The objective of this study was to investigate whether music therapy affects immediate postoperative well-being among patients who had undergone TKA surgery in the recovery unit.

MethodA randomized controlled trial was conducted recruiting patients from Hospital Melaka, Malaysia. Postoperative TKA patients with good hearing and visual acuity, fully conscious and prescribed with patients controlled analgesia (PCA) were randomized to either intervention or control groups using a sealed envelope. Patients in the intervention group received usual care with additional music therapy during recovery, while patients in the control group received the usual care provided by the hospital. Two factors identified affecting mental well-being were the pain (measured using numerical rating scale) and anxiety (measured using a visual analog scale) at five different minutes’ points (0, 10, 20, 30, and 60).

ResultsA total of 56 (control: 28, intervention: 28) postoperative TKA patients consented in the study. There was no difference in baseline characteristics between the two groups (p>0.05). Using Mann–Whitney U tests, patients in music therapy group showed significantly lower numerical pain score at 60min (p=0.045) whereas there was no significant difference between the two groups at all time points for anxiety scores (p>0.05). In the intervention group, Friedman tests showed that there was a significant difference in numerical pain (χ2=36.957, df=4, p<0.001) and anxiety score across times (χ2=18.545, p=0.001).

ConclusionsThis study found that pain score decreases over time among patients in the music therapy group while no effect is seen for anxiety. It is suggested that music therapy could not affect postoperative TKA patients’ mental well-being. Nonetheless, patients reported better pain score despite the small sample.

Epidemiologically, it is reported that half of the people aged 65 and above have osteoarthritis (OA), portraying the most dominant of joint disorders among people in the world.1 In Malaysia, the most common form of reported OA is knee OA.2 Various treatments are recommended for knee OA including the surgical, pharmacological and non-pharmacological approach.3 Among all, the surgical treatment of total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has the greatest evidence that is effectively reducing the prominent symptoms of pain and function improvement for most of the suitable patients in long-term.4 It is also reported that most patients with knee OA are satisfied with the surgery.5 After undergoing TKA surgery, patients experience high levels of pain and anxiety that interferes with their lives, jeopardizing their mental well-being, and many reported to have pain sensitization problems.6,7 Among patients undergoing surgery, pain and anxiety are two common stressors. The emotional state of nervousness, tension, and worry could be aloof by mediating its effect or removing the cause through supportive interventions. In order to prevent further complications among patients, nurses and healthcare professionals should promote not only physical well-being8 but also mental well-being.

In Malaysia, patients undergoing TKA are prescribed with medications that could decrease their level of pain. They are observed in the recovery area or unit for a certain period for monitoring. At this time, the pain is extremely affecting the patients. Other than pharmacological intervention, patients are also encouraged to have strong support and conducive environment to reduce pain and also allay anxiety. Many studies have focused on objectives that include decreasing pain, reducing anxiety, increasing relaxation, increasing coping skills, and improving the quality of life.9 In the recovery unit, little is known about the effectiveness of music therapy as a distraction technique to manage the pain. In various studies, results have shown that participants who listened to music had a lower state of anxiety and pain levels than those who did not listen to music.10–12 Sedative music or types of music that are specifically composed to have soothing effects can be accommodating in relaxation.13 In line with the wide use of music in a clinical situation, it is advisable that music becomes a part of nursing care offered to patients experiencing pain because music is a low-cost therapy that has no side effects.14 Thus, this study aimed to investigate whether music therapy affects immediate postoperative well-being among patients undergoing TKA surgery in the recovery unit.

MethodA randomized controlled trial study was conducted at a recovery unit of the operating theater, Hospital Melaka, Malaysia, between January and May 2018. This hospital is a tertiary referral center in Melaka including nearby districts from Negeri Sembilan and Johor with a yearly TKA surgery of approximately 190 cases. Registered nurses and pain services specialists provided patients’ care in this unit.

