Dolosigranulum pigrum (D. pigrum) is a facultative, anaerobic, Gram-positive bacteria first described by Aguirre et al. in 19931 and which is found in the normal microbiota of the oral cavity and upper respiratory tract. There are very few reported cases of D. pigrum infection and most are of pneumonia and septicaemia secondary to respiratory infection2,3. However, cases of synovitis4 and cholecystitis associated with necrotising pancreatitis5 secondary to D. pigrum have also been reported.

In 2013, Sampo et al.6 published a three-case series of infectious D. pigrum keratitis of the eye in elderly patients. In addition, in 2014 Venkateswaran et al.7 described the case of a two-year-old boy with bilateral phlyctenular conjunctivitis associated with D. pigrum, with no signs of active corneal infection.

Although D. pigrum can be a pathogen in various organs of the human body, the factors that determine a high risk of infection have not yet been clearly defined.

We present the case of a 49-year-old man who was referred to the Ophthalmology Department in 2019 due to a progressive loss of vision and bilateral eye pain for several days. This was a homeless patient who lived on the streets and who had a history of parenteral drug abuse and hepatitis C virus (HCV) and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection with no adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). A serological study was ordered and a CD4+ lymphocyte count of 239/microlitre and an HIV viral load of 139,000 copies/mL were detected. The patient had no ophthalmological history of interest, and all the other complementary tests requested (chest X-ray, blood test and urinalysis) revealed no significant findings.

During the patient’s first eye examination, his visual acuity in both eyes was sufficient to see hand movements. Examination of the anterior pole in the right eye by slit lamp revealed a corneal abscess measuring approximately 3 × 3 mm, with a 2-mm hypopyon. In the left eye, a central corneal abscess measuring approximately 4 × 4 mm was also identified, associated with a 1-mm hypopyon, as well as signs of corneal neovascularisation. The rest of the eye examination was normal.

In light of these clinical findings, it was decided to begin empirical antibiotic therapy with fortified ceftazidime and vancomycin eye drops every hour and daily atropine eye drops in both eyes. Voriconazole eye drops were also included every two hours due to suspected fungal keratitis.

A corneal scraping specimen was previously taken with different scalpel blades to collect a biological sample from each abscess, and a microbiological study was requested, which identified D. pigrum in the bacteriological culture in both eyes. The cultures for fungi and anaerobic bacteria were sterile. The antibiogram performed found D. pigrum to be susceptible to all the antibiotics tested.

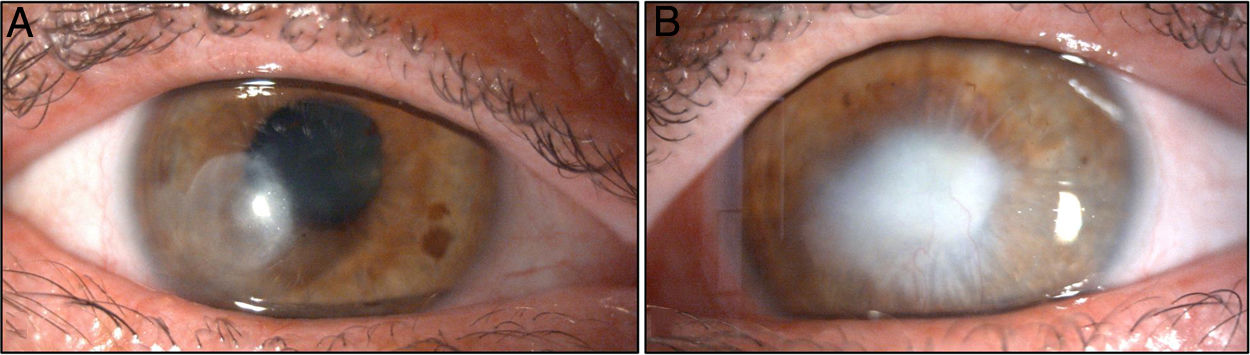

One week after the diagnosis, it was decided to suspend the antifungal treatment, and antibiotic therapy was switched to moxifloxacin every four hours due to the patient’s poor tolerance of the fortified vancomycin eye drops. The patient’s clinical course in both eyes was favourable, with good response to the antibiotics prescribed. About one month after starting antibiotic therapy and with no signs of infectious activity, it was decided to initiate treatment with a tapering regimen of dexamethasone eye drops in order to minimise stromal fibrosis. The patient currently has a corneal leukoma in the temporal paracentral area of his right eye (Fig. 1A) associated with significant stromal thinning that generates irregular corneal astigmatism. He also has a corticonuclear cataract and approximately 270° of posterior pupillary synechiae.

