The objective of this study was to know the prevalence and clinical-epidemiological characteristics of patients with chronic infection due to hepatitis D virus (HDV).

Patients and methodsA retrospective descriptive study was carried out on patients with HDV infection under follow-up in a hospital in 2023. All patients carrying HBsAg were tested for antibodies against HDV. HDV RNA detection was performed in all antibody-positive samples. The medical records were reviewed.

ResultsOf the 340 patients carrying HBsAg, 24 (7.1%) had anti-HDV antibodies, and 6 (25%) had detectable HDV RNA (chronic infection). The prevalence of chronic hepatitis in HBsAg carriers was 1.8%. All patients had a genotype 1 infection. Half of the patients were of African origin and 29.2% were Spanish. Of the 6 patients with chronic infection, 5 (83.3%) had cirrhosis and 2 (33.3%) had hepatocellular carcinoma. Half of the patients had some exacerbation of the disease during follow-up. Of the 18 patients without viremia, 2 (11.1%) presented cirrhosis (one recently diagnosed). The mean follow-up time of patients without viremia was 13.5 years.

ConclusionsThe prevalence of chronic HDV hepatitis in our area is low and in all cases it presents as an advanced disease, with exacerbations during follow-up. Patients without viremia have probably resolved the infection, as viremia was not detected in any moment.

El objetivo del estudio fue conocer la prevalencia y las características clínico-epidemiológicas de los pacientes con infección crónica por el virus de la hepatitis D (VHD).

Pacientes y métodosSe realizó un estudio descriptivo retrospectivo de los pacientes con infección por VHD en seguimiento en un área de salud en el año 2023. A los pacientes portadores de HBsAg se les realizó la detección de anticuerpos frente al VHD. En todas las muestras positivas para anticuerpos se realizó la detección de ARN del VHD. Se revisaron las historias clínicas.

ResultadosDe los 340 pacientes portadores de HBsAg, 24 (7,1%) presentaban anticuerpos anti-VHD, y 6 (25%) presentaban ARN del VHD detectable (infección crónica). La prevalencia de infección crónica en portadores de HBsAg fue 1,8%. Todos los pacientes presentaron una infección por genotipo 1. La mitad de los pacientes eran de origen africano y el 29,2% españoles. De los seis pacientes con hepatitis, 5 (83,3%) presentaban cirrosis y 2 (33,3%) hepatocarcinoma. La mitad de los pacientes tuvieron alguna reagudización de la enfermedad durante el seguimiento. De los 18 pacientes sin viremia, 2 (11,1%) presentaron cirrosis (uno de reciente diagnóstico). El tiempo medio de seguimiento de los pacientes sin viremia fue de 13,5 años.

ConclusionesLa prevalencia de infección crónica por VHD en nuestro medio es baja y se presenta en todos los casos como una enfermedad avanzada, con reagudizaciones en el seguimiento. Los pacientes sin viremia probablemente hayan resuelto la infección, al no detectársele en ningún momento.

Hepatitis delta virus (HDV) is a defective virus that requires the hepatitis B virus surface antigen (HBsAg) for replication. HDV infection causes the most severe forms of viral hepatitis in adults. However, it is a forgotten disease whose real prevalence is unknown and for which there was no specific treatment until the recent approval of bulevirtide.

Several recent meta-analyses, based on studies carried out mainly in the 1980s and 1990s, estimated highly variable prevalences,1–3 although they all agree on the existence of geographical heterogeneity and that the burden of the disease is probably greater than estimated. This lack of knowledge is partly due to the fact that, although hepatitis B management guidelines recommend ruling out HDV infection in all HBsAg carriers,4 this is actually done in less than half of patients.5–7 In Spain, the last published seroprevalence study estimated that 7.7% of hepatitis B virus (HBV) carriers were infected by HDV.8 However, the prevalence of chronic hepatitis is unknown and, although estimated to be low, it is impossible to know how it may be affected by migration from countries where it is more endemic. The prevalence is currently high in Central Asia, the Amazon basin and sub-Saharan Africa.9 Due to the underdiagnosis of the disease and the lack of robust systems for its detection, we also have a lack of understanding about its behaviour and progression in our setting.10,11 Although HDV is known to cause liver disease with rapid progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma,12,13 there are studies suggesting that progression is variable and that a higher percentage than previously thought could have an indolent course.14

In order to determine the prevalence of chronic HDV infection and patient characteristics, we conducted a clinical-epidemiological study of the disease in our area.

Patients and methodsA retrospective descriptive clinical-epidemiological study of chronic HDV infection was conducted in a health area covering a population of approximately 350,000 inhabitants over 14 years of age on the island of Gran Canaria (Spain).

Patients. All patients under follow-up at our hospital’s Hepatology Unit in 2023 were included. In our area, all HBsAg carriers have been screened for HDV since 1990 by testing for specific antibodies in serum (reflex testing) and, since 2010, all patients with antibodies have had a PCR test to detect viral RNA (double reflex testing). All patients with HDV infection had RNA detection testing at each visit (once or twice a year).

HDV infection was defined by the presence of HDV antibodies with no viraemia detected, and chronic infection when HDV RNA was detected in serum.

In 2023, we reviewed the medical records of all patients and collected epidemiological data (gender, age, country of birth, HIV and HCV co-infection, risk factors associated with infection), lab test data and clinical data (degree of liver involvement, disease progression) and information about their treatment.

Antibody detection. This was performed by chemiluminescent immunoassay (LIAISON® XL Murex Anti-HDV Assay; Diasorin, Saluggia, Italy).

Detection of viral RNA. This was performed by reverse transcription PCR (Lightmix® kit Hepatitis D virus, TibMolBiol) after RNA extraction using the EasyMag® system (Biomerieux). From 2010 to 2014, a qualitative PCR was performed and from 2014 on, the viral load was quantified with the same PCR test, which is able to detect fewer than 10 copies/ml. All patients had viral load testing on at least one sample using two other commercially available quantification systems, validated for the quantification of all genotypes (Roboscreen® HDV RNA Quantification kit 2.0; Roboscreen Diagnostics and Hepatitis Delta RT-PCR system kit® Vircell), which are able to detect fewer than 10 copies/ml following the manufacturer’s recommendations.

Genotyping. This was performed by next-generation sequencing (NGS). A sequencing strategy based on near-full-length amplicons using overlapping primers was used.15 These amplicons were sequenced using Illumina technology and the resulting libraries were processed using the NextSeq 1000 system. For assembly, the CLC-Genomics-Workbench software, which uses reference sequences of various genotypes obtained from the hepatitis delta virus database, was used (https://hdvdb.bio.wzw.tum.de/hdvdb/).

Statistical analysis. Categorical variables were compared with the chi-square test and p-values<0.05 were considered statistically significant differences.

Ethical considerations. This study was approved by the Hospital Universitario de Gran Canaria Dr. Negrín Independent Ethics Committee for research with medicines (IECm Code 2024-055-1).

ResultsIn our area there were 444 patients diagnosed with chronic HBV infection, 25 (5.6%) of whom had HDV infection (prevalence: 7.1 per 100,000 population; 0.007%). Of the 444 patients, 340 (76.6%) were actively being followed up at the Hepatology Unit and 104 had not attended their appointments (one of them with HDV infection without viraemia). Of the 340 patients actually being followed up, 24 (7.1%) had antibodies against HDV, and out of these, viral RNA was detected in serum in six (25.0%). Viral RNA detection was performed in all patients, in at least one sample, with the three PCR techniques used, with complete concordance. In all cases, HDV infection was diagnosed at the same time as HBV, without being able to determine whether it was a co-infection or superinfection. The prevalence of chronic HDV infection among HBV carriers was 1.8% and the prevalence of diagnosed chronic infection in our population was 1.7 cases per 100,000. All patients with viraemia were typed and all had genotype 1 infection.

