In January 2020, the Chinese authorities identified a new virus of the Coronaviridae family as the cause of several cases of pneumonia of unknown aetiology. The outbreak was initially confined to Wuhan City, but then spread outside Chinese borders. On 31 January 2020, the first case was declared in Spain. On 11 March 2020, The World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the coronavirus outbreak a pandemic. On 16 March 2020, there were 139 countries affected. In this situation, the Scientific Societies SEMICYUC and SEEIUC, have decided to draw up this Contingency Plan to guide the response of the intensive care services. The objectives of this plan are to estimate the magnitude of the problem and identify the necessary human and material resources. This is to provide the Spanish Intensive Medicine Services with a tool to programme optimal response strategies.

En enero de 2020 China identificó un nuevo virus de la familia de los Coronaviridae como causante de varios casos de neumonía de origen desconocido. Inicialmente confinado a la ciudad de Wuhan, se extendió posteriormente fuera de las fronteras chinas. En España, el primer caso se declaró el 31 de enero de 2020. El 11 de marzo, la Organización Mundial de la Salud declaró el brote de coronavirus como pandemia. El 16 de marzo había 139 países afectados. Ante esta situación, las Sociedades Científicas SEMICYUC y SEEIUC han decidido la elaboración de este plan de contingencia para dar respuesta a las necesidades que conllevará esta nueva enfermedad. Se pretende estimar la magnitud del problema e identificar las necesidades asistenciales, de recursos humanos y materiales, de manera que los servicios de medicina intensiva del país tengan una herramienta que les permita una planificación óptima y realista con que responder a la pandemia.

On January 7, 2020, the Chinese authorities identified a new virus in the Coronaviridae family as the cause of an outbreak of pneumonia in the city of Wuhan in Hubei Province. The virus has subsequently been named SARS-CoV-2 and the disease, COVID-19.1

According to data from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), from 31 December 2019 to 16 March 2020 the disease had spread to 139 countries, and there were 16,741 reported cases, including 6507 deaths.2

In Spain, according to data from the Ministry of Health, on 16 March at 13:00 there were 9191 positive cases, of which 432 were admitted to intensive care units (ICU).3

In this situation, the scientific societies SEMICYUC, representative of specialists in Intensive Care Medicine, and SEEIUC, representative of critical care nurses, are considering the need to develop a contingency plan to respond to the needs that this new disease will entail, with the following objectives:

- 1.

To provide health authorities, managers and clinicians with a technical document that addresses all aspects related to identifying the care needs of critically ill patients in the face of the new SARS-Cov-2 pandemic, for the comprehensive and realistic planning of intensive care services at national, regional and hospital level.

- 2.

To ensure optimum care for severely ill COVID-19 patients and other critical patients with other diseases.

- 3.

To limit the nosocomial spread of COVID-19:

- •

To protect health and non-health workers in all ICUs.

- •

To prevent hospitals serving as amplifiers of the disease.

- •

To protect non- COVID-19 patients from infection, in order to maintain the capacity to provide essential non-COVID-19 medical care.

- •

- 4.

To optimise the human resources of intensive care services.

- 5.

The rational, ethical and organised allocation of limited healthcare resource to ensure the greatest good for the greatest number of people.

The proposal for planning possible scenarios is based on FluSurge 2.0 software. It was developed by the CDC and provides a freely downloadable spreadsheet to estimate the demand for services, in both a moderate and severe pandemic situation.4 The tool allows changes of the population at risk, the available hospital resources and assumptions on the epidemiological course of the pandemic, and then provides a rough estimate of needs in that context. Thus, it estimates the number of hospitalisations and deaths, the number of people hospitalised, the number of patients requiring care in ICU, how many of these people will require mechanical ventilation and the degree of saturation of the services available to care for them.

It is important to highlight that FluSurge 2.0 has been specifically designed to assess the possible effect of a pandemic caused by the influenza virus and has been validated only for that purpose. Its application to the COVID-19 pandemic should be approached with caution.

