This study describes a mumps outbreak among a group of young people who shared a same narghile to smoking. Saliva and blood samples were obtained from 3 cases for RT-PCR and serology respectively.

MethodsThe notification of a mumps case started an epidemiological investigation. Information of other 6 additional symptomatic persons who had gathered with the case in a discotheque where they smoking in a same narghile was achieved. RT-PCR positive samples were genotyped by sequencing.

ResultsThe 7 patients resided in 3 different municipalities, and they do not have get together for more than a month until the meeting in the discotheque. Four cases were confirmed by RT-PCR and/or IgM determinations. The genomic investigation showed identical nucleic sequences.

ConclusionsThis outbreak is consequence of the common use of a narghile to smoking. The public usage of these water pipes should be regulated.

En este estudio se describe un brote de parotiditis que afectó a un grupo de jóvenes que compartieron un narguile para fumar.

MétodosLa notificación de un caso de parotiditis dio lugar a una investigación epidemiológica. Se recabó información de otras 6 personas sintomáticas que se habían reunido en una discoteca en la que habían fumado en un mismo narguile. Se obtuvieron muestras de saliva para RT-PCR y sangre para serología de parotiditis de otros 3 de estos casos. Las muestras RT-PCR positivas se genotipificaron por secuenciación.

ResultadosLos 7 pacientes residían en 3 municipios diferentes. Hacía más de un mes que no habían coincidido hasta que estuvieron en la discoteca. Cuatro casos se confirmaron por RT-PCR o IgM específica. La investigación genómica mostró secuencias idénticas.

ConclusionesEste brote es consecuencia de un uso compartido de un narguile. Consideramos que se debería regular la utilización pública de estas pipas.

The shared use of waterpipes (shisha, narguile, hookah) for smoking has become common in recent years, particularly among young people. In addition to tobacco-related harmful effects, it is also not without its own health risks.1 For example, infection transmission between users of a single waterpipe has been reported.2 Mumps or epidemic parotitis (EP), caused by a virus of the family Paramyxoviridae, is usually transmitted by direct contact or aerosol transmission, but it can also be spread by contaminated fomites.3 This study describes an outbreak of mumps in a group of young people who all smoked from the same waterpipe.

MethodsOn 26 April 2018, the Regional Public Health Laboratory of the Community of Madrid (LRSP-CM) reported to the Epidemiology Section of Móstoles (Community of Madrid) a reverse transcription polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) result positive to the mumps virus in the saliva of a 22-year-old male. The patient's doctor simultaneously reported that, according to the patient himself, some of his friends also had symptoms consistent with mumps. An epidemiological investigation was launched to confirm the existence of an outbreak, its extent and its characteristics, and to apply any control measures that may be necessary. The mumps case was contacted to gather information about the other people potentially infected. The patient mentioned six friends who he met in a nightclub in Madrid on the night of 28–29 March 2018. All smoked from the same waterpipe owned by the establishment. All those affected were interviewed to gather basic demographic and clinical information, as well as their medical histories of mumps vaccination. They were also asked about the times they had been with the rest of those affected in the last two months and if they remembered any contact with someone with mumps. The clinical information, results of the diagnostic tests and histories of prior vaccinations were compared against the corresponding records and the vaccination IT system of the Community of Madrid.

In addition to the already diagnosed case, saliva samples for RT-PCR and mumps IgM and IgG serology samples were collected from a further three cases, which were also analysed by the LRSP-CM. A real-time RT-PCR was used for gene amplification (Liferiver™ Mumps Virus Real Time RT-PCR Kit, Shanghai ZJ Bio-Tech Co., Ltd. Shanghai, China). Specific IgM and IgG serological testing was performed by ELISA (Enzygnost, Siemens, Germany). A serological analysis was conducted on one additional patient by the hospital at which he was treated. The RT-PCR-positive saliva samples were characterised at the National Microbiology Centre by sequencing the small hydrophobic protein gene (SH)4 and two other hypervariable non-coding regions of the mumps virus genome located between the coding regions of the N–P and M–F genes5. Saliva samples that were RT-PCR-positive to the mumps virus, and serology samples that were IgM-positive to the mumps virus were classified as confirmed cases, while the rest were deemed probable cases.6

Madrid’s Municipal Department of Public Health was informed of the outbreak in order to investigate the conditions of the establishment involved and of the waterpipes for customer use, as well as its maintenance and cleaning protocols.

