Infectious pathologies can benefit from the application of Telemedicine (TM). This study provides a description of the infectious pathology treated by the Telemedicine Service of the Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla (STM-HCDGU).

MethodsAnalysis of the e-consultations made by members of the Armed Forces (FA) of Spain displaced to the area of operations (ZO) in the period between 01/1/2015 and 31/12/2018 who developed infectious symptoms.

Results127 infectious diseases were diagnosed, the most frequent being those of respiratory etiology and later malaria. Geographically Africa and embarked contingents were the most significant. It was necessary to evacuate 18 patients to the HCDGU, being the diagnosis of malaria the most frequent reason for evacuation, cause of the only fatal case.

Conclusionsinfectious diseases benefit from the application of TM, being an important tool for the diagnosis and treatment of these, constituting an opportunity to expand to other displaced or remote populations.

Las patologías infecciosas pueden beneficiarse de la aplicación de la Telemedicina (TM). Este estudio realiza una descripción de la patología infecciosa atendida por el Servicio de Telemedicina del Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla (STM-HCDGU).

MétodosAnálisis de las e-consultas realizadas por miembros de las Fuerzas Armadas (FA) de España desplazados a zona de operaciones (ZO) en el periodo comprendido entre 01/1/2015 y 31/12/2018 que desarrollaron sintomatología infecciosa.

ResultadosSe diagnosticaron 127 enfermedades infecciosas, siendo las más frecuentes las de etiología respiratoria y posteriormente la malaria. Geográficamente África y contingentes embarcados fueron los más significados. Fue necesario evacuar 18 pacientes al HCDGU siendo el diagnóstico de malaria el motivo de evacuación más frecuente, causa del único caso mortal.

Conclusioneslas enfermedades infecciosas se benefician de la aplicación de la TM, siendo una herramienta importante para el diagnóstico y tratamiento de estas, constituyendo una oportunidad para ampliar a otras poblaciones desplazadas o remotas.

Telemedicine (TM) is a term coined in the 1970s and whose literal meaning is "healing at a distance".1 The World Health Organization defines it as "the delivery of healthcare services, where distance is a critical factor, by all healthcare professionals using information and communication technologies for the exchange of valid information for diagnosis, treatment and prevention of disease and injuries, research and evaluation, and for the continuing education of healthcare providers, all in the interests of advancing the health of individuals and their communities".2

Infectious diseases can benefit from the application of TM.3,4 In two studies, Eron et al.5 and Assimacopoulos et al.6 obtained significant results that demonstrated how the application of TM facilitated satisfactory clinical results, faster recoveries, presenting a shorter duration of antibiotic therapy and hospitalisation, and reducing the number of transfers due to worsening than in comparable hospitalised patients.

In the military field, TM is a very useful tool. The US Army has documented that casualties due to infectious diseases have a specific weight among the reasons for casualties in the area of operations (AO).7

The Telemedicine Service of the Hospital Central de la Defensa Gómez Ulla [Gómez Ulla Central Military Hospital] (TMS-HCDGU) was the first in Spain and was inaugurated in 1996, with the name, Telemedicine Unit.8

The objective of this study is to describe and detail the aetiology of infectious diseases treated by the TMS-HCDGU.

Materials and methodsTarget populationMembers of the Spanish Armed Forces (AF) over 18 years of age relocated to the AO between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2018.

Inclusion criteriaMembers of the AF with infectious symptoms and who request e-consultation with the TMS-HCDGU.

Exclusion criteriaReason for consultation whose final diagnosis is not of infectious aetiology.

Telemedicine service logisticsThe HCDGU is the upper echelon of health support for military personnel, guaranteeing uninterrupted coverage throughout the year. The TMS is integrated within it, providing assistance and subsequent confirmation or modification of diagnoses and treatments of the diseases consulted for.

E-consultations are carried out by e-mail, video conferences/video calls via satellite. The TMS-HCDGU refers the consultation to the doctor whose specialisation is related to the suspected diagnosis. After evaluating the clinical history issued, the specialist can request more information or make a diagnosis, prescribe treatment, follow the patient's evolution and, where necessary, issue a recommendation for evacuation to national territory.

Variables collectedThe variables collected included epidemiological (age, sex, date of e-consultation), geomilitary (type of base, land/naval location) and medical data (history, diagnosis of the process, treatment, evacuation).

The data was analysed with the SPSS program (IBM Statistics V25.0), presenting the frequencies and percentages of the qualitative variables with their 95% confidence interval, and the means and confidence interval of the quantitative variables.

PermissionsThe study was authorised by the Mando de Operaciones [Operations Command] of the Estado Mayor de la Defensa [Chiefs of Defence], Ministry of Defence Health Information System, as well as by the Teaching Commission and the Medicines Research Ethics Committee of the HCDGU.

ResultsThe sample consisted of 644 records, with a total of 127 e-consultations in relation to infectious disease after applying the exclusion criteria, 19.7% (95% CI, 16.7–23). The gender distribution was 120 men and 7 women, with a mean age (95% CI) of 33.31 years (31.6–35).

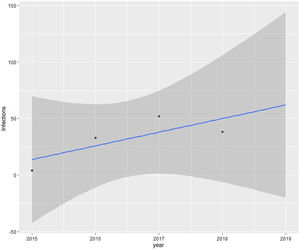

Based on the annual distribution of e-consultations, an increase in these was observed, with the maximum in 2017 being 52 (41%). The analysis shows a growing trend of e-consultations for infectious diseases (Fig. 1).

