In Spain HIV testing is recommended to people with risk behaviors for HIV and with indicator conditions (IC) related to HIV infection. Missed diagnostic opportunities (MO) are defining as situations where these recommendations are not followed.

ObjectiveTo characterize MO due to risk behaviors (directed) and due to IC (indicated) among people diagnosed with HIV in the Region of Madrid.

MethodsA total of 109 participants newly diagnosed with HIV were recruited from 7 health centers (April 2018-March 2019) by a telephone survey. Diagnostic opportunities were defined as any contact with the healthcare system in which an HIV test should have been carried out. Frequency of MO was calculated within the previous 2 years from HIV diagnosis.

ResultsOf the 32 directed and indicated diagnostic opportunities, 96.9% and 57.8% respectively resulted in MO. Overall, 83.8% of diagnostic opportunities resulted in MO.

ConclusionMO, both directed and indicated, are an important area for improvement to reduce late diagnosis.

La oferta dirigida de la prueba de VIH está recomendada en personas con prácticas de riesgo y en enfermedades indicadoras de VIH. Las oportunidades diagnósticas perdidas (OP) son aquellas donde no se cumplen estas recomendaciones.

ObjetivoConocer el porcentaje de OP según práctica de riesgo (OP dirigidas) y condiciones indicadoras (OP indicadas) en la Comunidad de Madrid.

MétodosSe reclutaron 109 personas con nuevo diagnóstico de VIH en 7 centros sanitarios (abril 2018- marzo 2019) mediante encuestas telefónicas. Se definió oportunidad diagnóstica como cualquier contacto con el sistema sanitario en el que debería haberse realizado la prueba de VIH. Se calculó la ocurrencia de OP en los 2 años anteriores al diagnóstico de VIH.

ResultadosDe 32 oportunidades diagnósticas dirigidas e indicadas, un 96,9% y 57,8% respectivamente derivaron en OP. Globalmente, el 83,8% de las oportunidades diagnósticas resultaron en OP.

ConclusiónLas OP son una importante área de mejora en el diagnóstico precoz de VIH.

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection is a persistent public health problem in Spain. Every year, 3,500−4,500 new diagnoses are reported, and nearly half are late diagnoses1.

The impact of late diagnosis on morbidity and mortality in patients with HIV and the contribution thereof to new infections have been extensively described2,3. To improve early diagnosis of HIV, in 2014, the Spanish Ministry of Health published guidelines with healthcare recommendations that included testing for HIV in people with clinical criteria consistent with HIV infection (called indicator conditions [ICs]) and in people who engage in practices that could represent a higher risk of becoming infected with HIV4. Despite these recommendations, missed opportunities (MOs) for diagnosis — occasions on which people who meet the above requirements have contact with the health system and are not offered HIV testing — remain common5,6.

New diagnoses of HIV in the Autonomous Community of Madrid (ACM) account for approximately 23% of all cases reported annually in Spain1, and around 40% of diagnoses are made when the patient has a CD4 count below 350 cells/μl7.

The objective of this study was to analyse MOs due to ICs (indicated) and due to risk practices (directed) among new HIV diagnoses in the ACM.

MethodsThis was a cross-sectional study in people over 16 years of age residing in the ACM and diagnosed with HIV between 1 April 2018 and 31 March 2019. Participants were selected by convenience sampling between June and September 2019 at the Centro de ITS Montesa [Montesa STI Centre], Centro Sanitario Sandoval [Sandoval Health Centre], Hospital Universitario La Paz [La Paz University Hospital], Hospital Universitario Ramón y Cajal [Ramón y Cajal University Hospital], Hospital Universitario Gregorio Marañón [Gregorio Marañón University Hospital], Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre [12 de Octubre University Hospital] and Hospital Clínico San Carlos [San Carlos Clinical Hospital]. Those whose command of Spanish prevented them from completing the survey were excluded.

A telephone interview with 34 questions adapted from pre-existing questionnaires was conducted6,8. The following variables were collected: (a) sociodemographic variables; (b) variables related to risk practices calling for directed testing (gay, bisexual or other men who have sex with men [GBMSM]; transsexual women who have sex with men; three or more sexual partners; engagement in sex work; injected drug use or sexualised drug use [chemsex]) and disclosure thereof; (c) nature of test leading to diagnosis; and d) opportunities for diagnosis (ODs) of HIV and MOs (considering disclosure to be a dichotomous variable, with “yes” meaning disclosure to the different resources used and “no” meaning concealment from any of them).

