Pain assessment and treatment are essential for ensuring quality of care as well as for improving patient's satisfaction and clinical outcomes.

Objectives(1) To describe pain perception of surgical patients admitted to our intensive care unit (ICU). (2) To compare the patients’ pain perception with the assessment carried out by nurses. (3) To correlate International Pain Outcomes Questionnaire results with socio-demographical data.

MethodologyA prospective descriptive observational study was carried out in the ICU of a third level university hospital over a period of 3 months.

Surgical patients’ pain-perception was assessed 24h after their admission to the ICU using the Spanish translation of International Pain Outcomes Questionnaire.

ResultsThe highest pain score recorded among 109 patients by nurses was 4.47±2.75, while, the lowest was .69±1.25. However, the highest and lowest pain scores reported by patients were 5.59±2.72 and 2.13±2.03, which showed significant differences (p<0.001).

The highest pain score seemed to be related to the type of surgery (p<0.027).

There are significant variations in the lowest pain score depending on age (p=0.005, r=−0.270). Likewise, the worst pain score correlated with the patients’ sex (p=0.004).

Patients who reported that pain made them feel very anxious or helpless scored highest with the worst pain, 7.35±1.98, 7.44±1.85 respectively. These differences were statistically significant (p=0.001, p<0.001). Regarding to the score of less pain, there is an association with feeling anxiety (p=0.032) and not with feeling helpless (p=−0.088).

ConclusionsThe post-surgical patients reported pain during the first 24h following admission to ICU (max score 5.59±.26).

The nurses underestimated the patients’ reported pain. Improving nurses’ education would provide them with assessment strategies for better pain management.

Age, sex, anxiety and helplessness caused by pain, were variables that significantly influenced pain.

La evaluación y tratamiento del dolor es imprescindible para una atención de calidad, además de para mejorar la satisfacción del paciente y los resultados clínicos.

Objetivos1) Describir la percepción de dolor de los pacientes posquirúrgicos ingresados en nuestra Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos (UCI). 2) Comparar la percepción del paciente con la valoración realizada por la enfermera. 3) Comparar los resultados de la encuesta International Pain Outcomes con los datos sociodemográficos.

MetodologíaEstudio descriptivo prospectivo observacional en la UCI de un hospital universitario de nivel terciario durante 3 meses. Se estudió la percepción del dolor en los pacientes posquirúrgicos, a las 24h de ingreso en la unidad, a través de la encuesta International Pain Outcomes traducida al español.

ResultadosLa puntuación de mayor dolor registrada de los 109 pacientes fue 4,47±2,75 y la de menor de 0,69±1,25 frente a 5,59±2,72 y 2,13±2,03 que refirieron los pacientes, con diferencias significativas (p<0,001).

La puntuación del mayor de dolor registrado está relacionada con el tipo de cirugía (p=0,027).

Hay diferencias significativas en la valoración del menor dolor y la edad (p=0,005 r=−0,270). Igualmente sucede con el sexo y la percepción de mayor dolor (p=0,004).

Los pacientes que refirieron que el dolor les hizo sentir muy ansiosos o indefensos fueron los que tuvieron las mayores puntuaciones en la percepción de mayor dolor, 7,35±1,98 7,44±1,85, respectivamente, con diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p=0,001; p<0,001). Con relación a la puntuación de menor dolor, se encuentra asociación con el sentimiento de ansiedad (p=0,032) y no con el sentimiento de indefensión (p=0,088).

ConclusionesLos pacientes posquirúrgicos refieren dolor durante las primeras 24h de ingreso en la UCI (puntuación máx 5,59±2,72).

Las enfermeras infravaloran el dolor que el paciente refiere. Una formación adecuada ayudaría a dotar estrategias de valoración para un mejor tratamiento.

La edad, el sexo, la ansiedad y la indefensión que el dolor provoca fueron variables que condicionaron el dolor de manera significativa.