Patients were eligible for inclusion if they were aged 18 and above undergoing TKA under central neural block (spinal, epidural or epidural combined spinal), good hearing and sight, good interaction to understand Malay language instructions, oriented to person, place and time, prescribed with patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) as postoperative pain management and preoperatively classified as class 1, 2 or 3 based on the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA). They were excluded if using antipsychotic drugs, allergy to opioids, unstable hemodynamic and admitted to the intensive care unit after the surgery. On the basis of the effect of music on pain and vital signs among postoperative patients,15 the sample size was calculated based on the expected mean difference of 5.0 and standard deviation (SD) of 6.3 between two groups. From the calculation, a total of 25 patients were required in each group and allowing 10% dropout, the total number for the sample size was 28 patients in each group.

Patients were approached at Anesthesia clinic or Orthopedics ward based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria. We contacted the potential participants a week before the surgery to provide information about the study. Patients were given 24–48h to decide either to participate or not. Patients consented to participate were randomized by immediately being given a selection of envelopes containing letter ‘A’ (indicative of intervention group) and ‘B’ (indicative of a control group) to choose from. Participants randomized to the control group received the usual care provided by the hospital based on current practice. This care included management of pain, oxygenation, ventilation, medication (analgesic and anti-emetic), fluids, observation of general condition, monitoring of the level of consciousness, vital signs, side effects of anesthesia, and wound care. On the other hand, participants randomized to the intervention group were provided with a selection of music in addition to the usual care.

The research protocol was reviewed and approved by the Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Research Ethics Committee (Ref: UKM FPR.4/244/8/FF-2017-501) and the Medical Research Ethics Committee (MREC), Ministry of Health Malaysia (Ref: NMRR -17-2761-38055 (IIR)).

Patients randomized to the intervention group were given the list of music from which they chose before undergoing surgery. Listening to self-selected music is a simple strategy to minimize anxiety.16 Music therapy intervention in this study was managed by interveners who are nurses holding a certificate of perianaesthesia care nursing and attended regular training in music therapy. They were supervised by anaesthesiologists and appointed head nurse for music therapy. The music consisted of Celtic Flutes, Worlds Flutes, Beethoven's Moonlight, Native American Flute and Guitar, Peaceful Harp and Chopin's Nocturne which were offered due to its harmonious dancing melody and rhythm that have shown tranquil results and improved well-being.17 Based on local context, ‘zikir’ (a type of religious music) was also included as one of the music options since it is also proven to have a therapeutic effect in emotions and psychology.18 For therapy, any music heard by the patient should have a sedative quality and should be given according to cultural choice.14 That music selection has 60–80 beats per minute or less to lower the chance of increasing the pulse rate caused by entertaining music. The selection of music provided encourages the patient to relax. The music also has a continuous melody, without strong rhythm or drumming.

Participants in the intervention group were provided with MP3 players and headphones that contain music during admission to the recovery unit. The music was played by the intervener to the patients once admitted for up to 60min using an MP3 player. The use of headphones was pretested before given to patients to ensure that it worked well for the patients. In practice, the minimum time spent in the recovery unit was recorded as 30min before being discharged to their respective wards. However, the patients were remained in the recovery unit based on their condition in terms of consciousness level, breathing, circulation, and color where every patient is required to achieve a score of six based on the anesthetic record, Ministry of Health Malaysia. A maximum of 60min in the recovery unit was set for all participants of this study to fully recover from the effect of the central neural blockade and was ascertained through the value of the Bromage Score although the various range of effective listening times from a minimum of 15–20min,19 60min among Malaysian people of listening to music does not interrupt any daily routine in the recovery unit.20

