table 2).

Study questions.

| Area | Questions |

|---|---|

| 1. Clinical area | What knowledge does an ICU nurse need to perform a physical examination in the context of the critical patient?What skills does an ICU nurse need to perform a physical examination in the context of the critical patient?What tools should they be able to use to obtain data for assessment?What emotional aspects should an ICU nurse consider when performing a physical examination in the context of the critical patient?What personal aspects should an ICU nurse consider when performing a physical examination in the context of the critical patient?What social aspects should an ICU nurse consider when performing a physical examination in the context of the critical patient?List the knowledge and skills that the intensive care nurse needs to critically assess the care plan.How can the ICU nurse search for the best scientific evidence in relation to care?What measures should the nurse know when assessing improvement strategies?Prioritise the diseases that an intensive care nurse should be aware of.Prioritise the care that an intensive care nurse should know.Prioritise the skills that an intensive care nurse should have in relation to the abovementioned care. |

| 2. Professional area | List the sources where a nurse can look for information to solve complex situations.What knowledge should the ICU nurse have to cope with complex decisions?What skills does the ICU nurse need to cope with complex decisions?How does an ICU nurse deal with decisions of therapeutic effort limitation?What skills should an ICU nurse have to cope with a patient’s death?Does the intensive care nurse seek clinical excellence?What communication strategies should a nurse know how to use?How should ICU nurses communicate in difficult situations?What should oral communication with the team be like?What should information and communication be like in ICU?What measures should be taken to encourage written communication?How should the ICU nurse use information technology? |

| 3. Area of management | To what extent is it necessary to monitor carze provided?What measures do you use to ensure continuity of care?What is the importance of nurse leadership in healthcare teams?Should coordination of the health team be maintained?Do nurses collect data related to quality indicators?Is there follow-up to ensure compliance with activities derived from quality indicators?To what extent is the ICU nurse able to delegate activities?Are they able to plan actions over time?Do they manage their time properly during working hours?Are they able to manage and reassess care needs throughout the work shift?How should they manage resources in the most efficient way?What is the role of the ICU nurse as a member of a working group?Is there an appropriate working climate, with transparency, trust and respect?What measures can be taken to ensure an appropriate working climate?What measures should a nursing team take to ensure appropriate intra-group cohesion?Is dialogue and communication encouraged between team members?How should clinical safety in the healthcare team be promoted?How are nurses involved in patient safety?What measures should an ICU nurse know to foresee and prevent adverse events?What steps should nurses know to rapidly recognise warning signs and symptoms?Are nursing teams able to work under stress?Is the workload properly managed within the unit?Is collaboration between team members possible?How should the ICU nurse be able to adapt to changing needs, urgent and emergent situations?How should wellbeing measures within intensive care units be promoted?Are practices encouraged for patients to achieve adequate rest?What measures should the nurse take to encourage patient orientation in time and space?Are measures taken to prevent and/or avoid delirium or disorientation? |

| 4. Area of education and development | What training activities are undertaken by nurses to be appropriately trained and maintain ongoing professional developmentDo training activities have clinical repercussions?Does the ICU nurse carry out formal training related to the field of intensive care?What measures should the nurse adopt when promoting nursing research in their field of actionHow does the institution collaborate in continuous intensive care nurse training? |

After personal contact with the respondents, a date, time and place were agreed for the interview to take place. The appointments were flexible to avoid setbacks for the participants. At the start of the recording the study was explained to the respondents, they were thanked for their participation and asked to give their verbal consent. They were also reminded that the interview was being digitally recorded and that the recordings, not including personal data, would only be used for research purposes in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and Organic Law 15/1999 on Personal Data Protection and its subsequent update in Organic Law 3/2018.

The total duration of the interviews was 17h 4min and 16s, with a minimum of 50:26 and maximum 1:44:25. All the interviews and incidents were recorded in the field notebook. The interviewer was known to the respondents. The investigators, before the start of the interview, agreed not to intervene in the respondents’ discourse, not to contribute with their personal views and to read the questions from a single script designed for the purpose.

Analysis of the information collected was carried out as proposed by Cisterna-Cabrera,16 a hermeneutical triangulation procedure: “select the information obtained in the fieldwork; triangulate the information by each level; triangulate the information with the data through the other instruments and; triangulate the information with the theoretical framework”.

