In response to the need for new antibiotics, the late 1940s witnessed the development of the first tetracyclines obtained from different species of Streptomyces spp.

As the intensive use of tetracyclines in both humans and the veterinary industry led to the emergence of bacterial resistance, new semi-synthetic tetracyclines were developed, particularly tigecycline1. The relatively limited antimicrobial spectrum of the classic tetracyclines, the fact that they cannot be used in children or during pregnancy or lactation, and the emergence of new, more effective components in other families of antibiotics, all prompted a gradual decline in the use of tetracyclines in humans2. Nevertheless, certain tetracyclines are still used in routine clinical practice, mainly due to their broad spectrum of action, with activity against multiresistant microorganisms, in addition to being a therapeutic alternative for patients with allergies to other antibiotics.

We present the case of a 73-year-old female patient, allergic to penicillins, with a medical history of hypertension, dyslipidaemia and hypothyroidism.

The patient came to the Accident and Emergency Department with poor general condition and a one-month history of a painful neck tumour. In the initial assessment, she was conscious and orientated, with adequate distal perfusion and mild tachypnoea. Her baseline oxygen saturation was 95%, mean arterial pressure 50mmHg, with sinus tachycardia of 100bpm and a temperature of 37.8°C. Blood results showed acute kidney failure, with creatinine 2mg/dl, urea 134mg/dl, glomerular filtration rate 24ml/min/1.73m2, procalcitonin 2ng/ml and leucocytes 9,300/mm3.

The computed tomography of the neck revealed extensive bilateral inflammatory involvement on the anterior neck, with multiloculated abscess-like fluid collections. Urgent surgery was performed, with drainage of the purulent collections of fluid and debridement of adjacent structures. The patient was transferred to the Intensive Care Unit, sedated with analgesia and connected to mechanical ventilation. She was given empirical antibiotic therapy at an initial dose of 100mg, followed by 50mg every 12h and clindamycin (600mg every 8h). Streptococcus anginosus was isolated from an intraoperative sample of the neck abscess.