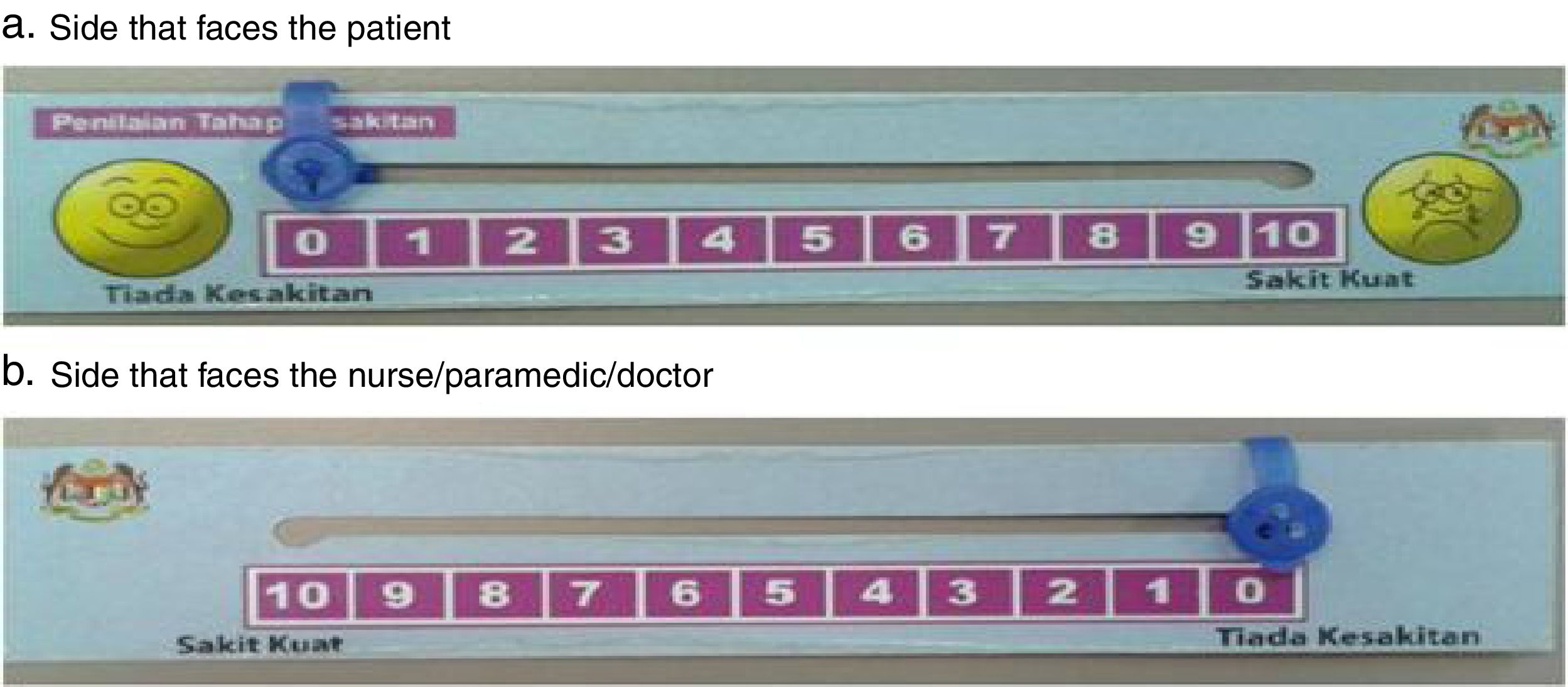

On the basis of previous intervention studies, we selected the outcomes for dependent variables of pain and anxiety. Our understanding was that these two outcomes were responsible for psychophysiological response to stress within the context of TKA surgery. Data were collected using a numerical rating scale (NRS) for pain and a visual analog scale (VAS) for anxiety completed by the patients at five different minutes’ points (0, 10, 20, 30, and 60) in the recovery unit. The measurement of pain was achieved using NRS provided by the Ministry of Health (MoH) Malaysia which is a scalar ruler comprising of 10 horizontal line indicators with exact angles at each end of the word link which illustrates the extreme pain (see Fig. 1). The leftmost part indicates “no pain” and the most right-tailed part indicate an “extreme pain”. Patients were required to adjust indicators on a scale that illustrates the severity of the pain experienced (Fig. 2).