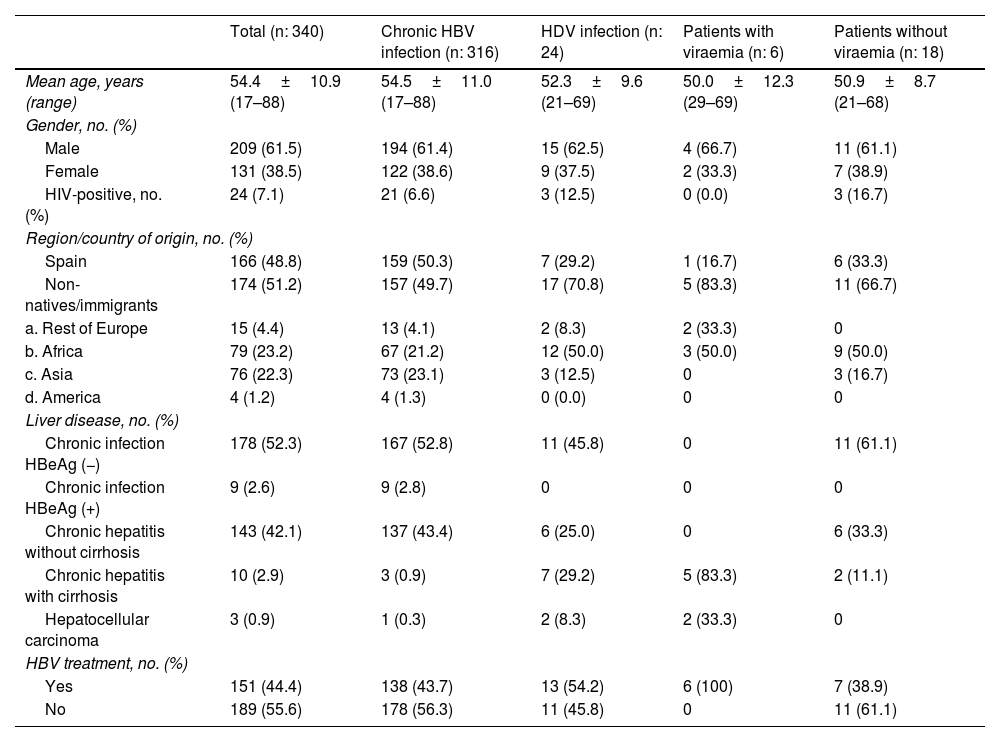

Table 1 compares the clinical-epidemiological characteristics of patients with chronic HBV infection and patients with HBV and HDV infection, differentiating between patients with and without viraemia. With regard to epidemiological characteristics, 15.2% of patients of African origin had HDV infection (91.7% sub-Saharan), compared to 4.2% of Spaniards and 3.9% of Asians (one from China, one from India and one from Pakistan). Of the seven Spanish patients, two had a history of drug addiction and in another two transmission was probably through family contact. In terms of clinical characteristics, 29.2% of patients with HDV infection had cirrhosis, compared to 0.9% of those infected by HBV alone (p<0.05).

Clinical-epidemiological characteristics of patients with chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection and chronic hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection, with and without viraemia.

| Total (n: 340) | Chronic HBV infection (n: 316) | HDV infection (n: 24) | Patients with viraemia (n: 6) | Patients without viraemia (n: 18) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age, years (range) | 54.4±10.9 (17–88) | 54.5±11.0 (17–88) | 52.3±9.6 (21–69) | 50.0±12.3 (29–69) | 50.9±8.7 (21–68) |

| Gender, no. (%) | |||||

| Male | 209 (61.5) | 194 (61.4) | 15 (62.5) | 4 (66.7) | 11 (61.1) |

| Female | 131 (38.5) | 122 (38.6) | 9 (37.5) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (38.9) |

| HIV-positive, no. (%) | 24 (7.1) | 21 (6.6) | 3 (12.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (16.7) |

| Region/country of origin, no. (%) | |||||

| Spain | 166 (48.8) | 159 (50.3) | 7 (29.2) | 1 (16.7) | 6 (33.3) |

| Non-natives/immigrants | 174 (51.2) | 157 (49.7) | 17 (70.8) | 5 (83.3) | 11 (66.7) |

| a. Rest of Europe | 15 (4.4) | 13 (4.1) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (33.3) | 0 |

