Edited by: Mónica Vázquez. Clínica Universidad de Navarra, Spain

Last update: February 2025

More infoThe intensive care units structure, the technological improvement and the severity of the patients, require that there be harmony between all the actors involved in assisting the critically ill patient. Added to this context is that the current role of the supervisor involves assuming more and more management skills, without losing sight of the need to frame professional practice within the framework of a philosophy of care. Given this challenge for the supervisor, the appearance in our environment of the Advance Practice Nurse figure (APN) is an opportunity. The APN is essential to improving patient care, staff development and the implementation of evidence-based practice.

This article describes how the APN works with the different members of the health team and what the results have been since their incorporation.

The APN leads efforts to maintain quality of care. They use their knowledge to assess gaps in practice and between practice settings, and to design and lead evidence-based practice changes so that benchmarks can be met in the most efficient and timely manner. Additionally, it supports the organization to respond to a constantly changing healthcare environment and is instrumental in achieving its goals.

La estructura de las Unidades de Cuidados intensivos, el perfeccionamiento tecnológico y la gravedad de los pacientes, exigen que exista armonía entre todos los actores participantes del asistir al paciente crítico. A este contexto se añade que el rol actual de la supervisora pasa por asumir cada vez más competencias en gestión, sin perder de vista la necesidad de enmarcar la práctica profesional en el marco de una filosofía de cuidados. Ante este reto para la supervisora, la aparición en nuestro entorno de la figura de la Enfermera de Práctica Avanzada (EPA) es una oportunidad. La EPA es fundamental para mejorar la atención al paciente, el desarrollo del personal y la implantación de la práctica basada en la evidencia.

En este artículo se describe cómo trabaja la EPA con los diferentes miembros del equipo de salud y cuáles han sido los resultados desde su incorporación.

La EPA lidera los esfuerzos para mantener la calidad del cuidado. Utiliza su conocimiento para evaluar las brechas dentro de la práctica y entre los entornos de práctica, y diseñar y liderar cambios en la práctica basados en la evidencia para que los puntos de referencia puedan cumplirse de la manera más eficiente y oportuna. Además, apoya a la organización para responder a un entorno sanitario en constante cambio y es un instrumento para alcanzar sus metas.

The Intensive Care Unit (ICU) is a structured unit that provides specialist care to critically ill, life-threatened patients, using increasingly advanced technologies to try to preserve the life of the critically ill patient, requiring highly trained healthcare professionals.1

Technological improvements are gradually changing the operational dynamics of the ICU. As a consequence of this change, there is a need to make decisions about death and dying and about the stay of critically ill patients in these units. This has led to the realisation of the importance of harmony between the professionals working in the ICU, the patients admitted to the ICU and their families. It is therefore necessary to improve the care of all those involved in the care of the critically ill patient.2 It should be added that the current role of the supervisor is to take on more and more management skills (planning, organising, communicating, directing, evaluating, and promoting of quality), without losing sight of the need to frame professional practice within a philosophy of care.3 Given this challenge for supervisors, the emergence of the advanced practice nurse (APN) in our setting is an opportunity4 to improve patient care, for staff development, and to implement evidence-based practice.5

The International Council of Nurses (ICN) defines the APN as "a generalist or specialised nurse who has acquired, through additional graduate education (minimum of a master’s degree), the expert knowledge base, complex decision-making skills and clinical competencies for Advanced Nursing Practice, the characteristics of which are shaped by the context in which they are credentialed to practice".6 The Clinical Nurse Specialist (CNS) and the Nurse Practitioner (NP) are the two most common types of APN internationally. According to the ICN, the CNS is an APN "who provides expert clinical advice and care based on established diagnoses in specialised clinical fields of practice along with a systems approach in practicing as a member of the healthcare team".6 They combine expertise in patient care with professional leadership through education, expert advice, and research. Research skills refer to systematic work to address questions arising from practice. This includes the interpretation and use of evidence in clinical practice and the evaluation of evidence to improve quality. It also involves active participation in studies that generate knowledge.7,8 Transformational leadership is key to leading change and empowering others to influence clinical practice.7,8

