Intensive Care Units are dynamic and complex units that require several professionals to work together. This is achieved through Interprofessional Collaborative Practice, which is the process in which different professionals interact with common goals and objectives in decision making, providing safe and quality care. Joint clinical sessions provide professionals with the opportunity to interact, improving communication and outcomes in clinical practice.

ObjectivesTo explore nurses' and physicians' perceptions of collaborative practice in joint clinical sessions in an Intensive Care Unit.

MethodologyA systematic literature review was conducted in the databases Medline, Pubmed, Cinahl, Web of Science and Psycinfo, including articles published in the last ten years.

ResultsThe analysis of the publications detected five main categories: (1) Concept: definition of interprofessional collaboration according to nurses and doctors, (2) Impact on clinical practice: value given to clinical sessions by nurses and doctors, (3) Barriers: relevant aspects in clinical sessions according to the perception of nurses and doctors, (4) Role: role perceived by each professional and (5) Improvement strategies: proposals put forward by nursing and medical professionals.

ConclusionsAlthough doctors and nurses are aware of the importance and impact of Interprofessional Collaborative Practice in the care of the critically ill patient, it is not a common practice in care.

Las Unidades de Cuidados Intensivos son unidades dinámicas y complejas que requieren del trabajo conjunto de varios profesionales. Esto se consigue mediante la Práctica Colaborativa Interprofesional, que es el proceso en el que interactúan diferentes profesionales con metas y objetivos comunes en la toma de decisiones, proporcionando una atención segura y de calidad. Las sesiones clínicas conjuntas brindan a los profesionales la posibilidad de interactuar, mejorando la comunicación y los resultados en la práctica clínica.

ObjetivosExplorar las percepciones de enfermeras y médicos sobre la práctica colaborativa en las sesiones clínicas conjuntas en una Unidad de Cuidados Intensivos.

MetodologíaSe realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura en las bases de datos Medline, Pubmed, Cinahl, Web of Science y Psycinfo, incluyendo artículos publicados en los últimos diez años.

ResultadosEl análisis de las publicaciones detectó cinco categorías principales: (1) Concepto: definición de colaboración interprofesional según enfermeras y médicos, (2) Repercusión en la práctica clínica: valor otorgado a las sesiones clínicas por enfermeras y médicos, (3) Barreras: aspectos influyentes en las sesiones clínicas según la percepción de enfermeras y médicos, (4) Rol: papel percibido por cada profesional y (5) Estrategias de mejora: propuestas planteadas por profesionales de enfermería y medicina.

ConclusionesA pesar de que médicos y enfermeras son conscientes de la importancia y repercusión de la Práctica Colaborativa Interprofesional en la atención al paciente crítico, no resulta una práctica habitual en la asistencia.

Intensive Care Units (ICUs) are considered highly complex due to the critical condition of the patient, the continuous interaction between professionals and family, and the need for rapid decision-making that leads to stressful situations. The care and attention of the critically ill patient therefore requires the efforts and coordinated work of a team of professionals.1,2

Interprofessional collaborative practice (ICP) is the process by which professionals from different disciplines meet to solve problems and participate in shared decision-making, thus providing comprehensive, safe and quality care to the patient and their family in all areas.1,3

In ICP, different factors converge that determine its success or failure, such as professional hierarchy; values and attitudes; professional roles; communication; respect; time and space where professionals carry out their activities; the use of technologies, and the delegation of functions.3,4

Collaborative work involves a series of elements that enable efficient and quality care, establishing clear shared goals, together with well-defined team roles and responsibilities. Group identity, a sense of belonging and empowerment are developed and democratic and leadership approaches are demonstrated, creating a space for communication, an essential element in care that facilitates the development of joint work practices.1,3,5

There are increasingly more studies that reflect the multiple benefits of ICP in improving quality and clinical safety: it increases patient satisfaction; decreases complaints; reduces costs and hospitalisation time; decreases mortality rate; complications, and clinical errors. PCI also improves organization, avoids duplication in actions and reduces stress and burnout of professionals, thus increasing their satisfaction and fostering their retention in institutions.3,5

Interdisciplinary clinical sessions are considered part of ICP6 and are of great importance, especially in environments such as ICUs. They are developed in daily meetings, aimed at the treatment and monitoring of the patient and are not a mere meeting point, but rather constitute a space for dialogue and the exchange of information in a learning environment, where each professional has the opportunity to contribute with their experience and knowledge.2

In interdisciplinary sessions, problems are identified and solutions are provided, establishing goals and objectives that enable the creation of a comprehensive care plan from a global patient viewpoint. This reduces variations in care and improves interprofessional communication, thereby facilitating the standardisation of care.2

When clinical sessions are not carried out effectively, errors may occur related to the transmission of information and treatments, as well as the occurrence of adverse events that have a direct and negative impact on the patient, so the use of this work approach is linked to the improvement in care and safety, through the fulfilment of goals through communication and collaboration between professionals.2,4

Evidence shows the relationship between interdisciplinary clinical sessions and improved clinical decision-making, confirming that ICP is a key element in achieving comprehensive and quality care for patients admitted to an ICU.6 Despite the multiple benefits of ICP, it is currently far removed from the ideal.3 Based on the above, there is a need to explore the perceptions of nurses and physicians regarding ICP in joint clinical sessions developed in an ICU, to identify the different roles they play, their impact on clinical practice and to propose improvement strategies.

ObjectivesGeneral objectives- 1

To explore nurses' and physicians' perceptions of collaborative practice in joint clinical sessions in an Intensive Care Unit.

- 1

To understand the meaning of professionals attach to collaborative practice.

- 2

To analyse the effect of interprofessional collaboration in joint clinical sessions in an ICU on clinical practice.

- 3

To identify the role of each professional (nurses and doctors) in collaborative clinical sessions.

- 4

To understand the improvement strategies that professionals propose from their perceptions.

To respond to the set of objectives, a PIS-type question was jointly formulated by the authors: What is the perception nurses and doctors have about interprofessional collaboration in clinical sessions in an ICU? The components were: P (population): nurses and doctors; I (intervention): interprofessional collaboration in joint clinical sessions in an Intensive Care Unit; S (outcomes): perception.

To answer this question, a systematic review of the literature was made in the Pubmed, Web of Science, Medline, Cinahl and Psycinfo databases, throughout the month of February 2023.

The keywords used were: perception, satisfaction, opinion, impact, implications, nurses, nursing, physicians, doctors, interprofessional collaboration, interdisciplinary communication, cooperative behaviour, multidisciplinary working, clinical sessions, ITU round, ICU round, ICU, intensive care unit, critical care, ITU. The MeSH terms used in the search were: nurses, perception, intensive care unit. These were used only in the Pubmed databases since their use in the others restricted the search. The Boolean operators used to define the search were ``AND'' and ``OR''. The strategy and algorithms used are specified below (see Fig. 1). The following search equations were used:

- -

Pubmed: (((((Perception [MeSH Terms]) OR (Perception OR Satisfaction OR Opinion OR Impact OR Implications)) AND (((Nurses[MeSH Terms]) OR (Nurses OR nursing)) OR (Physicians OR Doctors))) AND (Interprofessional collaboration OR interdisciplinary communication OR cooperative behaviour OR multidisciplinary working)) AND (Clinical sessions OR ITU round OR ICU round)) AND ((intensive care unit[MeSH Terms]) OR (ICU OR intensive care unit OR critical care OR ITU))

- -

Medline: ((((ALL = (Perception OR Satisfaction OR Opinion OR Impact OR Implications)) AND ALL = (Nurses OR nursing OR Physicians OR Doctors)) AND ALL = (Interprofessional collaboration OR interdisciplinary communication OR cooperative behaviour OR multidisciplinary working)) AND ALL = (Clinical sessions OR ITU round OR ICU round)) AND ALL = (ICU OR intensive care unit OR critical care OR ITU)