| b. Africa | 79 (23.2) | 67 (21.2) | 12 (50.0) | 3 (50.0) | 9 (50.0) |

| c. Asia | 76 (22.3) | 73 (23.1) | 3 (12.5) | 0 | 3 (16.7) |

| d. America | 4 (1.2) | 4 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Liver disease, no. (%) | |||||

| Chronic infection HBeAg (−) | 178 (52.3) | 167 (52.8) | 11 (45.8) | 0 | 11 (61.1) |

| Chronic infection HBeAg (+) | 9 (2.6) | 9 (2.8) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Chronic hepatitis without cirrhosis | 143 (42.1) | 137 (43.4) | 6 (25.0) | 0 | 6 (33.3) |

| Chronic hepatitis with cirrhosis | 10 (2.9) | 3 (0.9) | 7 (29.2) | 5 (83.3) | 2 (11.1) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma | 3 (0.9) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (8.3) | 2 (33.3) | 0 |

| HBV treatment, no. (%) | |||||

| Yes | 151 (44.4) | 138 (43.7) | 13 (54.2) | 6 (100) | 7 (38.9) |

| No | 189 (55.6) | 178 (56.3) | 11 (45.8) | 0 | 11 (61.1) |

HBeAg: hepatitis B virus e-antigen.

Two patients with HDV infection without viraemia had cirrhosis; one had recently started antiviral treatment with entecavir and the other, of Indian origin, diagnosed and treated for HBV for more than 25 years, had sustained undetectable viral loads for both viruses, although his liver disease was progressing. The mean follow-up time of the 18 non-viraemic patients was 13.5±7.2 (range: 1–36) years; 61.1% had been followed up for more than 10 years at our hospital.

