A 34-year-old Mexican woman with type 1 diabetes mellitus presented with one week history of progressive pain and swelling on the anterior aspect of her neck.

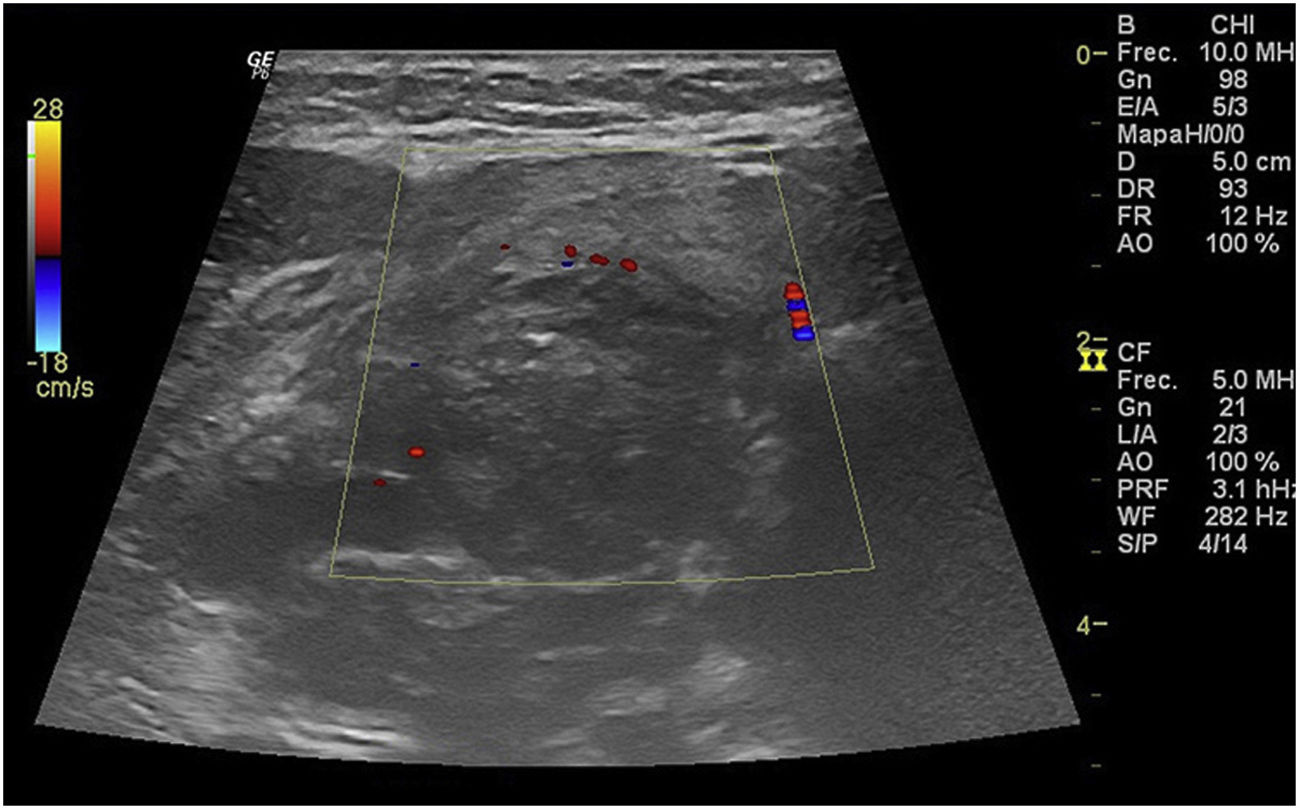

She was afebrile and physical examination revealed a firm, painful midline mass extending laterally into the right neck; there were palpable lymph nodes along the right jugular area. Oropharyngeal examination was normal. Blood biochemical investigations revealed a total leucocyte count of 20,400/mm3 (with 85% neutrophils), increased sedimentation rate (68mm/h) and normal serum levels of thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), triiodothyronine and thyroxine. The patient was HIV negative. Other laboratory examination disclosed a pH at 7.06, positive urine ketones, high serum glucose (438mg/dl) and low serum bicarbonate. Neck ultrasonography (USG) revealed a 5.4cm×3.1cm×3.2cm right thyroid mass with a mixed solid and cystic component (Fig. 1).

