Disseminated gonococcal infection (DGI) remains rare, is often preceded by asymptomatic mucosal infection and can be present in the absence of urogenital infection.1,2 Here we report two cases of gonococcal bloodstream infection in two previously healthy patients. Neisseria gonorrhoeae genomes were analyzed further using Whole Genome Sequencing (WGS) to detect antibiotic resistance genes and epidemiological markers.

Case 1A 31-year-old woman was admitted to the emergency department (ED) with persistent odynophagia and fever. On admission her temperature was 37.7°C. Physical examination revealed millimeter papules in both lower extremities. The oropharynx was normal, without tonsillar exudates or adenopathies. Blood analysis showed white blood cells of 11900/mm3 with 83.5% neutrophils. No signs and symptoms related to the genitourinary system were found. Blood cultures (BC) and a pharyngeal sample were collected, and the patient was discharged with amoxicillin/clavulanate (875/125mg).

Case 2A 51-year-old man presented to the ED with a three-day history of fever, polyarthritis, and non-specific skin lesions on the right foot, left leg and right wrist. The day before the onset of symptoms he had received the first dose of hepatitis B vaccine. An adverse reaction to the vaccine was suspected and the patient was admitted to our hospital. Physical examination revealed temperature 38.1°C and BC were drawn.

Aerobic BC vials flagged positive after 28.2 and 23.4h, respectively, and Gram-negative diplococci were observed on Gram stain. After 18h of incubation in 5% CO2 at 35°C, grayish colonies grew on chocolate agar that were identified as N. gonorrhoeae using MALDI-TOF MS (Bruker Daltonics).

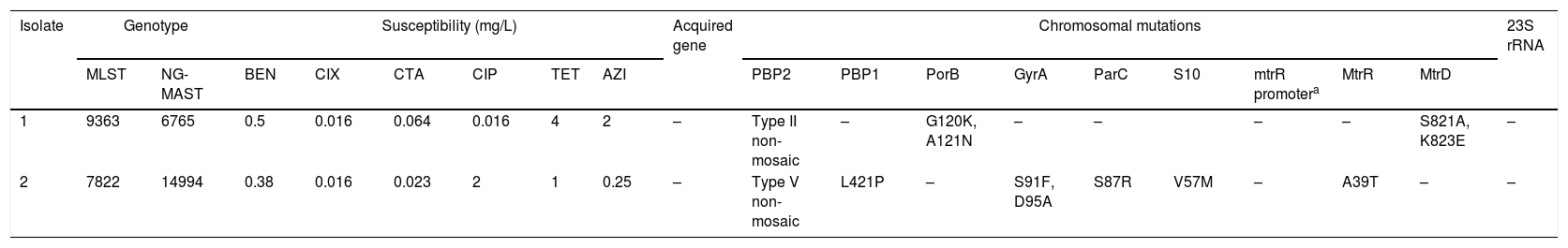

WGS was performed using the MiSeq platform. Assembled genomes of the isolates were input for the ResFinder 3.2 tool in the CGE website (https://cge.cbs.dtu.dk) for identification of acquired antimicrobial resistance genes and chromosomal mutations. The sequence data have been submitted to European Nucleotide Archive (PRJEB37804). Table 1 shows the genotypes, minimum inhibitory concentrations, and antimicrobial resistance determinants of the two isolates.

Genotypes, minimum inhibitory concentrations, and antimicrobial resistance determinants of the two isolates.

| Isolate | Genotype | Susceptibility (mg/L) | Acquired gene | Chromosomal mutations | 23S rRNA | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLST | NG-MAST | BEN | CIX | CTA | CIP | TET | AZI | PBP2 | PBP1 | PorB | GyrA | ParC | S10 | mtrR promotera | MtrR | MtrD | |||

| 1 | 9363 | 6765 | 0.5 | 0.016 | 0.064 | 0.016 | 4 | 2 | – | Type II non-mosaic | – | G120K, A121N | – | – | – | – | S821A, K823E | – | |

| 2 | 7822 | 14994 | 0.38 | 0.016 | 0.023 | 2 | 1 | 0.25 | – | Type V non-mosaic | L421P | – | S91F, D95A | S87R | V57M | – | A39T | – | – |

BEN, Benzylpenicillin; CIX, Cefixime; CTA, Cefotaxime; CIP, Ciprofloxacin; TET, Tetracycline, AZI, Azithromycin.

Given the results, the patient in case 1 was contacted by telephone and was subsequently seen in consultation by a specialist in sexually transmitted infections (STIs). Both patients were started on cefixime 400mg/12h. Serologic tests for HIV, hepatitis A, B and C viruses and Treponema pallidum, as well as culture and PCR (AnyplexTM STI-7, Seegene) on endocervical (patient 1) and urethral (patient 2) specimens were performed yielding negative results.

On direct questioning, patient 1 revealed having had her last sexual intercourse two months ago, having become pregnant and having undergone an elective abortion four weeks after. She also admitted having had oral sex. Patient 2 acknowledged risk sexual behavior including unprotected oral sex with men and women. DNA of N. gonorrhoeae was detected in the pharyngeal smears of both patients. Both patients fully recovered after 4 days of treatment.

DGI is generally characterized by a triad of symptoms known as “arthritis-dermatitis” syndrome (cutaneous lesions, tenosynovitis, and arthralgia) and genitourinary symptoms are usually lacking. However, patients like the one in the first case, may present with nonspecific symptoms like fever, malaise, or myalgia. DGI remains rare and is stated to be more frequent in women since in them primary infection is frequently asymptomatic and, therefore, untreated.3,4 Hematogenous spread is thought to occur 2–3 weeks after primary infection and affects 0.5–3% of infected individuals. Host-dependent factors as well as inherent features of the strain involved might be involved. Menstruation, pregnancy, HIV infection, systemic lupus erythematosus, host complement deficiency, splenectomy or the use of intrauterine devices have been postulated as possible triggers of the infection spread beyond local infectious sites.5–7 A failure of CEACAM3-mediated innate detection might be linked to the ability of gonococci to cause disseminated infections.8 Nevertheless, no single genetic locus has been identified yet as definitive cause of DGI.9

In our study, both patients suffered an alteration of the immune system (pregnancy and vaccination) that could have triggered the spread to the bloodstream. The pharynx has shown to act as an important reservoir for N. gonorrhoeae,9,10 and, although it usually remains asymptomatic, the patient in case 1 presented odynophagia that could not be attributed to any other causative agent.

Clinicians should be aware of the signs and symptoms of DGI, including cutaneous manifestations of this condition and of the fact that absence of genitourinary symptoms does not rule out the diagnosis. Prompt recognition and treatment of pharyngeal asymptomatic carriers will have a positive effect to control the burden of gonorrhea. Regular and periodic STI screening, including extragenital samples, should be implemented as part of the standard of care for patients at risk.