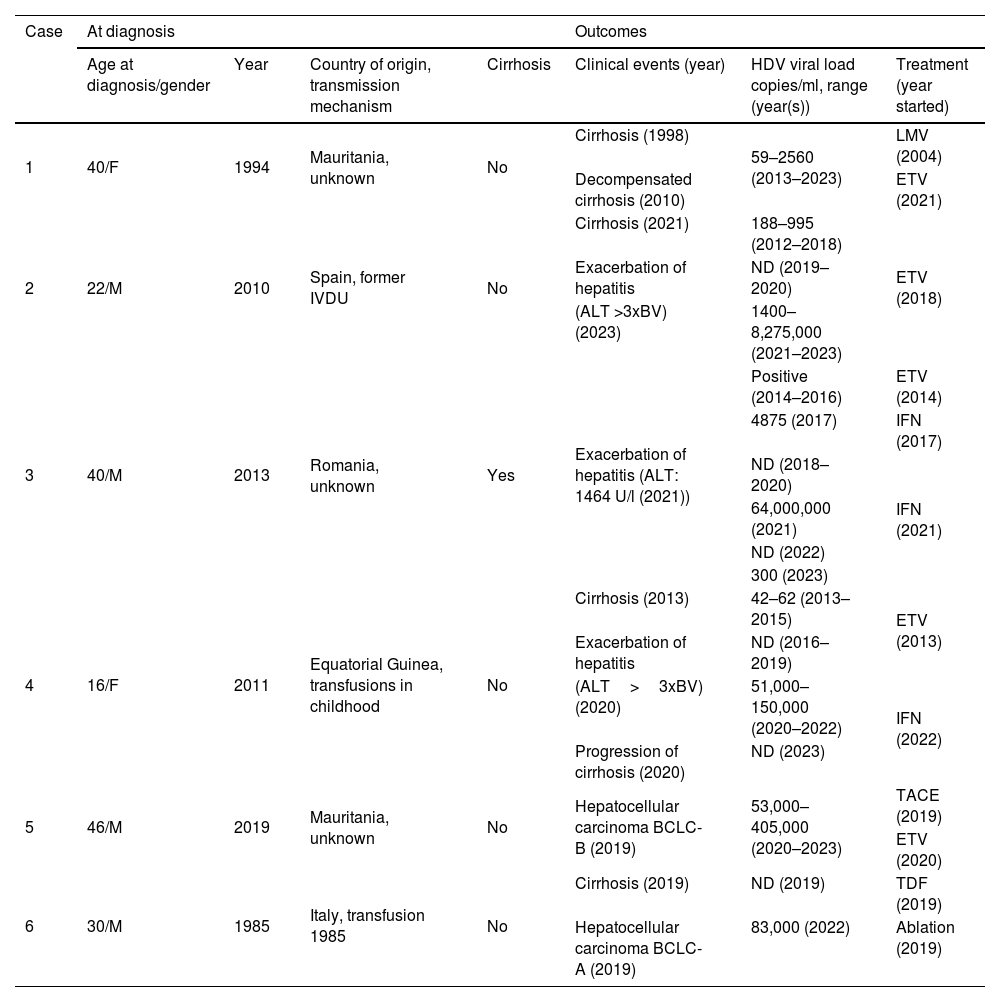

Table 2 shows the clinical outcomes of the six patients with chronic HDV infection. At the time of diagnosis, only one patient had cirrhosis and another had hepatocellular carcinoma. Despite receiving treatment for hepatitis B with virological response, liver disease worsened in all patients. The only candidate for liver transplant was patient 6, currently on the waiting list. None of the patients had co-infection with other hepatotropic viruses, or any condition that might promote fibrosis progression. During follow-up, the clinical condition of half of the viraemic patients worsened, with an increase in viral load and transaminases and progression of liver disease (patients 2, 3 and 4). Two patients (patients 3 and 4) received treatment with interferon (IFN). Patient 3 received two cycles of IFN for 48 weeks (one in 2017 and another in 2021), achieving negative results for viral RNA a few months after starting the treatment and maintaining this for more than a year after its withdrawal, but with a subsequent relapse. Patient 4 achieved resolution of the infection with negative HBsAg.

Clinical-epidemiological characteristics and outcomes for the six patients with chronic hepatitis D virus (HDV) infection.

| Case | At diagnosis | Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at diagnosis/gender | Year | Country of origin, transmission mechanism | Cirrhosis | Clinical events (year) | HDV viral load copies/ml, range (year(s)) | Treatment (year started) | |

| 1 | 40/F | 1994 | Mauritania, unknown | No | Cirrhosis (1998) | 59–2560 (2013–2023) | LMV (2004) |

| Decompensated cirrhosis (2010) | ETV (2021) | ||||||

| 2 | 22/M | 2010 | Spain, former IVDU | No | Cirrhosis (2021) | 188–995 (2012–2018) | ETV (2018) |

| Exacerbation of hepatitis | ND (2019–2020) | ||||||

| (ALT >3xBV) (2023) | 1400–8,275,000 (2021–2023) | ||||||

| 3 | 40/M | 2013 | Romania, unknown | Yes | Exacerbation of hepatitis (ALT: 1464 U/l (2021)) | Positive (2014–2016) | ETV (2014) |

| 4875 (2017) | IFN (2017) | ||||||

| ND (2018–2020) | IFN (2021) | ||||||

| 64,000,000 (2021) | |||||||

| ND (2022) | |||||||

| 300 (2023) | |||||||

| 4 | 16/F | 2011 | Equatorial Guinea, transfusions in childhood | No | Cirrhosis (2013) | 42–62 (2013–2015) | ETV (2013) |

| Exacerbation of hepatitis | ND (2016–2019) | ||||||

| (ALT>3xBV) (2020) | 51,000–150,000 (2020–2022) | IFN (2022) | |||||

| Progression of cirrhosis (2020) | ND (2023) | ||||||

| 5 | 46/M | 2019 | Mauritania, unknown | No | Hepatocellular carcinoma BCLC-B (2019) | 53,000–405,000 (2020–2023) | TACE (2019) |

| ETV (2020) | |||||||

| 6 | 30/M | 1985 | Italy, transfusion 1985 | No | Cirrhosis (2019) | ND (2019) | TDF (2019) |

| Hepatocellular carcinoma BCLC-A (2019) | 83,000 (2022) | Ablation (2019) | |||||

