Cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection is the most common congenital infection in the industrialised countries. A worldwide prevalence of 0.67% is estimated,1 although these values vary depending on the country, which is 0.48% in Spain.2

Congenital CMV produces high morbidity and mortality; 20% of symptomatic newborns develop sensorineural hearing loss and psychomotor retardation and 4% die. In addition, 13% of asymptomatic newborns develop long-term sequelae.3

Despite the fact that serological screening during pregnancy is not recommended in Spain, in recent years certain diagnostic and therapeutic innovations have reopened this debate.4,5

The worldwide prevalence of CMV in women of childbearing age is around 86% and increases with age.6,7 These figures are higher than those of syphilis, human immunodeficiency virus infection or hepatitis B virus. In Spain there are no current data on the prevalence of CMV in pregnant women, so we proposed this study to ascertain seroprevalence in pregnant women in our health area in Madrid.

A retrospective observational study was carried out between 2018 and 2019 including pregnant women with CMV serology in the first trimester. An IgG avidity study was performed in IgG- and IgM-positive women, whereas those with low avidity (<50%) underwent diagnostic amniocentesis.

Architect (Abbott) CMIA (Chemiluminescent Microparticle Enzyme Immunoassay) reagents were used to perform CMV IgG, CMV IgM and avidity testing. The CMV quantitative PCR was performed in STARlet (Werfen) with the Altona RealStar® CMV PCR Kit 1.0 reagent.

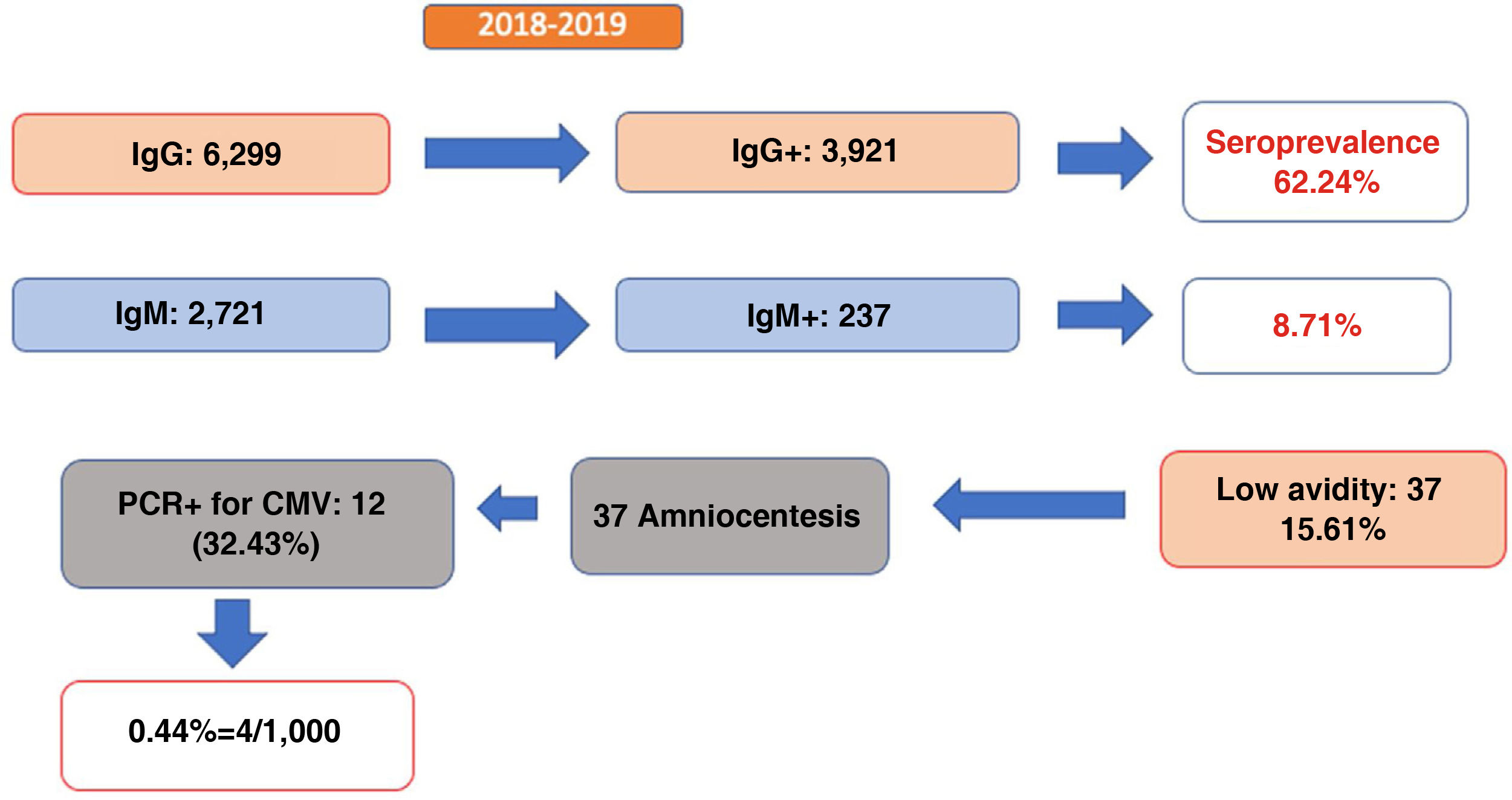

Of the 10,431 pregnant women seen during this period, IgG antibodies were determined in 6,299 (60.39%) of them, 3,921 of which were positive, which represents a seroprevalence of 62.2%. Simultaneous determination of IgM was performed in 2,721 pregnant women, 237 (8.71%) of whom tested positive (Fig. 1).

Of the pregnant women with positive IgM antibodies, 37 (15.6%) had low IgG avidity, suggesting an infection in the previous 3–6 months. This indicates that 1.35% of women screened for IgM and IgG antibodies were at risk of gestational infection in the first trimester. Of the 37 amniocenteses performed, 12 (32.43%) had a positive PCR for CMV in amniotic fluid, indicative of foetal infection and confirmed with PCR in urine at birth.

Therefore, we can conclude that among pregnant women who have undergone serological screening using IgM and IgG, the rate of congenital CMV in our area is 0.44%. If we only take pregnant women with positive IgG and IgM antibodies into account, this percentage rises to 5%, and is 32% in the case of low IgG antibody avidity.

This study analyses the seroprevalence of CMV in pregnant women in our country, with data that could be extrapolated to other populations with similar characteristics.

In our setting, 62% of pregnant women are seropositive, and more than one third are susceptible to suffering from a primary infection during pregnancy.

1.3% of women with positive IgM and IgG had a result indicative of infection in the previous three to six months and 32% of them developed a congenital infection. The global burden of congenital infection in our setting is surely higher, since infections produced after the first trimester and reinfections/reactivations in immune women have not been considered.

New therapeutic options are currently being tested in pregnant women to prevent foetal infection.8 Thus, a randomised, placebo-controlled clinical trial shows a significant decrease in foetal infection rates in pregnant women infected in the first trimester who received treatment with valacyclovir (11% vs. 48%; p = 0.020).5 In addition, different groups have studied the role of hyperimmune gamma-globulin, and although there are questions about its efficacy, one study demonstrates a benefit in the transmission of infection to the foetus using high fortnightly doses (7.5% vs. 35.2% in the historical control group).9

However, it should be noted that knowledge of the serological status only provides useful information for detecting and treating primary CMV infections in pregnant women. For this reason, an effort must be made to improve serological techniques for the diagnosis of reinfections/reactivations, since they can also cause serious disease in the foetus.2

Additionally, serological screening in the first trimester would allow us to remind patients of the primary prevention recommendations, which should be issued to all pregnant women at their first visit, regardless of their serological status, given the possibility of primary infections and reinfections. Finally, it would make it possible to detect congenital infections with a risk of long-term sequelae,10 guaranteeing an adequate follow-up of infected children.