There is a high rate of occult infection and late diagnosis in HIV. Hospital emergency departments (ED) are an important point of health care. The present work aims to know the number of missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis occurring in the ED.

MethodRetrospective multicenter cohort study that included all patients diagnosed with HIV infection in 2019 in 27 Spanish hospitals in 7 different autonomous communities. All ED consultation episodes in the 5 years prior to diagnosis were reviewed to find out the reason for consultation and whether this represented a missed opportunity for HIV diagnosis.

ResultSeven hundred twenty-three patients were included, and 352 (48.7%, 95%CI: 45.1%–52.3%) had at least one ED visit during the 5 years prior to diagnosis (median 2, p25–p75: 1–4). One hundred and eighteen patients (16.3%, 95%CI: 13.8%–19.2%) had a missed diagnostic opportunity. The main consultations were drug use [145 (15%)], sexually transmitted infections [91 (9.4%)] and request for post-exposure HIV prophylaxis [39 (4%)]. One hundred and fifty-five (42.9%) of the 352 had less than 350 CD4/mm3 when the HIV diagnosis was established. In patients with previous ED visits, the mean time to diagnosis from this visit was 580 (SD 647) days.

ConclusionsSixteen percent of patients diagnosed with HIV missed the opportunity to be diagnosed in the 5 years prior to diagnosis, highlighting the need to implement ED screening measures different from current ones to improve these outcomes.

Existe una elevada tasa de infección oculta y diagnóstico tardío en el VIH. Los servicios de urgencias hospitalarios (SUH) son un punto importante de atención sanitaria. El presente trabajo tiene el objetivo conocer el número de oportunidades perdidas para el diagnóstico de VIH que ocurren en los SUH.

MétodoEstudio multicéntrico de cohortes retrospectivo que incluyó a todos los pacientes diagnosticados de infección por VIH en el año 2019 en 27 hospitales españoles de 7 comunidades autónomas diferentes. Se revisaron todos los episodios de consulta en los SUH en los 5 años previos al diagnóstico para conocer el motivo de consulta y si éste representaba una oportunidad perdida para el diagnóstico de VIH.

ResultadoSe incluyeron 723 pacientes, y 352 (48,7%, IC95%:45,1%–52,3%) presentaron al menos una visita a un SUH durante los 5 años anteriores al diagnóstico (mediana 2, p25–p75:1–4). Ciento dieciocho pacientes (16,3%, IC95%: 13,8%–19,2%) presentaron oportunidad perdida de diagnóstico. Las principales consultas fueron consumo de drogas [145 (15%)], infecciones de transmisión sexual [91 (9,4%] y solicitud de profilaxis de VIH post -exposición [39 (4%)]. Ciento cincuenta y cinco (42,9%) de los 352 tenían menos de 350 CD4/mm3 cuando se estableció el diagnóstico de VIH. En los pacientes con visitas previas a urgencias, el tiempo medio hasta el diagnóstico desde esta visita fue de 580 (DE 647) días.

ConclusionesEl 16% de los pacientes diagnosticados de VIH perdieron la oportunidad de ser diagnosticados en los 5 años previos al diagnóstico, lo que pone de manifiesto la necesidad de implementar medidas de cribado en los SUH diferentes a las actuales para mejorar estos resultados.

HIV infection remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide. In 2019, it was the eleventh leading cause of death around the world1. Spain reported 2,698 new diagnoses in 2019, corresponding to an estimated rate of 7.46 per 100,000 population2.

In 2010, the World Health Organization and the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control introduced a programme to expand diagnosis of HIV infection in all healthcare settings in Europe3,4, backed by various studies and proposals from scientific associations5–7. The end goal of this initiative is to diagnose HIV infection earlier in its course, resulting in fewer late diagnoses, improvements in infected individuals’ prognosis and quality of life, and decreased rates of HIV transmission8–10. In 2014, the Spanish Ministry of Health, Consumer Affairs and Social Welfare, in collaboration with multiple medical associations and other organisations (none representing emergency medicine), promoted guidelines with recommendations for early diagnosis of HIV infection, intended to apply this initiative to the Sistema Nacional de Salud [Spanish National Health System] as a whole11.

All these guidelines promote efforts aimed at diagnosing HIV in people who seek healthcare services for other conditions in which HIV prevalence exceeds 0.1%. These conditions are divided into HIV-associated diseases and HIV indicator conditions. When they are diagnosed, it is recommended that HIV serology be performed at the level of care at which patients are seen, as well as in hospital accident and emergency departments (HAEDs). Despite these recommendations, in Spain today, 13% of infected individuals remain unaware of their serological status, and 50% of diagnoses are made late, when the patient has a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3.9 Missed opportunities for diagnosis are key to changing the course of the epidemic and preventing its spread.