Pain is one of the major concerns and principal agents of stress in hospitalised patients. It is a complex and multidimensional concept which triggers multiple reactions that affect patient evolution. The evaluation and treatment of pain is essential for quality care and also for improving patient satisfaction and clinical results. However, the complexity of pain hinders its assessment.

What does this paper contribute?The aim of this study is to determine the patient's level of pain and the assessment made by the nurse to know whether the pain has been appropriately assessed. It also aims at detecting the most influential factors governing the perception of that pain. Once the most influential factors are known regarding both assessment and perception, care plans may be established to improve the perceived pain.

This study has enabled the patient's level of pain to become known and to compare it with the computerised register, as well as detecting the most influential factors involved in order to tackle them. Identifying whether the assessment is correct and which factor most affect pain is the first step towards attempting to apply corrective measures which, according to our results, should be: greater nursing training for correct assessment, recording and treatment of pain, and obtaining prior information on the factors which our study shows have conditioned that pain. The perception of postoperative pain would thus be better understood and treatment individualised and optimised.

IntroductionOne of the main concerns and principal agents of stress in hospitalised patients is pain.1–3 The International Association for the Study of Pain4 defines if as “an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage”.

Pain is an individual experience. There are many reasons a patient may present with pain: the disease itself, which causes their hospitalisation; hygiene and care techniques; changes to position; the patient's own immobility; dressing changes.5–8 Furthermore, standard procedures such as the removal of endotracheal tubes, aspiration of secretions, peripheral catheterization or the removal of chest drains increase patient pain.6,8 Factors such as age, cognitive status, emotional state and previous painful experiences affect the patient's perception of the pain and convert it into a complex and multidimensional concept.8–11

In 1996, the American Pain Society introduced the concept of pain as the “fifth vital sign” in order to dispose of more opportunities for it to be properly assessed, treated and recorded.12 Although pain management requires a multidisciplinary team, the nurse is in a unique position to assesses and continuously control it6,10,13 due to his or her constant proximity to the patient and because he or she is the professional who most frequently applies techniques to it. However, since pain is a multidimensional variable, assessing it is difficult and may lead to discrepancies between how the professional interprets it and the patient's own reference to it.14,15 Although several validated methods are available,16 professionals tend to focus exclusively on physiological or behavioural changes that the pain may provoke and attach less importance to what the patient is actually communicating.14,17

Pain assessment and treatment is essential for quality care, in addition to improving patient satisfaction and clinical results, such as the reduction in ventilation periods, hospital stay, stay in the intensive care unit (ICU), and improvement of survival.1 Pain control must be a social and health priority and the degree of relief is considered an indicator of efficiency and quality.10,11 Assessment and effective management should be one of the main aims worldwide.18–20

Postoperative pain is defined as acute pain in response to surgical aggression and is considered an uncountable reality linked to surgery and the postoperative period.21 At present, acute postoperative pain persists as a symptom of raised prevalence and its inappropriate treatment as one of the main predictors of chonicity.13,22,23 Postoperative pain in patients in the ICU has a prevalence of 40–77%.14 After an operation pain triggers inflammatory reactions which may affect patient evolution.13,24 The most frequent are respiratory (atelectasis, pneumonias and hypoxaemia) and circulatory changes (high blood pressure, tachycardia, increased organic demand for oxygen and myocardial ischaemia). Several authors state these are the most important causes of mortality, at 23%21 and 25%, respectively.25 Other reactions to bear in mind are psychological in nature, such as anguish, fear, depression and apprehension.3,26

In response to the above this research has been conducted with the following objectives: (1) describe the perception of pain of post-surgical patients in our ICU; (2) compare the perception of the patient with the assessment made by the nurse; (3) analyse the results from the International Pain Outcomes questionnaire (IPO) with sociodemographic data.

MethodologyThis descriptive, prospective, observational study was conducted in a multipurpose ICU with 12 beds, belonging to a tertiary private university hospital with 300 beds. Between 1,000 and 1,200 patients are admitted to this unit annually, around 80% of which have undergone surgery. The most common types of surgery the patients are admitted to the unit for are heart and chest surgery, general surgery, urology, vascular surgery and neurosurgery. This study was conducted between November 2017 and February 2018.

To calculate necessary sample size for this study the mean value of the postoperative pain was taken into account using the IPO questionnaire.27 The study would require a sample of 127 post-surgical patients to estimate the mean score of the worst pain suffered in the first 24h of post-surgical patients in our ICU, with a precision level equal to .5, a 95% confidence level, potential losses of 5% and an expected standard deviation of 2.8. Our convenience sampling finally comprised 109 patients. The calculation considered occupancy data from the previous year. However, these data did not coincide with the collection period, and our sample was finally lower than the estimated one.

Inclusion criteria for sample selection were: that the patients had undergone surgery within 24h prior to ICU admittance and that they were extubated at the time of the interview. They had to be conscious and fully aware (information on level of consciousness and awareness of patients was obtained from the computerised medical record registered at the end of each shift) and able to speak and understand Spanish. Exclusion criteria were: patients who had been incubated over 24h; those who were unable to communicate; those who presented with some type of mental, cognitive or sensory impairment which could hinder correct application of the questionnaire and patients who presented with confusion during their stay in the ICU, according to the results obtained from CAM-ICU delirium scale.

Variables and tools used in data collectionThe research team created a document consisting of 2 sections:

- •

Variables: data from the patient's medical file and from the computerised nursing care plan. The following were recorded:

- ∘

Age, sex, educational level, type of surgery.

- ∘

If it was primary surgery and first time stay in the ICU.

- ∘

Higher and lower numerical assessment scale of the pain recorded during the first 24h. It is one of the most well-known and accepted pain assessment scales. It tries to convert the patient's own perception of pain into quantitative variables which may, depending on their grading, suggest the idea of pain intensity. Grading of the scale ranges between 0 (no pain) and 10 (the maximum bearable pain).16

- •

Tools: IPO questionnaire translated into Spanish to determine the subjective perception of the patients’ pain (Appendix 1). This is a questionnaire validated at an international level with a high internal dependability (Cronbach α of .86) as shown by its authors).27 The questions refer to the intensity and frequency of pain, and also to interference in physical and emotional aspects. Also, side effects relating to treatment and their relief. Also, the participating in decision-making related to pain, the level of satisfaction with treatment used and whether the patient received information on the different options. The last questions probe on the frequency and usage of non pharmacological methods and whether previous pain of over 3 month's onset had presented prior to surgery.

The patient had to grade the questions from 0 to 10. In the first 6 questions a score of 0 indicated that the patient had no pain or it did not have any impact on their activities and a score of 10 was that pain did exist and that it completely interfered with activities. From question 7, a score of 0 indicated that information, relief, and participation was neither useful nor effective and a score of 10 showed complete relief and satisfaction.

Like other authors, we considered that the patients had a slight to moderate pain level when they gave a score of 0–3, a moderate to serious pain with a score of 4–6 and intense at ≥7.8,9,28

Similarly, we translated the numerical values of participation, anxiety and helplessness to qualitative interpretations. Assessment of anxiety was studied by different authors,29,30 but none of them used a similar scale to that used in our study. With regard to participation and helplessness, the same occurred. For this reason we grouped the scores into 3 scales (little, light or high) (terciles of assessment) trying to maintain as high a homogeneity as possible regarding score distribution. We thus considered that the patient had participated little when they gave a score of 0 and 3, lightly from 4 to 7 and highly from 8 to 10. With regard to anxiety and feeling helpless, this was considered low at 0 to 2, light from 3 to 6 and high from 7 to 10.

