Meningitis is a rare cause of postpartum fever.1 In nosocomial infections, enterococci are frequently involved.1 Enterococcal meningitis (EM) is, however, an uncommon disease, accounting for only 0.3–4% of cases of bacterial meningitis,2 with E. faecalis being the species involved in the majority of cases.3

EM may develop as a complication of postoperative infections or by hematogenous spread. The most common predisposing factor for postoperative EM is the presence of cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) devices, whereas hematogenous EM mainly affects patients with severe underlying conditions, e.g., cardiovascular or pulmonary disease, chronic renal failure and diabetes.4 Rarely, E. faecalis can be directly inoculated by invasive procedures such as neuraxial anesthesia, either epidural or spinal.4

A 32-year-old secundigravida with a single non-complicated pregnancy attended our center for a check-up. Of note in her medical record were obesity (BMI: 37kg/m2) and hypothyroidism.

The patient was admitted for labor induction at 38+2 gestational weeks. A combined spinal and epidural anesthesia was offered and performed following antiseptic measures (the anesthesiologist wore a hat, gloves and a mask, and the patient's skin was prepared with iodopovidone). The procedure was difficult due to the patient's obesity and two attempts were needed. Six hours later, she delivered vaginally without complications. The epidural catheter was removed immediately after delivery.

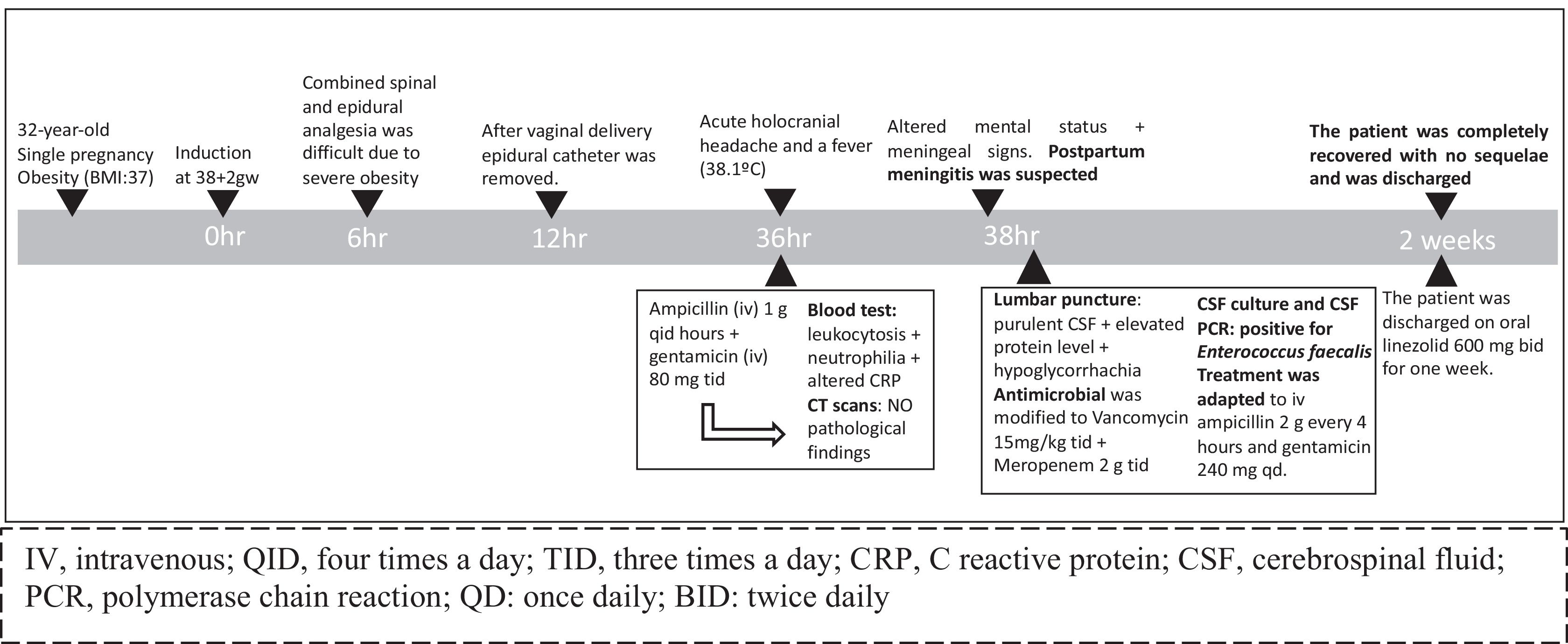

Almost 24h after delivery, the patient presented an acute holocranial headache, not alleviated by painkillers or postural measures, and a fever (38.1°C). The clinical examination was unremarkable. Blood cultures were performed, and intravenous (iv) ampicillin 1g qid and gentamicin 80mg tid were administrated empirically against a possible postpartum infection. Blood tests showed leukocytosis (15,400cells/ml) and mild neutrophilia. C-Reactive-Protein was 106.2mg/dl (NR<10). No other abnormalities were found. Cranial and abdominopelvic CT scans were unremarkable. Two hours later, the patient presented altered mental status and meningeal signs (Fig. 1). A lumbar puncture was performed immediately, revealing purulent CSF, pleocytosis (12,160cells/mL, NR<5cells/mL), hyperproteinorrachia (320.7mg/dL, NR<45mg/dL) and hypoglycorrhachia (1mg/dL, NR>50% of glycemia). The antimicrobial regimen was modified to iv vancomycin 15mg/kg tid and meropenem 2g tid. CSF culture and polymerase chain reaction were positive for E. faecalis. Blood cultures were also later positive for E. faecalis. Treatment was adapted to iv ampicillin 2g every 4h and gentamicin 240mg qid, resulting in clinical improvement over the following three days. After two weeks of treatment, the patient recovered completely without sequelae and was discharged on oral linezolid 600mg bid for one week.