She was admitted with a diagnosis of diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) and suspected thyroid infection.

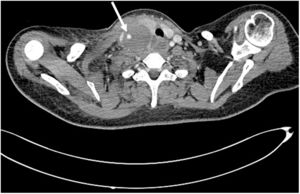

EvolutionTreatment with intravenous normal saline, potassium chloride, insulin infusion and empiric antibiotics (cephalothin) was administered until resolution of the DKA episode. After about 24h of treatment, growth of the neck mass caused severe pain and dysphagia to solids that progressed to liquids; a rise in the serum free thyroxine (2.6ng/dl) was also observed (reference range: 0.8–1.8ng/dl). A computerized tomography (CT) scan of the neck with contrast showed a heterogeneous cystic lesion in the right thyroid lobe extending beyond the expected anterior contour of the gland, with associated tracheal deviation to the left (Fig. 2). By that time, treatment with iv piperacillin/tazobactam had been commenced. At an ultrasound guided puncture of the thyroid, brownish pus was obtained and the abscess was surgically drained in the operating theatre; pus and blood cultures yielded colonies of methicillin-sensitive Staphylococcus aureus. The patient's condition gradually improved with a 10-day course of piperacillin/tazobactam.

Thyroid function tests and sedimentation rate levels were normal at the first month after treatment; there was no evidence of vegetations on echocardiography.

CommentsThe thyroid gland is usually resistant to infection due to its rich blood supply, encapsulation, high iodine and hydrogen peroxide content and good lymphatic drainage. Acute suppurative thyroiditis (AST), including thyroid abscess, constitutes less than 1% of all thyroid diseases, and only 8% of these episodes occur in the adult thyroid.1

Thyroid infection is possible in conditions associated with compromised immune system (including diabetes mellitus), direct extension of adjacent regions (retropharyngeal abscess), direct inoculation of the thyroid (fine needle aspiration) and anatomical abnormalities (pyriform sinus fistula).2 The latter condition originates from a third or fourth branchial cleft cyst anomaly, and can have tracts that connect the pyriform sinus and thyroid gland.3

Pyriform sinus fistula associated infections in adults are rare (92% of the cases occurs in children), and usually occurs in the left upper lobe of the thyroid.3,4 No diagnostic procedures such as a barium investigation or direct laryngoscopy was performed in our patient to exclude anatomic aberrations, thus, the presence of pyriform sinus fistula, though unlikely, cannot entirely be excluded.

In up to 33% of DKA cases, known diabetics experienced episodes of extreme physiologic stress secondary to an infectious process.5 Urinary tract and respiratory tract infections are the main sites of microbiologically documented infection in DKA patients; the principal recovered pathogens in intensive care-unit series are Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumoniae.6 Although the mortality rate associated with DKA is low, treatment of documented bacterial infections is an essential component of the management, given the increased severity of infections in diabetic patients.

Hyperglycemic patients are vulnerable to deep neck infections. Defects in the immune system along with vascular insufficiency render diabetic patients at higher risk for a variety of severe or invasive infections in this space.7 However, the association between AST and DKA has never been mentioned in the published literature.

Patients with AST and abscess typically remain euthyroid, but in some cases, thyrotoxicosis can be seen transiently and explained by the release of pre-synthesized and stored thyroid hormone into the circulation as a result of inflammation and disruption of the thyroid follicles. If this happens, thyroid hormone levels return to normal in most patients within 1–3 months.8

FundingNone declared.

Authors’ contributionsCarlos A. Andrade-Castellanos: conceived and wrote the manuscript.

Olga A. García-Barillas: participated in the design and coordination.

Yancy Y. Erazo-Dorado: collected the data.