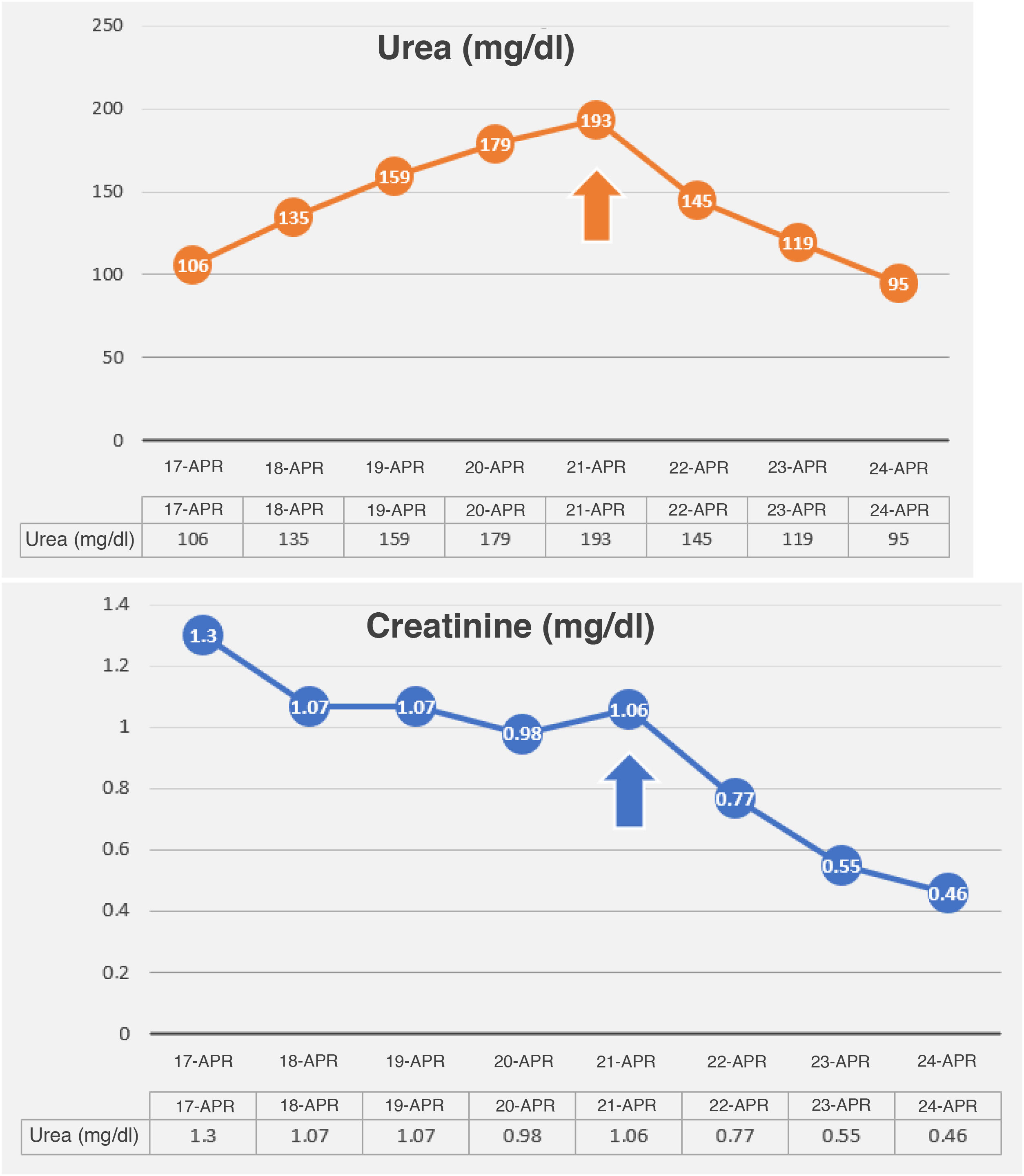

Over the following days, the patient’s infectious condition was seen to improve. However, blood tests showed a persistent metabolic acidosis despite adequate haemodynamic resuscitation, with the need for low-dose noradrenaline for a mean arterial pressure of 65mmHg. She presented dissociation of the urea/creatinine ratio, with elevation of urea levels to a maximum peak of 193mg/dl, with creatinine 1.06mg/dl and hyperphosphataemia. Adequate diuresis was maintained without the need for diuretics; her liver profile was within the normal range. However, severe myopathy delayed the withdrawal of the mechanical ventilation despite adequate oxygenation.

Following an exhaustive study of the case and a literature review, this analytical and clinical finding was interpreted as an adverse effect of tigecycline. After 96h, the tetracycline was withdrawn from the treatment and replaced with levofloxacin. 24h after the withdrawal, the patient’s urea levels had fallen to 145mg/dl, with creatinine 0.77mg/dl and improvement of the metabolic acidosis. The evolution in the analytical data are shown in Fig. 1.

The Karch and Lasagna algorithm was applied to confirm the causal relationship of the adverse effect with tigecycline and a total score of 8 points was obtained, demonstrating a definite relationship between both events3 (Table 1).

Application of the modified Karch and Lasagna algorithm.

| Assessment criterion | Classification | Description | Score |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time sequence | Consistent | The adverse event described (hyperazotaemia) appears during or after the administration of the medicinal product (tigecycline) and is consistent with the drug’s mechanism of action or with the idiosyncratic process | +2 |

| Previous knowledge | Well-known ADR | Causal relationship listed in the summary of product characteristics | +2 |

| Effect of withdrawal of suspected medicinal product | Improvement of ADR | The event improves on withdrawal of the medicinal product, regardless of the treatment received | +2 |

| Effect of re-exposure to the suspected medicinal product | There is no re-exposure | There was no re-exposure | 0 |

| Existence of alternative causes | There is information that rules out an alternative explanation | There is enough information not to suspect an alternative cause. There is no plausible association between the underlying disease or other medication taken simultaneously with the causal relationship studied | +1 |

| Contributing factors that support the assessment of causality | None or unknown | Factors in the suspected medicinal product which may have contributed to the occurrence of the adverse reaction | 0 |

| Complementary explorations | There are complementary explorations | Serial analytical data obtained | +1 |

We should also point out that according to the literature, none of the other treatments given to the patient as of her admission to the intensive care unit (remifentanil, propofol, dexmedetomidine, total parenteral nutrition, noradrenaline, vitamin K, omeprazole, paracetamol and clindamycin) has any obvious relationship with the increase in plasma urea.

Hyerazotaemia can have an extrarenal cause, due to increased production of urea secondary to high-protein diets, gastrointestinal bleeding, situations that increase protein catabolism (sepsis, multiple trauma, stress, etc) or drugs that inhibit anabolic metabolism (tetracyclines and corticosteroids). A renal cause for the increase in plasma urea is also possible, considering three different types: (a) prerenal due to absolute hypovolaemia (gastrointestinal, renal and skin losses and third space sequestration) or relative hypovolaemia (hepatorenal syndrome, heart failure, liver cirrhosis, nephrotic syndrome, consumption of NSAID or ACE inhibitors); (b) of parenchymal origin, due to acute tubular necrosis, glomerulopathy, tubulointerstitial nephropathy (aminoglycosides, vancomycin, amphotericin B, cephalosporins, anaesthetics, ciclosporin, tacrolimus, radiological contrast agents, pigments [myoglobin, haemoglobin], metals and systemic diseases [sarcoidosis, tuberculosis, Sjögren’s syndrome, multiple myeloma]); and (c) of post-renal aetiology, due to decreased glomerular filtration resulting from obstruction to urine flow in any part of the urinary tract, intrinsic obstruction (clots, crystals, casts) or extrinsic obstruction (prostatic disease, retroperitoneal fibrosis or neoplasms)4.

Reviewing the published literature, we found several authors who, as far back as the 20th century5–10, detected a clinical picture of metabolic acidosis, hyperazotaemia and hyperphosphataemia in patients on treatment with tetracyclines. The withdrawal of the antibiotic from the treatment reversed the laboratory abnormalities in most cases, regardless of the patient’s renal function prior to the acute disease. These authors associated this adverse event with the antianabolic effect of tetracyclines.

According to the summary of product characteristics issued by the Spanish Agency of Medicines and Medical Devices, unlike other tetracyclines, tigecycline does not require dose adjustment to renal function. We believe that the publication of this case is important due to the high degree of clinical suspicion required for diagnosis, as well as the need to investigate the underlying pathophysiological mechanism and to reassess whether this antibiotic requires stricter control in patients with impaired renal function. These factors are particularly important since, while stigmatised in the past, tetracyclines continue to be a valuable treatment option in our day-to-day practice.

Please cite this article as: Esteban-Molina A, Royo-Álvarez M, Araujo-Aguilar P, Bernal-Matilla CI. Azoemia inducida por tigeciclina. Enferm Infecc Microbiol Clin. 2022;40:461–463.