We read with interest the article by Blanco-Sánchez et al., 1 in which they present the case of a school-aged child with fever, parotid inflammation, otorrhoea and retroauricular fistula, in which, the aetiologic diagnosis eventually ends up being actinomycosis. In this regard, we agree with the fact that it is not usual to consider actinomycosis in the differential diagnosis of cervicofacial infections in paediatric cases, and we would like to take the opportunity to present an analysis that we have performed on the behaviour of the disease in Colombia, as well as some comments on its impact in Latin America.

Actinomycosis is a chronic, rare, suppurative and very progressive infection,2 about which there are few studies in Colombia and Latin America. In the case of Colombia there are only 3 publications in journals indexed in Medline (one case report and 2 originals from before 1970),3,4 however, between 2009 and 2013 an average of almost 400 cases per year have been reported in the country.

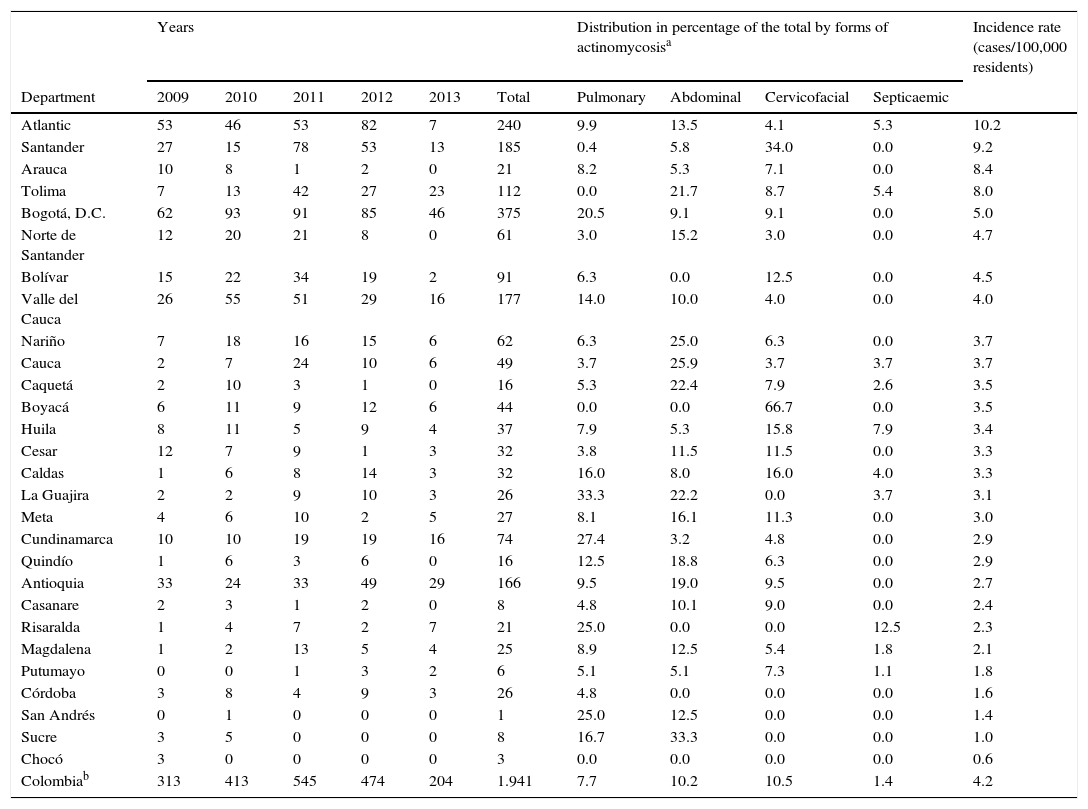

Currently, the Ministry of Health of Colombia, through its SISPRO-Cubo de Datos information system, allows access to the so-called Individual Registry of the Provision of Services, from which it is possible to extract revised and consolidated information on the recorded confirmed diagnoses, according to the International Classification of Disease codes (ICD-10), including cases of actinomycosis (A42.0 to A42.9), in the 2009–2013 period. Using official reference populations by year, department, gender and age group, we estimated the general and specific incidence rates in Colombia.