In Spain, HAEDs are important points of care, with 23,602,900 visits in 2019 corresponding to an estimated frequency of 501.1 visits per 1,000 population12. A recent study conducted in Aragon found that one in three missed opportunities occurred in accident and emergency departments, and that the prevalence of late diagnosis increased along with the frequency of visits to such departments13. In view of the currently limited data in Spain, this study was proposed to estimate the number of missed opportunities detected on HAEDs by analysing visits in the five years prior to HIV diagnosis, based on an extensive sample representative of departments in various Autonomous Communities of Spain. In addition, characteristics of patients with a missed opportunity for early diagnosis of HIV infection were compared.

MethodologyStudy designWe conducted a multicentre retrospective cohort study that included all patients diagnosed with HIV infection in 2019. This information was collected from hospital microbiology department databases. Hospital data was compared to ensure the absence of replicated cases previously diagnosed with HIV across the different sites. All accident and emergency department visits in the five years prior to diagnosis were retrospectively reviewed. A total of 27 Spanish HAEDs belonging to the Infectious Diseases in Emergency Medicine Working Group of the Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias [Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine] (INFURG-SEMES) Site Network participated in the study.

Variables were recorded in a shared standardised electronic form based on patient medical record data. The patients’ medical records, both those available at the site and those prepared at other levels of care in an Autonomous Community and accessible electronically, were reviewed. Variables were defined in advance by the group of researchers, and then circulated among the participating investigators from each HAED involved by the principal investigator from each site.

The study complied with all local and international protocols and standards (the Declaration of Helsinki) for the use of patient data which were encoded to ensure the confidentiality thereof. The ethics committee at the reference site (Hospital Clínico San Carlos [San Carlos Clinical Hospital]) approved the conduct of the study (20/078-E).

Definition of variablesThe primary endpoint was having made at least one visit to the accident and emergency department in the past five years. A missed opportunity was defined as the patient visiting the HAED for a reason related to HIV infection (see Appendix B Annex 3) and not undergoing a test to detect HIV, either in the HAED itself or at another level of care, due to direct referral from the HAED. For some analyses, a HAED visit was also used as a classifier variable. Demographic variables (age, sex, nationality, whether the patient had healthcare coverage), date of serological diagnosis of HIV, immunological and virological status at diagnosis (CD4 count and viral load), and route of HIV transmission were collected as well. For each accident and emergency department visit, information was collected on the main diagnosis or observation made: sexually transmitted infection, request for post-exposure prophylaxis, unexplained weight loss, mononucleosis-like syndrome, pneumonia, high-risk practices (chemsex, parenteral drug use or high-risk sexual behaviour), herpes zoster virus infection, opportunistic infection or HIV indicator condition (seborrhoeic dermatitis, unexplained lymphadenopathy, leukopenia, prolonged thrombocytopenia, lung cancer, viral hepatitis, cervical or anal dysplasia or cancer, severe psoriasis, or peripheral neuropathy).

Finally, the patient’s final destination after initial emergency care in the accident and emergency department was collected: observation, short-stay unit (SSU), hospital admission (infectious disease unit, internal medicine department, another medical department or surgical department), discharge (referral to an outpatient clinical specialising in dermatology, internal medicine, microbiology, infectious disease, sexually transmitted diseases or primary care).

Time to diagnosis for each patient was defined as the period between the first visit with a diagnosis of an HIV indicator condition, or a main diagnosis associated with HIV infection, and the time of serological diagnosis of HIV in 2019.

For conditions associated with a high prevalence of HIV infection, the definitions used in the Guía de Recomendaciones para el diagnóstico Precoz del VIH en el ámbito sanitario [Guidelines with Recommendations for Early Diagnosis of HIV in Healthcare Settings], published by the Spanish Ministry of Health, Social Services and Equality in 201411, listed in Appendix B Annex 3.

Statistical analysisThe distribution of quantitative variables is presented in terms of mean and standard deviation (SD) or median and interquartile range (IQR), depending on the distribution of the data. The distribution of the qualitative variables is presented in terms of absolute and relative frequencies. To study associations between qualitative variables, the chi-squared (χ2) test or Fisher’s exact test was used, if more than 25% of the expected frequencies were less than five. To compare the distribution of quantitative variables, Student's t test or the non-parametric Mann–Whitney U test was used, depending on the distribution of the data. In addition, multivariate analysis was performed using binary logistic regression models. All tests were considered bilateral, and statistical significance was set at a probability of less than 0.05. Statistical analysis was performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS 18.0®) software program.