Triangulation was carried out by first combining the information gathered from the recordings, the field notebook among the first,4 investigators: this was a preparation phase. In addition, the topics on which the interview was based were identified, the investigators were given a script to identify each topic. Each of the investigators, listened to all the recordings personally, drew their personal conclusions adapted to the topics, coding the responsesalso suggested by other authors such as|as, Taylor, Bogdan.17 This made it possible to create analytical categories that were subsequently analysed by means of an inferential procedure with bottom-up conclusions related to areas of consensus, divergence among the respondents. Three consensus meetings were held to validate the investigators’ conclusions focussing on maintaining the descriptive validity of the discourses expressed, with verification of the initial discourse with the investigators’ conclusions. As, the meetings were held, the most pertinent verbatims were indicated to assess the needs detected by the nurses in their training in the area of intensive case, included in each analytical category. The consensus strategies were to validate the information collected, adapt it to the included category, re-read it once reorganised to check that it had the same meaning as, expressed by the respondent.

To ensure quality and rigour, reflexivity was used as a positive analytical element, clearly identifying throughout the study, the role of the investigator and their influence on both the data collection and analysis. The members of the research team took their own internal and external assumptions into account when analysing the data in order not to cause changes to the information provided by the interview respondents. The reflexivity procedure enables redundancies in discourses to be eliminated, relevant meanings to be grouped, literal transcription in the text of this manuscript of the experiences most relevant to the study aim, and what we consider most important in understanding what the respondents said and not what we expected them to say. The objective of this study was to describe the training needs detected by ICU nurses through their personal experiences. The reflexivity procedure enables not only the training needs of ICU nurses to be identified but also facilitates framing of these needs within the competence framework as described by the EfCCNa. Reflexivity allows us to meet the objective of the study. This allowed us to vary and model the conclusions of the research team. Data saturation and validation by the informants during the interview process were evaluated to assess whether the information was sufficient.

The confidentiality of the informants was ensured by assigning an alphanumeric code during the interview, N1 and consecutive mode, which were not identified during the interview.

This study was approved by the Deontological Commission of the Universitat Jaume I. The recordings and consents will be kept by the principal investigator for 5 years, which is the time of scientific production stipulated by the commission and will then be destroyed.

ResultsIn order to analyse the information correctly, we used the areas of competence as described by the EfCCNa.

Competences of the clinical fieldWhen assessing this area, the experience of the nurses indicates that a very high level of knowledge and sufficient capacity to apply it sequentially is required. This implies having sufficient skills to enable the assessment, care and follow-up of patients. Hence, according to the different comments, the importance of observing parametric and non-parametric values and go from observation to the most advanced monitoring to date. Special emphasis is placed on monitoring and the application of scales, as a preliminary step in applying professional reasoning towards implementing quality care. “Knowledge of what is going to be done and what is being sought, to be able to implement care efficiently (…) a nurse cannot deliver care without knowing exactly whether or not it is appropriate at that moment in the process. To provide good care you have to know what’s happening” (N5). “You have to know what you are looking for, to know about what you find and to know how to analyse it, and for this you need tables, experience and previous training. In addition to re-assessing, which for me is the most important thing that ICU nurses have to do continuously” (N9). “In ICU you have to use many tools that are not taught during the degree, and therefore new staff can feel more helpless and stress during their shifts (…) and this is reinforced because there are many diseases in ICU, because patents don’t usually have just one disease, you also have to know how to care for from pneumonia to malaria and implement the appropriate care and controls” (N14).

An outstanding aspect is the need to provide emotional and psychological support in this type of patient, through professional awareness of the circumstances surrounding this type of healthcare, where the hospital environment becomes especially hostile with the large amount of noise, whether alarms, voices or the use of so many devices that users are not familiar with. Therefore, many of the respondents referred to the importance of empathy and recognising how both users and family members can feel in this environment. It is also striking how they assume that aspects of emotional or psychological care are usually postponed, as they illustrate: “Perhaps it is a mistake on my part, but I prioritise stabilising the patient to finding out about emotional issues” (N13). “At first, the psychological aspect is rather left to one side, because we do not treat it as something urgent, when the patient is already stable and, generally, these are long stay patients, then we do return to that aspect of care, but it is left to one side a little at first.” (N12).