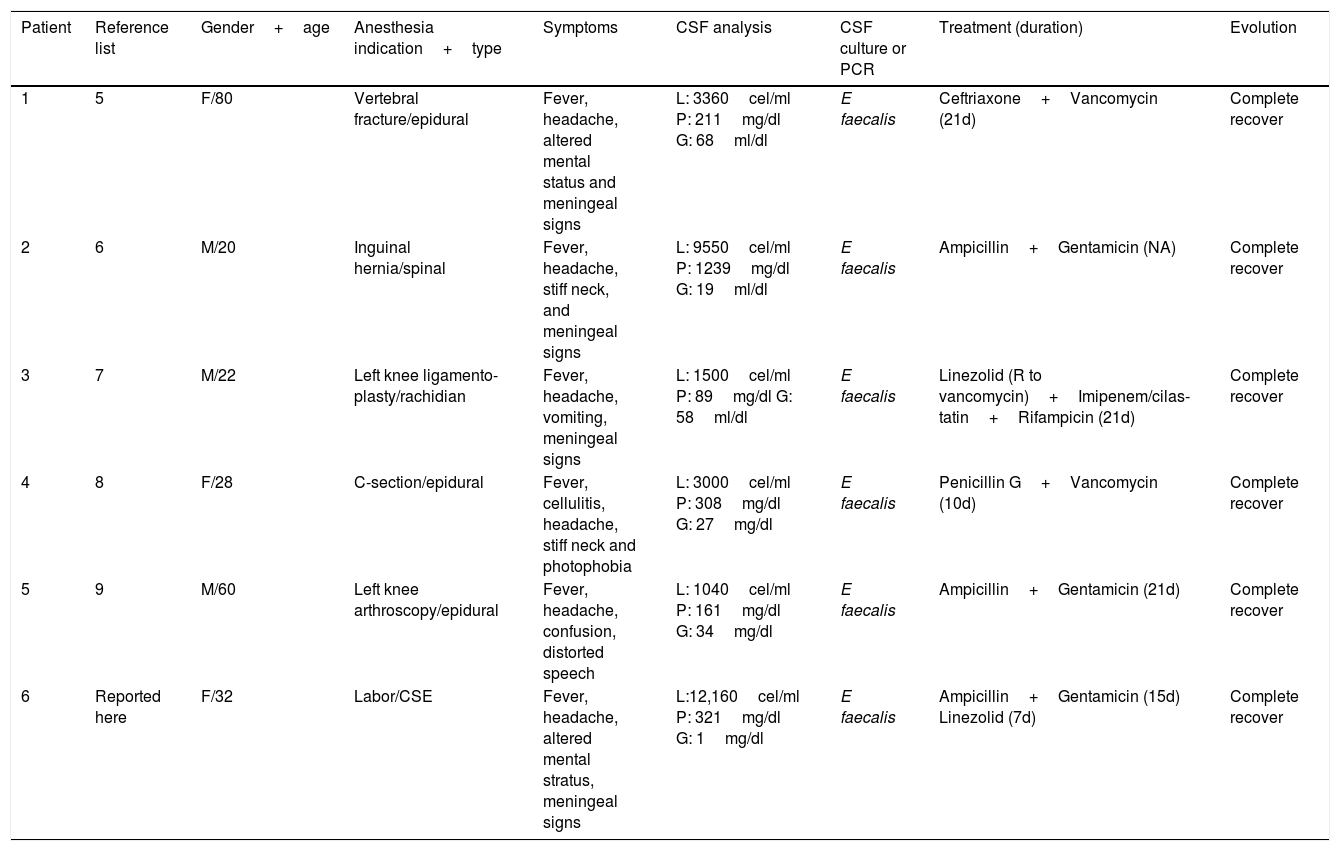

Although E. faecalis is a significant cause of nosocomial infections, meningitis is rare. Only six cases of EM related to neuraxial anesthesia, including ours, have been reported (Table 1),5–9 two of them following obstetric procedures. E. faecalis may be inoculated during catheter insertion from bacteria on the skin or may spread by hematogenous means from a distant infection or through the contamination of the fluids perfusing into the peridural or spinal space.3,4 In our case, despite following regular antiseptic measures for performing anesthesia, the procedure was difficult due to the patient's obesity. This condition may favor the inoculation of microbes into the CSF during catheter insertion. Moreover, there was no clinical condition or sign suggesting hematogenous spread from another source.

Reported cases of enterococcal meningitis secondary to neuraxial anesthesia.

| Patient | Reference list | Gender+age | Anesthesia indication+type | Symptoms | CSF analysis | CSF culture or PCR | Treatment (duration) | Evolution |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 | F/80 | Vertebral fracture/epidural | Fever, headache, altered mental status and meningeal signs | L: 3360cel/ml P: 211mg/dl G: 68ml/dl | E faecalis | Ceftriaxone+Vancomycin (21d) | Complete recover |

| 2 | 6 | M/20 | Inguinal hernia/spinal | Fever, headache, stiff neck, and meningeal signs | L: 9550cel/ml P: 1239mg/dl G: 19ml/dl | E faecalis | Ampicillin+Gentamicin (NA) | Complete recover |

| 3 | 7 | M/22 | Left knee ligamento-plasty/rachidian | Fever, headache, vomiting, meningeal signs | L: 1500cel/ml P: 89mg/dl G: 58ml/dl | E faecalis | Linezolid (R to vancomycin)+Imipenem/cilas-tatin+Rifampicin (21d) | Complete recover |

| 4 | 8 | F/28 | C-section/epidural | Fever, cellulitis, headache, stiff neck and photophobia | L: 3000cel/ml P: 308mg/dl G: 27mg/dl | E faecalis | Penicillin G+Vancomycin (10d) | Complete recover |

| 5 | 9 | M/60 | Left knee arthroscopy/epidural | Fever, headache, confusion, distorted speech | L: 1040cel/ml P: 161mg/dl G: 34mg/dl | E faecalis | Ampicillin+Gentamicin (21d) | Complete recover |