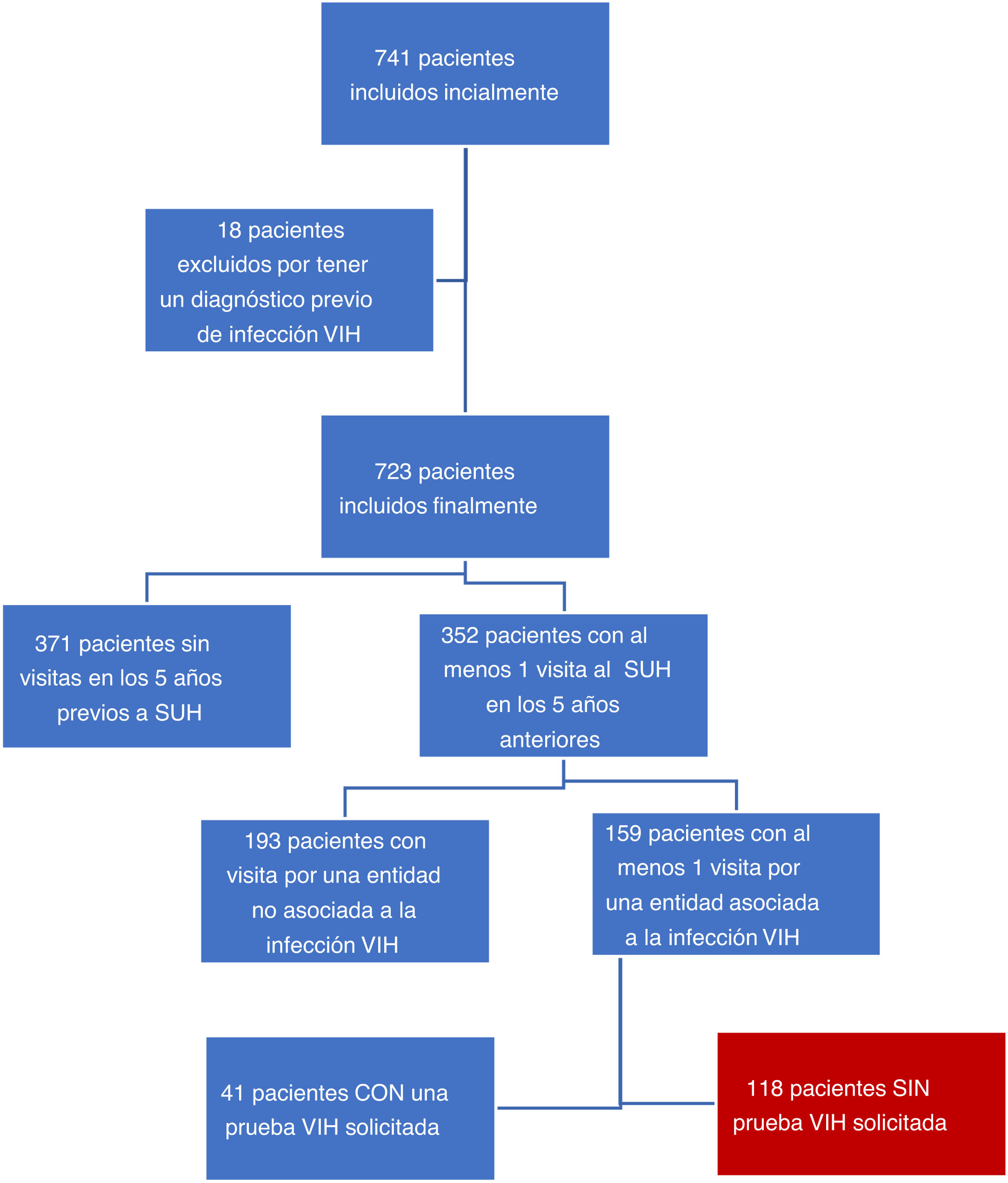

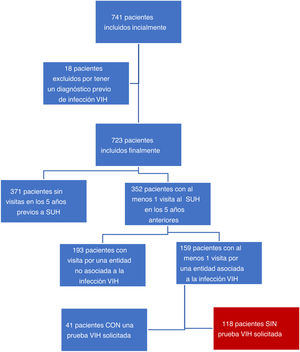

ResultsA total of 27 HAEDs from seven different Autonomous Communities participated in the study. Initially, 741 patients were included in the study. Of these, 18 (2.4%) were ultimately excluded as a diagnosis of HIV prior to the study period was confirmed. Among the patients who were ultimately included, 371 (50.06%) had not made any visits to the accident and emergency department in the five years prior to 2019. A total of 352 (48.7%; 95% CI: 45.1%–52.3%) patients had made at least one visit to the accident and emergency department in the five years prior to diagnosis, for a cumulative total amongst them of 967 visits: 376 due to HIV-associated diseases and 39 due to HIV indicator conditions. One hundred and fifty-nine patients had made visits to the accident and emergency department related to HIV infection. In 41 of these cases, HIV serology was performed and came back negative (25.8%; 95% CI: 19.6%–33.1%). The remaining 118 patients did not undergo any testing for HIV infection during the visit, and were considered patients with a missed opportunity for diagnosis of HIV infection (16.3%; 95% CI: 13.8–19.2%) (Fig. 1).

