To establish the agent responsible for a gastroenteritis outbreak in a hotel in Menorca (Spain) in September 2016.

MethodsThe study included epidemiological and laboratory analysis. Environmental and stool samples were examined for bacterial and viral pathogens.

ResultsOne hundred and fifty-one cases were detected, 123 among the tourists staying in the hotel and 28 affecting the staff. The presence of genotype 2 norovirus was discovered in the microbiological studies of patient’s faeces, as well as in the surface samples of rooms and common areas. The control plan implemented allowed for control of the outbreak.

ConclusionsThis study on a genotype 2 norovirus outbreak reveals the importance of a rapid response for controlling these types of outbreaks.

Determinar el agente responsable de un brote de gastroenteritis ocurrido en un hotel de Menorca en septiembre de 2016.

MétodosSe estudió la epidemiología de los casos y se investigaron muestras ambientales y clínicas para la presencia de microorganismos indicadores y patógenos.

ResultadosSe detectaron 151 casos, 123 afectando a clientes y 28 a personal. Los análisis microbiológicos detectaron la presencia de norovirus genotipo II en heces de pacientes, así como en habitaciones y zonas comunes. El plan de control implementado permitió la erradicación del brote.

ConclusionesEste estudio del brote causado por norovirus del genotipo II demuestra que una rápida actuación es crítica para controlar este tipo de brotes.

Noroviruses are one of the main causes of gastroenteritis outbreaks worldwide, particularly in closed or semi-closed communities such as hospitals, cruise ships, hotels and prisons.1,2 Prevention and management of these outbreaks can be extremely difficult due to the characteristics of the pathogen, including a high viral load in faeces, which can last for several weeks after symptoms disappear,3 and a low infective dose.4 Moreover, it is a very stable virus in the environment and spreads through numerous routes of transmission, including water, food, surfaces, vomit and interpersonal transmission.5,6

On 12 September 2016, there was a report of a possible outbreak of gastroenteritis at a hotel on the island of Menorca (Balearic Islands, Spain). The objective of this study was to determine the aetiological agent of the outbreak and to implement appropriate management measures.

MethodsTo identify the possible aetiological agent and establish the most effective management measures, an epidemiological study was conducted. Data on demographics, symptoms, food and drink consumed, and other possible risk factors were collected by administering questionnaires. A case was defined as any person, whether a guest or an employee, in the hotel from 8 to 27 September 2016 with symptoms of diarrhoea, vomiting or abdominal pain.

Bacteriological analysis of environmental samples included food, drinking water, juices, ice and recreational waters. The following parameters were analysed in the food samples using internationally recognised techniques: total aerobic count, total lactose-positive Enterobacteriaceae, Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, Salmonella spp. and Listeria spp.7 In the samples of water for human consumption and juices, the total aerobic count was determined in plate count agar (PCA, Scharlab, Barcelona, Spain), and coliforms and Escherichia coli were determined using the Colilert® system (IDEXX, Maine, United States). Testing for Clostridium perfringens was also performed using membrane filtration.8 The ice and pool water samples were tested using the same system that was used to determine coliforms and Escherichia coli. The water and surface samples were tested for norovirus according to the method reported in the literature.9 For the water samples, a concentration was obtained through filtration prior to RNA purification.

The faeces samples were tested for intestinal pathogens, including the genera Salmonella, Shigella, Yersinia and Cryptosporidium, as previously reported.10 Testing for viruses was performed using Nadal® (Akralab, Alicante, Spain) immunological kits for rotaviruses, adenoviruses, enterovirus, astroviruses and noroviruses.