The calculation of possible scenarios requires several initial assumptions about the characteristics of the pandemic. The estimates used are based on the published series on the Chinese outbreak,5,6 the experience in Italy7 and experience with the influenza virus H1N1.8

A mean hospital stay of 11 days, a mean ICU stay of 14 days, a rate of 11% of hospitalised patients requiring ICU admission and 6.5% requiring mechanical ventilation were considered.

Considering an attack rate (proportion of persons within a population who become infected with a certain disease) of 35% and a duration of the pandemic of 12 weeks (data that are adjusted to the progression of the most affected Autonomous Communities), the following are expected:

- •

278,435 hospital admissions in 12 weeks.

- •

Peak demand in week 7.

- •

The need for more than 9000 ICU beds at times of greatest demand.

- •

The need for more than 5000 ventilators in the weeks of greatest demand.

The proposed scenario has been designed to plan for needs in the event that containment measures are not sufficient. The following are recommended:

- •

Plan according to the actual situation at any given time.

- •

Re-evaluate progression in response to containment measures.

It is recommended that the response be adapted in line with progression of the pandemic.9,10

Phase 0. Preparedness- •

Normal care activity.

- •

Elaboration of protocols and contingency plan.

- •

Bed availability study.

- •

Equipment forecast.

- •

Staff training.

- •

Cancellation of elective surgery.

- •

Fitting of additional spaces such as ICU beds.

- •

Completing staff teams. Freeing-up of extra- ICU activity.

- •

Sectorised work teams.

- •

Suspension of all elective activity.

- •

Organise shifts.

- •

Sectorise COVID-19 patients.

- •

Strict admission criteria.

- •

Prioritise the care of patients most likely to recover.

- •

Nurse: patient ratio based on availability.

- •

Prioritise the overall benefit to the individual.

The coronavirus committees are working groups at national, regional and local levels (specific to the hospital) that prepare the necessary resources and the action plan for all possible scenarios.

The committees have the following objectives:

- •

To define and agree the contingency plan with the administration.

- •

To guarantee the acquisition of material.

- •

Complete the necessary protocols.

- •

Plan spaces.

- •

Define procedures for transfer.

- •

Organise the work teams.

The role of the intensive care specialist on the committees is essential to:

- •

Prepare pathways and areas for critical patient care.

- •

Define hospital and out-of-hospital transfer pathways.

- •

Report on the situation and the needs of the ICU.

The following recommendations have been established:

- •

Critical COVID-19 patients must be cared for in an ICU by specialists in intensive care medicine.

- •

Each ICU bay or station must be equipped with a ventilator for advanced invasive ventilation.

- •

There must be a transport ventilator for every 10 patients.

- •

All of these aspects must be considered when creating extraordinary ICU bays in other areas of the hospital.

- •

Cohorting and isolation in cohorts is recommended.

- •

Cohorting should take precedence over the concept of closed-door rooms.

- •

If an ICU has both open and closed bays, it is recommended that closed bays are used initially.

- •

If necessary, extend the physical space of the ICU.

A plan for change in care must be made in each centre to include burden sharing, care responsibilities and working hours.

The following staffing of intensive care doctors is recommended11:

Ordinary working hours:

- -

One intensive care specialist for every 3 patients.

- -

In the event of saturation, other non-intensive care physicians (including resident physicians) can be included, coordinated by an intensive care specialist.

On-call duty:

- -

Two intensive care specialists or 1 intensive care specialist plus 1 4th/5th-year resident for every 12 beds.

- -

In the event of saturation, other non-intensive doctors (including resident doctors) coordinated by an intensive care specialist.

The following nursing staffing is recommended12:

- •

One nurse per shift for every 2 critical patients.

- •

Back-up of 1 nurse for every 4–6 beds for support in moments of maximum workload (prone, intubation, transfers, etc.).

- •

One Assistant Nursing Care Technician (TCAE) for every 4 beds.

- •

Back-up per shift every 8–12 beds for organisation and cleaning of material, support and replacement.

SEMICYUC will edit the training material: computer graphics, posters, etc.