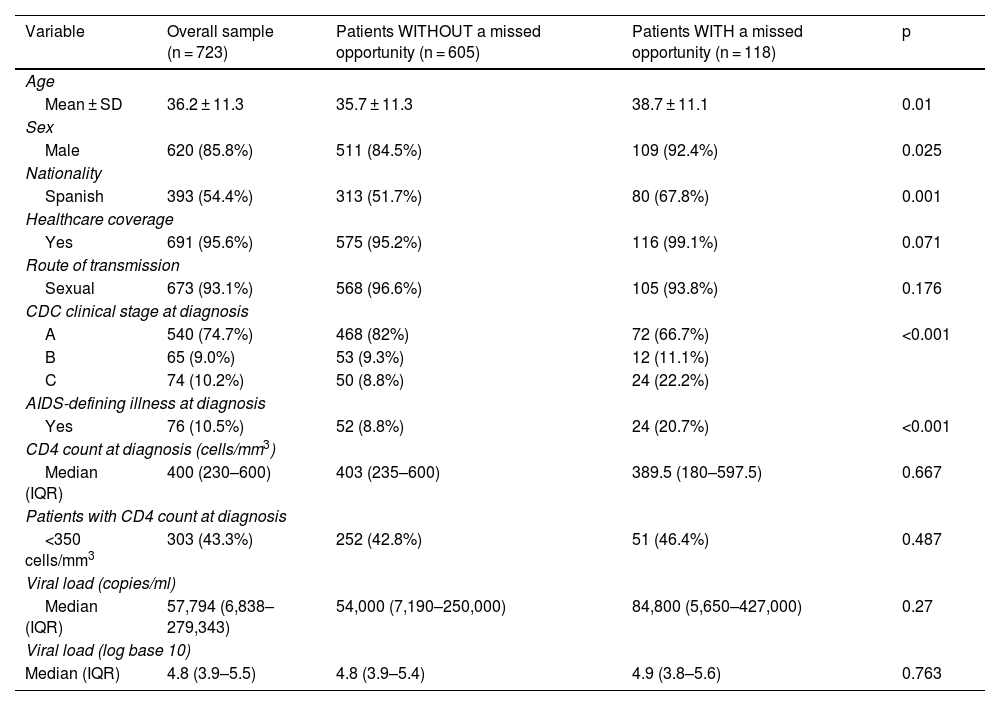

From a demographic point of view, 620 (85.8%) were male, and the mean age at diagnosis was 36 (SD 11.3) years. Three hundred and ninety-three (54.4%) were Spanish, and 686 (94.9%) had public healthcare coverage. The most common route of transmission was sexual, in 673 (93.1%) patients. Table 1 lists the characteristics of the study population. From an immunological and virological perspective, patients had a mean CD4 count of 400 (IQR 230–600) cells/mm3 and a median viral load of 57,794 (IQR 6,838–279,343) copies at the time of HIV diagnosis.

Characteristics of the study population and univariate analysis between the population with and the population without a missed opportunity in the accident and emergency department.

| Variable | Overall sample (n = 723) | Patients WITHOUT a missed opportunity (n = 605) | Patients WITH a missed opportunity (n = 118) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 36.2 ± 11.3 | 35.7 ± 11.3 | 38.7 ± 11.1 | 0.01 |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 620 (85.8%) | 511 (84.5%) | 109 (92.4%) | 0.025 |

| Nationality | ||||

| Spanish | 393 (54.4%) | 313 (51.7%) | 80 (67.8%) | 0.001 |

| Healthcare coverage | ||||

| Yes | 691 (95.6%) | 575 (95.2%) | 116 (99.1%) | 0.071 |

| Route of transmission | ||||

| Sexual | 673 (93.1%) | 568 (96.6%) | 105 (93.8%) | 0.176 |

| CDC clinical stage at diagnosis | ||||

| A | 540 (74.7%) | 468 (82%) | 72 (66.7%) | <0.001 |

| B | 65 (9.0%) | 53 (9.3%) | 12 (11.1%) | |

| C | 74 (10.2%) | 50 (8.8%) | 24 (22.2%) | |

| AIDS-defining illness at diagnosis | ||||

| Yes | 76 (10.5%) | 52 (8.8%) | 24 (20.7%) | <0.001 |

| CD4 count at diagnosis (cells/mm3) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 400 (230–600) | 403 (235–600) | 389.5 (180–597.5) | 0.667 |

| Patients with CD4 count at diagnosis | ||||

| <350 cells/mm3 | 303 (43.3%) | 252 (42.8%) | 51 (46.4%) | 0.487 |

| Viral load (copies/ml) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 57,794 (6,838–279,343) | 54,000 (7,190–250,000) | 84,800 (5,650–427,000) | 0.27 |

| Viral load (log base 10) | ||||

| Median (IQR) | 4.8 (3.9–5.5) | 4.8 (3.9–5.4) | 4.9 (3.8–5.6) | 0.763 |

IQR: interquartile range; ml: millilitre; SD: standard deviation.