The role of the CNS was incorporated into the Critical Care Unit of the Clínica Universidad de Navarra in 2012. For this purpose, the conceptual model PEPPA (patient-centred, evidence-based, participatory process for the advanced practice nurse) was used. This model, proposed by Bryant Lukosius & Di Censo in 2004,9 provides a systemic and evidence-based approach to the development of the advanced practice role based on the needs of the patient; it guides the development of advanced practice in a holistic way that focuses on patient care; it promotes the use of knowledge, skills, and expertise in each of the competencies of the APN; it creates an optimal professional environment for the development of the advanced practice role; and because it allows for continuous and rigorous evaluation of the advanced practice role based on the results obtained with the new care plan.

Thus, incorporation of the role of the advanced practice nurse in the ICU has led to the definition of competences that, in this case, the supervisor and the APN will develop in order to strengthen both the area of management and the area of support and development of practice. The supervisor focuses on everything related to the management of human and material resources, the promotion of quality, preparation of the environment to achieve the proposed objectives, and evaluation of the professional. The APN develops direct clinical practice, consultation, collaboration, coaching, and research. The supervisor and APN, although they have different roles, share competences, so that communication and collaboration between the two in clinical care is key to achieving the goals of patient and family care.

Within the ICU, the APN uses their core competences to engage and collaborate with all members of the team (doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, pharmacists, etc.). These collaborative efforts enhance patient experience and improve resource utilisation and outcomes. The APN uses advanced knowledge, clinical research, change management, and critical thinking to improve nursing practice and teamwork, which impacts on the clinical management of the critically ill patient.10

This article describes how the APN works with the different members of the healthcare team and what the outcomes have been since its introduction.

How does the APN work?Setting objectivesEach year, based on the institution's own objectives, an analysis of the unit's situation and taking into account the projects launched by the Spanish Ministry of Health in relation to the ICU, the APN, together with the supervisor, sets the unit's work objectives.

One of the objectives that they work towards as part of their professional leadership is to implement evidence-based practice within a culture of safety. To achieve this, work is undertaken to review and adopt existing protocols and to develop and implement new protocols in response to emerging needs or areas for improvement identified in practice.

Based on Spanish Ministry of Health objectives (maintaining indicators for ventilator-associated pneumonia or preventing central venous catheter-associated bacteraemia) and aligned with an institutional objective (maintaining a culture of safety), care protocols are reviewed and updated. As the indicators are held to a standard, the APN improves the safety culture by shifting the focus of care from an outcome-based model to a process-based model. If the focus is on outcomes alone, outcomes will not continue to be good. Therefore, different aspects of safety are worked on each year. First, the protocols to be worked on are identified, a literature review is undertaken, and the protocol is updated, if necessary, then compliance with these protocols and their documentation is audited in the computer record. Outcomes are evaluated and areas for improvement are identified; training is provided, and the necessary changes are implemented; and finally, the outcomes are measured again. The whole process involves the entire nursing team.

One of the objectives of the institutional work is to introduce a family approach to care. To this end, the APN, together with other APNs in the institution and with the help of expert researchers from the university, is participating in a project aimed at training nurses in the implementation of this systems approach to care.

Finally, objectives derived from the unit itself are defined following an audit carried out by the supervisor and direct observation of the APN in daily practice. Areas for improvement in care are identified and/or risk factors derived from admission to the ICU (thromboembolic prophylaxis, early rehabilitation, safe transfer) are addressed. The APN is also responsible for the training of professionals. To this end, they coordinate and teach the master's degree in "Formación Permanente en Cuidados Especializados de Enfermería en Cuidados Intensivos" (continuous training in specialist ICU nursing care, which is compulsory post-graduate training to work in the ICU) and organises training for the ICU staff. Each year, they also set up a working group to carry out a research study on areas for improvement identified in practice.