- -

Web of Science: (Perception OR Satisfaction OR Opinion OR Impact) OR (Implications OR Benefits) (All Fields) and (Nurses OR nursing OR nurs*) OR (Physicians OR Doctors) (All Fields) and Interprofessional collaboration OR interdisciplinary communication OR cooperative behaviour OR multidisciplinary working (All Fields) and Clinical sessions OR ITU round OR ICU round (All Fields) and ICU OR intensive care unit OR critical care OR ITU (All Fields) and 2022 or 2021 or 2020 or 2019 or 2018 or 2017 or 2016 or 2015 or 2014 or 2013 (Publication Years) and English or Spanish (Languages)

Articles that studied the perception of nurses and doctors, focused on joint clinical sessions and conducted in an ICU were included. Articles that addressed the perception of other professionals, patients or families, articles not focused on clinical sessions and those conducted in units other than an ICU were excluded (Table 1). The limits used to narrow the search were: articles published in the last 10 years, in English and Spanish.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|

| Aticles that include the perception of nurses and doctors. | Focusing on the perception of patients and families. |

| Articles focused on joint clinical sessions. | Articles that do not address interprofessional communication. |

| Studies foused on intensive care units (ICUs). |

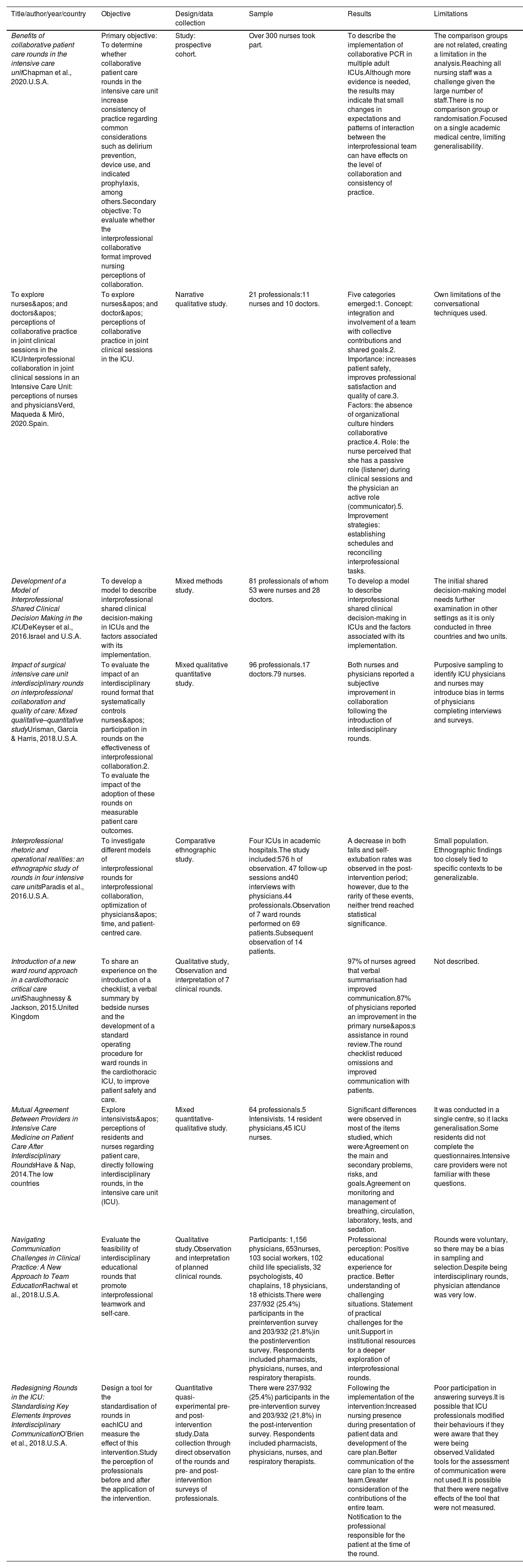

The selection of the articles was made by three reviewers in two consecutive phases. Independently at the beginning (in January 2023) and subsequently jointly (January-February 2023), aimed at minimising errors. Mendeley (Elsevier, Amsterdam, Netherlands) was used for bibliographic management. A total of 216 articles were obtained, leaving 161 when applying the limits. After reading the title and abstract, 36 remained, of which 11 were eliminated due to being duplicates. A thorough analysis of the articles was then carried out, of which 16 were excluded; four of them because they were not processed in an ICU, nine because they did not deal with the perception of nurses and doctors and three because they did not address interprofessional communication. No articles were obtained after snowballing. Finally, nine articles were included (Fig. 2 and Table 2).