Data collectionData collection was performed by the research team for 3 months, with each of the patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria. A few hours after admittance and when the patient was without pain, the aim and importance of the study was explained to them and their request for participation was made. If the patient was admitted at night, this explanation was left until the following morning. If they were in pain, we waited until they were without it. If they gave their free consent, 24h after admittance into the unit a member of the research team collected data from the computerised nursing care plan and the patient questionnaire and ensured that each item/question had been understood. If the patent requested it, they were helped to complete it.

Data analysisFor quantitative data analysis descriptive and inferential statistics were used. Values were expressed as mean±standard deviation of the mean (SD), and the categorical variables as number and percentages. To analyse the difference between the 2 groups, the Student's t-test was used for non paired samples, provided that they showed normality (Shapiro–Wilks test). If the contrary was the case a non parametric test was used (the Mann–Whitney U-test). To analyse the difference between more than 2 groups, the Anova test was used in the case of parametric variables and the Kruskal–Wallis test in the case of non parametric variables. Categorical variables were studied using the chi-square test or the exact Fisher test. Correlations between continuous distribution variables were assessed using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Statistically significant differences were considered at p<.05. Statistical analysis was made using the SPSS (version 20.0) statistical programme.

Ethical considerationsApproval from the hospital Ethics Committee was obtained and authorisation to access the computerised medical history of the patients. These data were exclusively used for this study. All participants were guaranteed anonymity, complete confidentiality of data, and the destruction of questionnaires on terminating the research study. Written consent was obtained from the participants.

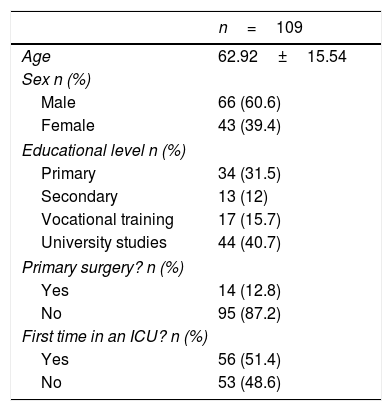

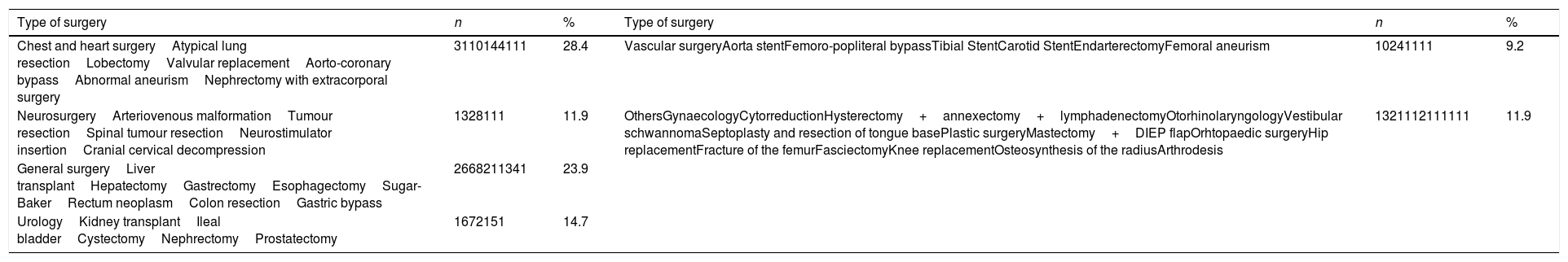

ResultsThe sociodemographic data of the sample are presented in Table 1. The type of surgery the patient was admitted for is contained in Table 2.