Anxiety was measured using a scale of 10cm horizontal lines with a right angle at each end of the link indicating “no concern” on the left-most part shown “very concerned” at the far right.17 Patients indicated on a line where they think their anxiety level falls on the continuum on that line. The ruler was used to measure the leftmost scale to the mark written by the patients. Length measurements are measured and written in millimeter (mm). Reliability and validity of VAS were done by conducting test–retest reliability using the intra-class correlation coefficient (ICC) between VAS for every 1min. The results showed that VAS is a reliable tool with ICC=0.99 (95% CI 0.989–0.992).21 In addition, validity was assessed by an analysis of variance (ANOVA), looking at the linear trend with the association between the five categories of pain and changes in VAS. The results show that VAS is a valid tool in their study population and their environment (F=79.4, p<0.001).17

All data were entered regularly and checked to identify any errors during the entry of the item and analyzed using IBM statistical package for the social sciences (SPSS) version 20. Normality tests were conducted before the data inference analysis process. The differences in terms of demographic and clinical characteristics between intervention and control groups were performed using the Chi-square test, independent t-test, and Mann–Whitney test. The total number of categories of demographic data for the ethnicity, marital status and types of anesthesia were categorized into two categories, while the religious status and levels of education were reduced to three and four categories respectively. This is to meet the assumption for the Chi-square test, where the lowest frequency of any cell at least 5 or more.22 Mann–Whitney test was also used to analyze the differences in the pain and anxiety scores between the groups. The pain and anxiety scores across time points were compared using the Friedman test and post hoc test was used to determine where significant differences exist. The conventional p less than 0.05 was used to determine the level of significance.

ResultsA total of 56 patients agreed to participate and randomized to control (28 patients) and intervention (28 patients) groups. All patients enrolled in this study were similar characteristics at baseline concerning age, gender, ethnicity, marital status, religious belief and level of education in both groups (p>0.05) (Table 1). As expected, more women than men had undergone surgery in both groups (women: 38; men 18). For the intervention group, the age range was 38–82 years, the majority of patients were Malay (n=16, 57.1%), married (n=28, 100% 16, 57.1%) and level of education at high school (n=19, 67.9%). In the control group, majority of patients were married (n=26, 92.9%), Islam (n=18, 64.3%) and level of education at high school (n=12, 42.9%).

Demographic characteristics of the patients in the control and intervention groups.

| Variable | Control group (n=28) | Intervention group (n=28) | Total (N=56) | Statistical value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD) | |||||

| Age | 64.50 (8.851) [range 49–82] | 63.71 (11.005) [range 38–82] | 64.11 (9.903) [range 38–82] | −0.294a | 0.770 |

| N (%) | |||||

| Gender | |||||

| Male | 9 (32.1) | 9 (32.1) | 18 (32.1) | 0.000b | 1.00 |

| Female | 19 (67.9) | 19 (67.9) | 38 (67.9) | ||

| Ethnicity | |||||

| Malay | 19 (67.9) | 16 (57.1) | 35 (62.5) | 0.305b | 0.581 |

| Chinese | 8 (28.6) | 9 (32.1) | 17 (30.4) | ||

| Indian | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Others | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Marital status | |||||

| Single | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8%) | n.a | 0.491 |

| Married | 26 (92.9) | 28 (100.0) | 54 (96.4%) | ||

| Divorcee | 1 (3.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.8%) | ||

| Religious belief | |||||

| Islam | 18 (64.3) | 16 (57.1) | 34 (60.7) | 3.041b | 0.219 |

| Buddhism | 4 (14.3) | 9 (32.1) | 13 (23.2) | ||

| Hinduism | 0 (0.0 | 2 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Christianity | 2 (7.1) | 1 (3.6) | 3 (5.4) | ||

| Others | 4 (14.3) | 0 (0.0) | 4 (7.1) | ||

| Level of education | |||||

| No formal education | 6 (21.4) | 1 (3.6) | 7 (12.5) | 5.485b | 0.140 |

| Primar school | 7 (25.0) | 5 (17.9) | 12 (21.4) | ||

| Secondary school/SPM | 12 (42.9) | 19 (67.9) | 31 (55.4) | ||

| Diploma/STPM | 0 (0.0) | 2 (7.1) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Degree | 1 (3.6) | 1 (3.6) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Others | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) | ||