Each hospital must organise training sessions with at least the following content:

- -

Epidemiology of COVID-19.

- -

Impact on activity.

- -

Transmission.

- -

Diagnosis of COVID-19.

- -

Personal protection measures: personal protective equipment (PPE), procedures and isolation.

We recommend13:

- •

Establishing an information transfer period.

- •

Avoiding close contact during information transfer.

- •

Special care in handing off the therapeutic plan and anticipating changes.

- •

Undertaking structured hand-offs, e.g. through SBAR (Status, Background, Assessment and Recommendations).

- •

Appropriate completion of clinical history.

- •

In ICUs where there are cases of COVID-19, it is recommended that the relatives of all patients admitted to the ICU should be informed on a daily basis, as well as when there are no cases, without providing any additional information that could infringe on the privacy of the patient and his/her family.

- •

It is recommended that all family members of patients admitted to an ICU where there are COVID-19 cases receive the usual daily information provided by the team outside the unit.

- •

COVID-19 patients will be kept in isolation and accompaniment/visits completely restricted. Only in situations reviewed on an individual basis by the care team due to compelling need (e.g. near death) or other clinical, ethical and/or humanitarian considerations, will limited, controlled,short, supervised visits be permitted on an exceptional basis, after training the family member how to put on and take off PPE by helping and supervising them.

- •

Families are advised to keep the accompaniment of patients, whether or not they have COVID-19, to a minimum.

Visits to patients without COVID-19 in units where COVID-19 patients have been admitted will be adapted to the architectural characteristics of the unit.

Optimised use of resourcesCoronaviruses are mainly transmitted by respiratory droplets of more than 5μm and by direct contact with secretions from infected patients. They may also be transmitted by aerosols in therapeutic procedures that produce them. Therefore, we recommend14–17:

- •

Precautions for the treatment of all probable or confirmed patients under investigation should include standard, contact and droplet transmission precautions.

- •

Strict hand hygiene should be observed.

- •

All professionals should be trained in the use of PPE.

- •

Ideally, patients should be isolated in a separate room, if possible, with negative pressure.

- •

Priority should be given to cohorting in a specific area.

- •

Waste generated is considered class III waste.

- •

PPE should be removed inside the bay, with the exception of respiratory and eye protection.

- •

Clothing and dishes do not require special treatment-

Equipment must include14:

- •

Gloves and protective clothing.

- •

Respiratory protection.

- •

Eye and face protection.

We recommend the following in terms of respiratory protection14, 16:

Confirmed cases under investigation should wear surgical masks if possible.

Use 2 high efficiency antimicrobial filters (inspiratory and expiratory branches) in the case of invasive mechanical ventilation.18

Use closed suction systems.

For non-invasive ventilation, the use of anti-viral filters and preferably double-tube equipment is recommended.

Avoid manual ventilation with a bag mask. If this is done, a high efficiency antimicrobial filter should be used.

Avoid active humidification, aerosol therapy and circuit breakers.18

To enter the room or a 2m perimeter, if procedures that generate aerosols are not going to be performed, it is recommended that the following are used15:

- -

Gown (can be disposable paper).

- -

Mask (surgical or FFP2 if available and ensuring sufficient stock at all times).

- -

Gloves.

- -

Anti-splash eye protection.

If an aerosol-generating procedure is to be performed, the following are recommended16, 18:

- -

FFP2 or preferably FFP3 mask, if available.

- -

Tight fitting full frame eye protection or full-face shield.

- -

Gloves.

- -

Long-sleeved waterproof gown.

The current recommendation is to use the mask only once. Although there is no clear evidence on this, in the event of a shortage, the masks can be reused by the same practitioner for a maximum period of 8h of continuous or intermittent activity. There can be extended use of the mask if it is not stained or wet.19

Optimising the use of PPERational use of PPE is necessary and exposure times must be minimised. To this end, the following recommendations should be followed:

Promote registration, control and monitoring measures that do not require entering the room.

- •

Plan tasks and remain in the room for the shortest time possible.