Characteristics of the selected studies.

| Title/author/year/country | Objective | Design/data collection | Sample | Results | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Benefits of collaborative patient care rounds in the intensive care unitChapman et al., 2020.U.S.A. | Primary objective: To determine whether collaborative patient care rounds in the intensive care unit increase consistency of practice regarding common considerations such as delirium prevention, device use, and indicated prophylaxis, among others.Secondary objective: To evaluate whether the interprofessional collaborative format improved nursing perceptions of collaboration. | Study: prospective cohort. | Over 300 nurses took part. | To describe the implementation of collaborative PCR in multiple adult ICUs.Although more evidence is needed, the results may indicate that small changes in expectations and patterns of interaction between the interprofessional team can have effects on the level of collaboration and consistency of practice. | The comparison groups are not related, creating a limitation in the analysis.Reaching all nursing staff was a challenge given the large number of staff.There is no comparison group or randomisation.Focused on a single academic medical centre, limiting generalisability. |

| To explore nurses' and doctors' perceptions of collaborative practice in joint clinical sessions in the ICUInterprofessional collaboration in joint clinical sessions in an Intensive Care Unit: perceptions of nurses and physiciansVerd, Maqueda & Miró, 2020.Spain. | To explore nurses' and doctor' perceptions of collaborative practice in joint clinical sessions in the ICU. | Narrative qualitative study. | 21 professionals:11 nurses and 10 doctors. | Five categories emerged:1. Concept: integration and involvement of a team with collective contributions and shared goals.2. Importance: increases patient safety, improves professional satisfaction and quality of care.3. Factors: the absence of organizational culture hinders collaborative practice.4. Role: the nurse perceived that she has a passive role (listener) during clinical sessions and the physician an active role (communicator).5. Improvement strategies: establishing schedules and reconciling interprofessional tasks. | Own limitations of the conversational techniques used. |

| Development of a Model of Interprofessional Shared Clinical Decision Making in the ICUDeKeyser et al., 2016.Israel and U.S.A. | To develop a model to describe interprofessional shared clinical decision-making in ICUs and the factors associated with its implementation. | Mixed methods study. | 81 professionals of whom 53 were nurses and 28 doctors. | To develop a model to describe interprofessional shared clinical decision-making in ICUs and the factors associated with its implementation. | The initial shared decision-making model needs further examination in other settings as it is only conducted in three countries and two units. |

| Impact of surgical intensive care unit interdisciplinary rounds on interprofessional collaboration and quality of care: Mixed qualitative–quantitative studyUrisman, García & Harris, 2018.U.S.A. | To evaluate the impact of an interdisciplinary round format that systematically controls nurses' participation in rounds on the effectiveness of interprofessional collaboration.2. To evaluate the impact of the adoption of these rounds on measurable patient care outcomes. | Mixed qualitative quantitative study. | 96 professionals.17 doctors.79 nurses. | Both nurses and physicians reported a subjective improvement in collaboration following the introduction of interdisciplinary rounds. | Purposive sampling to identify ICU physicians and nurses may introduce bias in terms of physicians completing interviews and surveys. |