An OD was defined as any contact with a healthcare resource in the two years prior to diagnosis in which HIV testing was recommended5, classified as follows:

- OD for directed testing: if the person had engaged in any risk practice calling for testing. Participants with multiple instances of contact were asked about the most recent.

- OD due to an IC: visit for general signs or symptoms (fever of unknown origin for more than a month, idiopathic chronic diarrhoea that was recurrent and/or lasted longer than a month, unexplained weight loss exceeding 10%), mucocutaneous signs (herpes zoster, candidiasis or idiopathic lymphadenopathy), pulmonary tuberculosis or an STI (hepatitis A, B or C; syphilis; gonorrhoea; chlamydia, genital herpes; human papillomavirus; lymphogranuloma venereum; genital mycoplasma; or trichomoniasis).

- MO: any OD that did not result in testing being offered. ODs that occurred in the three months prior to HIV diagnosis were considered potentially related to said diagnosis and therefore not included in the analysis.

A descriptive analysis of the participants who completed the entire questionnaire was performed. In those having had any contact with the health system in the two years prior to their diagnosis, a bivariate analysis was performed to determine whether there were any differences with regard to the occurrence of MOs by gender identity, age, region of origin, place of residence, years of residence in the ACM, level of education or occupational status. In people who engage in risk practices calling for directed testing, the possibility of a relationship between the disclosure of said practices and MOs was assessed. The study was approved by the Instituto de Salud Carlos III [Carlos III Health Institute] Independent Ethics Committee (HIP-CI-CEI-PI-20_2019v3) and funded by Madrid Salud [Madrid Health].

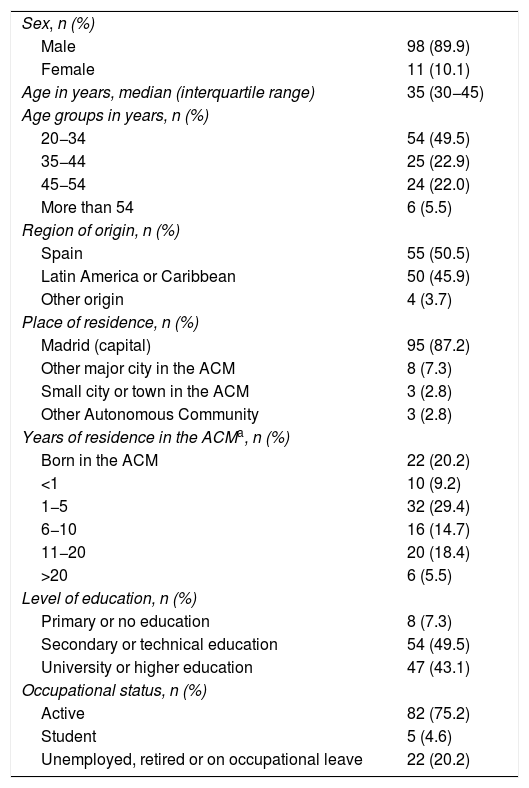

ResultsOf the 144 participants screened, 111 (77.1%) completed the entire questionnaire. Two transsexual women who had sex with men were excluded from the analysis for lack of a larger sample of such individuals. Ultimately, the sample consisted of 109 participants (Table 1).

Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants (n = 109).

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Male | 98 (89.9) |

| Female | 11 (10.1) |

| Age in years, median (interquartile range) | 35 (30−45) |

| Age groups in years, n (%) | |

| 20−34 | 54 (49.5) |

| 35−44 | 25 (22.9) |

| 45−54 | 24 (22.0) |

| More than 54 | 6 (5.5) |

| Region of origin, n (%) | |

| Spain | 55 (50.5) |

| Latin America or Caribbean | 50 (45.9) |

| Other origin | 4 (3.7) |

| Place of residence, n (%) | |

| Madrid (capital) | 95 (87.2) |

| Other major city in the ACM | 8 (7.3) |

| Small city or town in the ACM | 3 (2.8) |

| Other Autonomous Community | 3 (2.8) |

| Years of residence in the ACMa, n (%) | |

| Born in the ACM | 22 (20.2) |

| <1 | 10 (9.2) |

| 1−5 | 32 (29.4) |

| 6−10 | 16 (14.7) |

| 11−20 | 20 (18.4) |

| >20 | 6 (5.5) |

| Level of education, n (%) | |

| Primary or no education | 8 (7.3) |

| Secondary or technical education | 54 (49.5) |

| University or higher education | 47 (43.1) |

| Occupational status, n (%) | |

| Active | 82 (75.2) |

| Student | 5 (4.6) |

| Unemployed, retired or on occupational leave | 22 (20.2) |

ACM: Autonomous Community of Madrid.