- •

Group tasks that require entering the bay.

- •

Adjust perfusions to make changes during one programmed entry to the bay.

- •

Deliver care, examinations, etc., with the minimum number of people.

- •

Do not suction by protocol.

- •

Take samples together to prevent unnecessary entries.

- -

Prepare the sample for sending inside the bay.

- -

Clean the external part of the tube with a surface disinfectant or wipe impregnated with disinfectant.

- -

Samples will be transported in person avoiding transport systems such as pneumatic tubes.

The professionals responsible for the patient should supervise any action on the patient by non-service personnel.

Indications for admission to ICU due to SARS-CoV-2 pneumoniaGeneral criteria for admission to ICU

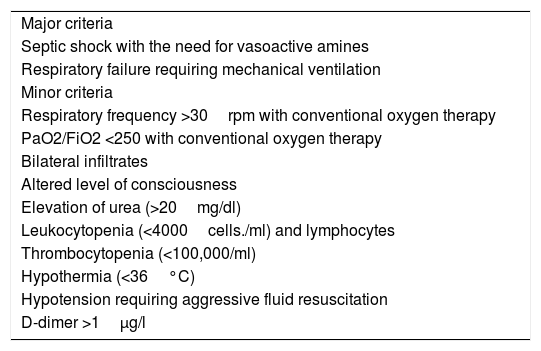

We recommend using objective criteria for ICU admission based on the recommendations of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA)20 and recent evidence from analysis of the SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) epidemic in China21 (Table 1). ICU admission will be considered when there is 1 major criterion or 3 or more minor criteria.

Major and minor criteria for admission to the intensive care unit (ICU).

| Major criteria |

| Septic shock with the need for vasoactive amines |

| Respiratory failure requiring mechanical ventilation |

| Minor criteria |

| Respiratory frequency >30rpm with conventional oxygen therapy |

| PaO2/FiO2 <250 with conventional oxygen therapy |

| Bilateral infiltrates |

| Altered level of consciousness |

| Elevation of urea (>20mg/dl) |

| Leukocytopenia (<4000cells./ml) and lymphocytes |

| Thrombocytopenia (<100,000/ml) |

| Hypothermia (<36°C) |

| Hypotension requiring aggressive fluid resuscitation |

| D-dimer >1μg/l |

Optimisation in the event of saturation

- •

In a situation of saturation or being overrun, it is necessary to prioritise the care of the cases that are potentially more likely to recover.

- •

ICU triage protocols for pandemics should only be activated when ICU resources over a wide geographic area are or will be overwhelmed despite all reasonable efforts to expand resources or obtain additional resources.

- •

Guidelines for adjusting therapeutic effort are essential.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria22–25

- •

A triage instrument that objectively classifies patients is proposed.

- •

The only measure proposed so far, although not validated, is based on the use of SOFA.22

- •

After the first assessment, patients should be reassessed on days 2 and 5, when they could be reclassified.

The following are exclusion criteria for admission:

- •

Poor prognosis despite ICU admission.

- •

Need for resources that cannot be provided.

- •

Not meeting severity criteria

- •

The specific recommendations for admission exclusion criteria in the event of a mass disaster can be applied.25

The expansion plan includes the transformation and fitting out of additional spaces for the care of the critical patient in the event that ICU beds have been overwhelmed and enlarging the team of staff who are experts in critical care.

Expansion of intensive care servicesPossible sites for critical patients must have22,26,27:

- •

Medical gases.

- •

Respirators for invasive and non-invasive mechanical ventilation.

- •

Possibility of high-flow oxygen therapy.

- •

Possibility of advanced monitoring.

- •

Possibility of continuous extrarenal purification techniques.

- •

Points for hand hygiene.

- •

The availability of central monitoring (telemetry) would be desirable.

As a guideline, the spaces that can be used to extend ICU beds are28:

- •

Intermediate care units attended by intensive care specialists: nurse:patient ratios need to be adjusted to those of a conventional ICU.