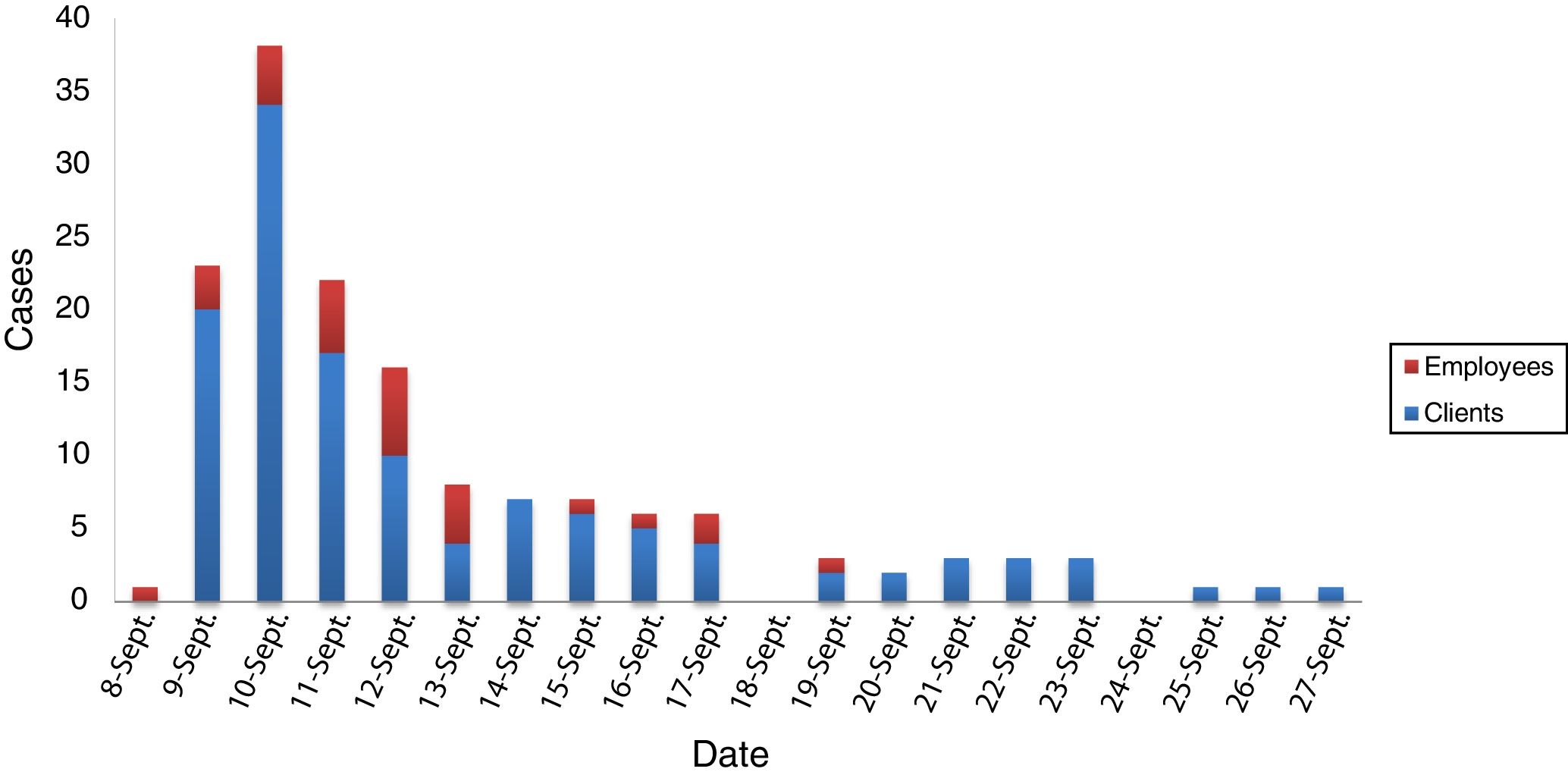

ResultsThe epidemiological study conducted at a hotel in Menorca that was the site of an outbreak of gastroenteritis in 2016 detected 151 cases: 123 guests and 28 employees (Fig. 1). The overall attack rate was 7.5%; the attack rate among the employees was higher than that among the guests (19.7% versus 6.6%). Although among the guests there was no clear difference by sex (56% of women versus 44% of men), among the employees, female staff were clearly affected more (78.6%). This was probably due to the fact that most of the employees responsible for cleaning the rooms of the affected guests were chambermaids. Regarding patient age, nearly half (48.8%) were 20–49 years old, followed by those over 50 (21.6%), those under 5 (18.40%) and finally those 5–19 years old (11.2%). The most common symptoms were vomiting (93.4%), abdominal pain (90.1%) and headache (72.8%). Symptoms of diarrhoea (50.3%) and fever (11.9%) were less commonly seen. Symptoms lasted one to three days, and in most cases were self-limiting. It should be noted that 6 cases required hospital treatment due to dehydration and were discharged in 24 h. Fig. 1 shows the epidemiological curve, with the first case of an affected employee on 8 September, then by a significant peak in the next few days and a gradual decline following implementation of management measures The last case was reported on 27 September.