Sociodemographic data.

| n=109 | |

|---|---|

| Age | 62.92±15.54 |

| Sex n (%) | |

| Male | 66 (60.6) |

| Female | 43 (39.4) |

| Educational level n (%) | |

| Primary | 34 (31.5) |

| Secondary | 13 (12) |

| Vocational training | 17 (15.7) |

| University studies | 44 (40.7) |

| Primary surgery? n (%) | |

| Yes | 14 (12.8) |

| No | 95 (87.2) |

| First time in an ICU? n (%) | |

| Yes | 56 (51.4) |

| No | 53 (48.6) |

Description of types of surgery.

| Type of surgery | n | % | Type of surgery | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chest and heart surgeryAtypical lung resectionLobectomyValvular replacementAorto-coronary bypassAbnormal aneurismNephrectomy with extracorporal surgery | 3110144111 | 28.4 | Vascular surgeryAorta stentFemoro-popliteral bypassTibial StentCarotid StentEndarterectomyFemoral aneurism | 10241111 | 9.2 |

| NeurosurgeryArteriovenous malformationTumour resectionSpinal tumour resectionNeurostimulator insertionCranial cervical decompression | 1328111 | 11.9 | OthersGynaecologyCytorreductionHysterectomy+annexectomy+lymphadenectomyOtorhinolaryngologyVestibular schwannomaSeptoplasty and resection of tongue basePlastic surgeryMastectomy+DIEP flapOrhtopaedic surgeryHip replacementFracture of the femurFasciectomyKnee replacementOsteosynthesis of the radiusArthrodesis | 1321112111111 | 11.9 |

| General surgeryLiver transplantHepatectomyGastrectomyEsophagectomySugar-BakerRectum neoplasmColon resectionGastric bypass | 2668211341 | 23.9 | |||

| UrologyKidney transplantIleal bladderCystectomyNephrectomyProstatectomy | 1672151 | 14.7 |

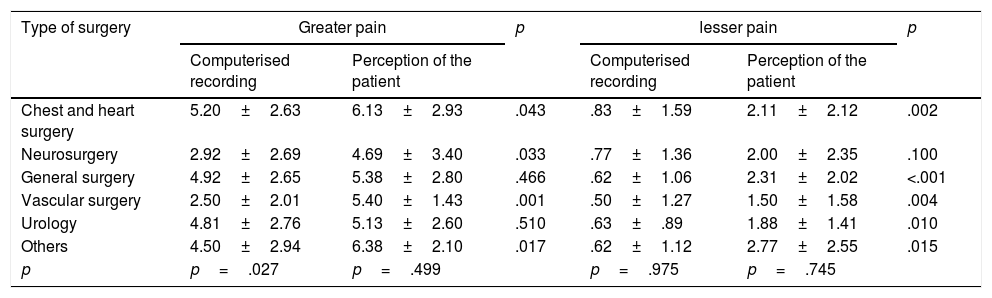

The highest pain score recorded was 4.47±2.75 and the lowest was .69±1.25 compared with 5.59±2.72 and 2.13±2.03 referred to by the patients. On comparing the recording with the perception of the patients, statistically significant differences were found in both measurements (p<.001). If we compare surgery with the recording and with patient perception, we find associations exclusively in the recording of the highest pain recording (p=.027). The type of surgery conditions the highest pain recorded. Table 3 shows the comparison between the patient's pain perception and the computerised recording by surgery.

Comparison between perception and recording by surgery.

| Type of surgery | Greater pain | p | lesser pain | p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Computerised recording | Perception of the patient | Computerised recording | Perception of the patient | |||

| Chest and heart surgery | 5.20±2.63 | 6.13±2.93 | .043 | .83±1.59 | 2.11±2.12 | .002 |

| Neurosurgery | 2.92±2.69 | 4.69±3.40 | .033 | .77±1.36 | 2.00±2.35 | .100 |

| General surgery | 4.92±2.65 | 5.38±2.80 | .466 | .62±1.06 | 2.31±2.02 | <.001 |

| Vascular surgery | 2.50±2.01 | 5.40±1.43 | .001 | .50±1.27 | 1.50±1.58 | .004 |