| Interprofessional rhetoric and operational realities: an ethnographic study of rounds in four intensive care unitsParadis et al., 2016.U.S.A. | To investigate different models of interprofessional rounds for interprofessional collaboration, optimization of physicians' time, and patient-centred care. | Comparative ethnographic study. | Four ICUs in academic hospitals.The study included:576 h of observation. 47 follow-up sessions and40 interviews with physicians.44 professionals.Observation of 7 ward rounds performed on 69 patients.Subsequent observation of 14 patients. | A decrease in both falls and self-extubation rates was observed in the post-intervention period; however, due to the rarity of these events, neither trend reached statistical significance. | Small population. Ethnographic findings too closely tied to specific contexts to be generalizable. |

| Introduction of a new ward round approach in a cardiothoracic critical care unitShaughnessy & Jackson, 2015.United Kingdom | To share an experience on the introduction of a checklist, a verbal summary by bedside nurses and the development of a standard operating procedure for ward rounds in the cardiothoracic ICU, to improve patient safety and care. | Qualitative study, Observation and interpretation of 7 clinical rounds. | 97% of nurses agreed that verbal summarisation had improved communication.87% of physicians reported an improvement in the primary nurse's assistance in round review.The round checklist reduced omissions and improved communication with patients. | Not described. | |

| Mutual Agreement Between Providers in Intensive Care Medicine on Patient Care After Interdisciplinary RoundsHave & Nap, 2014.The low countries | Explore intensivists' perceptions of residents and nurses regarding patient care, directly following interdisciplinary rounds, in the intensive care unit (ICU). | Mixed quantitative-qualitative study. | 64 professionals.5 Intensivists. 14 resident physicians,45 ICU nurses. | Significant differences were observed in most of the items studied, which were:Agreement on the main and secondary problems, risks, and goals.Agreement on monitoring and management of breathing, circulation, laboratory, tests, and sedation. | It was conducted in a single centre, so it lacks generalisation.Some residents did not complete the questionnaires.Intensive care providers were not familiar with these questions. |

| Navigating Communication Challenges in Clinical Practice: A New Approach to Team EducationRachwal et al., 2018.U.S.A. | Evaluate the feasibility of interdisciplinary educational rounds that promote interprofessional teamwork and self-care. | Qualitative study.Observation and interpretation of planned clinical rounds. | Participants: 1,156 physicians, 653nurses, 103 social workers, 102 child life specialists, 32 psychologists, 40 chaplains, 18 physicians, 18 ethicists.There were 237/932 (25.4%) participants in the preintervention survey and 203/932 (21.8%)in the postintervention survey. Respondents included pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists. | Professional perception: Positive educational experience for practice. Better understanding of challenging situations. Statement of practical challenges for the unit.Support in institutional resources for a deeper exploration of interprofessional rounds. | Rounds were voluntary, so there may be a bias in sampling and selection.Despite being interdisciplinary rounds, physician attendance was very low. |

| Redesigning Rounds in the ICU: Standardising Key Elements Improves Interdisciplinary CommunicationO’Brien et al., 2018.U.S.A. | Design a tool for the standardisation of rounds in eachICU and measure the effect of this intervention.Study the perception of professionals before and after the application of the intervention. | Quantitative quasi-experimental pre- and post-intervention study.Data collection through direct observation of the rounds and pre- and post-intervention surveys of professionals. | There were 237/932 (25.4%) participants in the pre-intervention survey and 203/932 (21.8%) in the post-intervention survey. Respondents included pharmacists, physicians, nurses, and respiratory therapists. | Following the implementation of the intervention:Increased nursing presence during presentation of patient data and development of the care plan.Better communication of the care plan to the entire team.Greater consideration of the contributions of the entire team. Notification to the professional responsible for the patient at the time of the round. | Poor participation in answering surveys.It is possible that ICU professionals modified their behaviours if they were aware that they were being observed.Validated tools for the assessment of communication were not used.It is possible that there were negative effects of the tool that were not measured. |

To analyse the methodological quality, the CASPe7 critical reading tools were used for qualitative articles, and Joanna Briggs8 for quasi-experimental and cohort studies. In general, the score was high (Table 3).