Table 1 summarises the distribution of the patients’ characteristics based on whether they had made prior visits to the accident and emergency department that could or could not be considered a missed opportunity. Patients with a missed opportunity were statistically significantly more likely to be older, male, foreign and in CDC stage C at diagnosis, and to have an AIDS-defining illness at diagnosis. Of the patients, 252 (42.8%) without a missed opportunity, and 51 (46.4%) with a missed opportunity had a CD4 count below 350 CD4/mm3 (p = 0.487). The multivariate analysis, which included age, sex, nationality, route of transmission, AIDS-defining illness, CD4 count and viral load at diagnosis, revealed that only sex (p = 0.04) and having an AIDS-defining illness (p < 0.001) were independent factors associated with a missed opportunity.

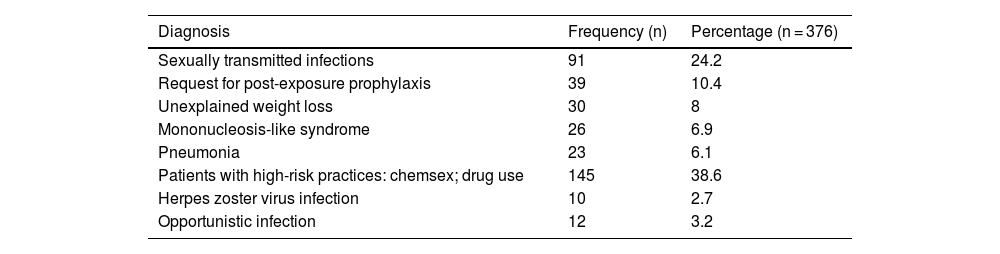

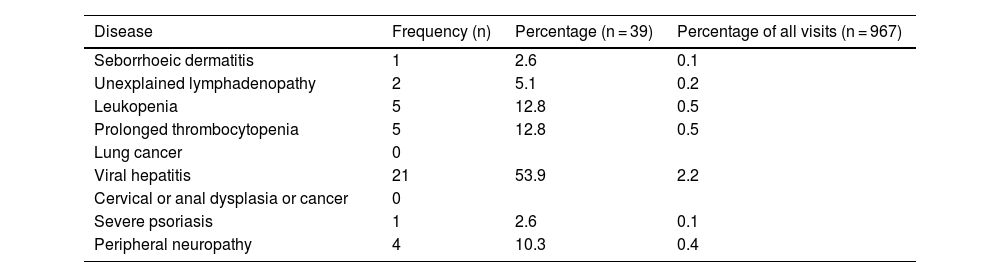

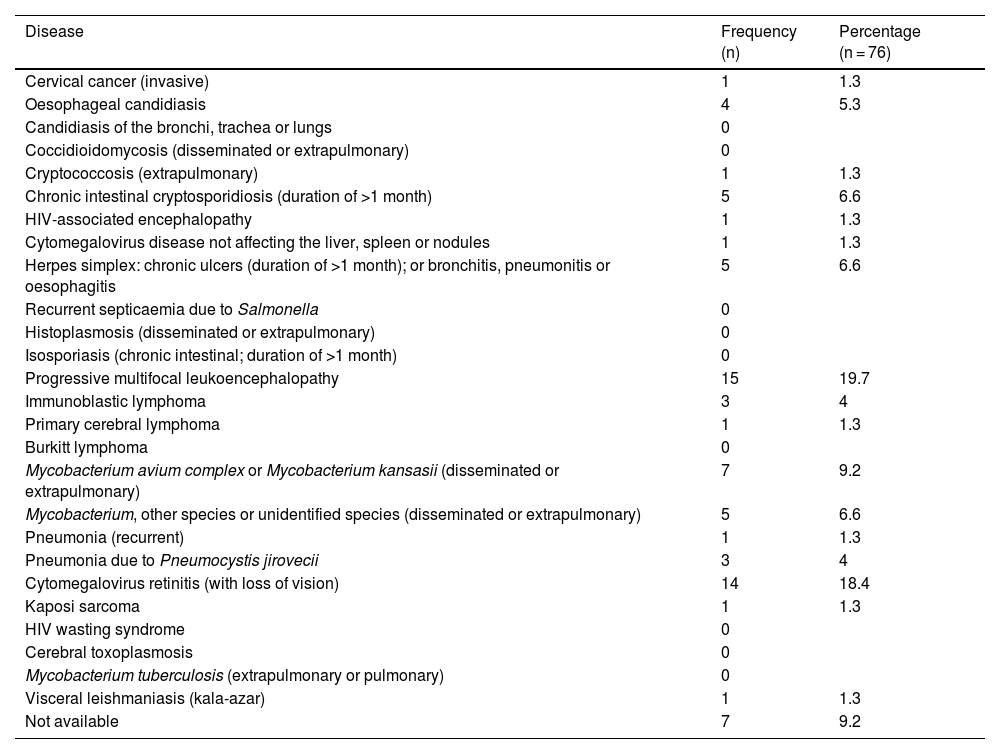

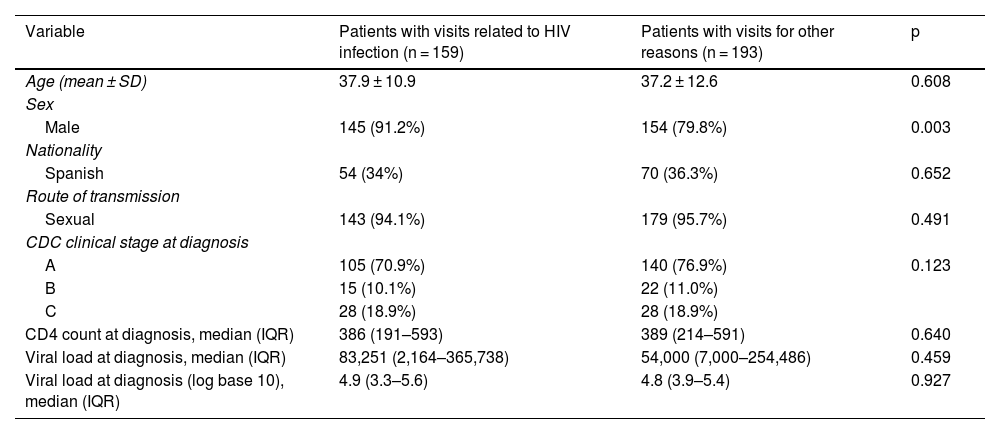

Patients who had previously visited HAEDs did so a mean of 2.9 (SD 2.5) times, with a median of 2 (minimum of 1; maximum of 17). Overall, 967 visits were made. In 271 visits (28%), the main diagnosis made in the accident and emergency department was an HIV-associated disease. This distribution is shown in Table 2. These 271 visits were made by 145 (41.19%) patients. In 39 (4%) visits, an HIV indicator condition was diagnosed. They are described in Table 3. These 39 visits were made by 24 (3.52%) of the patients with accident and emergency department visits. In total, 159 (45.2%) patients were seen in the accident and emergency department in the five years prior to HIV diagnosis for an HIV indicator condition or an HIV-associated disease. Seventy-six (10.5%) of the 723 included presented an AIDS-defining illness at the time of diagnosis of HIV infection; the most common was progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy, followed by cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision) (Table 4). Of them, 52 (8.8%) were classified as without a missed opportunity, and 24 (20.7%) were classified as with a missed opportunity (p < 0.001). In the univariate analysis that compared the characteristics of patients with HIV infection-related visits to those with visits exclusively for other reasons, we only found statistically significant differences with regard to sex (Table 5). These results were maintained in the adjusted multivariate analysis, which included age, sex, nationality, route of transmission, AIDS-defining illness, CD4 count and viral load at diagnosis.