The findings of the clinical characteristics of patients are shown in Tables 2 and 3. The pre-operative pain level ranges from 0 to 6 where the maximum pre-operative pain level for the intervention group is lower than the control group of two scores. The duration of surgery ranges from 80 to 210min and was shorter in the control group (85–180min). The majority of patients in the intervention group underwent TKA surgery under the spinal anesthesia (n=23, 82.1%), no medication was given during the intraoperative phase (n=27, 96.4%) and post-operative (n=26, 92.9%). The amount of opioid received by the patients’ ranges from 0mg to 14mg of morphine. The majority of patients in the control group underwent surgery under the spinal anesthesia (n=23, 82.1%), no medication was administered during the intraoperative phase (n=23, 82.1%) and post-operative (n=28, 100%) and the amount of opioid received by the patients ranges from 0mg to 12mg of morphine. However, the result of the inferential analysis showed that there was no significant difference between the two groups for all clinical data features (p>0.05). Meanwhile, Bromage Score indicated that there is no significant difference between the two groups in all five periods (p>0.05).

Clinical characteristics of the patients in the control and intervention groups.

| Variable | Intervetion (n=28) | Control (n=28) | Total (N=56) | Statistical value | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean (SD)/n (%) | Mean (SD)/n (%) | Mean (SD)/n (%) | |||

| Pre-operative pain level (baseline) | 0.25 (0.645) [0–2] | 0.75 (1.531) [0–6] | 0.50 (1.191) [0–6] | −1.350a | 0.177 |

| Duration of surgery | 143.11 (33.430) [80–210] | 133.18 (28.127) [85–180] | 138.14 (31.018) [80–210] | 1.203c | 0.234 |

| Types of anesthesia | |||||

| Spinal | 23 (82.1) | 23 (82.1) | 46 (82.1) | 0.000b | 1.000 |

| Epidural | 4 (14.3) | 1 (3.6) | 5 (8.9) | ||

| CSE | 1 (3.6) | 4 (14.3) | 5 (8.9) | ||

| Intra-operative medication | |||||

| Nil | 27 (96.4) | 23 (82.1) | 50 (89.3) | 1.680b | 0.195 |

| Midazolam | 1 (3.6) | 5 (17.9) | 6 (10.7) | ||

| Post-operative medication | |||||

| Nil | 26 (92.9) | 28 (100.0) | 54 (96.4) | n.a | 0.491 |

| Maxolon | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 2 (3.6) | ||

| Opiod total | 2.36 (4.34) [0–14] | 2.77 (3.27) [0–12] | 2.56 (3.82) [0–14] | −1.471a | 0.141 |

CSE, combined spinal epidural.

Clinical characteristics between the two groups based on Bromage score.

| Variable | Intervention (n=28)Median, mean rank | Control (n=28)Median, mean rank | U | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bromage Score Time 1Ketibaan di RecoveryUnit | 1, 30.25 | 0.5, 26.75 | −0.855 | 0.392 |

| Bromage Score Time 210min | 1, 30.21 | 0, 26.79 | −0.848 | 0.396 |

| Bromage Score Time 320min | 0, 30.43 | 0, 26.57 | −0.992 | 0.321 |

| Bromage Score Time 430min | 0, 29.57 | 0, 27.43 | −0.610 | 0.542 |

| Bromage Score Time 560min | 0, 28 | 0, 29 | −0.361 | 0.718 |

U=Mann–Whitney test.