In the left eye, the patient has a large central leukoma with signs of neovascularisation (Fig. 1B) and corneal remodelling, as well as anterior pupillary synechia of probable inflammatory aetiology.

Finally, the fundus of the right eye was found to be normal, while in the left, an eye ultrasound was performed due to media opacity, which was also normal. Intraocular pressure was 16 and 18 mmHg, respectively. The patient's best-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 20/200 in his right eye and hand movements in his left eye.

The patient is currently receiving combination ART with elvitegravir, cobicistat, emtricitabine and tenofovir, with good treatment adherence. We shall consider a surgical approach involving penetrating keratoplasty associated with cataract surgery in both eyes one year after diagnosis if the patient's clinical course is adequate and his adherence to the ophthalmological and antiretroviral therapy is good.

The normal microbiota of the respiratory tract is made up of more than 140 different families of microorganism, most of which do not have pathogenic potential. However, some species can cause infections that predominantly affect the nasopharynx, upper respiratory tract and lungs. The most well-known are Moraxella catarrhalis, Haemophilus influenzae and Streptococcus pneumoniae. These microorganisms are also known to be pathogens of the eye, responsible for most cases of infectious keratitis. D. pigrum is a Gram-positive bacterium that is part of the lung microbiota. Venkateswaran et al.7 reported the case of a two-year-old boy with a history of allergic extrinsic asthma who presented with phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis associated with D. pigrum isolated in a conjunctival swab. In the article, the authors hypothesise that the immune dysregulation from the patient’s underlying asthma may have contributed to his phlyctenular keratoconjunctivitis, which could be triggered by D. pigrum.

In their article on a three-case series of elderly patients with unilateral D. pigrum keratitis, Sampo et al.6 report a history of rheumatoid arthritis and immunosuppressive therapy for one of the patients. Two of the cases had corneal perforation secondary to infection, and the authors discuss the possible increased risk of perforation in D. pigrum keratitis. In our case, we found no evidence of corneal perforation secondary to infection. The finding of anterior synechiae of the iris to the cornea can be a secondary sign of prior corneal perforation that spontaneously resolved due to the tamponade caused by iris incarceration in the corneal stroma. However, it is usually associated with significant stromal thinning.

The clinical signs and symptoms reported herein describe bilateral infectious keratitis in an HIV-positive patient from whom D. pigrum was isolated from the microbiological cultures performed. We have not found any other published case of bilateral infectious D. pigrum keratitis or D. pigrum extraocular infection in an HIV-positive patient. D. pigrum eye infection is extremely rare. In our case, the patient’s immunosuppression caused by HIV infection was probably a risk factor that contributed to the clinical signs and symptoms.

In our experience, infectious D. pigrum keratitis responds well to treatment because it is susceptible to most antibiotics used in routine clinical practice. Having said that, intrinsic resistance of this bacteria to erythromycin has been reported8.

This is the first published case of bilateral infectious D. pigrum keratitis and it can serve as a reference for other researchers and clinicians treating patients with infections by this microorganism. Moreover, we consider it striking that all the patients reported by Sampo et al.6 were patients with a history of immunosuppression, either due to their advanced age or autoimmune disease. Our case concerned a patient with untreated HIV infection. This factor, together with the patient's poor hygiene and state of poverty, could have contributed to bilateral corneal D. pigrum infection.

FundingNo funding was received for this study.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Please cite this article as: Monera-Lucas CE, Tarazona-Jaimes CP, Escolano-Serrano J, Martínez-Toldos JJ. Queratitis infecciosa bilateral por Dolosigranulum pigrum en un paciente con infección por VIH. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2021;39:521–522.