E-consultation requests to the TMS-HCDGU were most commonly from naval ships. Next were contingents based in Africa, with these two categories making up 85% of the total. There were no e-consultations from Latin America, since there is only one cooperation mission, and none of the diseases consulted were of infectious aetiology. As an in-demand specialisation Internal Medicine stands out primarily with 84 cases, 61% of the total.

Acute pharyngotonsillitis was the disease most frequently consulted for, followed by malaria. Combining upper and lower respiratory tract diseases, a total of 39 (30.7%) e-consultations were obtained (Table 1).

Description of the infectious diseases treated.

| Diagnosis | No. of cases | Evacuations | Mortality | Africa | Europe | Naval | Middle East |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acute pharyngotonsillitis | 26 (20.47%) | – | – | 9 | 2 | 15 | – |

| Malaria | 14 (11.02%) | 7 (50%) | 1 (7.14%) | 5 | – | 9 | – |

| Respiratory infection | 13 (10.23%) | 4 (30.76%) | – | 8 | 1 | 4 | – |

| Otitis | 9 (7.08%) | 1 (11.11%) | – | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Urine infection | 9 (7.08%) | – | – | 1 | 2 | 6 | – |

| Traveller's diarrhoea | 8 (6.29%) | 1 (12.5%) | – | 5 | – | 2 | 1 |

| Lower limb cellulitis | 8 (6.29%) | – | – | 3 | 1 | 3 | 1 |

| Epididymitis | 7 (5.51%) | 1 (14.28%) | – | 2 | – | 3 | 2 |

| Viral infection* | 6 (4.72%) | 2 (33.33%) | – | – | – | 3 | 3 |

| Oral cavity infection | 4 (3.14%) | – | – | – | – | 4 | – |

| Other (maximum 2 cases) | 23 (18.11%) | 2 (8.69%) | – | 10 | – | 10 | 3 |

| Total | 127 (100%) | 18 (14.17%) | 1 (7.14%) | 47 (37.01%) | 8 (6.30%) | 61 (48.03%) | 11 (8.66%) |

A total of 18 cases (14.27%) were evacuated to the HCDGU. 50% of malaria cases were evacuated, which is the most common infectious disease requiring evacuation. Viral infections were evacuated in a proportion of 33% (mononucleosis and dog-bite rabies). The cases evacuated belonging to the category of “other” were septic arthritis and meningitis.

The patient who died of malaria had a correct diagnosis, but the evolution was not satisfactory due to complications related to the disease itself.

DiscussionOur study confirms that infectious diseases are among the most common medical conditions experienced by the AFs while serving missions outside their home countries.9 The specific weight of casualties or unavailability to perform assigned tasks (estimated by consensus to be 3 days) due to disease of infectious aetiology is important.10 Diagnosing effectively allows to reduce casualties and carry out a preventive health policy for future contingents.

Lappan11 classified the reasons for e-consultation from 2004 to the first quarter of 2018. Of 14,439 e-consultations, 1,060 were of infectious aetiology, which represents 7.3% in 13 years. The percentage difference between our data and that collected by Lappan can be explained by a different geographical distribution of the contingents between both studies. Despite the limitations of our study, with fewer e-consultations and a shorter study period, many infectious diseases were observed, constituting an advantage that enabled us to identify, classify and understand which entities are more prevalent in the scenario handled by Spain. The growth trend at the time of consulting may be related to the awareness of the importance of consulting for symptoms of infectious aetiology, since its specific weight, in the case of developing disease, is important and alters the normal functioning of the mission.

Physicians specialising in Internal Medicine were the highest in demand. This can be explained by the fact that this specialisation brings together professionals dedicated to infectious diseases and frequently consulted for this purpose in the hospital setting.12

Those in Africa and those aboard ships accounted for 85% of e-consultations. In Africa, the tropical climate conditions added to the presence of vectors explain these findings, which are complemented by the diagnoses obtained from naval ships, which are mainly deployed in tropical regions. This provides information on how the coexistence of a large number of people in a small space can be a breeding ground for infectious diseases.

Malaria was diagnosed on a ship in 9 of 14 cases. The primary infection may be related to a situation where the ship is moored, but the symptoms that led to diagnosis occurred at sea and thus we see the importance of having access to infectious disease specialists, for better treatment and evolution of a disease that can be life-threatening, demonstrated by the only case of mortality in the sample. Diagnosis is carried out by rapid diagnostic tests in the field. Both the thick smear and other microbiological diagnoses that are necessary to identify the causative pathogen are carried out in support hospitals to which the samples are sent.

The role of TM as a tool to discern the need or not for evacuation has been shown to be vital. Hwang et al.13 conducted a review of dermatology e-consultations (2004–2012). They found that TM is an effective tool to avoid unnecessary medical evacuations, and to support or decide on a series of necessary evacuations that would otherwise have been delayed.

The current epidemiological situation highlights the importance of the application of TM,14 and it is necessary to direct this tool to more diverse groups (not only military), such as populations with limited access to a tertiary hospital. With the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, it is essential to provide patients with adequate clinical guidance and regulate hospital healthcare flows, so that health systems can withstand the healthcare pressure of the times we live in.15

Currently, this study, the first of a displaced Spanish population, is a touchstone for promoting the application of TM in infectious diseases in the coming years.

ConclusionsOur paper highlights that infectious diseases benefit from the application of TM, especially in the military field, as it is an important tool for their diagnosis and treatment. This is the first study of these characteristics in Spain, and opens the way for more effective prevention policies. It is a valid model for developing a public health programme for access to remote populations (non-military displaced persons, for example volunteering and international cooperation).

Conflicts of interestNone of the authors have any conflicts of interest.