How do they work with the supervisor?There is direct collaboration with the unit supervisor. This relationship is based on their complementary roles. As noted above, the nurse supervisor is the nurse manager closest to the point of care. According to Williams et al.,11 supervisors are nurses with extensive practical experience who perform work beyond direct clinical practice. In particular, supervisors facilitate rather than provide care because they spend much more time on activities related to management and staff development and training than on direct patient care or research. Specifically, the audits that take place in the ICU are carried out by the supervisor who, together with quality, sets part of the unit's safety objectives. These objectives are then discussed with the EPA and together they draw up an action plan to improve quality and safety in the areas identified by the audit.

This complementarity is reflected in daily work, where in order to achieve the annual objectives, the supervisor evaluates each of the ICU nurses through a portfolio that they have been working on daily, and at the bedside the APN works on these objectives with each of the nurses. In addition, this participative observation by the APN and the evaluation of the portfolios by the supervisor, establishes continuous training, aligned with the annual objectives of the ICU.

One aspect that deserves special consideration and that has a great impact on the achievement of objectives is the weekly evaluation meeting carried out jointly by the APN and the supervisor. The achievements, shortcomings, points for improvement, strengths, and what to do and how to work the following week are presented at these meetings. This shows how the implementation of each change is adapted to the needs or situations detected throughout the implementation. For example, in the prevention of urinary tract infections, in delivering care to the patient it was observed that their catheter was not secured, yet it always appeared as secured in the computer record. It is well known that this care is important for the prevention of urinary tract infections. During the meeting, an attempt was made to understand the barriers and facilitators to securing the catheter. Thus, following this study resulting from discussions with the nursing team, and with the supervisor, it was decided that using a specific urinary catheter fixation device would facilitate delivering this care. After piloting this care, and in subsequent conversations with the nursing team, this was considered feasible and appropriate, and was implemented on a permanent basis.

How do they work with nurses?The APN works primarily in direct clinical practice with the individual ICU nurses in the daily care of inpatients. Thus, they accompany and train them, ensuring, in turn, holistic care and continuity of care for patients. They also play a central role in complex patient and family situations detected by any member of the ICU team.

Like the supervisor, the APN reviews the objectives set for the unit on a daily basis. For example, in the case of central line-associated bacteraemia prevention, staff undergo accredited online training. At the bedside, the APN checks that the various aspects of the bacteraemia project have been implemented (scheduling of drip changes according to the unit's protocol; presence of a free lumen for administering medication boluses to avoid unnecessary drip interruptions; no interrupted drips; daily checking that the patient needs all the venous catheters that have been inserted). All this is also recorded in the computer programme.

This monitoring is closer with more novice nurses, however, with coaching and advice in every situation. For example, when they start working in the unit, the APN accompanies them through each of the phases of assessment, planning, and delivery of care. They work on how and what is communicated in the report and how the patient is assessed. From this phase, they draw up the care plan and then deliver it under supervision. As these nurses become more competent, the intensity of this coaching decreases.

This accompaniment in the development of direct clinical practice, as well as the coaching and consultation work of the APN, aims to enhance nurses’ autonomy. This is done by seeking, clarifying, and defining what each nurse wants to achieve, stimulating self-discovery, eliciting solutions, and encouraging the creation of strategies by the nurse themself.

Another objective of the APN is to promote collaboration and cohesion within the nursing team. In this way, the more experienced nurses also contribute to the practical training of more novice nurses. For example, if they have a complicated patient and have performed any of their care, the expert nurse will accompany them.

How do they work with the medical team?The APN works together with the medical team. Thus, they propose improvements in the care of the patient. An example of this joint and complementary work is the development of a joint information protocol for families. This protocol arose from a study carried out with the families of the unit where it was detected that as the patient became more chronic, the information they received was poorer and they demanded information from both the doctors and the nurses. We spoke with the medical team and proposed designing a protocol to give information to the nurse and the doctor together every day, at a specific time, in a suitable place.12

It should be noted that the supervisor, the unit's medical manager, and the APN meet weekly to identify areas for improvement and propose solutions to the demands of the unit.