More than 90% of them engaged in any risk practice calling for directed testing (78.9% were GBMSM, 74.3% had three or more sexual partners and 24.8% practised chemsex). Two or more of these practices were reported by 68.8% of the participants. The healthcare resources with the highest rates of disclosure were STI centres (83.8% in GBMSM, 80.0% in people with ≥3 partners and 68.8% in chemsex users). These rates were lower in accident and emergency departments (37.1% in GBMSM, 17.2% in people with ≥3 partners and 19.1% in chemsex users). The lowest rate of disclosure corresponded to chemsex in primary care (13.6%).

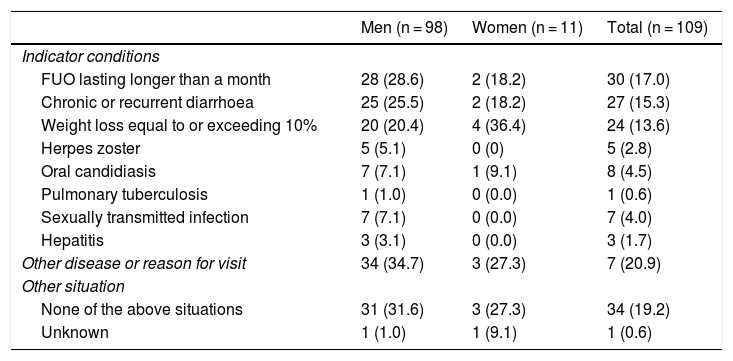

Fifty-two men (53.1%) and five women (45.5%) were diagnosed with HIV as a result of an IC-related visit (p = 0.076) (Table 2). Primary care centres were the healthcare resources in which the participants were most commonly diagnosed with HIV, followed by centres for STIs in men (20.4%).

Reason for visit leading to HIV diagnosis, by sex. Multiple responses.

| Men (n = 98) | Women (n = 11) | Total (n = 109) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indicator conditions | |||

| FUO lasting longer than a month | 28 (28.6) | 2 (18.2) | 30 (17.0) |

| Chronic or recurrent diarrhoea | 25 (25.5) | 2 (18.2) | 27 (15.3) |

| Weight loss equal to or exceeding 10% | 20 (20.4) | 4 (36.4) | 24 (13.6) |

| Herpes zoster | 5 (5.1) | 0 (0) | 5 (2.8) |

| Oral candidiasis | 7 (7.1) | 1 (9.1) | 8 (4.5) |

| Pulmonary tuberculosis | 1 (1.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) |

| Sexually transmitted infection | 7 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) | 7 (4.0) |

| Hepatitis | 3 (3.1) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.7) |

| Other disease or reason for visit | 34 (34.7) | 3 (27.3) | 7 (20.9) |

| Other situation | |||

| None of the above situations | 31 (31.6) | 3 (27.3) | 34 (19.2) |

| Unknown | 1 (1.0) | 1 (9.1) | 1 (0.6) |

FUO: fever of unknown origin; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus.