| Urology | 4.81±2.76 | 5.13±2.60 | .510 | .63±.89 | 1.88±1.41 | .010 |

| Others | 4.50±2.94 | 6.38±2.10 | .017 | .62±1.12 | 2.77±2.55 | .015 |

| p | p=.027 | p=.499 | p=.975 | p=.745 | ||

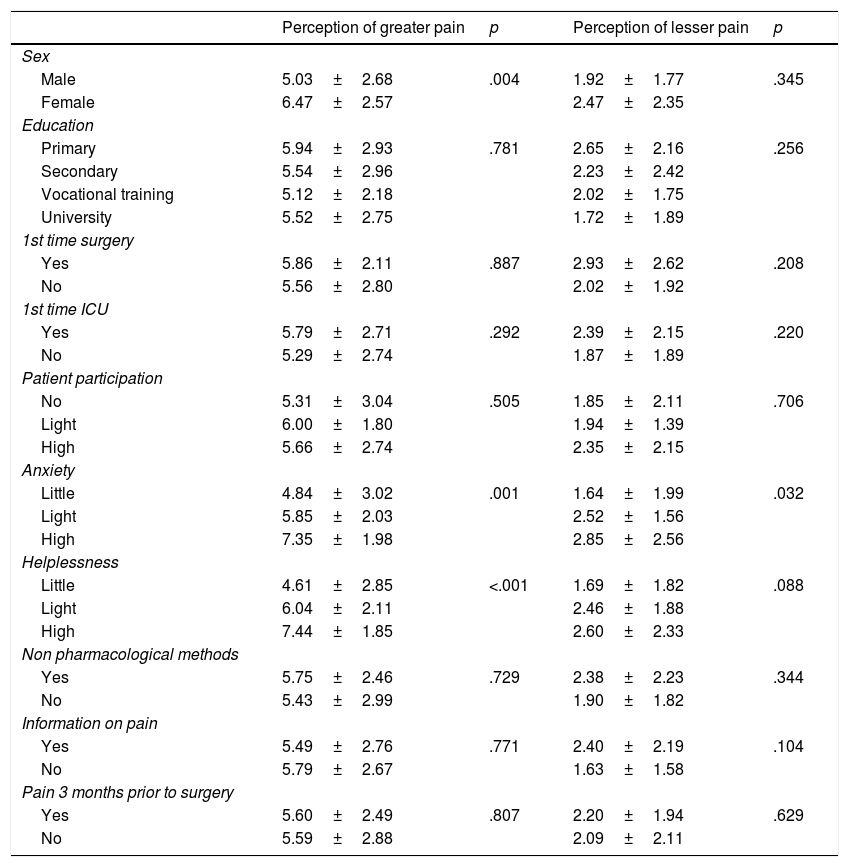

On comparing age and perception of pain, there are significant differences in the score of the least pain (p=.005; r=−.270). The higher the age the lower the perception of the lowest pain in the first 24h.

When we relate sex with pain assessment we find significant differences only in the assessment of the highest pain. Women refer to more pain than men (Table 4).

Comparison of the perception of pain with different pain.

| Perception of greater pain | p | Perception of lesser pain | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 5.03±2.68 | .004 | 1.92±1.77 | .345 |