- •

Resuscitation units and post-anaesthetic recovery units. Elective surgery must be suspended. Patients must be cared for by specialists in intensive medicine.

- •

Critical or intermediate care areas of the emergency services.

- •

Make space available near the ICU with new equipment.

- •

Transform conventional hospitalisation areas, day hospitals or major outpatient surgery areas.

- •

In the event of overcrowding, transfer to another centre with available space should be considered.

We recommend that, if 100% saturation of intensive care services is anticipated, centralisation of resources should be considered. To that end:

- •

Develop an inter-hospital transfer procedure.

- •

A critical patient coordinator should be designated in each Autonomous Community to comprehensively manage all the critical beds in each Community.

We recommend29,30:

Conducting a census of all medical personnel who specialise in intensive care medicine, to also include:

- -

Physicians with on-call contracts.

- -

Intensive care specialists dedicated to other tasks in the hospital.

- -

Unemployed doctors.

- -

Recent retirees.

- •

Conduct a census of other staff physicians or residents who may have the capacity to care for less serious patients, coordinated by the intensive care department.

- •

Extending substitution contracts.

- •

Carry out a plan for medical staffing and burden sharing in all hospitals.

- •

Conduct a census of nursing staff with knowledge and experience in critical patient care.

- •

Develop a plan to relocate experienced nurses to critical areas

- •

Consider the peak care load in forecasts.

- •

If medical or nursing staff who are not undertaking their usual work are included in critical care activities, they should first receive training.

- •

Training should include 2 key areas: intensive care medicine or nursing and infection control.

- •

Necessary personnel: attending physician, attending nurse and emergency health technician.

- •

Appropriate PPE for the staff in the care cabin is recommended for situations where there is aerosol risk.

Consider the following during transfer:

- •

The driver must be isolated from the patient's compartment.

- •

Family members must not travel in the transport vehicle.

- •

Limit the number of care providers in the care cabin.

- •

A protocol for the transfer pathway must be established: itinerary, elevator, number of participants, PPE.

- •

Steps for transfer:

- 1.

Inform the receiving department of the start of the transfer.

- 2.

Prepare the material.

- 3.

Place PPE.

- 4.

Inform the receiving department of the start of the transfer.

- 5.

Block the lift for transfer and disinfection.

- 6.

Security personnel with a surgical mask will precede the team to clear the area.

- 7.

Disinfection of trafficked areas.

- 8.

Return.

None.

President, Ricard Ferrer Roca; Vice president, Álvaro Castellanos Ortega; Secretary, Josep Trenado Álvarez; Vice-secretary, Virginia Fraile Gutiérrez; Treasurer, Alberto Hernández Tejedor; President of the Scientific Committee, Manuel Herrera Gutiérrez; Vice-President of the Scientific Committee, Paula Ramírez Galleymore; Member for Working Groups, M. Ángeles Ballesteros Sanz; Member for the Autonomous Societies, Pedro Rascado Sedes; Member for Doctors in Training, Leire López de la Oliva Calvo; Former President, María Cruz Martín Delgado.

President, Marta Raurell Torredá; Vice-president, Miriam del Barrio Linares; Secretary, Marta Romero García; Treasurer, María Teresa Ruiz García; Journal Editor, María Pilar Delgado Hito; Member for Working Groups, Juan José Rodríguez Mondéjar; Member for Industry, Carmen Moreno Arroyo; Member for International Relations, Alicia San José Arribas; Member for Research, María Jesús Frade Mera.

The members of the Junta directiva de la SEMICYUC appear in Appendix A.

Please cite this article as: Rascado Sedes P, Ballesteros Sanz MÁ, Bodí Saera MA, Carrasco RodríguezRey LF, Castellanos Ortega Á, Catalán González M, et al. Plan de contingencia para los servicios de medicina intensiva frente a la pandemia COVID-19. Enferm Intensiva. 2020;31:82–89.

This article is published simultaneously in Medicina Intensiva (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.medin.2020.03.006) and in Enfermería Intensiva (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfi.2020.03.001), with the consent of the authors and editors.