From a personal point of view the respondents acknowledge that when they started their work in ICU, they were not emotionally or instrumentally prepared to deal with the pressure of critical situations in an ICU. “From day one you lack these skills unless you’ve done best practice (…) and this is a really stressful situation when trying to undertake a work activity that is often delicate” (N3). “Everything necessary to take care of critical patients is acquired, going to an ICU on the first day to work without extensive previous training (…) bearing in mind that not all nursing students have been through an ICU and not all of them have developed suitable practice to then cope from the first day you’re hired you’re let loose to care for critical patients, there are episodes of insecurity and anxiety” (N8).

When talking about indispensable care, the respondents list a great deal of complex care. There is consensus, however, that the most important thing is to know each patient’s care plan, and be able to implement it, bearing in mind that: “Technical skills are important, but an early response to complications themselves, to treatment and care is essential. An ICU nurse must be very reflective of what is happening and what could happen and appropriately correlate all the data available to them”(N6). “It is important to know how to prioritise with critical patients (…) the ICU nurse must adapt and perhaps this is one of the most important features of the intensive care nurse” (N1).

It can be seen how support measures, pharmacological or otherwise, as well as monitoring measures, should be known in detail. Special emphasis is placed on knowing how to handle, monitor and act with mechanical ventilation. The clinical entity emerges in the form of a dichotomy: what should be done and what not? To this end, a large number of competences must be the basis. “For me it is important that they do not develop pressure ulcers, but this also clashes with haemodynamic or respiratory stability” (N11). “Adapting the therapeutic plan-care plan to the current reality of users is a continuous challenge for nurses” (N6).

In the professional field, the respondents state the importance of continuous training and the capacity to collaborate between professionals. Experience among the nurses themselves, becomes an essential axis to solve complex situations in the different work shifts. “Always consulting colleagues or the pharmacist on issues of drug administration, rather than causing an error or adverse event in the patient’s care” (N2). “Consulting colleagues is the fundamental source, if I’m not happy with this then I would consult the Internet (…) but generally experienced nurses have most of the answers and tend to be the most appropriate sources, if not the doctor on call. We’ve also sometimes looked for solutions among us all”(N5).

In order to work safely, they mention that a great deal of training and specialisation is necessary, and recognise that undergraduate training only provides very basic skills and abilities for what is required in ICU. And they restate what was said in the clinical field, and add: “All decisions are complex in intensive care, ant this is why appropriate training is necessary before working in ICU” (N8). “Nurses make a lot of decisions here, because we have a lot of autonomy” (N10).

In ICU, nurses face situations in the professional environment that have undoubted repercussions at a personal level, such as the death of a patient or decisions on limitation of therapeutic effort (LTE). They assume that this is a very personal situation, and they do agree on two things, that these decisions basically stick with them, are considered a passive element and that they would cope less well emotionally with more aggressive treatment. In addition, with respect to the death of patients there are cases where, due to the special characteristics of these people, they are more affected, especially due to the personal involvement that is associated with care.

We are talking about medical judgement (LET) where the nurse has no other option but to comply with the situation, although it is always possible to contrast and check the information so that there is no problem or cross information. It is necessary to come to terms with it, stick with it and re-assess the situation by adapting the care plan” (N1). “It is not so hard for me personally to face a therapeutic limitation that you see clearly and yes the fury that it often causes. I find the patient’s agony more difficult to face” (N2).

Within the care team, they mention living in stressful situations that affect communication between professionals. They recommend learning communication by means of simulations and that this has to be clear, concise and specific, without shouting and with objective data, emphasising bidirectional, fluid and inclusive communication. “With a calm voice, without losing one’s cool” (N13). “The message you want to give and to whom must be clear, with the aim of solving the situation and not creating further problems” (N4).

In addition, they observe shortfalls in communication with respect to family members: "We must not forget that nurses also have to give information and we do not know how to inform about our field of action" (N15). “Often after being informed, families run off to look for someone to explain how their relative is doing and it’s generally the nurse who answers these queries and that is why it is important to communicate with the team and to give family members accurate information at all times.” (N11).