Table 4 shows the results of pain and anxiety scores between the intervention and control groups. The intervention group had lower pain scores than the control group for all time points (0, 10, 20, 30 and 60min). However, only at minutes 60, the pain score between the two groups was significant (U=277, z=−2004, p=0.045) with a small effect size of 0.27. Meanwhile, there was no significant difference in the level of anxiety between the intervention and control groups at any time points (p>0.05).

Pain scores between intervention and control groups.

| Pain score | Intervention (n=28)Median, mean rank | Control (n=28)Median, mean rank | U | p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time 1Arrival at recovery (0min) | 0, 25.68 | 2, 31.32 | 313 | 0.171 |

| Time 210min | 0, 25.5 | 2, 31.5 | 308 | 0.146 |

| Time 320min | 0, 25.7 | 1.5, 31.3 | 313.5 | 0.174 |

| Time 430min | 0, 24.82 | 2, 32.18 | 289 | 0.075 |

| Time 560min | 0, 24.39 | 1.5, 32.61 | 277 | 0.045* |

U=Mann–Whitney.

The pain levels among those who received the music therapy were also significantly different across times (a χ2=36.957, df=4, p<0.001). Post hoc showed the significant differences were between almost all time points except between arrival time in the recovery unit (0min) and 10min (see Table 5). The effect size for the differences was within the range of 0.27–0.395, and this means that the size of the difference is moderate according to Cohen's schedule (1988).23

Post hoc test of pain scores.

| Time point (min) | Pain scores | Anxiety scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| z | p value | z | p value | |

| 0–10 | −2.333 | 0.20 | 0.000 | 1.000 |

| 0–20 | −2.724 | 0.006* (0.364**) | −1.732 | 0.83 |

| 0–30 | −2.716 | 0.007* (0.363**) | −2.236 | 0.025* (0.299**) |

| 0–60 | −2.953 | 0.003* (0.395**) | −2.333 | 0.020* (0.311**) |

| 10–20 | −2.070 | 0.038* (0.277**) | −1.732 | 0.083 |

| 10–30 | −2.716 | 0.007* (0.363**) | −2.236 | 0.025* (0.299**) |

| 10–60 | −2.956 | 0.003* (0.395**) | −2.333 | 0.020* (0.311**) |

| 20–30 | −2.456 | 0.014* (0.328**) | −1.414 | 0.157 |

| 20–60 | −2.844 | 0.004* (0.380**) | −2.000 | 0.046* (0.267**) |

| 30–60 | −2.333 | 0.020* (0.312**) | −1.414 | 0.157 |

z=Wilcoxon signed rank test.

Table 5 also shows there were differences in the anxiety levels between times in the intervention groups (χ2=18.545, df=4, p=0.001). Based on the post hoc tests, the differences were found to occur between arrival at recovery unit (0min) to 30min, arrival at recovery unit to 60min, 10min to 30min, 10min to 60min and 20min to 60min. The effect size ranges from 0.267 to 0.311.

DiscussionThe purpose of this study was to determine the effectiveness of music therapy in decreasing pain and anxiety among patients undergoing TKA surgery in the recovery unit. In this study, therapeutic music intervention therapy is in addition to routine activities that include the prescription of analgesia. The findings indicated that patients receiving music therapy reported lower pain score after the TKA surgery as compared to a control group after minutes of 60.

The positive outcome of music therapy on pain in this study is consistently found in another study during the rehabilitation period for patients who underwent TKR surgery.24 The absence of significant differences in the intensity of pain between the groups for other time points could be due to the strong effect of prescribed analgesia. According to the Surgical and Emergency Medical Services Unit (2013), the duration of action of the central neural blockade is 2–3h for epidural, 1–4h for the spinal, and the combined spinal-epidural (CSE) which is almost the same for both types of anesthetics i.e. 1–4h.25 The average duration of surgery within the range of 80–210min for all respondents, added with a duration of 60min of music intervention. Thus, this makes the patient's length of time within the effect of anesthesia and analgesia for approximately 4h. The effects of analgesia may have decreased in the fifth time i.e. 60min of listening to music. The result is consistent with Nillson et al. (2005), showing that a lower level of pain for the intervention group listening to music as compared to the control group for patients with open hernia repair after one hour admitted to the post anesthesia care unit (PACU).26 The results also show that the intervention of music therapy could be one of the indicators to improve the quality of postoperative pain management complementing to analgesics.27