Situations or diseases detected in accident and emergency departments associated with HIV infection.

| Diagnosis | Frequency (n) | Percentage (n = 376) |

|---|---|---|

| Sexually transmitted infections | 91 | 24.2 |

| Request for post-exposure prophylaxis | 39 | 10.4 |

| Unexplained weight loss | 30 | 8 |

| Mononucleosis-like syndrome | 26 | 6.9 |

| Pneumonia | 23 | 6.1 |

| Patients with high-risk practices: chemsex; drug use | 145 | 38.6 |

| Herpes zoster virus infection | 10 | 2.7 |

| Opportunistic infection | 12 | 3.2 |

Prior visits with a main diagnosis of an HIV indicator condition.

| Disease | Frequency (n) | Percentage (n = 39) | Percentage of all visits (n = 967) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Seborrhoeic dermatitis | 1 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| Unexplained lymphadenopathy | 2 | 5.1 | 0.2 |

| Leukopenia | 5 | 12.8 | 0.5 |

| Prolonged thrombocytopenia | 5 | 12.8 | 0.5 |

| Lung cancer | 0 | ||

| Viral hepatitis | 21 | 53.9 | 2.2 |

| Cervical or anal dysplasia or cancer | 0 | ||

| Severe psoriasis | 1 | 2.6 | 0.1 |

| Peripheral neuropathy | 4 | 10.3 | 0.4 |

AIDS-defining illnesses at the time of diagnosis of HIV infection.

| Disease | Frequency (n) | Percentage (n = 76) |

|---|---|---|

| Cervical cancer (invasive) | 1 | 1.3 |

| Oesophageal candidiasis | 4 | 5.3 |

| Candidiasis of the bronchi, trachea or lungs | 0 | |

| Coccidioidomycosis (disseminated or extrapulmonary) | 0 | |

| Cryptococcosis (extrapulmonary) | 1 | 1.3 |

| Chronic intestinal cryptosporidiosis (duration of >1 month) | 5 | 6.6 |

| HIV-associated encephalopathy | 1 | 1.3 |

| Cytomegalovirus disease not affecting the liver, spleen or nodules | 1 | 1.3 |

| Herpes simplex: chronic ulcers (duration of >1 month); or bronchitis, pneumonitis or oesophagitis | 5 | 6.6 |

| Recurrent septicaemia due to Salmonella | 0 | |

| Histoplasmosis (disseminated or extrapulmonary) | 0 | |

| Isosporiasis (chronic intestinal; duration of >1 month) | 0 | |

| Progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy | 15 | 19.7 |

| Immunoblastic lymphoma | 3 | 4 |

| Primary cerebral lymphoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| Burkitt lymphoma | 0 | |

