Long-term care facilities (LTCFs) have become receptors of patients with a high risk of healthcare-associated infections (HAIs).

ObjectiveTo determine the prevalence of HAIs in LTCFs.

MethodDuring the period 2011–2014 2 annual prevalence studies were performed according to Healthcare-associated infections in long-term-care facilities (HALT) study definitions and methodology.

ResultsA total of 28,360 patients were included in the study. The overall prevalence rate of HAIs was 10.2%. Subacute units and palliative care units showed the highest rates, 22.3% and 18.7%, respectively. Main infections were respiratory tract infection (35.8%) and urinary tract infection (35.8%).

ConclusionThese results were higher than other similar experiences, a fact that suggests the need to extend the specific strategies and programs to LTCFs, and ensuring a sufficient number of specialised staff in infection control.

Los centros sanitarios de cuidados prolongados (CSCP) se han convertido en receptores de enfermos con un alto riesgo de aparición de infecciones relacionadas con la asistencia sanitaria (IRAS).

ObjetivoDeterminar la prevalencia de las IRAS en los CSCP de nuestro medio.

MétodoDurante el periodo 2011-2014 se realizaron 2 estudios anuales de prevalencia siguiendo las definiciones y metodología del estudio Healthcare-associated infections in long-term-care facilities (HALT).

ResultadosLa muestra final fue de 28.360 pacientes. La prevalencia de IRAS en los datos agregados fue de 10,2%. Las unidades de subagudos, con un 22,3%, y paliativos, con un 18,7%, fueron las que presentaron un mayor porcentaje de infecciones. Las infecciones más frecuentes fueron las respiratorias (35,8%) y las urinarias (35,8%).

ConclusiónLa prevalencia de infección en nuestros CSCP fue muy superior a la publicada en el estudio HALT. Nuestros resultados muestran la necesidad de desarrollar programas preventivos específicos en estos centros, garantizando un número suficiente de personal especializado en el control de las infecciones.

In recent years, healthcare in Spain has undergone significant changes. Acute care hospitals have a great need to refer hospitalised patients in the convalescent phase or patients with great dependence to long-term care facilities (LTCFs). The definition of long-term care facilities includes socio-healthcare facilities and community-based residences. Our LTCFs include long-term stay units (nursing homes), palliative care units, psychogeriatric and intermediate care units (step-down facilities). Intermediate care, for its part, would include units specialised in care for patients in sub-acute and post-acute situations and in convalescence units.1

These centres have become receptors of patients with a high risk of acquiring infections which are mainly related to their underlying conditions and the invasive procedures that they may undergo. This type of infection is more similar to a nosocomial infection than a community-acquired infection. As a result, the classic concept of nosocomial infection has been changed to the more current concept of healthcare-associated infection (HAI) that encompasses both types of infection.1

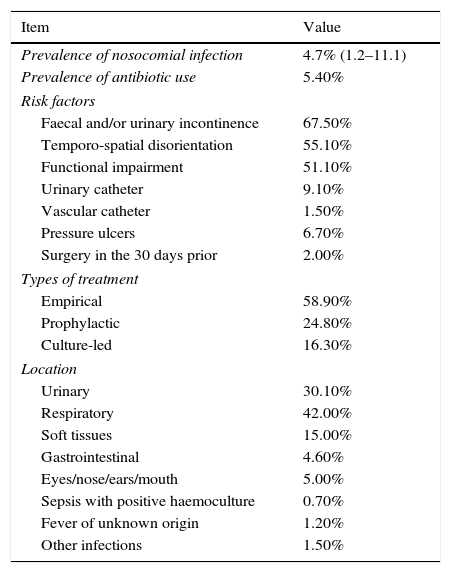

The information currently available about HAIs that occur in LTCFs is insufficient, and knowing the scope of the problem has become a major objective of epidemiological surveillance. This situation, common throughout Europe, caused the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) in 2010 to launch an annual study of prevalence, called Healthcare-associated infections in long-term-care facilities (HALT), to determine the prevalence of these infections, the use of antibiotics and the factors associated with HAIs. The diagnostic criteria were based on the clinical judgement of the physician based on the McGeer criteria (1991). The most prevalent results of the 2010 HALT study are shown in Table 1. In the results presented in the 2013 report, the prevalence of HAIs was around 3.4% (n=2626 of the 77,264 patients included in the study), with wide variations depending on the country; the most prevalent were respiratory tract infections (31.2%), followed by urinary tract infections (31.2%) and skin and soft tissue infections (22.8%). The prevalence of antibiotic use was around 4.4%, also with a wide variation between countries.2 Spain did not submit data to this study, having no nationwide information available, although there is information about the prevalence rates in large areas of the country, obtained from studies conducted in some autonomous communities.3–9 Since 2006, the Vigilancia de la Infección Nosocomial en Cataluña (VINCat) programme of the Servei Català de la Salut [Catalan Health Service] has been in existence. This establishes a unified surveillance system for nosocomial infections in hospitals and LTCFs in Catalonia. The mission of VINCat, directed by Dr Francesc Gudiol and a technical committee comprising professionals from various specialities, is to contribute to reducing the rates of these infections through active and ongoing epidemiological surveillance.1 The objective of this study is to determine the prevalence of HAIs in LTCFs in Spain.