Many of the respondents see continuity of care as one of the great strengths of the ICU. Follow-up is linked as an obligation of professionals that might constitute one of their greatest weaknesses, since non-compliance leads to loss of that strength. Continuity of care is defined as essential. Records of the activities and assessments of all the professionals included in the patients’ care are considered an essential axis to achieve this care objective. Continuity of the nursing sessions that are held first thing in the morning shift also strengthens and ensures continuity. “Knowing how the users are should be based on both written and verbal information, as well as relying on all the members of the team, other nurses and/or nursing assistants who already know the patient’s situation, or events that have happened on other days” (N7).

As for the importance of nursing leadership, they believe that there is informal leadership within the healthcare team. “As nurses we do not believe the importance we have in an ICU and if were to believe it more, we would be leaders in more things” (N13).

With regard to quality in management, the nurses mention that quality indicators are collected and it is considered a non-essential element of their daily work, a lot of data and indicators are wasted. They also change it into a matter external to them as professionals, and according to the respondents, this responsibility falls to the quality department. “Quality indicators are followed when possible and that doesn’t happen very often” (N5). “A lot of data are wasted because we go to immediate health care and that’s why we leave these data to one side” (N1).

They state that teamwork is also necessary, especially when delegating activities or using human and material resources and they acknowledge that the ICU must form a cohesive and responsible work team: “ICU assistants do quite a few things that they would not do on the ward and this is a value within the health team, even though nurses have to be present continuously”(N3). “Nurses have to be attentive at all times, to cope with everything that happens” (N12). “Trust and the working environment have a lot to do with the people you work with, with their personality and especially with their experience and skills, from the doctors to the hospital porters” (N5). “New nurses are often ignored by the medical team, because they don’t consider them worthy of sharing the care plan and this can become a weakness in health care” (N6).

When looking for situations for improvement they again insist on the need for gradual and regulated learning, management should maintain and reflect on decisions made, so that clinical safety is not compromised. “It should not be permitted for 17 inexperienced nurses to suddenly cover shifts, as happened (…) a lot of new staff, without people with experience, makes patient safety a delicate issue” (N14). “Management decisions have made us train and work continuously under stress and not only are we able to work under stress but we are also specialists (…) you also have to take care of other new colleagues who are willing to get the job done but require a veteran to guide them” (N6). “Taking on the care burden, being able to help colleagues and successfully complete a shift has a lot to do with training and especially with experience that equips you to deal with almost anything that is thrown at you” (N9).

In this area, the ideas expressed under the other headings are stressed on the need for ICU staff to be continuously trained, but three factors are observed: the lack of prerequisites, lack of a specific ICU training plan and the subjectivity of each nurse’s interests. These are considered weaknesses that need to be addressed and improved. “Each unit should have its specific training with the needs detected and have its own sessions provided by experts for both new and old (staff)” (N14). “You need to be very willing, and make time from your own personal time for self-training” (N6). “The institution collaborates relatively little because it provides very general training, and ICU if anything is very specific in the training needs required by nurses and all professional staff (…) a thousand things are used here that are not used in the rest of the hospital” (N11).

If training is difficult, in the context studied, research is considered secondary and not valued at all in the work environment, therefore research areas should be encouraged through awards or grants. “We might be losing very valid people, because we’re not committed to people who do research”(N12). “Nurse research is considered secondary and is not included in their contracts with the company, and therefore only highly motivated nurses research in their free time and that is a loss for the System” (N7).

If we assess all the areas of this article together, we can see that the respondents place major emphasis on ICU being a highly complex department, which goes beyond any undergraduate training received. In this context they link experience as essential, but they associate the needs for very extensive training to face daily care challenges. There is also insecurity on the part of novice nurses in approaching certain departments such as ICU.18,19

Skees14 approaches the need to develop continuing education to achieve excellence, enabling nurses to care safely, achieving better outcomes, helping them increase their knowledge and develop their critical thinking. All of this should focus on the needs that are detected in specific areas, as our respondents express.

A lack of training in certain fields is observed that, if we follow the study by Gallaher,20 must be adapted through regulated programmes, aimed at improving health care, detecting the areas of care that must be implemented through specific educational programmes. The needs found can be met through the use of tools of proven usefulness, as with online education21 for certain types of training, since the respondents themselves acknowledge that experience gained in the ICU itself is very didactic.

