A previously healthy 5-month-old boy vaccinated according to the official vaccination schedule (including the 23-valent pneumococcal vaccine) was admitted to the paediatric intensive care unit with symptoms of sepsis and generalised seizures. A lumbar puncture was performed, which showed fluid compatible with bacterial meningitis (1200 leukocytes, 80% neutrophils, glucose 2mg/dl and proteins 2g/dl), and Gram-positive diplococci was observed on the Gram stain. Antibiotic treatment was started with cefotaxime (300mg/kg/day) and vancomycin (60mg/kg/day). Penicillin-sensitive Streptococcus pneumoniae (MIC 0.008μg/ml) and cefotaxime (MIC 0.012μg/ml) were isolated in the blood and cerebrospinal fluid and were later identified as serotype 15C, which is not included in the vaccine.

24h after initiating treatment, the infant was afebrile, with improved general condition and level of consciousness. Vancomycin was suspended. On the third day, the patient deteriorated and seizures reappeared. A cranial CT scan was performed that revealed ventricular enlargement and frontal effusions. An external ventricular drain was placed, which was replaced 3 days later due to obstruction. The infant improved slowly but on the twelfth day of admission he presented sudden deterioration with decreased level of consciousness, abnormal movements, pupillary changes, abnormal heart rate and increased blood flow due to the ventricular drain.

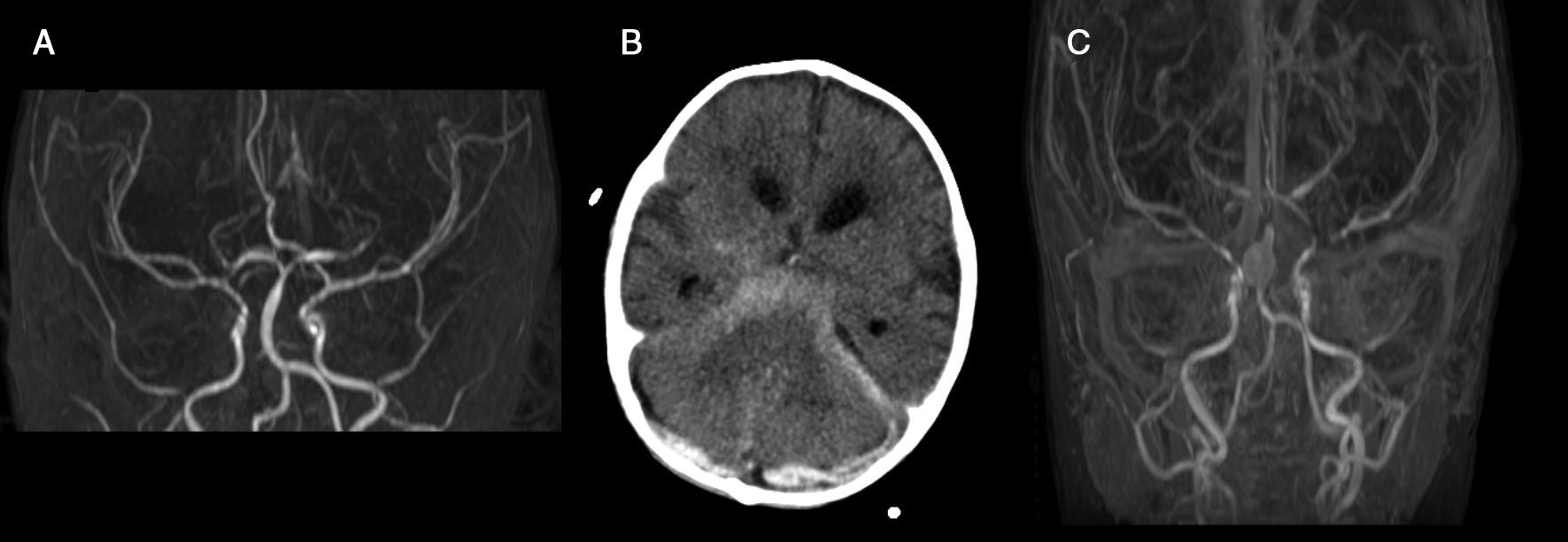

A new cranial CT scan was performed, which revealed ventricular and subarachnoid haemorrhage. With a suspected ruptured aneurysm, an angiography and magnetic resonance angiogram were performed. These tests confirmed the diagnosis of haemorrhage due to ruptured mycotic aneurysm of the basilar artery and multiple stenosis of most of the cerebral arteries studied (Fig. 1). The patient was not eligible for surgery and it was not possible to embolise the aneurysm due to a lack of collateral circulation. As such, life support was withdrawn and the patient died.

The term “mycotic” aneurysm was coined by Osler in 1885 to describe a mushroom-shaped aneurysm in subacute endocarditis.1 Although some authors use the term “mycotic” to describe infected aneurysms of any aetiology, most limit use of this term to aneurysms that form when material from a distant site causes infection of the vascular wall and subsequent dilation.2

The pathogenic mechanism includes septic emboli that occlude the vasa vasorum, contiguous spread of infection from other foci of infection, haematogenous infection of the tunica intima or damage to the arterial wall caused by surgery or vascular devices.3

Subarachnoid haemorrhage secondary to a ruptured aneurysm is the most common cause of spontaneous subarachnoid haemorrhage in children. However, a recent review by Garg et al. found that out of 62 children with intracranial aneurysms, only 2 were mycotic.4 Published cases of mycotic aneurysms in infants under the age of 1 year are extremely rare. In children, most mycotic aneurysms occur in the context of endocarditis, underlying vascular malformations, connective tissue disease or iatrogenesis, such as neonates with umbilical catheters.5

Before the advent of antibiotics, Streptococcus pneumoniae was a common cause of aneurysm infection. Although this fell dramatically with the arrival of penicillin, it may once again be an emerging pathogen in infected aneurysm.6,7 In a review of the literature, we found 23 published cases of aneurysms (mycotic and infected) caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, all of which were located in the aorta and in adults. We only found one case of a 65-year-old woman who was admitted for pneumococcal meningitis and died one week later due to a ruptured mycotic aneurysm.8

There is one published case of mycotic aneurysm and subarachnoid haemorrhage following tuberculous meningitis in an infant with congenital cytomegalovirus infection, in whom the vessels at the base of the cranium surrounded by inflammatory exudate developed infiltrative lesions. The granulomatous process in the subarachnoid space weakens and destroys the middle cerebral artery, causing aneurysmatic dilatation of the artery.9

This is the first case of pneumococcal intracranial mycotic aneurysm reported in the literature in infants.

The most important factor to consider in terms of treatment is aneurysm rupture.10 Unruptured aneurysms can only be treated with antibiotics, whereas ruptured aneurysms must be treated with antibiotics and surgery. Endovascular techniques may be useful in patients with ruptured infected aneurysms to contain the rupture until surgical treatment is viable.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Palacios A, Llorente AM, Ordóñez O, Martínez de Aragón A. Aneurisma micótico intracraneal en lactante con meningitis neumocócica. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:267–269.