M: male; F: female; IVDU: intravenous drug user; ND: not detectable; BV: baseline value; TACE: transcatheter arterial chemoembolisation; LMV: lamivudine; ETV: entecavir; IFN: interferon; TDF: tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Hepatitis D is the most severe form of chronic viral hepatitis, with frequent progression to cirrhosis and hepatocellular carcinoma.16 Due to vaccination campaigns against HBV, the prevalence of hepatitis D has fallen, as younger generations are protected against HBV and therefore also against HDV.9 In Europe, HDV infection only remains endemic in some Eastern European countries.17 In Spain, in the few epidemiological studies published, a decrease in seroprevalence has been seen in recent years and a change in the epidemiology. The incidence has drastically fallen in drug addicts.18 However, immigration and sexual transmission are emerging as risk factors.19,20

In our study, the seroprevalence of HDV among HBsAg carriers was similar to that estimated in the national seroprevalence study,8 and the prevalence of chronic infection was 1.8%. This low prevalence is in line with expectations, due both to the reduction in transmission thanks to vaccination and to the heterogeneous progression of a disease for which, until now, transplantation was the only curative treatment; patients in whom the disease does not progress are expected to have low or undetectable viral loads, as has been reported in another study.21 Our study supports the low prevalence data, as for over 30 years, reflex testing has been performed on all HBsAg carriers. It is therefore to be expected that most of the patients we diagnose will come from endemic areas, where prevalence is high and vaccination coverage is low, or they will be patients who were infected over 30 years ago in whom the progression of the disease has been slow.

Very few longitudinal studies have analysed long-term outcomes in these patients, so the risk factors for poorer outcomes have not been fully identified, but they are known to include persistent viraemia and the genotype.12,21–24 Most of our patients who had antibodies but no viraemia did not have hepatitis. Nor did they have reactivation of viraemia at any time, despite a long follow-up, so it is most likely that their infection resolved spontaneously. However, all the patients with viraemia had advanced chronic liver disease, without clinical improvement. Only one patient without viraemia showed similar behaviour, with disease progression despite obtaining negative results for HBV DNA. Due to the limitations of the diagnostic tests, being standardised only for the detection of genotype 1, a false negative cannot be ruled out given that sensitivity could vary in infections with genotypes other than 1. Furthermore, most of the time, low-sensitivity PCR tests are used, where sensitivity and reproducibility, primarily in samples with low viraemia, could be affected. Reduced sensitivity could diagnose patients with low-load viraemia as non-viraemic or as having transient viraemia, as recently reported.25 In our study, transient viraemia always occurred in patients with low viral load values or when patients were receiving interferon treatment. We therefore believe that the use of sensitive quantitative PCR diagnostic tests should be a priority, enabling treatment to be indicated for all patients with replication. It is also necessary to develop and standardise tests that can determine the sensitivity of quantifying non-type 1 genotypes.

Over the course of follow-up, two patients who received interferon therapy achieved negative test results for viraemia, which continued for a few months after the treatment ended, but both then had relapses, consistent with the findings of other authors.26,27 Another patient, however, achieved resolution of the infection with negative results for HBsAg.

Our study has the limitations of being both a local and retrospective study. Multicentre studies with a larger number of patients may clarify the role of this infection in our setting. Furthermore, the use of more sensitive molecular tests for quantifying viraemia will help us understand the real burden of the disease and improve its management.

This study is of interest because, in our health area, reflex testing with detection of antibodies against HDV has been carried out on all HBV carriers for over 30 years and, for the last 13 years, PCR has also been performed in all cases. Moreover, we have performed viral load detection on at least one sample with three different PCR diagnostic tests in all patients, with very good concordance between tests. We can therefore conclude that in our health area there is a low prevalence of chronic HDV hepatitis, and that it presents as an advanced disease, with all patients belonging to established risk groups. Genotype 1 was detected in all cases. Currently, in the majority of the patients with HDV antibodies who show no evidence of viraemia, the infection has probably resolved. Guidelines have recently been published for the management of HDV infection.28 Although this disease is not very prevalent in our setting and does not pose a major public health problem, it is a serious health problem for affected patients. Although parenteral transmission is in decline, we are likely to see new cases associated mainly with migratory movements.

FundingThis study received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.