Methodological quality of the selected studies.

| Article | Strong points | Weak points |

|---|---|---|

| Benefits of collaborative patient care rounds in the intensive care unitChapman et al., 2020. U.S.A. | Clear and structured summary.Objectives well described.The implementation of rounds was measured in a valid and reliable manner.Follow-up time was reported.The ethical considerations addressed in the study were detailed. The results were measured in a valid and reliable manner. | Lacks randomisation.Focusing on a single academic medical centre restricts generalisability of results. No confounders were identified.No strategies were used to address incomplete follow-up.JBI: 7/11 |

| Interprofessional collaboration in joint clinical sessions in an Intensive Care Unit: perceptions of nurses and physicians. Verd, Maqueda & Miró, 2020. Spain. | Clear and structured summary.Precise objectives.Well-detailed study methodology, including type of study, sample and its selection and development.Precise results, described in categories.Describes the methods of evaluation of the results. Reflects the implications and limitations of the study. Describes the ethical considerations of the study.CASPe: 10/10 | Not presented. |

| Impact of surgical intensive care unit interdisciplinary rounds on interprofessional collaboration and quality of care: Mixed qualitative– quantitative studyUrisman, García & Harris, 2018. U.S.A. | Precise objectives. Type of study and defined objectives. Complete and precise statistical analysis. Well-defined results.Measures are taken to avoid possible biases. Limitations of the study are outlined.Ethical aspects are taken into account.CASPe: 8/10 | Training of study performers not specified. |

| Interprofessional rhetoric and operational realities: an ethnographic study of rounds in four intensive care unitsParadis et al., 2016. U.S.A. | Comparative ethnographic study. Long-term evaluation of the study phenomenon (12 months).Detailed statement of limitations.Detailed contextualization of the study. Approval by the ethics committee.Detailed data collection process.CASPe: 9/10 | Unclear, unstructured abstract. Does not specify the training of the people who conducted the study. Small sample size (4ICUs). |

| Introduction of a new ward round approach in a cardiothoracic critical care unitShaughnessy & Jackson, 2015. United Kingdom. | Objectives defined.Ethical aspects are taken into account.The results were classified into categories to facilitate their description.The data collection technique is clearly specified. The implication of the study in clinical practice is outlined.CASPe: 7/10 | The type of study is not defined.The number of participants in the study, or their profession, is not clear.The limitations of the study are not raised. |

| Development of a Model of Interprofessional Shared Clinical Decision Making in the ICUDeKeyser et al., 2016. Israel and U.S.A. | Clearly defined objectives.The methodology used is consistent.Rigorous data analysis. Clear presentation of results.Ethical aspects are taken into account.The data collection methods used are appropriate for the research question.CASPe: 8/10 | Biases defined.No study limitations defined. |

| Mutual Agreement Between Providers in Intensive Care Medicine on Patient Care After Interdisciplinary RoundsHave & Nap, 2014. The low countries. | Internal consistency of the survey used validated with a Cronbach's alpha of 0.78.Rigorous data analysis. Objective clearly stated. Inclusion of explanatory figures.Specifies the need for future studies to be able to generalize the results obtained.CASPe: 9/10 | Lack of generalizability: study conducted in a single center. No ethical issues specified. No limitations specified. |

| Navigating Communication Challenges in Clinical Practice: A New Approach to Team EducationRachwal et al., 2018. U.S.A. | Structured and clear summary.Long-term monitoring of the phenomenon to be studied (6 years). Large sample size (1,156 health workers).Precise results, described in categories. Includes future implications.Inclusion of limitations. Very detailed conclusion.CASPe: 8/10 | Possible bias in sampling due to voluntary participation. Does not specify who is conducting the research.Ethical considerations are not clearly described. |

| Redesigning Rounds in the ICU: Standardizing Key Elements Improves Interdisciplinary CommunicationO’Brien et al., 2018. U.S.A. | Clear and structured summary.Detailed explanation of the phenomenon under study.Use of the PDCA method to carry out the intervention. Detailed data collection process.Inclusion of explanatory graphs. Limitations clearly stated. Suggests new research. | Tools used not validated. The ethical considerations were not clearly described.JBI: 8/9 |

There was no need for an ethical committee since no patients were involved in the study. No funding was received for this study.