| Mycobacterium avium complex or Mycobacterium kansasii (disseminated or extrapulmonary) | 7 | 9.2 |

| Mycobacterium, other species or unidentified species (disseminated or extrapulmonary) | 5 | 6.6 |

| Pneumonia (recurrent) | 1 | 1.3 |

| Pneumonia due to Pneumocystis jirovecii | 3 | 4 |

| Cytomegalovirus retinitis (with loss of vision) | 14 | 18.4 |

| Kaposi sarcoma | 1 | 1.3 |

| HIV wasting syndrome | 0 | |

| Cerebral toxoplasmosis | 0 | |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis (extrapulmonary or pulmonary) | 0 | |

| Visceral leishmaniasis (kala-azar) | 1 | 1.3 |

| Not available | 7 | 9.2 |

Demographic differences and differences at diagnosis between patients with related prior visits (HIV-associated disease and/or HIV indicator condition) and patients without such visits.

| Variable | Patients with visits related to HIV infection (n = 159) | Patients with visits for other reasons (n = 193) | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean ± SD) | 37.9 ± 10.9 | 37.2 ± 12.6 | 0.608 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 145 (91.2%) | 154 (79.8%) | 0.003 |

| Nationality | |||

| Spanish | 54 (34%) | 70 (36.3%) | 0.652 |

| Route of transmission | |||

| Sexual | 143 (94.1%) | 179 (95.7%) | 0.491 |

| CDC clinical stage at diagnosis | |||

| A | 105 (70.9%) | 140 (76.9%) | 0.123 |

| B | 15 (10.1%) | 22 (11.0%) | |

| C | 28 (18.9%) | 28 (18.9%) | |

| CD4 count at diagnosis, median (IQR) | 386 (191–593) | 389 (214–591) | 0.640 |

| Viral load at diagnosis, median (IQR) | 83,251 (2,164–365,738) | 54,000 (7,000–254,486) | 0.459 |

| Viral load at diagnosis (log base 10), median (IQR) | 4.9 (3.3–5.6) | 4.8 (3.9–5.4) | 0.927 |

IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation.

It should be noted that a test to detect HIV infection was ordered in the visit in only 25 of 145 visits by patients with high-risk practices. Furthermore, HIV serology was not ordered in 17 of the 39 visits in which post-exposure prophylaxis was requested.

In patients with a prior visit to the accident and emergency department, the mean time from that visit to diagnosis was 580 (SD 647) days, 560 (SD 614) days in patients seen for HIV-associated diseases and 570 (SD 659) days in those evaluated for HIV indicator conditions. The median time from the first visit due to conditions with a high prevalence of HIV infection to diagnosis was 323 days (IQR 9–1,057).

DiscussionOf all patients diagnosed with HIV infection in 2019 at participating hospitals in our study, 16% had visited a HAED in the past five years for a reason or with a diagnosis associated with a prevalence of HIV infection exceeding 0.1%, and had not undergone a test to detect HIV infection. These patients could have benefited from an earlier diagnosis.

Failure to order serology for this infection during care in HAEDs, or make a specific referral to other levels of care for conditions with a high prevalence, caused a diagnostic delay of a median of 323 days. This means that half of patients were diagnosed almost a year later and 25% were diagnosed almost three years later. This could lead to the infection spreading even more, with patients unaware that they are HIV carriers.

Various studies have highlighted the efficiency of universal screening in Spanish HAEDs for HIV diagnosis, which is considered cost-effective when the prevalence is >0.1%14–16. However, this strategy carries logistical difficulties inherent to the procedure, as more than 23 million visits are made to accident and emergency departments every year. Recently, the Infectious Diseases in Emergency Medicine Working Group of the SEMES proposed a strategy advocating for non-emergency serology testing in patients with a limited number of conditions with high prevalences of HIV infection, which account for frequent visits to HAEDs — sexually transmitted infections, chemsex, mononucleosis-like syndrome, herpes zoster and community-acquired pneumonia — as well as patients who request post-exposure prophylaxis against HIV. In our cohort, this strategy covered 88.8% of HIV-associated diseases seen during the study period at HAEDs and 80.5% of all HIV-associated diseases and HIV indicator conditions. This bolsters the recent recommendations of the working group with the hope that, following their implementation, their efficacy may be measured in further research on the decrease in the number of missed opportunities in accident and emergency departments17,18.

The overall cohort population had certain demographic, clinical and immunological characteristics similar to those in other series of individuals diagnosed with HIV infection at present19–22. The prototypical cohort member would be a man around 36 years of age with public healthcare coverage who acquired the infection sexually. At the time of diagnosis, he would be in stage A, have a CD4 count around 400 CD4/mm3 and not have any AIDS-defining illness.

The study showed that nearly half of patients diagnosed with HIV in 2019 made at least one visit to a HAED in the past five years, with a median of two visits per patient. These people were more likely to experience an AIDS-defining illness or be in a more advanced CDC stage, and 40% had a CD4 count <350 cells/mm3 at the time of diagnosis. A CD4 count below 350 cells/mm3 at diagnosis defines late diagnosis with HIV infection23. This high proportion was similar to other current studies, and unfortunately, previous ones24–26, with no appreciable decrease therein in recent years.

In our study, two factors, high-risk sexual behaviour and requests for post-exposure prophylaxis, in which serology testing to detect HIV infection should be ordered in most cases, either in the accident and emergency department or at another level of care to which the patient might be referred in the same visit, were associated with a high number of missed opportunities. This could be due to the limitations inherent to retrospective studies with failures in information recovery, but also poor compliance with clinical guidelines and other recommendations in these two situations.

Retrospective studies are vulnerable to information recall bias and have less control over the variables analysed. They are highly dependent on the quality and reliability of the information collected in a clinical versus a research setting27. Despite these limitations inherent to its design, we believe that the study contributes high-value data towards understanding missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis in HAEDs with a view to developing strategies to improve healthcare quality.

In conclusion, 16% of patients diagnosed with HIV exhibited missed opportunities in the five years prior to diagnosis. Furthermore, one out of every four could have been diagnosed three years earlier, which might have resulted in prevention of HIV transmission and decreased odds of late diagnosis. These data reveal the need to implement an effective strategy that would enable early detection of HIV infection in HAEDs, be it through testing in situ, delayed testing of samples taken in accident and emergency departments or specific referral to other levels of care.

Conflicts of interestThe authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Alberto Pizarro Portillo, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital de la Princesa [La Princesa Hospital], Madrid, Spain.

Maite Maza Vera, Accident and Emergency Department, Complejo Hospitalario de Vigo [Vigo Hospital Complex], Vigo, Pontevedra, Spain.

Ferran Llopis Roca, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Universitari de Bellvitge [Bellvitge University Hospital], L'Hospitalet de Llobregat, Barcelona, Spain.

Manuel Gil Mosquera, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital 12 de Octubre [12 de Octubre Hospital], Madrid, Spain.

Oriol Yuguero Torres, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital de Lleida [Lleida Hospital], Lleida, Spain.

Eva Quero-Motto, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Clínico Universitario Virgen de la Arrixaca [Virgen de la Arrixaca University Clinical Hospital]/Instituto Murciano de Investigación Biosanitaria [Biomedical Research Institute of Murcia] (IMIB), Murcia, Spain.

Elena Sánchez Maganto, Accident and Emergency Department, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Toledo [Toledo University Hospital Complex], Toledo, Spain.

Marta Álvarez Alonso, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital de Fuenlabrada [Fuenlabrada Hospital], Fuenlabrada, Madrid, Spain.

Carlos del Pozo Vegas, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Clínico Universitario de Valladolid [Valladolid University Clinical Hospital], Valladolid, Spain.

Pascual Piñera Salmerón, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Reina Sofía de Murcia [Queen Sofía Hospital of Murcia], Murcia, Spain.

María Velasco Arribas, Internal Medicine/Infectious Disease Unit, Hospital Universitario Fundación Alcorcón [Alcorcón Foundation University Hospital], Alcorcón, Madrid, Spain.

Raúl López Izquierdo, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario Pío del Rio Hortega [Pío del Rio Hortega University Hospital], Valladolid, Spain.

Carmen Peñalver Barrios, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital General de Segovia [Segovia General Hospital], Segovia, Spain.

Belén Rodríguez Miranda, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Universitario Rey Juan Carlos [King Juan Carlos University Hospital], Móstoles, Madrid, Spain.

Ramón Perales Pardo, Accident and Emergency Department, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete [Albacete University Hospital Complex], Albacete, Spain.

Beatriz Valle Borrego, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Severo Ochoa [Severo Ochoa Hospital], Leganés, Madrid, Spain.

Félix González Martínez, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Virgen de la Luz [Virgen de la Luz Hospital], Cuenca, Spain.

Àngels Gispert Ametller, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Universitari de Girona Doctor Josep Trueta [Doctor Josep Trueta University Hospital of Girona], Girona, Spain.

Marta Iglesias Vela, Accident and Emergency Department, Complejo Asistencial Universitario de León [León University Healthcare Complex] (CAULE), León, Spain.

Elizabeth Ortiz García, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital de Santa Barbara [Santa Barbara Hospital], Soria, Spain.

Carmen Boque Oliva, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Joan XXIII [Joan XXIII Hospital], Tarragona, Spain.

Sara Gayoso Martín, Accident and Emergency Department, Hospital Comarcal El Escorial [El Escorial Regional Hospital], San Lorenzo de El Escorial, Madrid, Spain.

A list of the members of the Infectious Diseases in Emergency Medicine Working Group of the Sociedad Española de Medicina de Urgencias y Emergencias [Spanish Society of Emergency Medicine] (INFURG-SEMES) appears in Annex 1.