The participants in this study observed the need, in turn, to progressively tutor novice nurses, and to consider theoretical/practical education with the help of clinical simulation, already addressed by Thomason22 that highlights the preparation of novice nurses with a complete and specific programme,4,23 which should be an objective of the units themselves and the health system to enable nurses to cope with care in a progressive and safe manner. This would enhance health care especially in clinical safety, since as Ania-González et al.24 detected, nurses have better knowledge than that they demonstrate in practice, in techniques such as secretion suction, this finding can be extrapolated to other care. The abovementioned can be applied to novice nurses as well as veterans with needs for retraining, or to approach new therapies and care. As has been demonstrated and as assessed by our sample as a point for improvement, continuous training will always be needed to enable efficient preparation for these types of care areas.25–27

As Currey et al.26 mention, being able to become trained is an opportunity to work in a team, which is highlighted as a fact to be reinforced in care teams. It is observed in the literature consulted, and the sample, that new roles and responsibilities are taken on every day, which results in our creating new experiences that vary the concept of ICU nurses, through dealing with new therapies and roles. The aim of acquiring care skills must always be delivering successful care, which depends very much on the development and skills of nurses in caring for critical patients.2,26,28

The paradigm of critical patient care is currently being modified, since including family members as elements of success in the care process has now been assessed,29 which was not previously considered a primary function, and even leaving the units and extending nursing care with other roles that ensure continuity of the care started in the ICU.30 These changes in action must be accompanied by training and clinical practice guidelines that have been agreed between team members. This highlights the reality, increasingly pressing, that more clinical competences must be acquired,13,31 and that ICU is a continuously evolving scientific environment.32 This acquisition of knowledge and this scientific evolution must motivate greater involvement of the health authorities33,34 towards achieving training policies that are increasingly focussed on the demands of nurses. The positive aspect of postgraduate training in this area has even been assessed in some studies, as observed by Cotterill-Walker35 in their literature review, which supports the comments of the participants in this study.

In light of what is much highlighted in this study, working in stressful situations and the need for continuous change due to the specific needs of critical patients, and nurses’ ability to prioritise when delivering care were very positively assessed. It was observed that general communication,36 and specifically in complex or critical situations, is an essential area that must be developed in order to avoid errors and achieve appropriate outcomes, through group dynamics in the care teams themselves.

Furthermore, our respondents acknowledge that it is difficult to address the situations of patients who die in the units, and that not all cases are experienced in the same manner. It is observed that long stays37 lead to greater acceptance of limitation of therapeutic effort due to the low survival rate. Gálvez-González et al.,38 in a similar sample to ours, state that nurses require training to be able to share decisions on LTE and cease to be a passive entity in decision making, this passivity is also expressed by our respondents. This need must be developed through the acquisition of competences in this field.12

In the area of management, training and development, the nurses we consulted acknowledge that it is necessary to make decisions that guide both the workload of the unit and the nurses’ training plan, to improve areas of work39 and welcome new staff, in a progressive and effective manner.40–42 All this will generate better health outcomes,2,7,8 fewer errors in health care.20 In a global context, self-assessment of the professionals themselves should be extended which could lead us to areas for improvement in the different nursing competences that are required on a daily basis in an ICU.43

ConclusionThe sample studied places special emphasis on the fact that solid knowledge and skills are required to care effectively for intensive care unit users. In this regard, they acknowledge that continuous training is necessary, and that the knowledge they had when they graduated from university was not sufficient to care for critical patients adequately. A great deal of experience and specific training is required to care in an effective way.

In relation to the care of critical patients, the clinical field has been associated with a need for training that adapts to the reality of the ICU environment and the needs of different types of patients. Based on general competences applicable to all critical patients, the importance is highlighted of examining more specific competences in depth that ensure care in more specific cases.

In the area of management, three needs are observed: to manage personnel and workload appropriately, use materials efficiently and nurse leadership. The multidisciplinary team is highlighted as a fundamental axis that must be promoted and supported by both professionals and managers.

For all these reasons, we propose the creation of studies that focus on the competences that need to be developed in each ICU unit, we must know what is required of a nurse, and ensure competence in this field. In addition, the objective must not just be to act, but to act in the most excellent way possible.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Santana-Padilla YG, Santana-Cabrera L, Bernat-Adell MD, Linares-Pérez T, Alemán-González J, Acosta-Rodríguez RF. Necesidades de formación detectadas por enfermeras de una unidad de cuidados intensivos: un estudio fenomenológico. Enferm Intensiva. 2019;30:181–191.