Microbiological testing for determining the aetiological agent were performed on clinical and environmental samples, as reported in previous studies.10,11 The only two faeces samples available came from the two hospitalised cases. They were analysed by stool culture which found intestinal saprophytic microbiota but did not detect any bacterial pathogen. The virus test detected norovirus in one of the two samples. Testing of 6 food samples, 10 drinking water and pool water samples, and 2 ice samples did not detect pathogens. Testing also included samples taken from 6 surfaces in some of the patients' bedrooms and common areas (before and after cleaning). This testing detected norovirus genogroup II in one of the bedrooms prior to cleaning; the rest of the samples were negative.

As soon as it was suspected that the aetiological agent could be norovirus, a specific management plan was established. This management plan included increasing the frequency of cleaning in common areas such as foyers, the game room and the gym, in particular of anything that could come into contact with hands. Explicit mention was made of the lift and vending machine buttons, desks with leaflets, publicity brochures, activity leaflets, windows with children's hand prints in internal areas, etc. The restaurant also took immediate action, making hand sanitisers available at the entrance, covering the cutlery and replacing bread loaves and unpeeled fruits with pre-sliced bread and chopped fruit prepared and covered in advance. Brooms and vacuum cleaners were replaced with mops to avoid the airborne spread of the virus. High-pressure steam cleaners were acquired to deactivate the virus on textiles such as curtains and carpets. Surfaces in contact with the hands were treated with a 1% aqueous solution of Virkon® disinfectant (JohnsonDiversey, Spain), while the areas where episodes of vomiting took place were sprayed with a 0.25% aqueous solution. The remaining surfaces were treated with bleach or 70% alcohol, depending on the nature of the surface. Exclusive cleaning materials were used in the bedrooms of the affected guests, with special attention paid to door handles, taps, telephone keypads, remote controls and other frequently handled objects. Cleaning staff wore masks and gloves at all times, and used closed bags to dispose of vomit.

DiscussionThis study reports an outbreak of gastroenteritis caused by norovirus at a hotel. This pathogen was detected in half of faeces samples from patients; no other enteric pathogen was detected. In addition, its presence was also detected in environmental samples. These results demonstrate that norovirus was the aetiological agent of the outbreak.

The most likely scenario is that the employee who fell sick on 8 September brought the pathogen into the hotel, whereupon it rapidly spread among the staff and guests. The management measures implemented on 12 September reduced the number of cases, disappearing on 18 September. However, in the early hours of the morning on 18 September, a guest vomited in the hotel foyer and, curiously, the next day, new cases appeared. These cases were eventually brought under control; the last case appeared on 27 September. The vomit was probably the cause of the new wave of the outbreak, although thanks to the management measures that had already been implemented, this second wave was much more limited.

In Spain, outbreaks of norovirus have been reported in closed spaces such as hospitals,12,13 hotels10 and boarding schools,14 where interpersonal transmission has been shown to be a key factor. In this study, this route of transmission also seems to have played an essential role, since cases of patients who were related (members of the same family or group) were common during the outbreak.

In summary, the epidemiological data, microbiological testing and absence of other pathogens confirmed that the outbreak was caused by norovirus genogroup II. Fortunately, the implementation of appropriate management measures allowed the outbreak to be managed.

FundingThis study has received no specific funding from public, private or non-profit organisations.

Conflicts of interestNone.

Please cite this article as: Doménech-Sánchez A, Laso E, Genestar E, Berrocal CI. Brote de gastroenteritis causado por norovirus en un hotel de Menorca, España. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:22–24.