Results of the HALT 2010 study.

| Item | Value |

|---|---|

| Prevalence of nosocomial infection | 4.7% (1.2–11.1) |

| Prevalence of antibiotic use | 5.40% |

| Risk factors | |

| Faecal and/or urinary incontinence | 67.50% |

| Temporo-spatial disorientation | 55.10% |

| Functional impairment | 51.10% |

| Urinary catheter | 9.10% |

| Vascular catheter | 1.50% |

| Pressure ulcers | 6.70% |

| Surgery in the 30 days prior | 2.00% |

| Types of treatment | |

| Empirical | 58.90% |

| Prophylactic | 24.80% |

| Culture-led | 16.30% |

| Location | |

| Urinary | 30.10% |

| Respiratory | 42.00% |

| Soft tissues | 15.00% |

| Gastrointestinal | 4.60% |

| Eyes/nose/ears/mouth | 5.00% |

| Sepsis with positive haemoculture | 0.70% |

| Fever of unknown origin | 1.20% |

| Other infections | 1.50% |

The data were collected via two prevalence studies that were conducted annually tween 2011 and 2014. To avoid seasonal biases, one was conducted in June and the other in October. During the study period, all the medical records of the patients admitted to the site were reviewed in 24h. The prevalence study must be done at all centres simultaneously. Although it would be ideal to review all patients admitted to the centre on a specific day (the same day for all participating centres), this is difficult to achieve. Therefore, a period of 15 days is provided to collect the data. It is recommended that the data from each hospitalisation unit be collected on a single day, including all admitted patients. Each bed at the centre must be reviewed once; empty beds do not need to be taken into account or reviewed again. The data collection was performed following the same definitions and methodology as the HALT study.2 For assignment of an HAI to a patient, the McGeer criteria adapted to surveillance of infections in LTCFs were applied.10 The surveillance was carried out by trained health professionals at the same centres. Two questionnaires were used: one about the residents and another about the site characteristics. All risk factors considered relevant for the comparison of the site characteristics were evaluated. The descriptive statistical analysis presents the prevalence of HAIs (%) where the variables are expressed in percentages, with the denominator being the total number of patients evaluated in the prevalence cut-off and the numerator being patients who had the event. SPSS version 20 software was used to conduct the analysis.

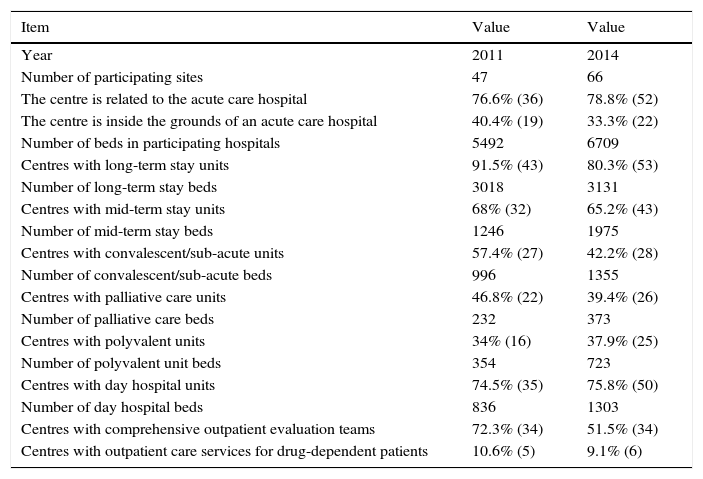

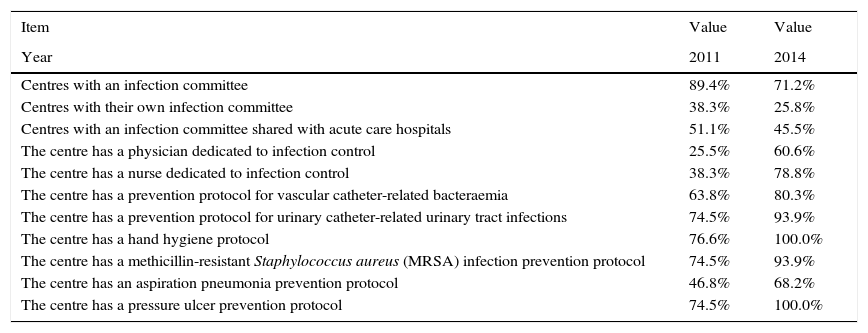

ResultsSite characteristicsThe number of participating sites increased from 47 (48%) in 2011 to 66 (63%) in 2015. Table 2 lists the characteristics of the participating sites in 2015, with a total of 6709 beds. It is notable that 52 sites (78%) are related to acute-care hospitals and, of those, 22 (33%) are located within the same grounds as the hospital. Regarding resources, the main results are presented in Table 3: 47 sites (71%) have an infections committee, 40 sites (60%) have a part-time dedicated physician and 52 (78%) have an infection-control nurse. Furthermore, more than 90% have protocols for hand hygiene, pressure ulcers, prevention of urinary tract infections, and prevention of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA); the number of sites with bacteraemia and aspiration pneumonia prevention protocols is much lower.

General characteristics of the evaluated sites.

| Item | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 2011 | 2014 |

| Number of participating sites | 47 | 66 |

| The centre is related to the acute care hospital | 76.6% (36) | 78.8% (52) |

| The centre is inside the grounds of an acute care hospital | 40.4% (19) | 33.3% (22) |

| Number of beds in participating hospitals | 5492 | 6709 |

| Centres with long-term stay units | 91.5% (43) | 80.3% (53) |

| Number of long-term stay beds | 3018 | 3131 |

| Centres with mid-term stay units | 68% (32) | 65.2% (43) |

| Number of mid-term stay beds | 1246 | 1975 |

| Centres with convalescent/sub-acute units | 57.4% (27) | 42.2% (28) |

| Number of convalescent/sub-acute beds | 996 | 1355 |

| Centres with palliative care units | 46.8% (22) | 39.4% (26) |

| Number of palliative care beds | 232 | 373 |

| Centres with polyvalent units | 34% (16) | 37.9% (25) |

| Number of polyvalent unit beds | 354 | 723 |

| Centres with day hospital units | 74.5% (35) | 75.8% (50) |

| Number of day hospital beds | 836 | 1303 |

| Centres with comprehensive outpatient evaluation teams | 72.3% (34) | 51.5% (34) |

| Centres with outpatient care services for drug-dependent patients | 10.6% (5) | 9.1% (6) |

Hospital availability.

| Item | Value | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Year | 2011 | 2014 |

| Centres with an infection committee | 89.4% | 71.2% |

| Centres with their own infection committee | 38.3% | 25.8% |

| Centres with an infection committee shared with acute care hospitals | 51.1% | 45.5% |

| The centre has a physician dedicated to infection control | 25.5% | 60.6% |

| The centre has a nurse dedicated to infection control | 38.3% | 78.8% |

| The centre has a prevention protocol for vascular catheter-related bacteraemia | 63.8% | 80.3% |

| The centre has a prevention protocol for urinary catheter-related urinary tract infections | 74.5% | 93.9% |

| The centre has a hand hygiene protocol | 76.6% | 100.0% |

| The centre has a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection prevention protocol | 74.5% | 93.9% |