| 6 | Reported here | F/32 | Labor/CSE | Fever, headache, altered mental stratus, meningeal signs | L:12,160cel/ml P: 321mg/dl G: 1mg/dl | E faecalis | Ampicillin+Gentamicin (15d) Linezolid (7d) | Complete recover |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; F, female; M, male; L, leukocytes count; P, protein concentration; G, glucose concentration; R: resistance; CSE: combined spinal and epidural anesthesia; NA, not available.

International guidelines recommend antimicrobial therapy using combinations of cell-wall-active antibiotics and aminoglycosides that are synergistically effective against enterococci.2,10 Glycopeptides, e.g., vancomycin, have a lower CSF penetration and should be reserved for penicillin allergic patients and ampicillin-resistant strains.2 The duration of antimicrobial treatment has not been established, but most reports suggest 2–3 weeks.2 Additionally, enterococcus resistance is a growing problem worldwide.10

This is only the second case of postpartum meningitis due to E. faecalis reported so far. Although infrequent in the obstetric setting, acute meningitis is an infectious emergency requiring early diagnosis and treatment. It must be suspected in all cases of postpartum fever, particularly when headache is also present and not resolved with painkillers or/and postural measures. In obstetrical patients without a pathological medical history, neuraxial anesthesia during delivery may be a risk factor for bacterial meningitis where technically difficulties exist. Although data is limited, EM prognosis appears to favor a complete recovery without sequelae through antibiotic treatment. Preventing EM requires optimized antiseptic measures during neuraxial anesthesia administration.

FundingThese data have been generated as part of routine work in the laboratory and clinical consultation of the Hospital Dexeus University Hospital, Barcelona, Spain.

Conflict of interestNone to declare.

Under the auspices of the Càtedra d’ Investigació en Obstetrícia i Ginecologia de la Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona.