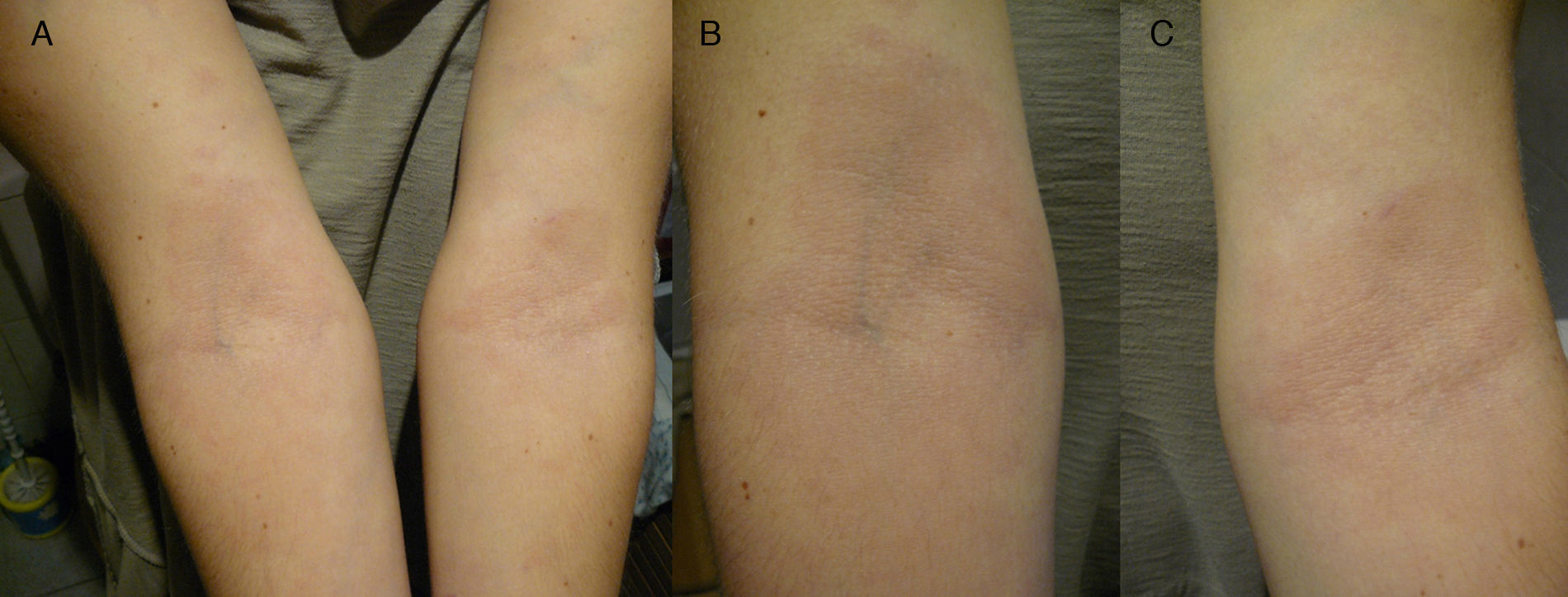

Spanish woman aged 44 who, in May 2011, went to the dermatologist with 2 hypochromic macules with slightly erythematous borders, on both forearms, showing centrifugal spread, but no signs of altered sensitivity or pruritus (Fig. 1). The patient went to the dermatologist and was diagnosed with eczema and treated with hydrocortisone. At that time, histopathology was ordered and, upon microscopic examination, epidermal atrophy with orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis and the presence of a small infundibular plug was observed. Vacuolar degeneration of the basal layer with some necrotic keratinocytes. Abundant interstitial mucin deposits were observed in the dermis. Some lymphocytes and plasma cells with superficial perivascular distribution. Isolated melanophages. Using PAS staining, 2 small fungal spores were observed on the surface of the keratin laminae. The final laboratory diagnosis was: compatible with lupus, with presence of surface fungi. The antinuclear antibody test (Anti-Ro/SSA) was negative. The patient was then treated for 2 months with itraconazole 400mg/day.

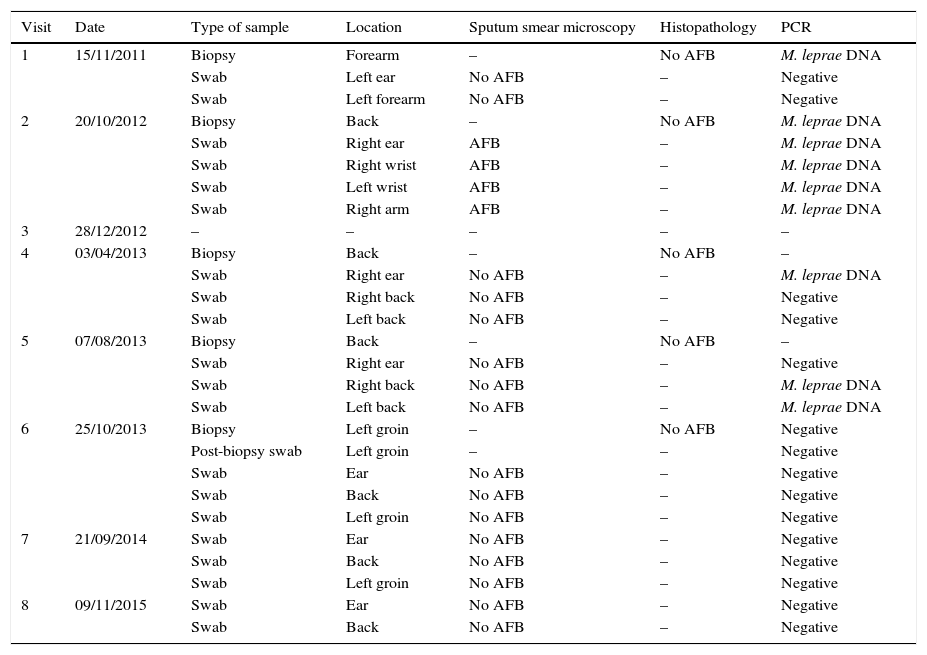

Clinical outcomeThe patient visited Sanatorio Fontilles in November 2011 (visit 1). At that time, both forearms still showed hypochromic lesions with slightly erythematous borders, with no alteration in sensitivity. No pathological history of interest, except that she lived in Calcutta (India) between 1996 and 1999 where she worked as a nurse in a leper colony treating active leprosy patients. Two lymph samples (left ear lobe and edge of an active lesion [left forearm]) were taken for microscopic examination (Ziehl-Neelsen) along with a forearm biopsy.1 The biopsy was divided into 2 parts: one half was fixed in 10% formalin (histopathology) and the other was fixed in 70% ethanol (molecular assays; PCR). No acid-fast bacilli (AFB) were observed in either sputum smear microscopy and anatomical pathology testing was non-specific (limited changes in spongiocytes and limited basal pigmentation), which is compatible with pityriasis alba without AFB. PCR was performed at the same time on DNA obtained from the lymph samples (swab),1,2 and no amplification of Mycobacterium leprae (M. leprae) DNA was observed in the samples (Table 1). However, amplification of M. leprae DNA was observed in the sample of DNA obtained from the skin biopsy. As no conclusive symptoms were observed and based on histopathology criteria, the doctors decided not to administer treatment.

Tests performed on the patient at Sanatorio Fontilles.

| Visit | Date | Type of sample | Location | Sputum smear microscopy | Histopathology | PCR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15/11/2011 | Biopsy | Forearm | – | No AFB | M. leprae DNA |

| Swab | Left ear | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Left forearm | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| 2 | 20/10/2012 | Biopsy | Back | – | No AFB | M. leprae DNA |

| Swab | Right ear | AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| Swab | Right wrist | AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| Swab | Left wrist | AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| Swab | Right arm | AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| 3 | 28/12/2012 | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4 | 03/04/2013 | Biopsy | Back | – | No AFB | – |

| Swab | Right ear | No AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| Swab | Right back | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Left back | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| 5 | 07/08/2013 | Biopsy | Back | – | No AFB | – |

| Swab | Right ear | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Right back | No AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| Swab | Left back | No AFB | – | M. leprae DNA | ||

| 6 | 25/10/2013 | Biopsy | Left groin | – | No AFB | Negative |

| Post-biopsy swab | Left groin | – | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Ear | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Back | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Left groin | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| 7 | 21/09/2014 | Swab | Ear | No AFB | – | Negative |

| Swab | Back | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| Swab | Left groin | No AFB | – | Negative | ||

| 8 | 09/11/2015 | Swab | Ear | No AFB | – | Negative |

| Swab | Back | No AFB | – | Negative |

AFB: acid-fast bacilli (Ziehl-Neelsen); M. leprae DNA: amplification of target fragment of M. leprae DNA detected; Negative: no amplification detected in PCR; –: test not performed.

In October 2012 (visit 2), the patient visited the centre again and, upon examination, multiple hypochromic macules identical to those observed during the previous visit were observed on both forearms and wrists (symmetrical) and the back (Fig. 2). Histopathology findings were non-specific (interface dermatitis with focal apoptosis), suggesting a toxic dermal-type lesion. More sputum smear microscopy and PCR tests were performed, which were positive for AFB and M. leprae DNA, respectively, in all samples taken (Table 1). The patient was diagnosed with multibacillary (borderline) leprosy and was initially prescribed dapsone (100Ymg/day), clofazimine (50Ymg/day) and rifampicin (600Ymg/month) for one year.

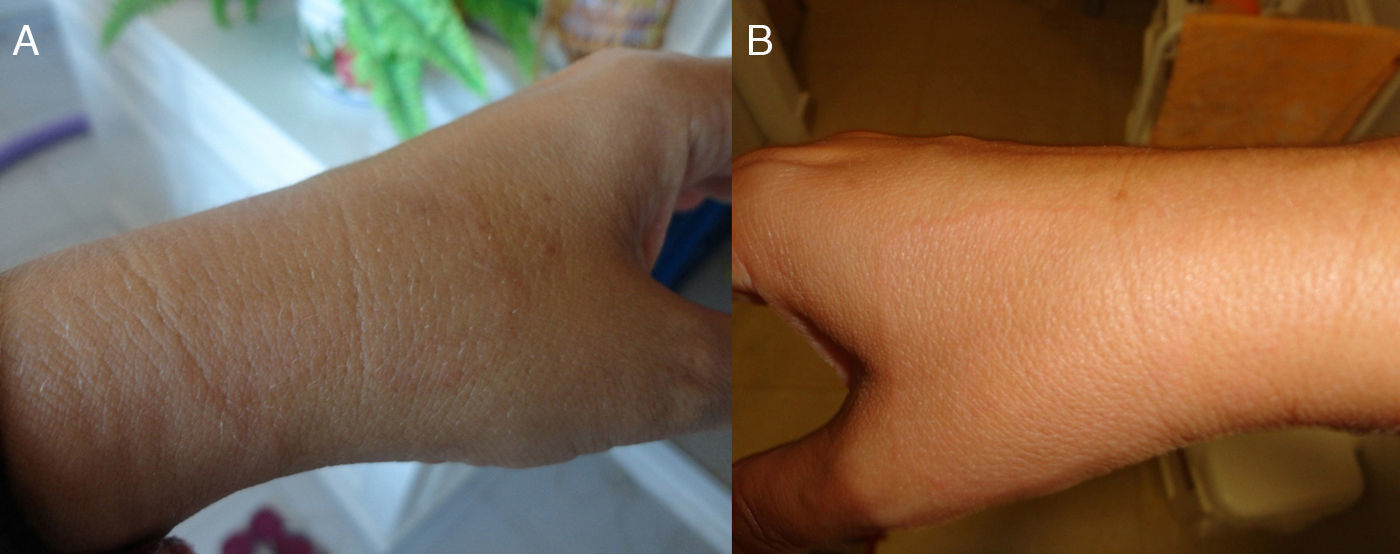

Two months later (visit 3), a good clinical outcome was observed and the erythematous borders were disappearing, although hypochromia remained. Six months after commencing treatment (visit 4), the patient had skin pigmentation from clofazimine therapy and hypochromia on the arms had almost completely disappeared. The sputum smear microscopy and histopathology examination were negative and the PCR test was negative in some samples, with M. leprae DNA detected only in the ear lobe lymph sample. At the 10-month check-up (visit 5), symmetrical hypochromic lesions were observed on the patient's back. Sputum smear microscopy and histopathology examination were performed, which were negative, but M. leprae DNA was detected in the lymph sample taken from the edge of a new lesion on the patient's back. At the following check-up, performed one year after commencing treatment (visit 6), the hypochromic macules on both forearms had disappeared, although lesions remained on the back, and new hypochromic lesions had appeared on both thighs. All tests performed were negative. Electroneurography was performed, which was within normal ranges. Therapy was discontinued. At the check-up performed one year after discontinuing treatment (visit 7), and after clinical assessment (dermatological symptoms had disappeared), the patient was discharged. Sputum smear microscopy, histopathology and PCR were negative. Two years after finishing treatment (visit 8), the patient's sputum smear microscopy and M. leprae DNA (PCR) results were still negative and she had no sequelae of the disease.

Final commentsLeprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by an obligate intracellular mycobacterium called Mycobacterium leprae, which affects the peripheral nervous system, skin and other organs.3 Onset of the disease and the type of symptoms depend on various factors: geographical, socio-economic, age, gender, previous immunisations and, more importantly, the individual's genetic susceptibility, which will condition their immune response to the infection.4 Given that in vitro culture of the bacterium is not possible and there are no reliable serology test methods,5,6 clinical diagnosis is still based on observation of symptoms (cutaneous and/or neurological) and bacteriological testing (sputum smear microscopy and histopathology). However, molecular techniques have recently emerged to support the traditional methods.7 Patient classification is important for determining the most appropriate treatment and guiding patient management when predicting possible complications.8 Observation of any type of nerve involvement, such as hypoesthesia in a cutaneous lesion, is the first clinical sign of suspected leprosy. This finding, together with the presence of acid-fast bacilli in the lesion, confirm diagnosis of the disease.9 No impaired superficial, tactile or motor sensitivity was observed at any time in the patient. Despite the fact that neurological involvement is one of the cardinal signs of leprosy, such symptoms may not be observed in some borderline lepromatous or polar lepromatous patients and in cases of indeterminate leprosy.3,10

Although exposure presumably took place 12–15 years earlier, the patient's disease advanced from the appearance of the first 2 macules (indeterminate leprosy) to generalised lesions in just 18 months, exhibiting numerous, symmetrical lesions in October 2012. The patient's disease quickly evolved to polar lepromatous leprosy and thanks to thorough follow-up, lesions in other organs and systems and the onset of disabilities that are typical in this type of leprosy were avoided. In these cases in which no pathognomonic signs of leprosy are observed, and given the low sensitivity of traditional techniques,11,12 the excellent sensitivity and specificity of molecular techniques may be the key to the aetiological diagnosis of M. leprae.7 Patients with negative sputum smear microscopy results may spread the infection so molecular techniques are an alternative way of identifying these patients and breaking the chain of infection and preventing the development of disabilities.12,13

Although Spain is not among the countries where leprosy is endemic, new endemic and imported cases are constantly being reported.14 In the case of non-specific cutaneous lesions, it is particularly important not to overlook exposure to the disease that occurred many years earlier in order to begin treatment as soon as possible, even in the absence of completely compatible symptoms.

FundingThe authors declare that they did not receive funding to complete this study.

Please cite this article as: Acosta Soto L, Gómez Echevarría JR, Torres Muñoz P. Máculas hipocrómicas sin alteración de la sensibilidad en cooperante. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2018;36:57–59.