| Female | 6.47±2.57 | 2.47±2.35 | ||

| Education | ||||

| Primary | 5.94±2.93 | .781 | 2.65±2.16 | .256 |

| Secondary | 5.54±2.96 | 2.23±2.42 | ||

| Vocational training | 5.12±2.18 | 2.02±1.75 | ||

| University | 5.52±2.75 | 1.72±1.89 | ||

| 1st time surgery | ||||

| Yes | 5.86±2.11 | .887 | 2.93±2.62 | .208 |

| No | 5.56±2.80 | 2.02±1.92 | ||

| 1st time ICU | ||||

| Yes | 5.79±2.71 | .292 | 2.39±2.15 | .220 |

| No | 5.29±2.74 | 1.87±1.89 | ||

| Patient participation | ||||

| No | 5.31±3.04 | .505 | 1.85±2.11 | .706 |

| Light | 6.00±1.80 | 1.94±1.39 | ||

| High | 5.66±2.74 | 2.35±2.15 | ||

| Anxiety | ||||

| Little | 4.84±3.02 | .001 | 1.64±1.99 | .032 |

| Light | 5.85±2.03 | 2.52±1.56 | ||

| High | 7.35±1.98 | 2.85±2.56 | ||

| Helplessness | ||||

| Little | 4.61±2.85 | <.001 | 1.69±1.82 | .088 |

| Light | 6.04±2.11 | 2.46±1.88 | ||

| High | 7.44±1.85 | 2.60±2.33 | ||

| Non pharmacological methods | ||||

| Yes | 5.75±2.46 | .729 | 2.38±2.23 | .344 |

| No | 5.43±2.99 | 1.90±1.82 | ||

| Information on pain | ||||

| Yes | 5.49±2.76 | .771 | 2.40±2.19 | .104 |

| No | 5.79±2.67 | 1.63±1.58 | ||

| Pain 3 months prior to surgery | ||||

| Yes | 5.60±2.49 | .807 | 2.20±1.94 | .629 |

| No | 5.59±2.88 | 2.09±2.11 |

Pain referred to by the patient was not conditioned by their educational level nor by this being the first time they had surgery or were admitted to an ICU. This was not the case either for use of non pharmacological methods or information received. Participation in decision making with regards to pain treatment or the presence of pain of over 3 months onset prior to surgery did not impact the perception of pain (Table 4).

When we asked the patient if the pain made them feel anxious or defenceless we found that patients who stated the pain made them feel very anxious or defenceless were those who had the highest scores in the perception of greater pain, with statistically significant differences. Regarding the score for lower pain, there was an association with the feeling of anxiety and not with the feeling of helplessness (Table 4).

DiscussionThe highest pain score recorded was 4.47±2.75 and the lowest was .69±1.25 compared with 5.59±2.72 and 2.13±2.03 referred to by the patients. On comparing the recording with perception, there are statistically significant differences in both measurements. This fact coincides with that obtained in several research studies.14,15 Kemp et al.14 highlight that the professionals do not appropriate lyrecord pain due to the inappropriate use of the tools, either due to lack of knowledge, lack of time or because they perceive of complexity in the assessment. As has been commented upon, pain is multidimensional and includes subjective and objective variables31 and the professionals tend to attach greater importance to objective variables, such as haemodynamic changes for example.14 Although like Asgar17 indicates in his research on the relationship between pain and haemodynamic changes, the absence of significant changes does not mean that the patient does not feel pain.10,17

Furthermore, it is difficult for the patient to express the concept of pain in numbers.22,32 Kaptain et al.33 associate the level of intensity to the difficulty in distinguishing the different scores and to it being a novel experience. Also, the patients are under the effects of the anaesthesia or opiods and lack information regarding their treatment.33

The nurses should consider the value the patient assigns to his or her pain, even when this is incongruent with non verbal behaviour, with clinical data or the individual beliefs of the nurse.14,34 The important factors for an appropriate assessment include training, professional experience and length of time working in the unit since continuous experience in one area increases knowledge on how to care for a patient suffering from pain.34

In our study, the type of surgery conditioned the highest pain recorded. The highest score for chest or heart surgery, general surgery, urology and others is significantly higher than that of neurosurgery and vascular surgery. In patients who had undergone chest and heart surgery the scores on pain were the highest. The results are in keeping with that obtained by Kol et al.7 This may be due to the presence of chest draining tubes since, as Puntillo et al.8 stated, it is one of the most painful procedures in the ICU, according to patient assessment. Muscular incision and damage to intercostals nerves caused by chest surgery may also account for this finding.7 With regard to neurosurgery patients, several authors state that the perception exists that craniotomy is less painful than other procedures and that it is underestimated and inadequately treated.35,36 The recorded score could be justified by the difficulty in assessment owing to its characteristics.10,36 As previously commented upon, professionals attach greater importance to objective signs and in the case of neurosurgical patients, who usually present with a low level of consciousness, these signs suggest the patient is not suffering from pain.