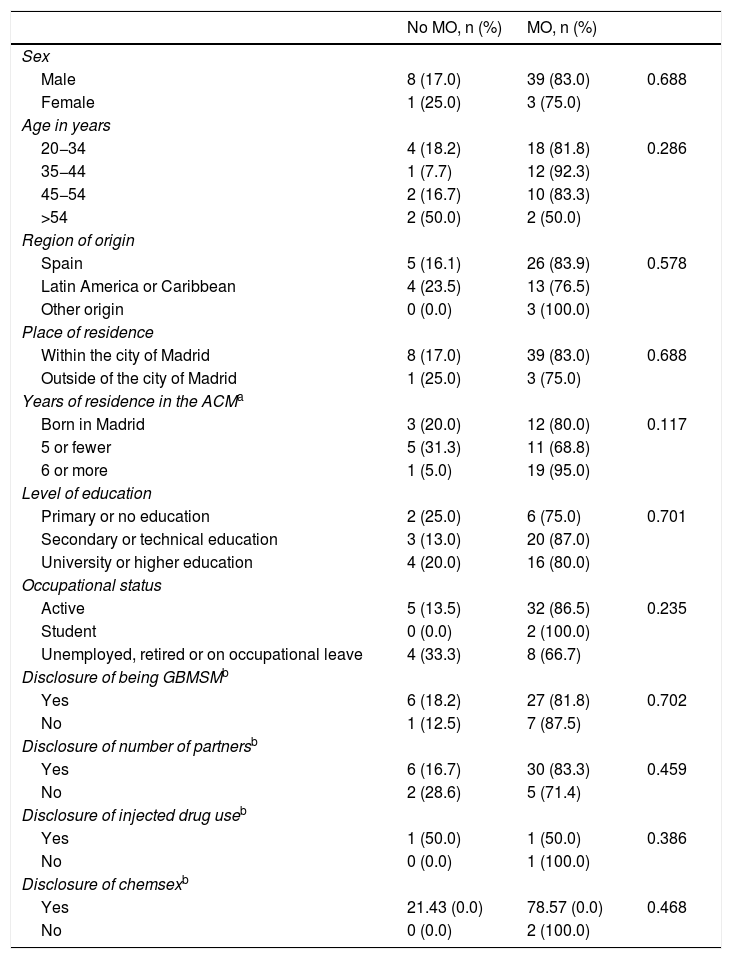

Forty-nine participants (45.0%) experienced at least one OD. Of them, 41 stated that they had not been offered the test, representing a rate of 83.8% (95% confidence interval [CI] 70.3–92.7) of MOs for this group (88.4% in men and 75.0% in women, p = 0.624). No significant differences were found between those who experienced MOs and those who did not. In total, there were 57 MOs: one in 28 people, two in 10 people and three in three people.

Of the 32 directed ODs, 50% occurred in primary care. Out of all ODs, 96.9% (95% CI 83.8–99.9) resulted in MOs for directed testing (all in men). The highest rates of MOs for directed testing were seen in primary care (15 MOs, 100%), hospital visits (6 MOs, 100%) and accident and emergency departments (6 MOs, 85.7%).

Thirty-four participants had 44 ODs due to ICs. More than half (n = 23) took place in primary care. The rest occurred in accident and emergency departments (n = 6), STI centres (n = 3), hospital visits (n = 1) or other (n = 3). These ODs resulted in an MO in 59.1% (n = 26) of cases (45% in men and 60% in women). ODs resulted in MOs at rates of 60.9% (n = 14) in primary care, 72.7% (n = 8) in visits to other types of healthcare resources and 50% (3) in accident and emergency departments, and the only OD in a hospital visit resulted in an MO. None of the three ODs due to ICs that occurred at STI centres resulted in an MO.

No statistically significant differences were found (Table 3).

Differences between occurrences of opportunities by exposure variables among participants who had any contact with the health system in the two years prior to their HIV diagnosis (n = 80).

| No MO, n (%) | MO, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 8 (17.0) | 39 (83.0) | 0.688 |

| Female | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Age in years | |||

| 20−34 | 4 (18.2) | 18 (81.8) | 0.286 |

| 35−44 | 1 (7.7) | 12 (92.3) | |

| 45−54 | 2 (16.7) | 10 (83.3) | |

| >54 | 2 (50.0) | 2 (50.0) | |

| Region of origin | |||

| Spain | 5 (16.1) | 26 (83.9) | 0.578 |

| Latin America or Caribbean | 4 (23.5) | 13 (76.5) | |

| Other origin | 0 (0.0) | 3 (100.0) | |

| Place of residence | |||

| Within the city of Madrid | 8 (17.0) | 39 (83.0) | 0.688 |

| Outside of the city of Madrid | 1 (25.0) | 3 (75.0) | |

| Years of residence in the ACMa | |||

| Born in Madrid | 3 (20.0) | 12 (80.0) | 0.117 |

| 5 or fewer | 5 (31.3) | 11 (68.8) | |

| 6 or more | 1 (5.0) | 19 (95.0) | |

| Level of education | |||

| Primary or no education | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) | 0.701 |