In addition to the difference in the level of pain among the group at minutes 60, the study also found that there was a difference in the level of pain between the time intervals of the intervention group. Interestingly, the differences occurred at almost all time intervals of the intervention group with a medium effect size except between minutes 0 and 10 only. It is suggested that the effectiveness of music therapy also depends on how much the patient likes the music28 as patients in this study were given the choice of their music selection. Furthermore, in this study, most subjects in the intervention group chose ‘zikir’ as the preferred music. This type of music which based on holy Quranic verses has been known to affect the intensity of pain.28

Unlike the pain, there was no significant difference observed in this study in the level of anxiety between patients participated in the music therapy and control group. The possible reason could be the prescribed drugs produce various levels of depression of the central nervous system and consequently may have mediated the effect of the music intervention. The routine use of the prescribed drugs among the patients may have intervened in the sympathetic response to stress through depressing cardiac function and lowering the heart rate. The type or amount of music may not have been adequate to influence the psychophysiological response if combined with pharmacological agents. In the future, it could be good to explore the acceptability of various amount of drugs used and the effectiveness of the non-pharmacological intervention in reducing the level of anxiety among patients undergoing TKA surgery. This multi-modal analgesia helps protect patients from post-operative anxiety and emotional discomfort associated with pain sensations.20 However, in this study, it is unknown whether the two groups received the same amount of anesthesia or the possibility of a control group receiving more anesthesia from the intervention group which caused their level of anxiety to be the same as the intervention group even though they did not receive music therapy. Another reason could also be due to a silent resting atmosphere as in the recovery that was found to be effective in reducing the degree of anxiety as well.17

Although the level of anxiety in the study had no difference between the intervention and control groups, the level of anxiety in the group receiving music therapy showed a significant reduction over time intervals. Previous studies have shown that decreased levels of anxiety were associated with decreased levels of pain.29 The decrease in anxiety level in this study may be due to its association with lower postoperative pain levels as well. This is in line with the significant pain change in duration over time with a decrease in the level of anxiety.

This study is believed to be among the first in Malaysia using the element of ‘zikir’ to influence the level of pain and anxiety of the patients postoperatively. Unfortunately, we did not determine patients’ preference for music to be played other than seven musical pieces provided during the intervention. In retrospect, we could have asked patients to have their choice of music based on recommended harmonious and melodic tone as part of the local context preference. Meanwhile, the music was played for a period lasting only 60min in the recovery room. To prolong the effect of the desired therapy using music, repeated therapeutic interventions is suggested30 within 12h postoperatively could also be offered until admitted to the respective ward.20 This study also was conducted at one recovery unit only which could not be generalized to all patients undergoing TKA in Malaysia. Thus, the findings provided should be interpreted carefully because of these study limitations. Future studies are suggested to embrace a larger sample from a different place in Malaysia and should also include contextual preference and a larger selection of music.

In summary, music is a safe, non-invasive therapy for promoting pain management among postoperative TKA patients in the recovery unit. Although patients spontaneously reported using music therapy was beneficial for their pain. Anxiety level was decreased throughout the time of admission to the rehabilitation unit within the music therapy group. The music offered to patients should be culturally appropriate selections of a sedative quality. Future research could explore various selection of local context music for the TKA patients in a longer term, before the surgery until immediately after surgery. The music therapy does not harm the TKA patients. Thus it seems to be a supportive intervention in managing pain and decreasing anxiety in the recovery unit.

Conflict of interestsThe authors declare no conflict of interest.

Peer-review under responsibility of the scientific committee of the Second International Nursing Scholar Congress (INSC 2018) of Faculty of Nursing, Universitas Indonesia. Full-text and the content of it is under responsibility of authors of the article.