During the last decade, infections caused by carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE) have been dramatically increased worldwide. Numerous publications have focused on the epidemiology and risk factors for CPE-related infections,1–3 although studies about surgical patients are scarce. Recognizing patterns in patients admitted to a General Surgery Department (GSD), could be essential to ensure a more rational antibiotic use in this specific setting. We performed a retrospective review including nosocomial CPE infections inpatients admitted to the GSD from January 2013 to December 2016. We analyzed patients with at least one (new) positive culture 48h after admission for a CPE at any location and associated clinical signs or symptoms of infection. The probable infectious source was defined according to microbiological results and the analysis of clinical findings by two physicians in accordance with Centers for Disease Control definitions.4 Patient's samples were collected and incubated based on standard recommendations.5 We investigated the clinical and microbiological characteristics, treatment, complications, antimicrobial susceptibility and risk factors for mortality.

We included 40 patients with a CPE clinical infection: 50% were male, with a mean age of 69.4±13.4 years. Charlson's comorbidity index median value was 3 (range 1–5). The rate of CPE infections in the GSD increased annually from 1.2% in 2013, to 4.7% in 2016.

Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains were the most commonly identified (92.5%), all with the OXA-48-like carbapenemase. Prior to the CPE infection, other non-resistant microorganisms isolated were Gram-negative bacteria (52.5%), Gram-positive bacteria (65%), and fungi (40%). Intra-abdominal site was the most frequent source of infection (55%), followed by surgical wound (22.5%). CPE were susceptible to amikacin (100%), tigecycline (97%), and colistin (76%), and showed increased MICs but acceptable susceptibility to meropenem (64.3%) and imipenem (52.5%). CPE isolates showed low susceptibility rates to ertapenem (8.8%) and ciprofloxacin (5.3%).