| Secondary or technical education | 3 (13.0) | 20 (87.0) | |

| University or higher education | 4 (20.0) | 16 (80.0) | |

| Occupational status | |||

| Active | 5 (13.5) | 32 (86.5) | 0.235 |

| Student | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) | |

| Unemployed, retired or on occupational leave | 4 (33.3) | 8 (66.7) | |

| Disclosure of being GBMSMb | |||

| Yes | 6 (18.2) | 27 (81.8) | 0.702 |

| No | 1 (12.5) | 7 (87.5) | |

| Disclosure of number of partnersb | |||

| Yes | 6 (16.7) | 30 (83.3) | 0.459 |

| No | 2 (28.6) | 5 (71.4) | |

| Disclosure of injected drug useb | |||

| Yes | 1 (50.0) | 1 (50.0) | 0.386 |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) | |

| Disclosure of chemsexb | |||

| Yes | 21.43 (0.0) | 78.57 (0.0) | 0.468 |

| No | 0 (0.0) | 2 (100.0) |

ACM: Autonomous Community of Madrid; GBMSM: gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men; HIV: human immunodeficiency virus; MO: missed opportunity.

The highest numbers of MOs occurred due to fever of unknown origin (23.1%) or chronic diarrhoea (19.2%) (Table 2). The rate of MOs was higher in ICs other than an STI (78.3% versus 38.1%) (Table 3).

DiscussionThe overall rate of MOs was consistent with those found in other countries8,9, and the overall rate of MOs due to ICs (59.1%) was similar to that found in Spanish GBMSM in 2013 (52.8%)5.

The rate of disclosure of risk practices was low, especially in primary care, which might reflect barriers such as lack of privacy, lack of time, cultural competences and fear of discrimination10,11. Awareness of matters related to sexuality must be raised among health professionals. Training interventions have been shown to have a positive impact on testing in our context12.

The rate of MOs was higher for ICs other than an STI, especially in nonspecific conditions such as fever of unknown origin and chronic diarrhoea, consistent with findings from other authors6. This points to a need to improve training on ICs so that professionals have a high degree of suspicion in the event of their onset.

The importance of primary care is reflected in the finding that it was the resource where the most diagnoses were made, but where most of the ODs occurred. The types of resources with the highest rate of MOs were those categorised as “other”; most were private centres, so their role may be relatively significant.

Other studies have found a relationship between the disclosure of risk practices and a lower rate of MOs13. Our study did not find this relationship or any other. This could be due to its sample size.

Moreover, the low number of cases in women also precluded an in-depth analysis in this group. Our sample nevertheless represents approximately 10% of new diagnoses reported annually. Information was only collected on the most recent contact with a healthcare resource for directed ODs; this might have resulted in underestimation of rates of ODs and MOs. Another limitation of our study was its use of convenience sampling. A strength of the study was that it broadened the knowledge of MOs in the ACM.

Reducing MOs represents a clear opportunity to improve control of the HIV epidemic. It also entails opportunities to offer personalised prevention counselling, promote condom use and provide information on pre- and post-exposure prophylaxis to candidates for the use thereof.14 Diagnostic testing has been proposed as a strategy for linking people with negative results to preventive measures that is as effective as the cascade of care.15 Both strategies leverage HIV diagnostic testing as a starting point for patients who engage in risk practices. Reducing MOs is crucial for seizing this opportunity.

FundingThis project was funded by Madrid Salud.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

The authors of this study would like to thank all the participants for sharing their time and knowledge, and Sara del Arco for carrying out the project.

Members of the Fast-Track Madrid Working Group for the Study of Missed Opportunities: Teresa Valverde Higueras, Francisco Bru Gorraiz, David Rial-Crestelol, Santos del Campo, Isabel Gutiérrez Cuéllar, Oskar Ayerdi Aguirrebengoa, Vicente Estrada, Ana Delgado, Marta Rava, Asunción Díaz, Cristina Moreno and Inmaculada Jarrín.

Please cite this article as: Gallego-Márquez N, Iniesta C, Grupo de Trabajo para el Estudio de las Oportunidades Perdidas Fast-Track Madrid. Identificando objetivos fast-track: oportunidades perdidas en el diagnóstico de VIH en la Comunidad de Madrid. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:138–141.

The names of the components of the Fast-Track Madrid Working Group for the Study of Missed Opportunities are listed in the Annex.