ResultsAfter reading and analysing the selected literature, the results obtained were grouped into five categories: concept, impact on clinical practice, role, barriers, and improvement strategies. The categorisation was based on the integrative synthesis model proposed by Dixon et al.9, through which the categories were established by data interpretation using generalisability and causality techniques. Specifically, the thematic analysis model was used, which consisted of identifying the most recurrent themes in the analysed literature and summarising the conclusions under thematic headings.9

Definition of interprofesional collaboration according to nurses and doctors: conceptCollaborative practice and interprofessional relations in the workplace are considered by both professionals as decisive aspects. Interprofessional collaboration is described by nurses and doctors as the assumption of a series of competences and responsibilities by each discipline, as well as the interdependence and democracy between the members of both professions.10 Nurses added to the definition the realisation of individual and joint contributions with the common objective of reaching shared clinical criteria and being able to offer higher quality patient care.

Furthermore, doctors emphasised the consensual process for shared decision-making, which they considered the supporting basis of interprofessional collaboration.10 They also agreed on the ultimate purpose of interprofessional collaboration and, therefore, of clinical sessions as the creation of an environment in which to share information, problems, treatment and evaluation plans, to achieve a more precise adjustment to patient needs.11,12

Value given to the clinical sessions by nurses and doctors: impact on clinical practiceInterdisciplinary clinical sessions are considered essential for various reasons: firstly, professionals agree on the positive impact on patient care, the literature emphasises the decrease in mortality and morbidity, hospitalisation time and increased satisfaction of patients and professionals.12–14

This clinical practice means that problems and objectives by each member of the team can be verbalised, which facilitates the unification and a better understanding of the proposed care plan, together with the approach to sensitive issues that could not otherwise be covered.1,15 Likewise, it is related to early recognition of adverse events, promotion of a teamwork culture, improvement in interprofessional communication and retention of nurses in ICUs.16

Impacting aspects in clinical sessions according to the perception of nurses and doctors: barriersSometimes, clinical sessions in ICUs are affected by several factors that hinder their development. On the one hand, there are individual factors such as experience, personality, knowledge and availability that directly condition interdisciplinary sessions.14 On the other, there are relational factors such as the ability to listen to, trust and respect other professionals. ICU nurses and doctors admit to only carrying out the orders of colleagues they trust. However, if they consider that the professional issuing the order is not trustworthy, they need to confirm this with someone they do consider trustworthy.14

Finally, there are factors at the system level, such as the excessive workload of nurses, stressful working conditions, continuity of care, use of technology and the architectural environment. Doctors report that the role of nurses is essential in morning rounds. However, they report not being able to attend on many occasions due to workload.14

Role perceived by each professional: part playedThe most recent literature highlights the dominance of doctors in decision-making compared to nurses.17

Although nurses currently perceive that there is not as much hierarchy as before12 with respect to doctors, they continue to feel that they adopt a passive role and that their participation is only occasional, despite being the professionals with the greatest patient knowledge.10 Sometimes they feel both verbally and physically marginalised, left in the background, since they generally do not even have a space to sit in at the session. This explains why the nursing team is sometimes reluctant to contribute to these clinical sessions.18 However, doctors perceive that they play an active role, and they sometimes invite nurses to participate, since they are the ones who have a withdrawn attitude and lack involvement.10 They highlight nurses as a crucial part of clinical sessions because they possess the information they need in order for the best decisions to be made. However, some of them consider hierarchy as essential to this practice,14 undermining nurses by regarding them as mere executors of doctors.10 Both professionals agree on the leadership of physicians in ICP and the lack of consensus in decision-making, with the prevalence of medical treatment over nursing care.10

Improvement strategies proposed by nurses and doctorsSeveral proposals were put forward by nurses and doctors to encourage the participation of nurses in the sessions.10 Firstly, doctor on-duty doctor could establish the predetermined order of the session to facilitate the individual planning of each profesional.16 They also referred to an interest in implementing a mandatory interlude in all sessions during which nurses could provide information. They mentioned the need to briefly summarise the action plan at the end of each multidisciplinary round to avoid confusion among professionals,16 and as a last measure, the implementation of a safety checklist to guarantee coverage of the most important elements to be addressed.18

DiscussionThe results of this research expand the knowledge regarding professionals’ perception on interprofessional collaboration in clinical sessions in an ICU, but also reveal its impact and possible improvement strategies.