| The centre has an aspiration pneumonia prevention protocol | 46.8% | 68.2% |

| The centre has a pressure ulcer prevention protocol | 74.5% | 100.0% |

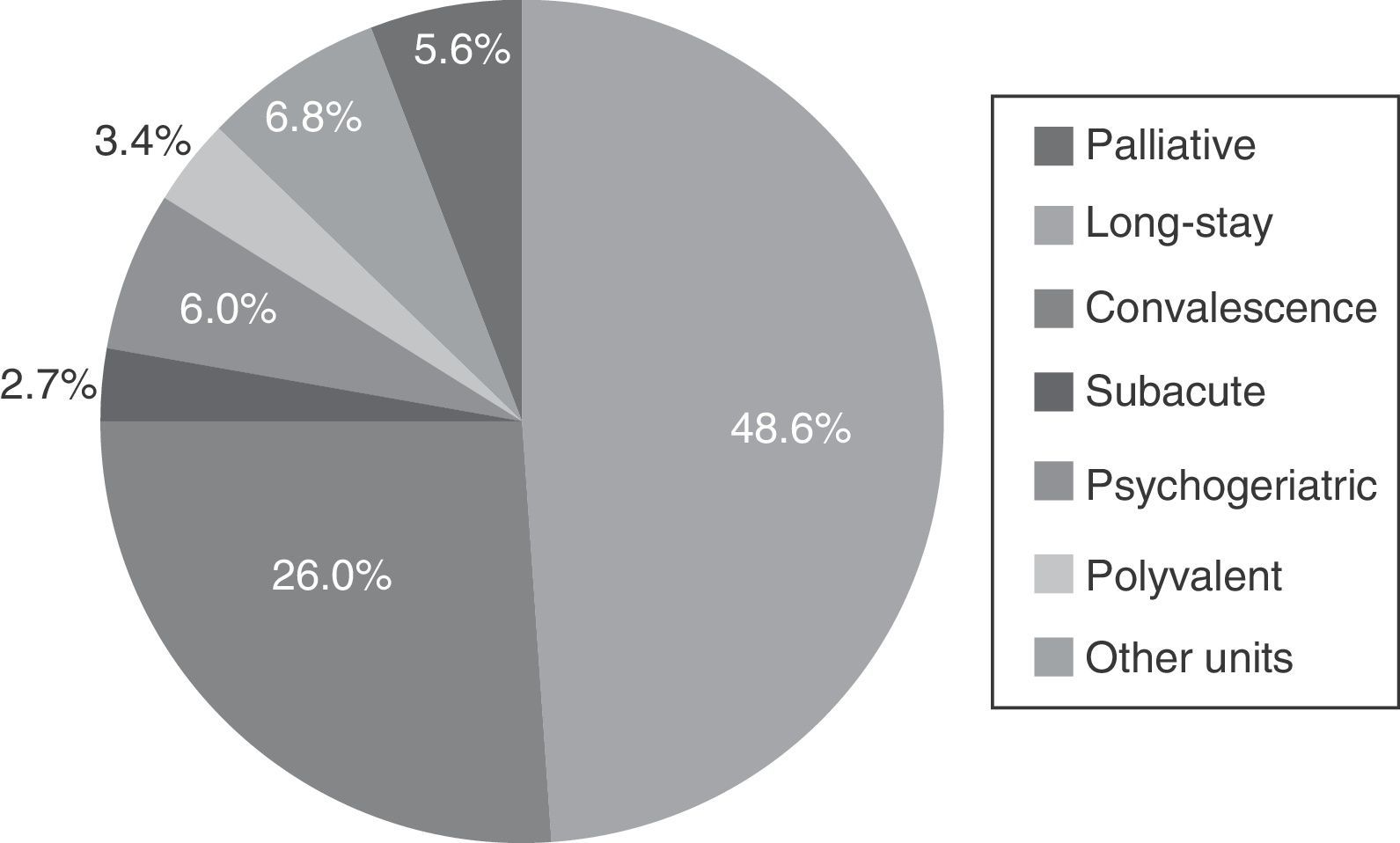

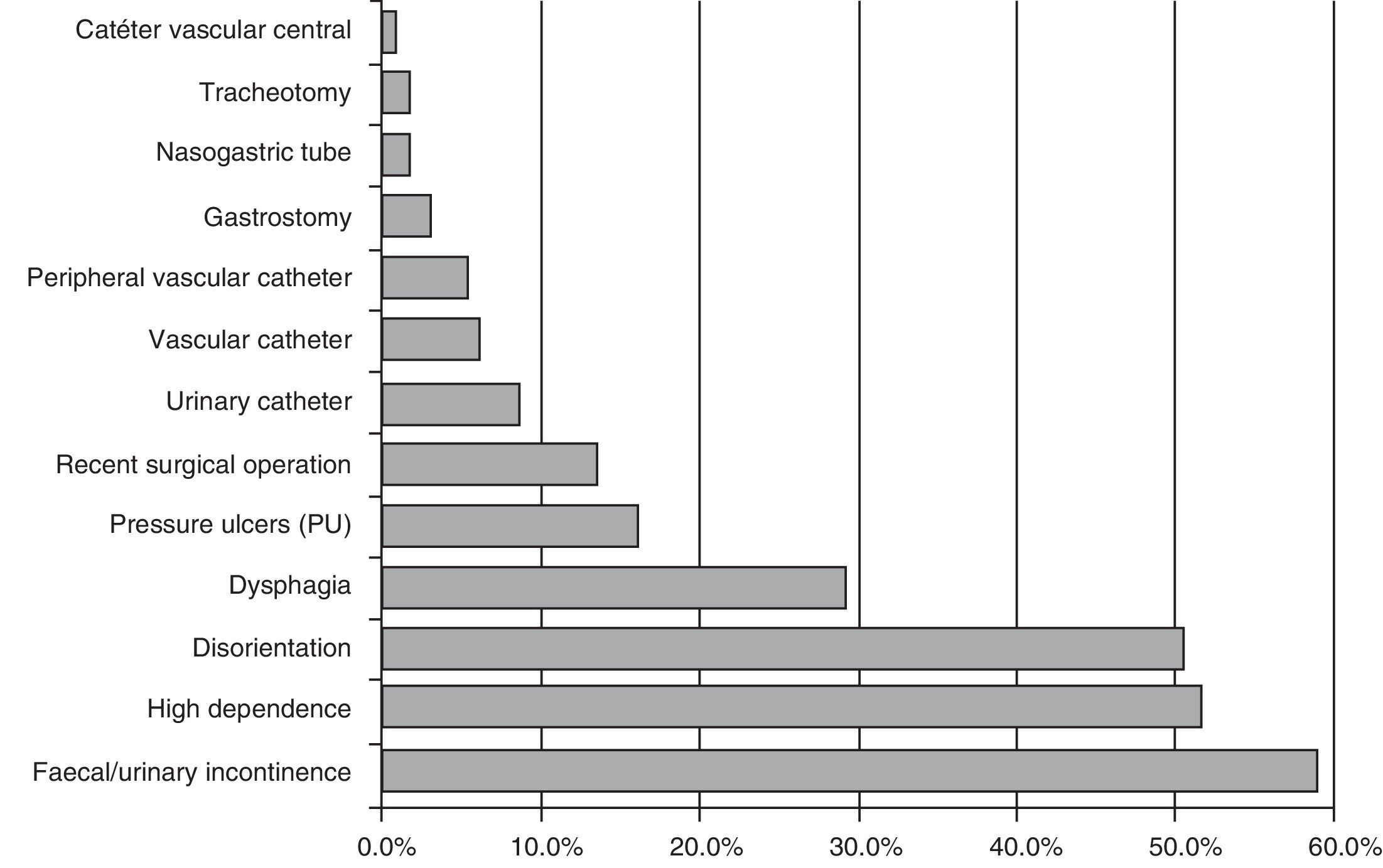

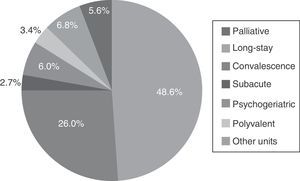

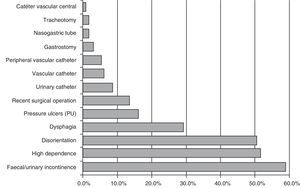

In the 8 studies conducted between 2011 and 2014, aggregate data were collected from 331 sites, with 28,360 patients studied. Of the total population, 58% were women, and the average age was 78, with 38% older than 85. 48% were admitted to long-term care units, 26% in convalescence units and the remaining 25% were proportionally divided between palliative, psychogeriatrics, sub-acute, and polyvalent care units. The list of patients that entered the study by hospitalisation unit type is shown in Fig. 1. Among the risk factors it should be noted that 60% had incontinence and 50% had disorientation and major dependence. The number of patients who had a surgical intervention in the 30 days prior to the study increased in all sections to 13%. The list of the main risk factors is shown in Fig. 2.