Our results reflect that, the older the patient, the lower the perception of the lesser pain in the first 24h. In this sense Gibson and Farrell32 proposes there is a slight but demonstrable impairment related with age in early pain alert functions. There are no differences in the perception of greater pain. This result contrasts with that obtained by other authors,9,37,38 who found that older patients reflect lesser pain.

With regard to sex, our study showed that women give a higher score to greater pain, and this is also referred to by other authors.6,37,39,40 This is possibly due to the fact that hormone levels have a substantial impact on the perception of pain.39 In contrast, Moscoso y Bernal41 found that women refer to a lower intensity of pain compared to men in postoperative myocardial revascularisation and Navarro et al.9 found no statistically significant differences.

With regard to educational level, similarly to Navarro et al.,9 we found no association with pain perception.

Non pharmacological methods for the treatment of pain are interventions which may be carried out independently by nurses, in addition to medical treatment and in several studies they have been proven effective.5,42,43 However, in our study we found no statistically significant differences. In contrast to what was expected, patients who used non pharmacological methods did not perceive of higher pain.

The pain referred to by the patients was not conditioned by the information and decision making of the patient with respect to pain treatment. However, Hayes and Gordon44 indicate that informing patients about surgical pain preoperatively, together with treatment options and the support they will receive, leads to optimum subsequent pain management.

We found no association with the presence of pain of over 3 month onset prior to surgery, similarly to Puntillo et al.45 This result contrasts with that of other authors, who found there were differences in patients who previously referred to pain or were in treatment with analgesics.22,23,46 Diallo and Kautz22 highlighted that assessing what a patient does to relieve pain in their home and incorporating this treatment during their admittance to the ICU would improve the efficacy of the drugs used. In our unit, incorporating the measures which the patient employs in their own home to relieve the pain is a regular practice and justifies this result.

The patients who refer to pain making them feel very anxious or helpless were the ones who gave higher scores to pain. This fact differs from that obtained by Puntillo et al.,45 who did not find any statistically significant differences. Several authors9,41 state that anxiety is one of the most relevant problems in the surgical context and accept that the higher the anxiety the greater the pain. It is important to bear in mind that being admitted to an ICU causes the patient both physical and psychological stress. Gil et al.3 state that the patients staying in the ICU expressed they had stressful experiences that were related to pain. To improve this state of anxiety/defencelessness, the nurse plays an essential role. His or her continuous present, the tranquillity conveyed, the appropriate advice and information given could improve anxiety and pain.1,37

This study has methodological limitations. One of them is that the study was conducted in a single centre. Furthermore, when the patient requested it, a member of the research team assisted them in completing the questionnaire. This may have acted as a bias on the patient, who may not have felt free to express certain opinions. Another limitation is the fact that the analgesics used in pain treatment were not given a score by the patient, nor was the presence of invasive devices. Personal patient histories were not taken into account nor were the analgesics the patients had taken previously. These aspects could be addressed in future research studies.

ConclusionsThe patients in the ICU, referred to moderate pain during the first 24h.

The nurses underestimated the patient's pain referred to. Appropriate training could help to provide assessment strategies for better treatment.

Age, sex, anxiety and helplessness provoked by the pain were variables which conditioned the pain significantly. Knowing this information beforehand would lead to understanding and improving the perception of postoperative pain and thus customise and optimise treatment.

Conflict of interestsThe authors have no conflict of interests to declare.

Please cite this article as: López-Alfaro MP, Echarte-Nuin I, Fernández-Sangil P, Moyano-Berardo BM, Goñi-Viguria R. Percepción del dolor de los pacientes posquirúrgicos en una unidad de cuidados intensivos. Enferm Intensiva. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2018.12.001