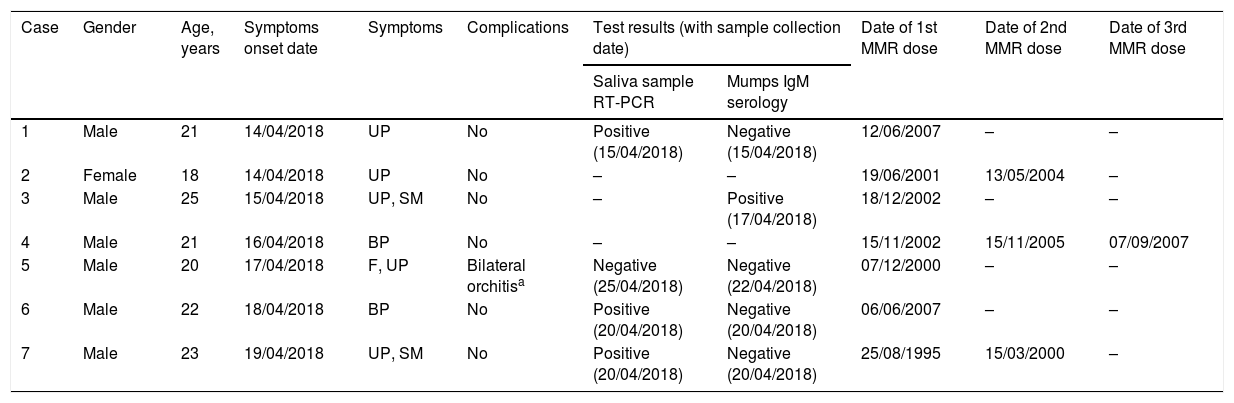

ResultsThe seven mumps cases required medical attention (four in hospital and three in primary care centres). The cases are described in Table 1. Four were classified as confirmed and three as probable. All had been vaccinated against mumps and the median time elapsed since the last vaccine dose received was 13 years. The patients lived in three different municipalities. None remembered any recent contact with anyone with mumps. Six of the cases were friends, but prior to meeting in the nightclub they had not all been together for more than a month and had not met again since. The other patient reported that he only knew one of the other members of the group, and it was he who had invited him to the nightclub. He had not had further contact with them since. All those affected smoked from the same waterpipe provided by the nightclub.

Description of the mumps cases.

| Case | Gender | Age, years | Symptoms onset date | Symptoms | Complications | Test results (with sample collection date) | Date of 1st MMR dose | Date of 2nd MMR dose | Date of 3rd MMR dose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Saliva sample RT-PCR | Mumps IgM serology | |||||||||

| 1 | Male | 21 | 14/04/2018 | UP | No | Positive (15/04/2018) | Negative (15/04/2018) | 12/06/2007 | – | – |

| 2 | Female | 18 | 14/04/2018 | UP | No | – | – | 19/06/2001 | 13/05/2004 | – |

| 3 | Male | 25 | 15/04/2018 | UP, SM | No | – | Positive (17/04/2018) | 18/12/2002 | – | – |

| 4 | Male | 21 | 16/04/2018 | BP | No | – | – | 15/11/2002 | 15/11/2005 | 07/09/2007 |

| 5 | Male | 20 | 17/04/2018 | F, UP | Bilateral orchitisa | Negative (25/04/2018) | Negative (22/04/2018) | 07/12/2000 | – | – |

| 6 | Male | 22 | 18/04/2018 | BP | No | Positive (20/04/2018) | Negative (20/04/2018) | 06/06/2007 | – | – |

| 7 | Male | 23 | 19/04/2018 | UP, SM | No | Positive (20/04/2018) | Negative (20/04/2018) | 25/08/1995 | 15/03/2000 | – |

BP: bilateral parotid swelling; F: fever; MMR: measles, mumps and rubella vaccine; SM: submaxillary gland swelling; UP: unilateral parotid swelling.

The genomic investigation of the RT-PCR-positive saliva samples showed identical SH sequences belonging to the variant MuVs/Madrid.ESP/50.16/2 of genotype G. Sequencing of the hypervariable regions of the mumps virus genome—N–P NCR and M–F NCR—also yielded the same result for the samples analysed.

The municipal inspection of the nightclub revealed that the establishment had several waterpipes and that the single-use disposable mouthpieces were packaged and sealed. The establishment had no written disinfection procedure for the pipes themselves or for the base of the waterpipes. The pipes were cleaned with alcohol and then washed under running water, while the base of the waterpipe was rinsed with water and cleaned with designated cylindrical brushes. No samples for microbiological analysis were collected from the waterpipes or their accessories.

DiscussionA mumps outbreak affecting a group of seven young adults who went to a nightclub and smoked from the same waterpipe was reported. These people, who live in different places, were only all together at the nightclub. As well as the time and place coinciding, the mumps virus strain was also found to be identical in three of the four cases analysed; for the other case, the sample was taken eight days after the onset of symptoms, which could explain the negative RT-PCR result.7 The mumps IgM serology result was only positive in one of the five cases in which it was tested. However, although IgM detection is considered a mumps marker, its sensitivity in vaccinated individuals is poor.8

Waterpipes for public use have been shown to harbour multiple microorganisms.9–11 The presence and transmission of the mumps virus by fomites of this kind is plausible.12 Moreover, the nightclub inspection found that there was no standardised procedure for waterpipe disinfection after use. No disinfectant was used to clean the base of the waterpipes. In terms of immunoprotection, although all cases had received at least one dose of the mumps vaccine, the time elapsed since the last vaccination received was at least 10 years. The protection conferred by the mumps vaccine has been shown to decrease over time13 and outbreaks among vaccinated individuals are not uncommon.14 Infection transmission between the members of the group seems highly unlikely. All cases experienced symptoms within five days of each other, which rules out the possibility that one member of the group may have infected the rest (the mumps virus incubation period is 12–25 days).15

The outbreak described above was caused by the shared use of a waterpipe, a behaviour that could not be consciously perceived by those affected as an unhealthy activity in the context of the "old normal" prior to the COVID-19 pandemic. The new social habits adopted after this pandemic could very possibly reduce these types of risk in the future.

This study has some limitations. Direct infection from someone else in the nightclub outside of the studied group cannot be ruled out. It would be reasonable to assume that such a highly infectious individual would have infected multiple people. Yet no other cases in connection with the nightclub were reported in the subsequent days. Another limitation is that the virological contamination of the waterpipes was not investigated. However, in light of the epidemiological data, it is very likely that the source of the outbreak was a contaminated waterpipe. We believe that the use of devices such as waterpipes should be regulated by law and we advocate waterpipe disinfection measures in public establishments11 (particularly in the context of other new infections, such as COVID-19).

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest. They further declare that they had no source of funding for the preparation of this manuscript.

With thanks to Marcos Alonso García of the Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón Preventive Medicine Department for reviewing the manuscript.

Please cite this article as: Aragón A, Velasco MJ, Gavilán AM, Fernández-García A, Sanz JC. Brote de parotiditis relacionado con el fumar en un narguile de uso público. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:503–505.