How do they work with other departments?The ICU APN works not only with the key players in the unit, but also with other departments that are committed to continuous improvement of care. For example, they have worked with the Preventive Nursing Department to develop a protocol for cleaning cubicles on discharge and to prevent cross-infection. With the rehabilitation department, they have developed a specific mobilisation protocol for critical patients.13 With the ENT department, they have developed a protocol for early decannulation of tracheotomised patients. And they have worked with the pain APN on pain management in post-operative patients in the ICU.

How do they work with the institution?As mentioned above, the APN not only plays an advanced role in critical care, but also collaborates with various aspects of the hospital. For example, the APN is a member of the Clinical Practice Committee, which aims to promote nursing excellence throughout the institution. This committee addresses issues related to clinical practice (development, improvement, innovation, evaluation) through the expansion of knowledge and the use of evidence-based practice and the improvement of nurses' performance. For example, they have worked on improving the assessment of pain in patients in the immediate post-operative period and in chronic patients, deterioration of mobility, the patient discharge report, etc. In the case of pain, for example, a study was carried out on all post-operative patients in the hospital to assess their perception and how it affected their activities. In addition, the use of assessment scales was defined for different patients, whether they have cognitive impairments, paediatric patients, or those with communication difficulties. And thanks to this work, pain assessment in the immediate post-operative period, in paediatric patients and in patients with cognitive impairment has been improved.

Another key function of the APN is the development and review of all clinical practice procedures (oxygen therapy, partial immobilisation protocol, action in the case of a patient with massive haemorrhage, etc.), with the aim of reducing variability in care throughout the care process, including the interdisciplinary team.

Finally, the APN is also a member of various hospital working groups and committees. For example, in the pressure ulcer (PU) working group, they have been involved in updating the PU prevention and treatment guideline according to scientific evidence, implementing evidence-based practice and identifying improvement actions.

What were the outcomes?Maintaining quality indicatorsAs described above, the APN leads the efforts to prevent central venous catheter-associated bacteraemia, catheter-related urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia, among others.5,10

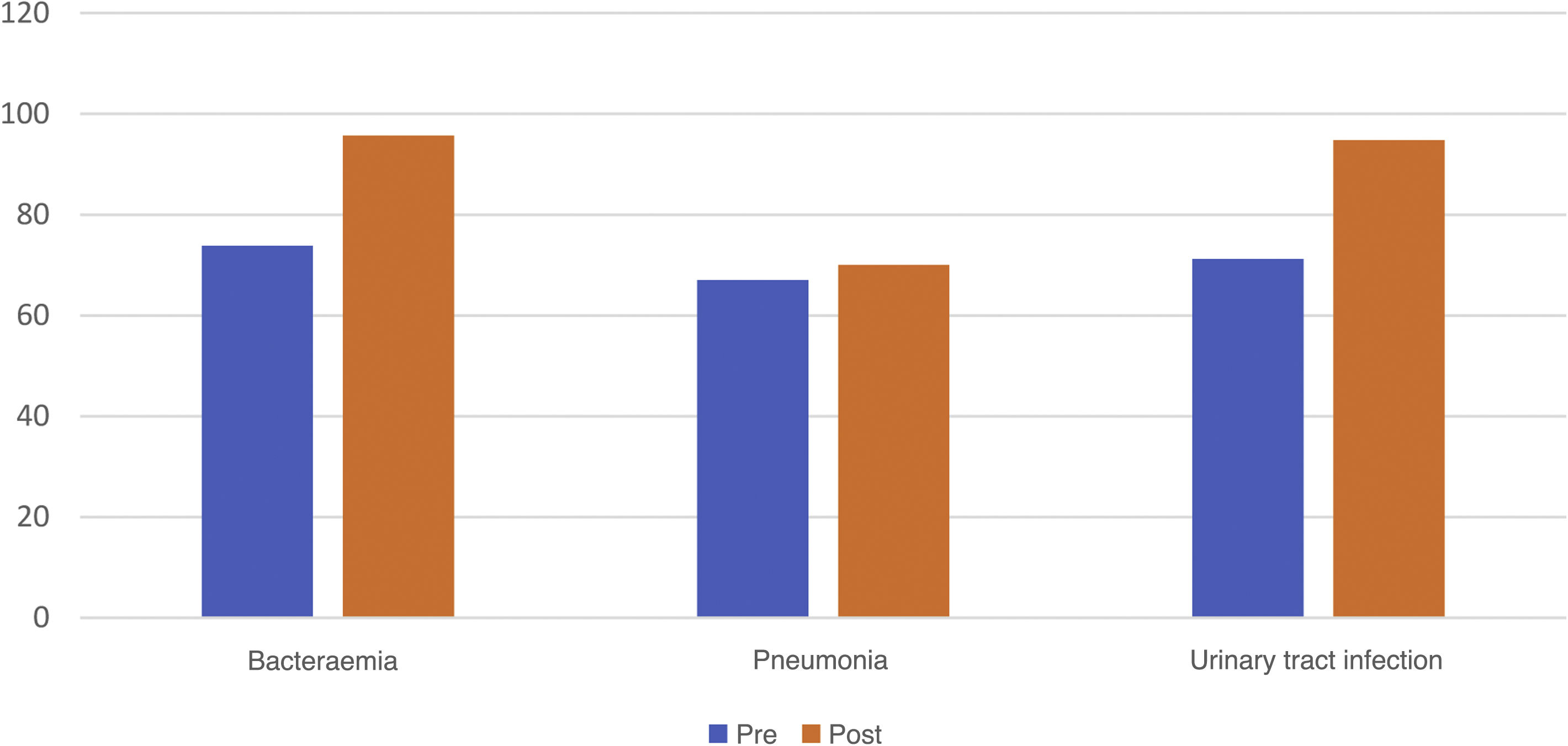

In the first year in which the APN was incorporated into the team, a study was conducted to measure the degree of compliance with the measures for preventing central venous catheter-associated bacteraemia, catheter-related urinary tract infections, ventilator-associated pneumonia. Fig. 1 shows the improvement in the degree of compliance with prevention measures after individualised training sessions and daily practice monitoring (early detection and correction).

Training and monitoring in practice helps maintain bacteraemia and pneumonia indicators at the quality standard. In the last year, central venous catheter-associated bacteraemia was .72 per 1,000 patients/day of short-duration central venous catheters, improving on the target, which is 1.2. In relation to ventilator-associated pneumonia, the indicator is 2.65 compared to the target of 6.22 per 1,000 patients/day. The indicator for catheter-related urinary tract infections is also positive, 2.2 compared to the standard of 2.74.

Evidence-based practice implementation/research findingsThe APN also uses their knowledge to assess gaps within and across practice settings and to design and lead evidence-based changes to achieve benchmarks in the most efficient and timely way.5 To this end, the APN has set up a working group to identify protocols to work on. The criteria for selecting these protocols are determined by the objectives of the institution and the objectives of the unit. Once the protocols have been identified, each member of the group selects those they wish to work on according to their area of interest. Each protocol is worked on by 2 or 3 people. A literature review is conducted, updated, and presented to the nursing team in a training session.

The APN also conducts studies to investigate and measure changes in priority areas of care. For example, a study was conducted in 2013, one of the objectives of which was to assess the level of compliance with thromboembolic prophylaxis and early rehabilitation. For thromboembolic prophylaxis, compliance improved from 62.7% to 100%, and for early rehabilitation from 58.8% to 66.7%. For the latter, compliance was not as high as expected. This is a fundamental aspect of patient care that affects their recovery and potential problems. An in-depth study was conducted to analyse the situation, with the idea of promoting early rehabilitation and drawing up a protocol.

To do this, they first recruited a team of nurses who could participate in the development of the work, taking into account their research skills and professional background (a total of 7 nurses). During the first meetings, an analysis was made of the shortcomings identified in the unit. A literature review was then conducted to identify interventions and protocols to ensure safe and effective mobilisation of patients. Observations of practice regarding the early mobilisation of patients were made and surveys of nursing staff were conducted. This led to the conclusion that there are multiple barriers to early mobilisation and that these barriers are consistent with those found in the literature. Given the multi-professional nature of the issue, it was decided to ask the medical team and the clinical rehabilitation service to collaborate in the design and implementation of the protocol, which contributed to its development. The protocol is based on two algorithms, one on the criteria to be taken into account for the safe mobilisation of patients and the other in which patients are divided into different groups.13

In addition, to implement the policy, training sessions were held for the ICU staff, two posters were displayed in the unit and materials were purchased to assist in the mobilisation of patients.

In addition, in order to determine the type of mobilisation for patients, some changes were made to the computer record, such as the Richmond Agitation and Sedation Scale (RASS) and the Scale for Muscle Strength (MRC).

It can be seen that in this example of developing evidence-based practice, the APN has implemented other skills such as leadership (with the research team), coaching (with the nursing team), decision making, and collaboration (with the medical team and rehabilitation service).

As with mobilisation to prevent thromboembolism, each year the APN creates a working group to focus on an area of improvement in the unit, in line with the annual objectives set. This group conducts a literature review on the topic to be worked on, formulates a research question, and carries it out. The results are presented in the unit, at the annual congress of the Spanish Society of Intensive Care Nursing and published in intensive care journals. This internal and external (scientific community) communication plan aims to improve care in the unit itself and in other ICUs. In this sense, since their incorporation into the unit, the APN has studied pain in post-operative ICU patients,14 sleep in ICU patients,15 ICU professionals’ knowledge of pain16 and palliative care,17 respiratory physiotherapy,18 work-related stress of ICU professionals,19 and ICU patient satisfaction with nursing care.20

In addition, the APN has participated in several R&D&I projects of the University of Navarra and other organisations. For example, it is currently working on the project "Excelencia en Enfermería. Proyecto de Traslación del Conocimiento de la Enfermería de Familia, en la práctica clínica, en oncología" (Excellence in Nursing. Project for the Translation of Family Nursing Knowledge into Clinical Practice in Oncology).

Outcomes in the clinical history care recordIn the ICU of the CUN, one of the objectives is to make the nursing work visible, and the computerised recording of all nursing actions carried out by the nurses is essential. To this end, patient records are checked daily to ensure that the aspects being worked on at the time are correctly recorded and completed. Below are the results of a study on the recording of bacteraemia (Fig. 2), ventilator-associated pneumonia (Fig. 3), and urinary tract infections (Fig. 4). All show an improvement in computerised recording and therefore in nursing practice.

Outcomes of trainingIn addition, since the integration of the APN into the team, more than 100 training sessions have been organised for the staff of the area, with an average satisfaction rating of more than 3.5/4. The training sessions sought to address the needs identified in practice (limitation of therapeutic effort, care of patients on long-term mechanical circulatory support, etc.).

Another part of the APN’s training role is to coordinate the master's degree on "Formación Permanente en Cuidados Especializados de Enfermería en Cuidados Intensivos" (continuing education in specialised care of intensive care nurses). In addition to coordinating, they also teach on this master’s degree and mentor all students, providing them with daily support and guidance in practice.

ConclusionThe results obtained confirm the impact of the APN role on the nursing team and patient care, improving the quality and safety of care.

In such a high-tech and physically and emotionally complicated environment as the ICU, the APN plays a fundamental role in accompanying patients, families, novice, and experienced nurses, etc. The inclusion of an APN in the CUN ICU was therefore key to highlighting the essence of nursing and the impact this role has on people's lives and on achieving the objectives of the unit, the institution, and ministerial objectives.

The author has no conflict of interest to declare.