During the above-mentioned period, there were 1964 cases reported (4.2 cases/100,000 residents; range: 0.6–10.2 in all departments), of which 19.4% corresponded, as in the case of Blanco-Sánchez et al., to children under 10 years of age, for an age-adjusted rate of 44.4 cases/1,000,000 residents (Table 1). When analysing the cases reported in the country, 10.5% corresponded to cervicofacial forms (35.27% of the specified forms, because in 70.26% the form was not reported), and is the most frequent of those reported, followed by abdominal (10.2%) and pulmonary (7.7%) (Table 1), reporting up to more than 30% of the forms in some departments (e.g. Boyacá and Santander) (Table 1). As regards age groups, we found that the highest rate for the cervicofacial form, 9.09 cases/1,000,000 residents, was in children younger than 10 years (Table 1). This coincides with the findings of Blanco-Sánchez et al. However, if we look back, these cases may not be so exceptional in practice, but they are certainly infrequently published. In the literature it has been reported that males have a 3 times greater risk of having the infection than females, for all forms except pelvic. However, in our analysis the opposite was observed, a female:male ratio of 1.4:1 was found, and for abdominal actinomycosis it was 2.0:1. Only the male:female ratio for the septicaemic form was increased, being 1.8:1. In these patients, age was also an important factor, since the rate ratio showed that subjects aged 80 and over had a 2.3 times higher incidence than those aged 10–19.9 years. Likewise, for the pulmonary form, the rate ratio indicates that the incidence was 9.4 times higher in the 70–79.9 year age group compared to the 10–19.9 year age group.

Incidence of actinomycosis and its forms by departments and age groups, Colombia, 2009–2013.

| Years | Distribution in percentage of the total by forms of actinomycosisa | Incidence rate (cases/100,000 residents) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Department | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Total | Pulmonary | Abdominal | Cervicofacial | Septicaemic | |

| Atlantic | 53 | 46 | 53 | 82 | 7 | 240 | 9.9 | 13.5 | 4.1 | 5.3 | 10.2 |

| Santander | 27 | 15 | 78 | 53 | 13 | 185 | 0.4 | 5.8 | 34.0 | 0.0 | 9.2 |

| Arauca | 10 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 21 | 8.2 | 5.3 | 7.1 | 0.0 | 8.4 |

| Tolima | 7 | 13 | 42 | 27 | 23 | 112 | 0.0 | 21.7 | 8.7 | 5.4 | 8.0 |

| Bogotá, D.C. | 62 | 93 | 91 | 85 | 46 | 375 | 20.5 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 0.0 | 5.0 |

| Norte de Santander | 12 | 20 | 21 | 8 | 0 | 61 | 3.0 | 15.2 | 3.0 | 0.0 | 4.7 |

| Bolívar | 15 | 22 | 34 | 19 | 2 | 91 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 4.5 |

| Valle del Cauca | 26 | 55 | 51 | 29 | 16 | 177 | 14.0 | 10.0 | 4.0 | 0.0 | 4.0 |

| Nariño | 7 | 18 | 16 | 15 | 6 | 62 | 6.3 | 25.0 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 3.7 |

| Cauca | 2 | 7 | 24 | 10 | 6 | 49 | 3.7 | 25.9 | 3.7 | 3.7 | 3.7 |

| Caquetá | 2 | 10 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 16 | 5.3 | 22.4 | 7.9 | 2.6 | 3.5 |

| Boyacá | 6 | 11 | 9 | 12 | 6 | 44 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 66.7 | 0.0 | 3.5 |

| Huila | 8 | 11 | 5 | 9 | 4 | 37 | 7.9 | 5.3 | 15.8 | 7.9 | 3.4 |

| Cesar | 12 | 7 | 9 | 1 | 3 | 32 | 3.8 | 11.5 | 11.5 | 0.0 | 3.3 |

| Caldas | 1 | 6 | 8 | 14 | 3 | 32 | 16.0 | 8.0 | 16.0 | 4.0 | 3.3 |

| La Guajira | 2 | 2 | 9 | 10 | 3 | 26 | 33.3 | 22.2 | 0.0 | 3.7 | 3.1 |

| Meta | 4 | 6 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 27 | 8.1 | 16.1 | 11.3 | 0.0 | 3.0 |

| Cundinamarca | 10 | 10 | 19 | 19 | 16 | 74 | 27.4 | 3.2 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| Quindío | 1 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 0 | 16 | 12.5 | 18.8 | 6.3 | 0.0 | 2.9 |

| Antioquia | 33 | 24 | 33 | 49 | 29 | 166 | 9.5 | 19.0 | 9.5 | 0.0 | 2.7 |

| Casanare | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 8 | 4.8 | 10.1 | 9.0 | 0.0 | 2.4 |

| Risaralda | 1 | 4 | 7 | 2 | 7 | 21 | 25.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 12.5 | 2.3 |

| Magdalena | 1 | 2 | 13 | 5 | 4 | 25 | 8.9 | 12.5 | 5.4 | 1.8 | 2.1 |

| Putumayo | 0 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 6 | 5.1 | 5.1 | 7.3 | 1.1 | 1.8 |

| Córdoba | 3 | 8 | 4 | 9 | 3 | 26 | 4.8 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.6 |

| San Andrés | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 25.0 | 12.5 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.4 |

| Sucre | 3 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 8 | 16.7 | 33.3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 1.0 |

| Chocó | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.6 |

| Colombiab | 313 | 413 | 545 | 474 | 204 | 1.941 | 7.7 | 10.2 | 10.5 | 1.4 | 4.2 |

| Age groups (years) | Years | Incidence rate of forms of actinomycosis | Incidence rate (cases/1,000,000 residents) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | 2013 | Total | By age groups (cases/1,000,000 residents) | |||||

| 0–9 | 71 | 82 | 93 | 96 | 39 | 381 | 2.21 | 4.66 | 9.09 | 0.70 | 44.4 |

| 10–19 | 41 | 58 | 89 | 71 | 32 | 291 | 1.25 | 3.76 | 2.62 | 0.11 | 33.1 |

| 20–29 | 49 | 60 | 56 | 72 | 32 | 269 | 2.05 | 3.47 | 1.93 | 0.26 | 34.5 |

| 30–39 | 44 | 60 | 78 | 66 | 22 | 270 | 2.38 | 4.92 | 4.61 | 0.48 | 42.9 |

| 40–49 | 43 | 59 | 90 | 52 | 26 | 270 | 3.34 | 5.09 | 3.69 | 0.18 | 47.4 |

| 50–59 | 27 | 54 | 59 | 58 | 18 | 216 | 5.39 | 3.75 | 3.51 | 1.64 | 50.6 |

| 60–69 | 25 | 30 | 44 | 34 | 19 | 152 | 10.12 | 5.84 | 6.22 | 1.56 | 59.1 |

| 70–79 | 10 | 19 | 34 | 22 | 11 | 96 | 11.72 | 6.89 | 4.14 | 0.69 | 66.2 |

| 80 or more | 4 | 10 | 18 | 8 | 7 | 47 | 9.80 | 14.69 | 6.53 | 4.90 | 76.7 |

In Latin America, there is a limited number of studies published in databases such as Medline (<10),5–10 with a Cuban on urogenital actinomycosis8 being the most representative. In 2004, it evaluated a total of 29,182 biopsies, of which 0.1% (31 cases) corresponded to actinomycosis, 23 cases to in utero infection and 8 in adnexa. One of the related aspects may be the fact that there is a low clinical suspicion, and that microbiological diagnosis is difficult, and in many cases there is even ignorance of the clinical samples that are adequate to make the diagnosis.

To date, we have not found a study similar to our own, based on the discussion of the case of Blanco-Sánchez et al., in which we estimate the incidence of actinomycosis in Colombia. As they say, we agree that it is very important to consider actinomycosis in recurrent chronic cervicofacial suppurative processes, especially in children, and furthermore we believe that it is important to encourage research into infections caused by this and other anaerobic bacteria.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Cardona-Ospina JA, Franco-Herrera D, Failoc-Rojas VE, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. Estimaciones de la incidencia de la actinomicosis en Colombia. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2017;35:393–394.