According to Miró,3 doctors understand ICP as the process through which they make decisions in a unidirectional manner and, despite respecting the nursing discipline, they are the ones who advise them in the exercise of their interventions with patients. In contrast, in our results, doctors highlight the importance of a consensual process for shared decision-making, in which they consider interprofessional collaboration to be a key foundation.

However, the perception of nurses was similar to that described. Nurses emphasized the lack of recognition of their contributions by doctors in shared decision-making3 Although our results described an improvement in the hierarchy in clinical sessions, nurses still contributed little, despite being the ones who know the patient best.

ICP has a strong impact on clinical practice. Miró3 reinforces this idea by listing different positive elements that occur when working collaboratively, since it enables clear goals and roles to be established in the care of the patient and family, develops a group identity that empowers the different members of the team, and fosters feelings of belonging, cohesion and trust. This group work culture favours interdependence between the different professionals in the unit through a democratic approach and shared leadership. It also helps to develop updated protocols thanks to the various interdisciplinary approaches. There are also other authors who support this theory, since it has been seen that numerous studies have supported an improvement in patient outcomes thanks to good interdisciplinary collaboration between doctors and nurses.19 Despite this, Del Barrio5 reflects in his study that nurses have a greater attitude towards collaboration and teamwork in relation to doctors, an attitude that can be justified by the fact that the latter consider themselves the leaders of the team and that the purpose of the team is to help them achieve the objectives in the treatment of the patient.

Miró3 states that ICP can generate a positive impact by increasing patient satisfaction, reducing the length of clinical stays and avoiding duplication of efforts. These repercussions have been seen in our results, since clinical sessions are able to adjust more precisely to the needs of the patient, facilitate unification and improve understanding of the care plan.

Amaral et al.,20 reaffirms the importance of clinical sessions in ICUs due to the complexity of critical patients. Their development allows for the safe development of care plans, efficiently integrating the opinion of the different members of the team. Our results propose improvement strategies, such as a mandatory pause for the contribution of nurses, which promotes an action plan for better patient care and avoids possible confusion between professionals.

However, Amorós21 states that, despite the objective relevance of interdisciplinary clinical sessions in increasing the safety and quality of healthcare, healthcare environments are difficult. There continue to be hierarchical relationships and dominance by doctors that hinder the development of a real collaborative practice.

There is a predominance of studies that indicate a lack of research to find tools that facilitate the implementation of ICP in healthcare units.21 Some studies, such as that of Manojlovich et al.,22 developed tools and procedures to measure communication between nurses and doctors in ICUs and evaluate the possible components involved in communication and thus identify the weak points to establish an action plan to optimise ICP. Furthermore, the study by Soto-Fuentes et al.19 reports that interprofessional education in health should start at the beginning of one’s career, both in medicine and nursing, since it is an experimental learning that promotes the understanding of roles and the importance of working together to provide safe and quality care to the patient.

ConclusionsBoth nurses and doctors are aware of the relevance, impact and benefits of implementing collaborative practice in joint clinical sessions in an ICU, but, despite this, both professionals have different perceptions about it, which makes its implementation difficult.

Nurses perceive an improvement in communication and relationships with doctors, but despite this, they continue to adopt a passive role in their contribution to joint clinical sessions, which raises the need for empowerment and active participation, while doctors recognise their dominance, although they emphasize the role of nurses in patient knowledge.

A structured clinical session format, with defined schedules, would increase the participation of nurses, contributing to the improvement of patient safety and care, facilitating communication and the implementation of a comprehensive care plan.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.