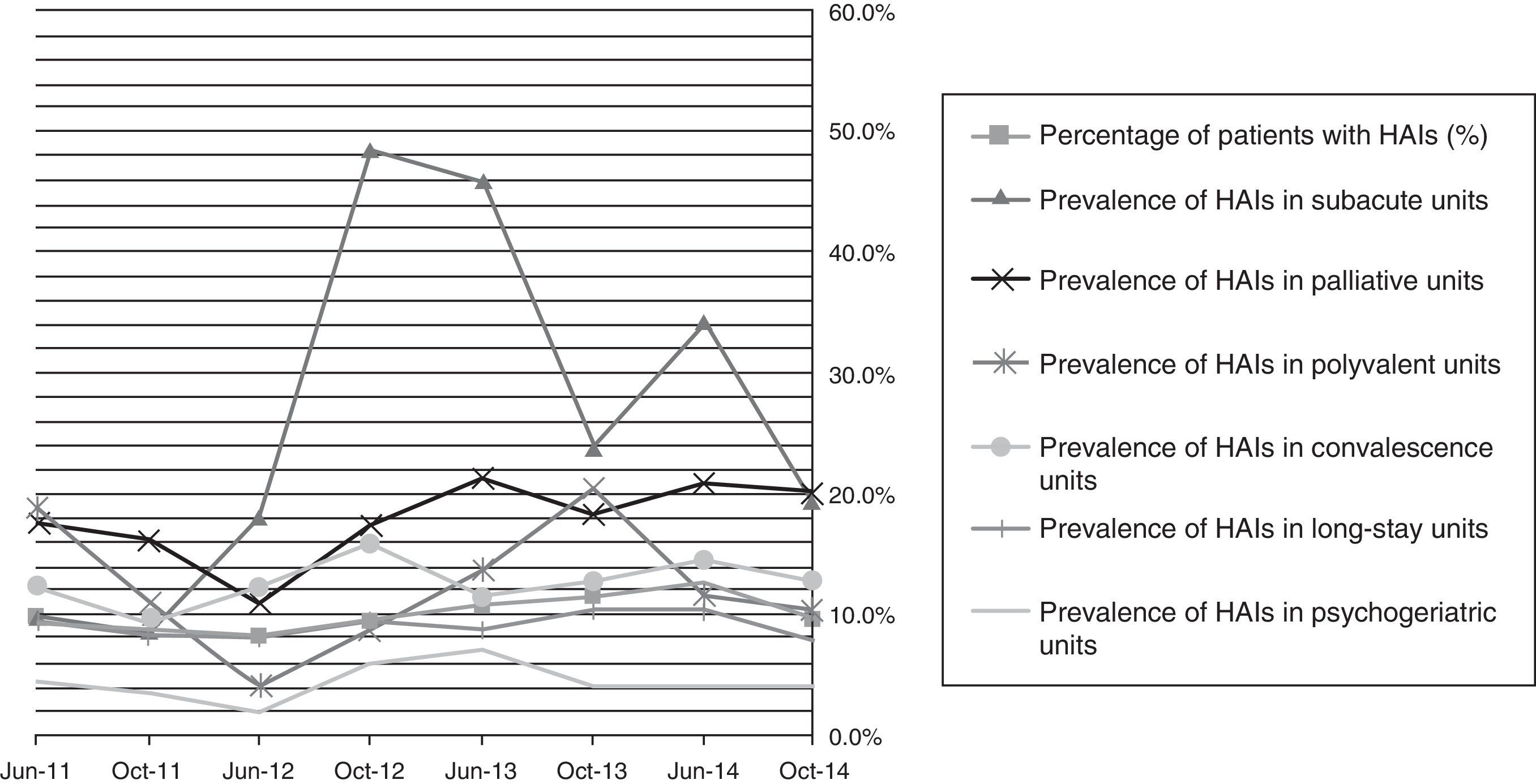

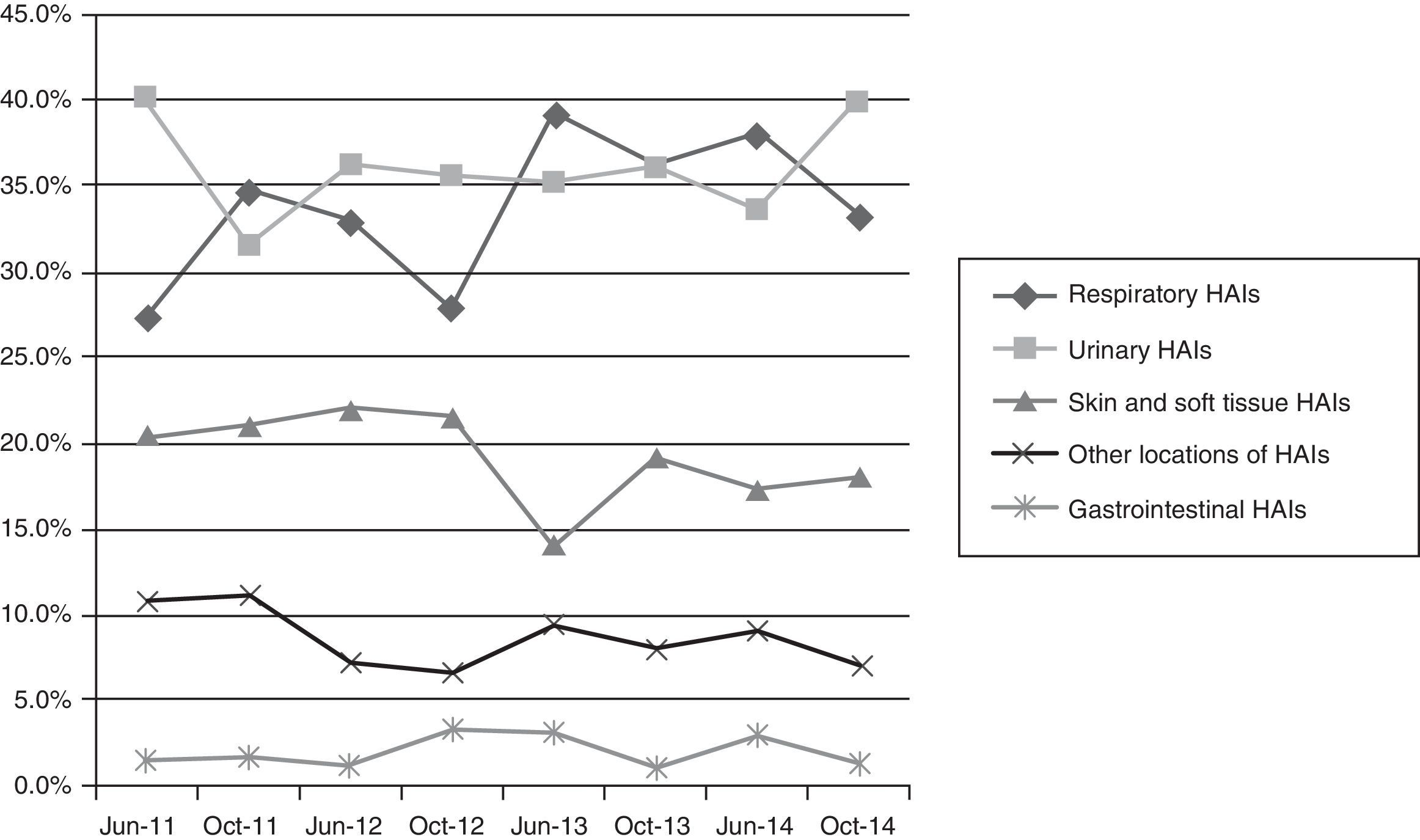

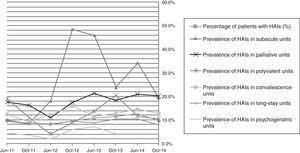

Prevalence of healthcare-associated infections in the long-term care facilities studiedThe prevalence of HAIs in the aggregate data was 10.2% (8.1–12.4%). The distribution by type of unit was highly diverse, with the sub-acute units (22.3%) and palliative care (18.7%) accumulating a higher percentage of infections. In the remaining units, the proportion of infections was 12.8% in polyvalent units, 11.7% in convalescence units, and 8.1% in long-term care units. The evolution of these data in the different prevalence sections is shown in Fig. 3.

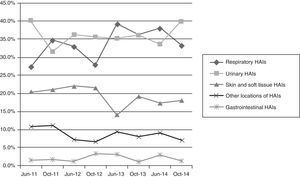

The types of infection were distributed similarly between respiratory infections (35.8%)—including both pneumonia and upper respiratory tract infections—and urinary infections (35.8%), followed by skin and soft tissue infections (17%) and other infections (10.5%)—including gastrointestinal infections (Fig. 4).

Prevalence of antibiotic use and multidrug-resistant micro-organismsAt the time of the study, 12% of patients were taking antibiotics. The most used antibiotics, globally, were amoxicillin/clavulanic acid (30%), ciprofloxacin (18%) and levofloxacin (8%). In 64% of cases these antibiotics were provided empirically, with no culture requested. The micro-organisms with resistance problems most frequently identified in LTCFs were extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing enterobacteriaceae, multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa and MRSA. No significant differences were observed in the pattern related to the type of site.