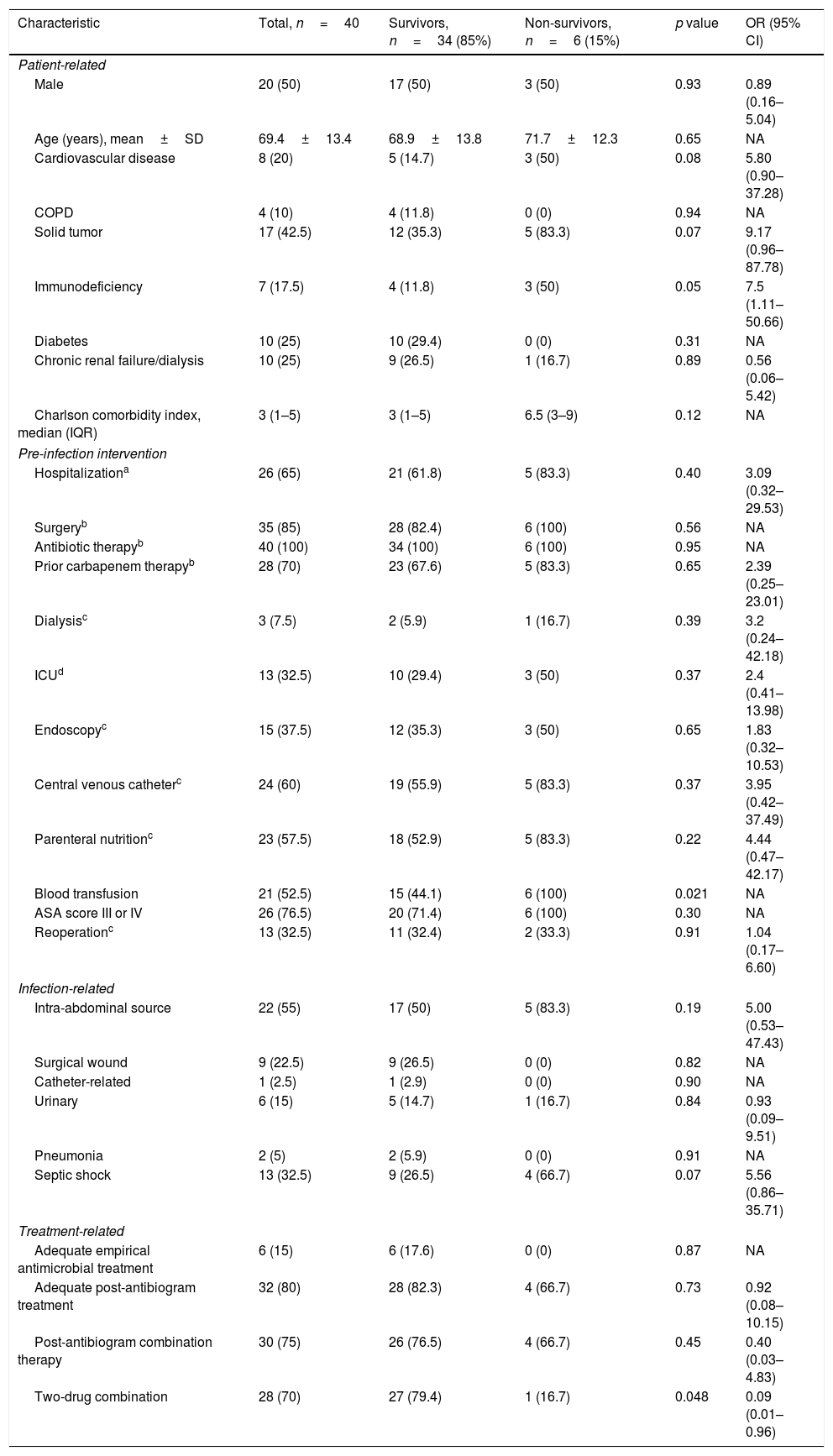

Median hospital stay was 41.5 days (range 26.2–74.5). A surgical procedure had been performed in 35 patients in the previous 30 days, including emergency surgery in 15 cases. A major complication occurred in 23 patients, with a mortality rate of 17.1% in patients who underwent a surgery. A postoperative intra-abdominal infection (IAI) was present in 19 cases. The reoperation rate was 32.5%, without differences regarding mortality compared to non-reoperation. All patients received antibiotic therapy, of which 28 patients received carbapenem therapy. Table 1 shows the analysis of factors associated with mortality. Six patients received an appropriate empirical antibiotic regime, according to the in vitro activity. Appropriate definitive antimicrobial treatment was administered to 32 patients. The mortality rate at 30 days was 15%. Factors associated with mortality were: blood transfusions (p=0.021), and lower rate of major complications (Clavien-Dindo≥III) (p=0.031). A combined definitive two-drug targeted scheme was protector for mortality (p=0.048).

Analysis of factors associated with mortality in patients with infection caused by carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae (CPE).

| Characteristic | Total, n=40 | Survivors, n=34 (85%) | Non-survivors, n=6 (15%) | p value | OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient-related | |||||

| Male | 20 (50) | 17 (50) | 3 (50) | 0.93 | 0.89 (0.16–5.04) |

| Age (years), mean±SD | 69.4±13.4 | 68.9±13.8 | 71.7±12.3 | 0.65 | NA |

| Cardiovascular disease | 8 (20) | 5 (14.7) | 3 (50) | 0.08 | 5.80 (0.90–37.28) |

| COPD | 4 (10) | 4 (11.8) | 0 (0) | 0.94 | NA |

| Solid tumor | 17 (42.5) | 12 (35.3) | 5 (83.3) | 0.07 | 9.17 (0.96–87.78) |

| Immunodeficiency | 7 (17.5) | 4 (11.8) | 3 (50) | 0.05 | 7.5 (1.11–50.66) |

| Diabetes | 10 (25) | 10 (29.4) | 0 (0) | 0.31 | NA |

| Chronic renal failure/dialysis | 10 (25) | 9 (26.5) | 1 (16.7) | 0.89 | 0.56 (0.06–5.42) |

| Charlson comorbidity index, median (IQR) | 3 (1–5) | 3 (1–5) | 6.5 (3–9) | 0.12 | NA |

| Pre-infection intervention | |||||

| Hospitalizationa | 26 (65) | 21 (61.8) | 5 (83.3) | 0.40 | 3.09 (0.32–29.53) |

| Surgeryb | 35 (85) | 28 (82.4) | 6 (100) | 0.56 | NA |

| Antibiotic therapyb | 40 (100) | 34 (100) | 6 (100) | 0.95 | NA |

| Prior carbapenem therapyb | 28 (70) | 23 (67.6) | 5 (83.3) | 0.65 | 2.39 (0.25–23.01) |

| Dialysisc | 3 (7.5) | 2 (5.9) | 1 (16.7) | 0.39 | 3.2 (0.24–42.18) |

| ICUd | 13 (32.5) | 10 (29.4) | 3 (50) | 0.37 | 2.4 (0.41–13.98) |

| Endoscopyc | 15 (37.5) | 12 (35.3) | 3 (50) | 0.65 | 1.83 (0.32–10.53) |

| Central venous catheterc | 24 (60) | 19 (55.9) | 5 (83.3) | 0.37 | 3.95 (0.42–37.49) |

| Parenteral nutritionc | 23 (57.5) | 18 (52.9) | 5 (83.3) | 0.22 | 4.44 (0.47–42.17) |

| Blood transfusion | 21 (52.5) | 15 (44.1) | 6 (100) | 0.021 | NA |

| ASA score III or IV | 26 (76.5) | 20 (71.4) | 6 (100) | 0.30 | NA |

| Reoperationc | 13 (32.5) | 11 (32.4) | 2 (33.3) | 0.91 | 1.04 (0.17–6.60) |

| Infection-related | |||||

| Intra-abdominal source | 22 (55) | 17 (50) | 5 (83.3) | 0.19 | 5.00 (0.53–47.43) |

| Surgical wound | 9 (22.5) | 9 (26.5) | 0 (0) | 0.82 | NA |

| Catheter-related | 1 (2.5) | 1 (2.9) | 0 (0) | 0.90 | NA |

| Urinary | 6 (15) | 5 (14.7) | 1 (16.7) | 0.84 | 0.93 (0.09–9.51) |

| Pneumonia | 2 (5) | 2 (5.9) | 0 (0) | 0.91 | NA |

| Septic shock | 13 (32.5) | 9 (26.5) | 4 (66.7) | 0.07 | 5.56 (0.86–35.71) |

| Treatment-related | |||||

| Adequate empirical antimicrobial treatment | 6 (15) | 6 (17.6) | 0 (0) | 0.87 | NA |

| Adequate post-antibiogram treatment | 32 (80) | 28 (82.3) | 4 (66.7) | 0.73 | 0.92 (0.08–10.15) |

| Post-antibiogram combination therapy | 30 (75) | 26 (76.5) | 4 (66.7) | 0.45 | 0.40 (0.03–4.83) |

| Two-drug combination | 28 (70) | 27 (79.4) | 1 (16.7) | 0.048 | 0.09 (0.01–0.96) |

Data are expressed as n (%), unless otherwise stated.

This study summarizes the outcomes of patients with CPE infections in a GSD. The specific characteristics of this population were age >65 years, previous comorbidities (solid tumor, diabetes, and renal insufficiency), some risk factors for multi-drug-resistant infections (including prior hospitalization and antibiotic therapy), all previously described.1,2,6 In our series, antibiotic therapy had been previously prescribed in all patients (carbapenem therapy in 70%), with high rates of previous hospitalizations, surgery and endoscopic procedures. These findings agree with those of a recently published study of patients admitted in a surgical ICU from a tertiary-care Spanish hospital.6 In addition, other investigations detailed that factors related with the acquisition of a CPE infection in solid organ recipients are poor functional status and frequent antimicrobial therapy, which more frequently occurs in the early post-transplant period.7

Intra-abdominal location was the most common source of CPE infection in our patients (the majority of patients had undergone an abdominal surgery). A two-drug scheme was a protective factor for mortality, and this combination is recommended by current guidelines on the treatment of IAI.8,9 Despite this, several studies have not identified these differences in all patients and propose appropriate monotherapy for patients with low-mortality risk scores.10

Although this study only represents a review of an experience in a GSD of a single-institution with a limited number of patients, it shows a current vision of an increasing problem in a less analyzed population. As physicians prescribing antimicrobials, we may need to pay attention to patients with a specific clinical profile, using a targeted treatment for each patient. Future studies on CPE-related intra-abdominal infections could determine more definite features and outcomes in specific settings with surgical patients.

FundingThe authors report no funding for the present study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors report none conflict of interest to declare for the present study.

Part of this work was presented as an oral free paper in the Spanish National Surgical Meeting that took place in Malaga (Spain) from the 18th to 20th of October, 2017.