DiscussionThe overall prevalence of infections registered in our LTCFs is much higher than that published in the HALT study and in other international studies published previously.2,11 In all of them, just like in our study, the variability between sites is very high. The differences in types of patient admitted are the main cause of this variability. Thus in convalescent or sub-acute centres, patients are often in unstable situations and frequently receive antibiotics in a similar way to that in acute care centres, with this situation being that which is associated with a higher prevalence of infection. In the Registro de Infección Sociosanitaria-Lleida [Socio-Health Infection Registry-Lleida] (RISS Lleida)9 it was detected that up to 85% of patients had received some antibiotic treatment prior to their visit to the acute care units. Another main factor, which would explain the high percentage of infection, is that transfer to acute care units from LTCFs when a patient has an infection or any complication that does not require surgical intervention is becoming less common. A concerning piece of information from our study is the high prevalence of infection recorded in long-term care facilities in patients with fewer extrinsic risk factors. These figures, which seem to be very solid, considering the large number of patients included and the limited internal variability observed in the different sections addressed, are also much higher than those reported in similar populations in the majority of studies.

Similarly, the prevalence of antimicrobial use is also very high. This use, which is done mainly empirically, also contributes to the generation and subsequent spread of multidrug-resistant micro-organisms in healthcare facilities.12 The most important limitation of the study was the heterogeneity of the participating sites, which has given rise to very wide confidence intervals.

These results show the need to extend the strategies and patient safety programmes—specifically infection prevention programmes—to LTCFs, guaranteeing an adequate number of specialised staff members with sufficient dedicated time. It is necessary to continue delving into the study of preventative measures with greater cost-efficiency in these sites and, at the same time, to establish and disseminate some HAI prevention clinical guidelines in Spain based on the best clinical evidence available. Epidemiological surveillance should adapt to the characteristics of each site, with key aspects being the recording of colonised or infected patients and the coordination of health and social systems by using global control programmes.

FundingThe authors declare that they have no external sources of funding.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

VINCat Group:

Alex Smithson

Alonso Villaverde Amat

Angels Garcia Flores

Anna Besolí Codina

Anna Olivé i Torralba

Ana Valls Sastre

Begoña López Asensio

Benito J Fontecha Gómez

Carlina Peña Hernandez

Carme Puigdengoles Arnó

Carme Sala i Rovira

Carmen Sánchez Buendia

Carmen Santos Gallego

Carolina Peña Hernández

Charo Casas Floriano

Concepcion Cabanes Duran

Cristian Carrasquer Díaz

Cristina Garcia Fortea

Cristina Mayordomo Lacambra

Daniel Serra Giralt

David Arlandiz Puchol

Dolors Cubí Montanyà

Dolors Quera Ayma

Elena Moltó Llarena

Enric Ballarbriga Garcia

Esther Moreno Rubio

Esther Pallares Fernandez

Eulàlia Padró Roig

Evelyn Shaw Perujo

Ezequiel Martínez López

Gabriel de Febrer Martínez

Ignasi Coll Rolduà

Immaculada Grau Joaquim

Íngrid Bullich Marín

Inmaculada Fernández Moreno

Irene Moreno Moreno

Isabel Collado Perez

Ivan González Tejón

Joan Grané Alzina

Joan Manuel Pèrez-castejón Garrote

Joan Serra Moscoso

Joaquim Amoros Leroux

Jordi Borras Adam

Jose M Cuartero Olona

Jose Maria Peña Saez

Josefa Perez Martinez

Josep Vilaró Pujals

Lluis Espinosa Serralta

Lluis Tárraga Mestre

Luis Pujol Marti

Maria Carmen Gimenez Buendia

Maria Empar Riu Ventosa

Maria Lluisa Rocas Minella

Maria Nabal Vicuña

Mariola Domínguez González

Marisa Jofre Valls

Marta Ferrer Solà

M. Teresa Ros Prat

Mireia Bosch Fabregas

Natàlia Vallmajó Trayter

Neus Albanell Tortades

Núria Solà Segalà

Núria Comes Garcia

Oscar Ros Garrigós

Pau Sánchez Ferrin

Ramon Sellares Ribera

Ramón Torres LLuelles

Ricard Buitrago Figueres

Rocio Ibañez Avila

Rosa Navarro Ezquerra

Rosina Piquer Siré

Silvia Mirete Bara

Susana Subirats Alvarez

Teresa Vila i Subirana

Victoria Bonet Heras

A list of those who form part of the VINCat Group is found in Appendix 1 at the end of the article.

Please cite this article as: Serrano M, Barcenilla F, Limón E, Pujol M, Gudiol F, en representación del Grupo VINCat. Prevalencia de infección relacionada con la asistencia sanitaria en centros sanitarios de cuidados prolongados de Cataluña. Programa de Vigilancia de la Infección Nosocomial en Cataluña (VINCat). Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:503–508.